2.4: Inverse Functions

- Page ID

- 155803

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Two real functions \(f\) and \(g\) are called inverse functions if the two equations \[y = f(x), \quad x = g(y) \nonumber\]

have the same graphs in the \((x, y)\) plane. That is, a point \((x, y)\) is on the curve \(y = f(x)\) if, and only if, it is on the curve \(x = g(y)\). (In general, the graph of the equation \(x = g(y)\) is different from the graph of \(y = g(x)\), but is the same as the graph of \(y =f(x)\); see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).)

For example, the function \(y = x^{2}\), \(x \geq 0\) has the inverse function \(x = \sqrt{y}\); the function \(y = x^{3}\) has the inverse function \(x = \sqrt[3]{y}\).

If we think off as a black box operating on an input \(x\) to produce an output \(f(x)\), the inverse function \(g\) is a black box operating on the output \(f(x)\) to undo the

work of \(f\) and produce the original input \(x\) (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Many functions, such as \(y = x^{2}\), do not have inverse functions: In Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), we see that \(x\) is not a function of \(y\) because at \(y = 1\), \(x\) has the two values \(x = 1\) and \(x = -1\).

Often one can tell whether a function \(f\) has an inverse by looking at its graph. If there is a horizontal line \(y = c\) which cuts the graph at more than one point, the function \(f\) has no inverse. (See Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).) If no horizontal line cuts the graph at more than one point, then \(f\) has an inverse function \(g\). Using this rule, we can see in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) that the functions \(y = |x|\) and \(y = \sqrt{1 - x^{2}}\) do not have inverses.

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)shows some familiar functions which do have inverses. Note that in each case, \(\dfrac{dx}{dy} = \dfrac{1}{dy/dx}\).

| function \(y = f(x)\) | \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\) | inverse function \(x = g(y)\) | \(\dfrac{dx}{dy} = \dfrac{1}{dy/dx}\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\quad y = x+c\) | \(1\) | \(\quad x = y-c\) | \(1\) |

| \(\quad y = kx\) | \(k\) | \(\quad x = y/k\) | \(1/k\) |

| \(\quad y = x^{2}, \quad x \geq 0\) | \(2x\) | \(\quad x = \sqrt{y}\) | \(\dfrac{1}{2 \sqrt{y}} = \dfrac{1}{2x}\) |

| \(\quad y = x^{2}, \quad x \leq 0\) | \(2x\) | \(\quad x = -\sqrt{y}\) | \(-\dfrac{1}{2 \sqrt{y}} = \dfrac{1}{2x}\) |

| \(\quad y = 1/x\) | \(- \dfrac{1}{x^{2}}\) | \(\quad x = 1/y\) | \(-\dfrac{1}{y^{2}} = -x^{2}\) |

Suppose the \((x, y)\) plane is flipped over about the diagonal line \(y = x\). This will make the \(x\)- and \(y\)-axes change places, forming the \((y, x)\) plane. If \(f\) has an inverse function \(g\), the graph of the function \(y = f(x)\) will become the graph of the inverse function \(x = g(y)\) in the \((y, x)\) plane, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

The following rule shows that the derivatives of inverse functions are always reciprocals of each other.

Suppose \(f\) and \(g\) are inverse functions, so that the two equations \[y = f(x) \text{ and } x= g(y) \nonumber\]have the same graphs. If both derivatives \(f'(x)\) and \(g'(y)\) exist and are nonzero, then \[f'(x) = \frac{1}{g'(y)}. \nonumber\]

That is, \[\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{dx/dy}. \nonumber\]

Proof

Let \(\Delta x\) be a nonzero infinitesimal and let \(\Delta y\) be the corresponding change in \(y\). Then \(\Delta y\) is also infinitesimal because \(f'(x)\) exists and is nonzero because \(f(x)\) has an inverse function. By the rules for standard parts, \[\begin{align*} f'(x) \cdot g'(y) &= st \left(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\right) \cdot st \left(\frac{\Delta x}{\Delta y}\right) \\ &= st \left(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} \cdot \frac{\Delta x}{\Delta y}\right) = st(1) = 1. \end{align*}\]

Therefore, \[f'(x) = \frac{1}{g'(y)}. \nonumber\]

The formula \[\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{dx/dy}. \nonumber\]in the Inverse Function Rule is not as trivial as it looks. A more complete statement is \[\frac{dy}{dx} \text{ computed with } x \text{ the independent variable} = \frac{1}{dx/dy} \text{ computed with } y \text{ the independent variable.} \nonumber\]

Sometimes it is easier to compute \(dx/dy\) than \(dy/dx\), and in such cases the Inverse Function Rule is a useful method.

Find \(dy/dx\) where \(x = 1 + y^{-3}\).

Before solving the problem we note that \[y = \frac{1}{\sqrt[3]{x-1}, \nonumber\]

so \(x\) and \(y\) are inverse functions of each other. We want to find \[\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{d \left(1/\sqrt[3]{x-1}\right)}{dx} \nonumber\]

with \(x\) the independent variable. This looks hard, but it is easy to compute \[\frac{dx}{dy} = \frac{d \left(1 + y^{-3}\right)}{dy} \nonumber\]with \(y\) the independent variable.

