2.3: Derivatives of Rational Functions

- Page ID

- 155802

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A term of the form \[a_{1}x + a_{0} \nonumber\]where \(a_{1}\), \(a_{0}\) are real numbers, is called a linear term in \(x\); if \(a_{1} \neq 0\), it is also called a polynomial of degree one in \(x\). A term of the form \[a_{2} x^{2} + a_{1}x + a_{0}, \quad a_{2} \neq 0 \nonumber\]is called a polynomial of degree two in \(x\), and, in general, a term of the form \[a_{n}x^{n} + a_{n-1}x^{n-1} + \cdots + a_{1}x + a_{0}, \quad a_{n} \neq 0 \nonumber\]is called a polynomial of degree \(n\) in \(x\).

A rational term in \(x\) is any term which is built up from the variable \(x\) and real numbers using the operations of addition, multiplication, subtraction, and division. For example, every polynomial is a rational term and so are the terms \[\frac{\left(3x^{2} - 5\right) (x+2)^{3}}{5x - 11}, \quad \frac{(1 + 1/x)^{9}}{x^{3} + 1/(2-x)}. \nonumber\]

A linear function, polynomial function, or rational function is a function which is given by a linear term, polynomial, or rational term, respectively. In this section we

shall establish a set of rules which enable us to quickly differentiate any rational function. The rules will also be useful later on in differentiating other functions.

The derivative of a linear function is equal to the coefficient of \(x\). That is, \[\frac{d(bx+c)}{dx} = b, \quad d(bx+c) = b \ dx. \nonumber\]

Proof

Let \(y = bx + c\), and let \(\Delta x \neq 0\) be infinitesimal. Then \[\begin{align*} y + \Delta y &= b(x + \Delta x) + c, \\ \Delta y &= (b(x + \Delta x) + c) - (bx + c) = \Delta x, \\ \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} &= \frac{b \Delta x}{\Delta x} = b. \end{align*}\]

Therefore \[\frac{dy}{dx} = st(b) = b. \nonumber\]

Multiplying through by \(dx\), we obtain at once \[dy = b \ dx \nonumber.\]

If in Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\) we put \(b = 1\), \(c = 0\), we see that the derivative of the identity function \(f(x) = x\) is \(f'(x) = 1\); i.e., \[\frac{dx}{dx} = 1; \quad dx = dx. \nonumber\]

On the other hand, if we put \(b = 0\) in Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\) then the term \(bx + c\) is just the constant \(c\), and we find that the derivative of the constant function \(f(x) = c\) is \(f'(x) = 0\); i.e., \[\frac{dc}{dx} = 0, \quad dc = 0. \nonumber\]

Suppose \(u\) and \(v\) depend on the independent variable \(x\). Thenfor any value of \(x\) where \(du/dx\) and \(dv/dx\) exist, \[\frac{d(u+v)}{dx} = \frac{du}{dx} + \frac{dv}{dx}, \quad d(u+v) = du + dv \nonumber\]

Proof

Let \(y = u + v\), and let \(\Delta x \neq 0\) be infinitesimal. Then \[\begin{align*} y + \Delta y &= (u + \Delta u) + (v + \Delta v), \\ \Delta y &= [(u + \Delta u) + (v + \Delta v)] - [u + v] = \Delta u + \Delta v, \\ \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \frac{\Delta u + \Delta v}{\Delta x} &= \frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x} + \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}. \end{align*}\]

Taking standard parts, \[st \left(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\right) = st \left(\frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x} + \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}\right) + st \left(\frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x}\right) + st \left(\frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}\right). \nonumber\]

Thus \[\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{du}{dx} + \frac{dv}{dx}. \nonumber\]

By using the Sum Rule \(n - 1\) times, we see that \[\frac{d \left(u_{1} + \cdots + u_{n}\right)}{dx} = \frac{du_{1}}{dx} + \cdots + \frac{du_{n}}{dx}, \text{ or } d \left(u_{1} + \cdots + u_{n}\right) = du_{1} + \cdots + du_{n}. \nonumber\]