Solution

\(\dfrac{dx}{dy} = -3y^{-4},\)

\(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = \dfrac{1}{-3y^{-4}} = \frac{1}{3} y^{4}.\)

We can write \(dy/dx\) in terms of \(x\) by substituting, \[\frac{dy}{dx} = -\frac{1}{3} (x-1)^{-4/3}. \nonumber\]

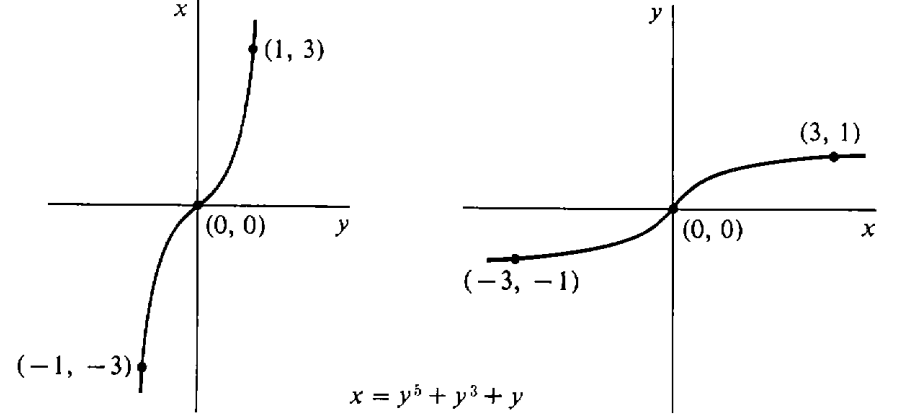

Find \(dy/dx\) where \(x = y^{5} + y^{3} + y\). Compute \(dy/dx\) at the point \((1, 3)\).

Solution

Although we cannot solve the equation explicitly for \(y\) as a function of \(x\), we can see from the graph in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) that there is an inverse function \(y = f(x)\).

By the Inverse Function Rule, \[\begin{align*} \frac{dx}{dy} &= 5y^{4} + 3y^{2} + 1, \\[4pt] \frac{dy}{dx} &= \frac{1}{5y^{4} + 3y^{2} + 1}. \end{align*}\]

This time we must leave the answer in terms of \(y\). At the point \((1, 3)\), we substitute \(3\) for \(y\) and get \(dy/dx = 1/9\).

For \(y \geq 0\), the function \(x = y^{n}\) has the inverse function \(y = x^{1/n}\). In the next theorem, we use the Inverse Function Rule to find a new derivative, that of \(y = x^{1/n}\).

If \(n\) is a positive integer and \(y = x^{1/n}\), then \[\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{n} x^{(1/n)-1}. \nonumber\]

Remember that \(y = x^{1/n}\) is defined for all \(x\) if \(n\) is odd and for \(x > 0\) if \(n\) is even. The derivative \(\dfrac{1}{n} x^{(1/n)-1}\) is defined for \(x \neq 0\) if \(n\) is odd and for \(x > 0\) if \(n\) is even.

If we are willing to assume that \(dy/dx\) exists, then we can quickly find \(dy/dx\) by the Inverse Function Rule. \[\begin{align*} x &= y^{n}, \\ \frac{dx}{dy} &= ny^{n-1}, \\ \frac{dy}{dx} &= \frac{1}{dx/dy} = \frac{1}{ny^{n-1}} = \frac{1}{n} y^{1-n} \\ &= \frac{1}{n} \left(x^{1/n}\right)^{1-n} = \frac{1}{n} x^{(1-n)/n} = \frac{1}{n} x^{(1/n)-1}. \end{align*}\]

Here is a longer but complete proof which shows that \(dy/dx\) exists and computes its value.

Proof

Let \(x \neq 0\) and let \(\Delta x\) be nonzero infinitesimal. We first show that \[\Delta y = (x + \Delta x)^{1/n} - x^{1/n} \nonumber\]is a nonzero infinitesimal. \(\Delta y \neq 0\) because \(x + \Delta x \neq x\). The standard part of \(\Delta y\) is \[\begin{align*} st (\Delta y) &= st \left( (x + \Delta x)^{1/n}\right) - st \left(x^{1/n}\right) \\ &= x^{1/n} - x^{1/n} = 0. \end{align*}\]Therefore \(\Delta y\) is nonzero infinitesimal.

Now \[\begin{align*} x &= y^{n}, \\[4pt] \frac{dx}{dy} &= ny^{n-1}, \\[4pt] \frac{\Delta x}{\Delta y} &\approx ny^{n-1}. \end{align*}\]

Therefore \[\begin{align*} \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} &\approx \frac{1}{ny^{n-1}} = \frac{1}{n} x^{(1/n) - 1}, \\[4pt] \frac{dy}{dx} &= \frac{1}{n} x^{(1/n) - 1}. \end{align*}\]

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) shows the graphs of \(y = x^{1/3}\) and \(y= x^{1/4}\). At \(x = 0\), the curves are vertical and have no slope.