Suppose \(u\) depends on \(x\), and \(c\) is a real number. Then for any value of \(x\) where \(du/dx\) exists, \[\frac{d(cu)}{dx} = c \frac{du}{dx}, \quad d(cu) = c \ du. \nonumber\]

Proof

Let \(y = cu\), and let \(\Delta x \neq 0\) be infinitesimal. Then \[\begin{align*} y + \Delta y &= c(u + \Delta u), \\ \Delta y &= c(u + \Delta u) - cu = c \Delta u, \\ \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} &= \frac{c \Delta u}{\Delta x} = c \frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x}. \end{align*}\]

Taking standard parts, \[st \left(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\right) = st \left(c \frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x}\right) = c \ st \left(\frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x}\right). \nonumber\]

whence \[\frac{dy}{dx} = c \frac{du}{dx}. \nonumber\]

The Constant Rule shows that in computing derivatives, a constant factor may be moved "outside" the derivative. It can only be used when \(c\) is a constant. For products of two functions of \(x\), we have:

Suppose \(u\) and \(v\) depend on \(x\). Then for any value of \(x\) where \(du/dx\) and \(dv/dx\) exist, \[\frac{d(uv)}{dx} = u \frac{dv}{dx} + v \frac{du}{dx}, \quad d(uv) = u \ dv + v \ du. \nonumber\]

Proof

Let \(y = uv\), and let \(\Delta x \neq 0\) be infinitesimal. \[\begin{align*} y + \Delta y &= (u + \Delta u)(v + \Delta v), \\ \Delta y &= (u + \Delta u)(v + \Delta v) - uv = u \Delta v + v \Delta u + \Delta u \Delta v, \\ \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} &= \frac{u \Delta v + v \Delta u + \Delta u \Delta v}{\Delta x} = u \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x} + v \frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x} + \Delta u \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}. \end{align*}\]

\(\Delta u\) is infinitesimal by the Increment Theorem, whence \[\begin{align*} st \left(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\right) &= st \left(u \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x} + v \frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x} + \Delta u \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}\right) \\ &= u \cdot st \left(\frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}\right) + v \cdot st \left(\frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x}\right) + 0 \cdot st \left(\frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}\right). \end{align*}\]

So \[\frac{dy}{dx} = u \frac{dv}{dx} + v \frac{du}{dx}. \nonumber\]

The Constant Rule is really the special case of the Product Rule where \(v\) is a constant function of \(x\), \(v = c\). To check this we let \(v\) be the constant \(c\) and see what the Product Rule gives us: \[\frac{d (u \cdot c)}{dx} = u \frac{dc}{dx} + c \frac{du}{dx} = u \cdot 0 + c \frac{du}{dx} = c \frac{du}{dx}. \nonumber\]This is the Constant Rule.

The Product Rule can also be used to find the derivative of a power of \(u\).

Let \(u\) depend on \(x\) and let \(n\) be a positive integer. For any value of \(x\) where \(du/dx\) exists, \[\frac{d \left(u^{n}\right)}{dx} = nu^{n-1} \frac{du}{dx}, \quad d \left(u^{n}\right) = nu^{n-1} \ du. \nonumber\]

Proof

To see what is going on we first prove the Power Rule for \(n = 1, 2, 3, 4\).

\(n = 1:\) We have \(u^{n} = u\) and \(u^{0} = 1\), whence \[\frac{d \left(u^{n}\right)}{dx} = \frac{du}{dx} = 1 \cdot u^{0} \cdot \frac{du}{dx}. \nonumber\]

\(n = 2:\) We use the Product Rule, \[\frac{d \left(u^{2}\right)}{dx} = \frac{d (u \cdot u)}{dx} = u \frac{du}{dx} + u \frac{du}{dx} = 2 \cdot u^{1} \cdot \frac{du}{dx}. \nonumber\]

\(n = 3:\) We write \(u^{3} = u \cdot u^{2}\), use the Product Rule again, and then use the result for \(n = 2\). \[\begin{align*} \frac{d \left(u^{3}\right)}{dx} &= u \frac{d \left(u \cdot u^{2}\right)}{dx} + u^{2} \frac{du}{dx} \\[4pt] &= u \cdot 2u \frac{du}{dx} + u^{2} \frac{du}{dx} = 3u^{2} \frac{du}{dx} \end{align*}\]

\(n = 4:\) Using the Product Rule and then the result for \(n = 3\), \[\begin{align*} \frac{d \left(u^{4}\right)}{dx} &= \frac{d \left(u \cdot u^{3}\right)}{dx} = u \frac{d \left(u^{3}\right)}{dx} + u^{3} \frac{du}{dx} \\[4pt] &= u \cdot 3u^{2} \frac{du}{dx} + u^{3} \frac{du}{dx} = 4u^{3} \frac{du}{dx}. \end{align*}\]

We can continue this process indefinitely and prove the theorem for every positive integer \(n\). To see this, assume that we have proved the theorem form. That is, assume that \[\frac{d \left(u^{m}\right)}{dx} = m u^{m-1} \frac{du}{dx}.\]

We then show that it is also true for \(m + 1\). Using the Product Rule and Equation \((\PageIndex{1})\), \[\begin{align*} \frac{d \left(u^{m+1}\right)}{dx} &= \frac{d \left(u \cdot u^{m}\right)}{dx} = u \frac{d \left(u^{m}\right)}{dx} + u^{m} \frac{du}{dx} \\ &= u \cdot m^{m-1} \frac{du}{dx} + u^{m} \frac{du}{dx} = (m+1) u^{m} \frac{du}{dx}. \end{align*}\]

Thus \[\frac{d \left(u^{m+1}\right)}{dx} = (m+1) u^{m} \frac{du}{dx}. \nonumber\]

This shows that the theorem holds for \(m + 1\).

We have shown the theorem is true for 1, 2, 3, 4. Set \(m = 4\); then the theorem holds for \(m + 1 = 5\). Set \(m = 5\); then it holds for \(m + 1 = 6\). And so on. Hence the theorem is true for all positive integers \(n\).

In the proof of the Power Rule, we used the following principle:

Suppose a statement \(P(n)\) about an arbitrary integer \(n\) is true when \(n = 1\). Suppose further that for any positive integer \(m\) such that \(P(m)\) is true, \(P(m + 1)\) is also true. Then the statement \(P(n)\) is true of every positive integer \(n\).

In the previous proof, \(P(n)\) was the Power Rule, \[\frac{d \left(u^{n}\right)}{dx} = n u^{n-1} \frac{du}{dx}. \nonumber\]

The Principle of Induction can be made plausible in the following way. Let a positive integer \(n\) be given. Set \(m = 1\); since \(P(1)\) is true, \(P(2)\) is true. Now set \(m = 2\); since \(P(2)\) is true, \(P(3)\) is true. We continue reasoning in this way for \(n\) steps and conclude that \(P(n)\) is true.

The Power Rule also holds for \(n = 0\) because when \(u \neq 0\), \(u_{0} = 1\) and \(d1/dx = 0\).

Using the Sum, Constant, and Power rules, we can compute the derivative of a polynomial function very easily. We have \[\begin{align*} \frac{d \left(x^{n}\right)}{dx} &= nx^{n-1}, \\[4pt] \frac{d \left(cx^{n}\right)}{dx} &= cnx^{n-1}, \end{align*}\]

and thus \[\frac{d \left(a_{n} x^{n} + a_{n-1} x^{n-1} + \cdots + a_{1} x + a_{0}\right)}{dx} = a_{n} \cdot nx^{n-1} + a_{n-1} (n-1) x^{n-2} + \cdots + a_{1}. \nonumber\]

\[\frac{d \left(-3 x^{5}\right)}{dx} = -3 \cdot 5x^{4} = -15x^{4}. \nonumber\]

\[\frac{d \left(6x^{4} - 2x^{3} + x - 1\right)}{dx} = 24x^{3} - 6x^{2} + 1. \nonumber\]

Two useful facts can be stated as corollaries.