Find the derivatives of \(y = x^{1/n}\) for \(n = 2, 3, 4\).

Solution

\[\begin{align*} \frac{d \left(x^{1/2}\right)}{dx} &= \frac{1}{2} x^{-1/2}, \quad x > 0, \\ \frac{d \left(x^{1/3}\right)}{dx} &= \frac{1}{3} x^{-2/3}, \quad x \neq 0, \\ \frac{d \left(x^{1/4}\right)}{dx} &= \frac{1}{4} x^{-3/4}, \quad x > 0. \end{align*}\]

Using Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\) we can show that the Power Rule holds when the exponent is any rational number.

Let \(y = x^{r}\) where \(r\) is a rational number. Then whenever \(x > 0\), \[\frac{dy}{dx} = rx^{r - 1}. \nonumber\]

Proof

Let \(r = m/n\) where \(m\) and \(n\) are integers, \(n > 0\). Let \[u = x^{1/n}, \quad y = u^{m}. \nonumber\]

Then \[\frac{du}{dx} = \frac{1}{n} x^{(1/n) - 1} \nonumber\]

and \[\begin{align*} \frac{dy}{dx} &= mu^{m-1} \frac{du}{dx} \\[4pt] &= m \left(x^{1/n}\right)^{m-1} \left(\frac{1}{n} x^{(1/n) - 1}\right) \\[4pt] &= \frac{m}{n} x^{(m/n) - 1} = rx^{r-1}. \end{align*}\]

Find \(dy/dx) where \[y = x^{-3/7}. \nonumber\]

Solution

\[\frac{dy}{dx} = -\frac{3}{7} x^{(-3/7) - 1} = -\frac{3}{7} x^{-10/7}. \nonumber\]

Find \(dy/dx) where \[y = \frac{1}{2 + x^{3/2}}. \nonumber\]

Solution

Let \[u = 2 + x^{3/2}, \quad y = u^{-1}. \nonumber\]

Then \[\begin{align*} \frac{du}{dx} &= \frac{3}{2} x^{1/2}, \\[4pt] \frac{dy}{dx} &= -u^{-2} \frac{du}{dx} \\[4pt] -u^{-2} \left(\frac{3}{2} x^{1/2}\right) = -\frac{3}{2} \frac{x^{1/2}}{\left(2 + x^{3/2}\right)^{2}}. \end{align*}\]

Problems for Section 2.4

In Problems 1-16, find \(dy/dx\).

| 1. | \(x= 3y^{3} + 2y\) | 2. | \(x = y^{2} + 1\) |

| 3. | \(x = 1 - 2y^{2}, \quad y > 0\) | 4. | \(x = 2y^{5} + y^{3} + 4\) |

| 5. | \(x = \left(y^{2} + 2\right)^{-1}, \quad y > 0\) | 6. | \(y = 1 + \sqrt{x}\) |

| 7. | \(y = x^{4/3}\) | 8. | \(y = \sqrt{2x}\) |

| 9. | \(y = \left(\sqrt{x} + 1\right) \left(\sqrt{x} - 1\right)\) | 10. | \(y = \left(2x^{1/3} + 1\right)^{3}\) |

| 11. | \(y = 1 + 2x^{1/3} + 4x^{2/3} + 6x\) | 12. | \(y = x^{-1/4} + 3x^{-3/4}\) |

| 13. | \(y = \left(x^{5/3} - x\right)^{-2}\) | 14. | \(x = y + 2 \sqrt{y}\) |

| 15. | \(x = 3y^{1/3} + 2y, \quad y > 0\) | 16. | \(x = 1/\left(1 + \sqrt{y}\right)\) |

In Problems 17-25, find the inverse function \(y\) and its derivative \(dy/dx\) as functions of \(x\).

| 17. | \(x = ky + c, \quad k \neq 0\) | 18. | \(x = y^{3} + 1\) |

| 19. | \(x = 2y^{2} + 1, \quad y \geq 0\) | 20. | \(x = 2y^{2} + 1, \quad y \leq 0\) |

| 21. | \(x = y^{4} - 3, \quad y \geq 0\) | 22. | \(x = y^{2} + 3y - 1, \quad y \geq -\frac{3}{2}\) |

| 23. | \(x = y^{4} + y^{2} + 1, \quad y \geq 0\) | 24. | \(x = 1/y^{2} + 1/y - 1, \quad y > 0\) |

| 25. | \(x = \sqrt{y} + 2y, \quad y > 0\) | ||

| \(\square\) 26. | Show that no second degree polynomial \(x = ay^{2} + by + c\) has an inverse function. | ||

| \(\square\) 27. | Show that \(x = ay^{2} + by + c, y \geq -b/2a\), has an inverse function. What does its graph look like? | ||

| \(\square\) 28. | Prove that a function \(y = f(x)\) has an inverse function if and only if whenever \(x_{1} \neq x_{2}\), \(f \left(x_{1}\right) \neq f \left(x_{2}\right)\). | ||