Corollary \(\PageIndex{5.1}\):

The derivative of a polynomial of degree \(n > 0\) is a polynomial of degree \(n - 1\). (A nonzero constant is counted as a polynomial of degree zero.)

Corollary \(\PageIndex{5.2}\):

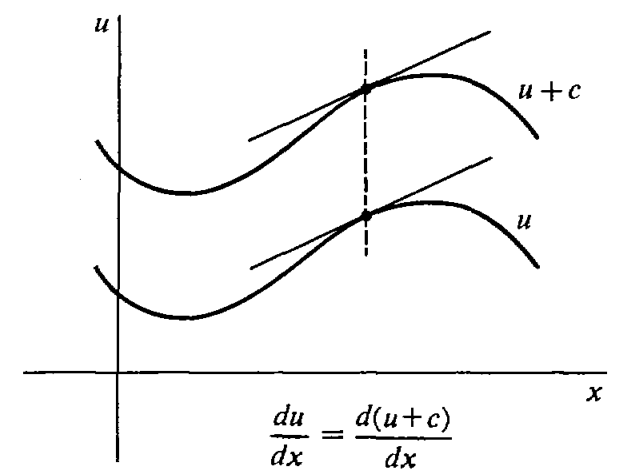

If \(u\) depends on \(x\), then \[\frac{d (u+c)}{dx} = \frac{du}{dx} \nonumber\]whenever dujdx exists. That is, adding a constant to a function does not change its derivative.

In Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) we see that the effect of adding a constant is to move the curve up or down the \(y\)-axis without changing the slope. For the last two rules in this section we need the formula for the derivative of \(1/v\).

Suppose \(v\) depends on \(x\). Then for any value of \(x\) where \(v \neq 0\) and \(dv/dx\) exists, \[\frac{d (1/v)}{dx} = -\frac{1}{v^{2}} \frac{dv}{dx}, \quad d \left(\frac{1}{v}\right) = -\frac{1}{v^{2}} dv. \nonumber\]

Proof

Let \(y = 1/v\) and let \(\Delta x \neq 0\) be infinitesimal.

\[\begin{align*} y + \Delta y &= \frac{1}{v + \Delta v}, \\ \Delta y &= \frac{1}{v + \Delta v} - \frac{1}{v}, \\ \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} &= \frac{1/(v + \Delta v) - 1/v}{\Delta x} \\ &= \frac{v - (v + \Delta v)}{\Delta x \ v (v + \Delta v)} \\ &= -\frac{1}{v (v + \Delta v)} \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}. \end{align*}\]

Taking standard parts, \[\begin{align*} st \left(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\right) &= st \left(- \frac{1}{v (v + \Delta v)} \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}\right) \\ &= st \left(- \frac{1}{v (v + \Delta v)}\right) st \left(\frac{\Delta v}{\Delta x}\right) \\ &= -\frac{1}{v^{2}} st \left(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\right). \end{align*}\]

Therefore \[\frac{dy}{dx} = -\frac{1}{v^{2}} \frac{dv}{dx}. \nonumber\]

Suppose \(u\), \(v\) depend on \(x\). Then for any value of \(x\) where \(du/dx\), \(dv/dx\) exist and \(v \neq 0\), \[\frac{d(u/v)}{dx} = \frac{v \ du/dx - u \ dv/dx}{v^{2}}, \quad d \left(\frac{u}{v}\right) = \frac{v \ du - u \ dv}{v^{2}}. \nonumber\]

Proof

We combine the Product Rule and the formula for \(d(1/v)\). Let \(y = u/v\). We write \(y\) in the form \[y = \frac{1}{v} \cdot u. \nonumber\]

Then \[\begin{align*} dy &= d \left(\frac{1}{v} u \right) = \frac{1}{v} du + u d \left(\frac{1}{v}\right) \\ &= \frac{1}{v} du + u \left(-v^{-2}\right) dv \\ &= \frac{v \ du - u \ dv}{v^{2}}. \end{align*}\].

Suppose \(u\) depends on \(x\) and \(n\) is a negative integer. Then for any value of \(x\) where \(du/dx\) exists and \(u \neq 0\), \(d \left(u^{n}\right)/dx\) exists and \[\frac{d \left(u^{n}\right)}{dx} = nu^{n-1} \frac{du}{dx}, \quad d \left(u^{n}\right) = nu^{n-1} \ du. \nonumber\]

Proof

Since \(n\) is negative, \(n = - m\) where \(m\) is positive. Let \(y = u^{n} = u^{-m}\). Then \(y = 1/u^{m}\). By the Lemma and the Power Rule,

\[\begin{align*} \frac{dy}{dx} &= -\frac{1}{\left(u^{m}\right)^{2}} \cdot \frac{d \left(u^{m}\right)}{dx} \\ &= -\frac{1}{u^{2m}} \cdot mu^{m-1} \frac{du}{dx} \\ &= (-m) u^{-2m} u^{m-1} \frac{du}{dx} \\ &= (-m) u^{-m-1} \frac{du}{dx} = nu^{n-1} \frac{du}{dx} \end{align*}\]

The Quotient Rule together with the Constant, Sum, Product, and Power Rules make it easy to differentiate any rational function.

Find \(dy\) when \[y = \frac{1}{x^{2} - 3x + 1}. \nonumber\]

Solution

Introduce the new variable \(u\) with the equation \[u = x^{2} - 3x + 1. \nonumber\]Then \(y = 1/u\), and \(du = (2x - 3) dx\), so \[dy = -\frac{1}{u^{2}} du = \frac{-(2x-3)}{\left(x^{2} - 3x + 1\right)^{2}} dx. \nonumber\]

Let \(y = \dfrac{\left(x^{4} - 2\right)^{3}}{5x - 1}\) and find \(dy\).

Solution

Let \(u = \left(x^{4} - 2\right)^{3}, \quad v = 5x - 1.\)

Then \(y = \dfrac{u}{v}, \quad dy = \dfrac{v \ du - u \ dv}{v^{2}}.\)

Also, \(\begin{align*} du &= 3 \cdot \left(x^{4} - 2\right)^{2} \dot 4x^{3} \ dx = 12 \left(x^{4} - 2\right) \cdot x^{3} \ dx, \\ dv &= 5 \ dx. \end{align*}\)

Therefore \(\begin{align*} dy &= \dfrac{(5x-1) \cdot 12 \left(x^{4} - 2\right)^{2} x^{3} \ dx - \left(x^{4} - 2\right)^{3} \cdot 5 \ dx}{(5x-1)^{2}} \\ &= \dfrac{\left(x^{4} - 2\right)^{2} \left[12 (5x-1)x^{3} - 5 \left(x^{4} - 2\right)\right]}{(5x-1)^{2}} dx. \end{align*}\)

Let \(y = 1/x^{3} + 3/x^{2} + 4/x + 5\) and find \(dy\).

Solution

Then \[dy = \left(-\dfrac{3}{x^{4}} - \frac{6}{x^{3}} - \frac{4}{x^{2}}\right) dx. \nonumber\]

Find \(dy\) where \[y = \left(\frac{1}{x^{2} + x} + 1\right)^{2}. \nonumber\]

Solution

This problem can be worked by means of a double substitution. Let \[u = x^{2} + x, \quad v = \frac{1}{u} + 1. \nonumber\]

Then \(y = v^{2}\).

We find \(dy\), \(dv\), and \(du\), \[\begin{align*} dy &= 2v \ dv, \\ dv &= -u^{-2} \ du, \\ du &= (2x + 1) \ dx. \end{align*}\]

Substituting, we get \(dy\) in terms of \(x\) and \(dx\), \[\begin{align*} dy &= 2v \left(-u^{-2} \ du\right) \\ &= -2vu^{-2} (2x + 1) dx \\ &= -2 \left(\frac{1}{u} + 1\right)u^{-2} (2x+1) dx \\ &= -2 \left(\frac{1}{x^{2} + x} + 1\right) \left(x^{2} + x\right)^{-2} (2x+1) \ dx \end{align*}\]

Assume that \(u\) and \(v\) depend on \(x\). Given \(y = (uv)^{-2}\), find \(dy/dx\) in terms of \(du/dx\) and \(dv/dx\).

Solution

Let \(s= uv\), whence \(y = s^{-2}\). We have \[\begin{align*} dy = -2s^{-3} \ ds, \\ ds &= u \ dv + v \ du. \end{align*}\]

Substituting \(dy = -2(uv)^{-3} (u \ dv + v \ du),\)

we get \[\frac{dy}{dx} = -2(uv)^{-3} \left(u \frac{dv}{dx} + v \frac{du}{dx}\right). \nonumber\]

The six rules for differentiation which we have proved in this section are so useful that they should be memorized. We list them all together.

| (1) | \(\dfrac{d (bx+c)}{dx} = b.\) | \(d(bx+c) = b \ dx.\) |

| (2) | \(\dfrac{d (u+v)}{dx} = \dfrac{du}{dx} + \dfrac{dv}{dx}.\) | \(d(u + v) = du + dv.\) |

| (3) | \(\dfrac{d(cu)}{dx} = c \dfrac{du}{dx}.\) | \(d(cu) = c \ du.\) |

| (4) | \(\dfrac{d (uv)}{dx} = u \dfrac{dv}{dx} + v \dfrac{du}{dx}.\) | \(d(uv) = u \ dv + v \ du.\) |

| (5) | \(\dfrac{d \left(u^{n}\right)}{dx} = nu^{n-1} \dfrac{du}{dx}.\) | \(d \left(u^{n}\right) = nu^{n-1} \ du\) (\(n\) is any integer). |

| (6) | \(\dfrac{u/v}{dx} = \dfrac{v \ du/dx - u \ dv/dx}{v^{2}}.\) | \(d(u/v) = \dfrac{v \ du - u \ dv}{v^{2}}.\) |

An easy way to remember the way the signs are in the Quotient Rule (Rule 6) is to put \(u = 1\) and use the Power Rule (Rule 5) with \(n = -1\), \[d(1/v) = d\left(v^{-1}\right) = -1 \cdot v^{-2} \ dv = \dfrac{-1 \ dv}{v^{2}}. \nonumber\]

Problems for Section 2.3

In Problems 1-42 below, find the derivative.

| 1. | \(f(x) = 3x^{2} + 5x - 4\) | 2. | \(s = \frac{1}{3}t^{3} + \frac{1}{2}t^{2} + t\) |

| 3. | \(y = (x+8)^{5}\) | 4. | \(z = 2(2 + 3x)^{4}\) |

| 5. | \(f(t) = (4-t)^{3}\) | 6. | \(g(x) = 3(2-5x)^{6}\) |

| 7. | \(y = \left(x^{2} + 5\right)^{3}\) | 8. | \(u = \left(6 + 2x^{2}\right)^{3}\) |

| 9. | \(u = \left(6 - 2x^{2}\right)^{3}\) | 10. | \(w = \left(1 + 4x^{3}\right)^{-2}\) |

| 11. | \(w = \left(1 - 4x^{3}\right)^{-2}\) | 12. | \(u = 1 + x^{-1} + x^{-2} + x^{-3}\) |

| 13. | \(f(x) = 5 (x + 1 - 1/x)\) | 14. | \(u = \left(x^{2} + 3x + 1\right)^{4}\) |

| 15. | \(v = 4 \left(2x^{2} - x + 3\right)^{-2}\) | 16. | \(y = -\left(2x + 3 + 4x^{-1}\right)^{-1}\) |

| 17. | \(y = \dfrac{1}{1 + 1/t}\) | 18. | \(y = \dfrac{1}{2x^{3} + 1}\) |

| 19. | \(s = \dfrac{-3}{4t^{2} - 2t + 1}\) | 20. | \(s = (2t+1)(3t-2)\) |

| 21. | \(h(x) = \frac{1}{2} \left(x^{2} + 1\right)(5 - 2x)\) | 22. | \(y = \left(2x^{3} + 4\right) \left(x^{2} - 3x + 1\right)\) |

| 23. | \(v = \left(3t^{2} + 1\right) (2t-4)^{3}\) | 24. | \(z = \left(-2x + 4 + 3x^{-1}\right) \left(x + 1 - 5x^{-1}\right)\) |

| 25. | \(y = \dfrac{x+1}{x-1}\) | 26. | \(w = \dfrac{2 - 3x}{1 + 2x}\) |

| 27. | \(y = \dfrac{x^{2} - 1}{x^{2} + 1}\) | 28. | \(u = \dfrac{x}{x^{2} + 1}\) |

| 29. | \(x = \dfrac{(s-1) (s-2)}{s-3}\) | 30. | \(y = \dfrac{t}{1 + 1/t}\) |

| 31. | \(y = \dfrac{2x^{-1} - x^{-2}}{3x^{-1} - 4x^{-2}}\) | 32. | \(y = 4x - 5\) |

| 33. | \(y = 6\) | 34. | \(y = 2x (3x - 1) (4 - 2x)\) |

| 35. | \(y = 3 \left(x^{2} + 1\right) \left(2x^{2} - 1\right) (2x + 3)\) | 36. | \(y = (4x + 3)^{-1} + (x-4)^{-2}\) |

| 37. | \(z = \dfrac{1}{(2x+1) (x-3)}\) | 38. | \(y = \left(x^{2} + 1\right)^{-1} (3x - 1)^{-2}\) |

| 39. | \(y = \left[(2x + 1)^{-1} + 3\right]^{-1}\) | 40. | \(s = \left[\left(t^{2} + 1\right) + t\right]^{-1}\) |

| 41. | \(y = (2x + 1)^{3} \left(x^{2} + 1\right)^{2}\) | 42. | \(y = \left(\dfrac{2}{x-1} - x^{-3}\right)^{4}\) |

In Problems 43-48, assume \(u\) and \(v\) depend on \(x\) and find \(dy/dx\) in terms of \(du/dx\) and \(dv/dx\).

| 43. | \(y = u-v\) | 44. | \(y = u^{2} v\) |

| 45. | \(y = 4u + v^{2}\) | 46. | \(y = 1/(u + v)\) |

| 47. | \(y = 1/uv\) | 48. | \(y = (u+v) (2u - v)\) |

| 49. | Find the line tangent to the curve \(y = 1 + x + x^{2} + x^{3}\) at the point \((1, 4)\). |

| 50. | Find the line tangent to the curve \(y = 9x^{-2}\) at the point \((3, 1)\). |

| \(\square\) 51. | Consider the parabola \(y = x^{2} + bx + c\). Find values of band \(c\) such that the line \(y = 2x\) is tangent to the parabola at the point \(x = 2, y = 4\). |

| \(\square\) 52. | Show that if \(u\), \(v\), and \(w\) are differentiable functions of \(x\) and \(y = uvw\), then \[\frac{dy}{dx} = uv \frac{dw}{dx} + uw \frac{dv}{dx} + vw \frac{du}{dx}. \nonumber\] |

| \(\square\) 53. | Use the principle of induction to show that if \(n\) is a positive integer, \(u_{1}, \ldots, u_{n}\) are differentiable functions of \(x\), and if \(y = u_{1} + \cdots + u_{n}\), then \[\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{du_{1}}{dx} + \cdots + \frac{du_{n}}{dx}. \nonumber\] |

| \(\square\) 54. | Use the principle of induction to prove that for every positive integer \(n\), \[1 + 2 + \cdots + n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2}. \nonumber\] |

| \(\square\) 55. | Every rational function can be written as a quotient of two polynomials, \(p(x)/q(x)\). Using this fact, show that the derivative of every rational function is a rational function. |