2.8: Quadratic Inequalities

- Page ID

- 193553

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Solve quadratic inequalities graphically

- Solve quadratic inequalities algebraically

We have learned how to solve linear inequalities and rational inequalities previously. Some of the techniques we used to solve them were the same and some were different. We will now learn to solve inequalities that have a quadratic expression. We will use some of the techniques from solving linear and rational inequalities as well as quadratic equations. We will solve quadratic inequalities two ways—both graphically and algebraically.

Solve Quadratic Inequalities Graphically

A quadratic equation is in standard form when written as \(ax^{2}+bx+c=0\). If we replace the equal sign with an inequality sign, we have a quadratic inequality in standard form.

The graph of a quadratic function \(f(x)=a x^{2}+b x+c=0\) is a parabola. When we ask when is \(a x^{2}+b x+c<0\), we are asking when is \(f(x)<0\). We want to know when the parabola is below the \(x\)-axis.

When we ask when is \(a x^{2}+b x+c>0\), we are asking when is \(f(x)>0\). We want to know when the parabola is above the \(y\)-axis.

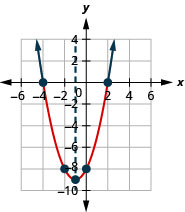

Solve \(x^{2}−6x+8<0\) graphically. Write the solution in interval notation.

Solution:

Step 1: Write the quadratic inequality in standard form.

The inequality is in standard form.

\(x^{2}-6 x+8<0\)

Step 2: Graph the function \(f(x)=a x^{2}+b x+c\) using properties or transformations.

We will graph using the properties so that we can practice everything we have learned.

\(f(x)=x^{2}-6 x+8\)

Look at \(a\) in the equation.

\(\color{red}{a=1, b=-6, c=8}\)

\(f(x)=x^{2}-6 x+8\)

Since \(a\) is positive, the parabola opens upward.

The parabola opens upward.

.png?revision=1)

\(f(x)=x^{2}-6 x+8\)

The axis of symmetry is the line \(x=-\frac{b}{2 a}\).

Axis of Symmetry

\(x=-\frac{b}{2 a}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}{x=-\frac{(-6)}{2 \cdot 1}} \\ {x=3}\end{array}\)

The axis of symmetry is the line \(x=3\).

The vertex is on the axis of symmetry. Substitute \(x=3\) into the function.

Vertex

\(\begin{array}{l}{f(x)=x^{2}-6 x+8} \\ {f(3)=(\color{red}{3}\color{black}{)}^{2}-6(\color{red}{3}\color{black}{)}+8} \\ {f(3)=-1}\end{array}\)

The vertex is \((3,-1)\).

We find \(f(0)\)

\(y\)-intercept

\(\begin{array}{l}{f(x)=x^{2}-6 x+8} \\ {f(0)=(\color{red}{0}\color{black}{)}^{2}-6(\color{red}{0}\color{black}{)}+8} \\ {f(0)=8}\end{array}\)

The \(y\)-intercept is \((0,8)\).

We use the axis of symmetry to find a point symmetric to the \(y\)-intercept. The \(y\)-intercept is \(3\) units left of the axis of symmetry, \(x=3\). A point \(3\) units to the right of the axis of symmetry has \(x=6\).

Point symmetric to \(y\)-intercept

The point is \((6,8)\).

We solve \(f(x)=0\).

\(x\)-intercepts

We can solve this quadratic equation by factoring.

\(\begin{aligned} f(x) &=x^{2}-6 x+8 \\ \color{red}{0} &\color{black}{=}x^{2}-6 x+8 \\ \color{red}{0} &\color{black}{=}(x-2)(x-4) \\ x &=2 \text { or } x=4 \end{aligned}\)

The \(x\)-intercepts are \((2,0)\) and \((4,0)\).

We graph the vertex, intercepts, and the point symmetric to the \(y\)-intercept. We connect these \(5\) points to sketch the parabola.

.png?revision=1)

Step 3: Determine the solution from the graph.

\(x^{2}-6 x+8<0\)

The inequality asks for the values of \(x\) which make the function less than \(0\). Which values of \(x\) make the parabola below the \(x\)-axis?

We do not include the values \(2\), \(4\) as the inequality is less than only.

The solution, in interval notation, is \((2,4)\) or in inequality notation \(2<x<4\)

For the rest of this section, we will keep our focus on inequalities and not review all of the information.

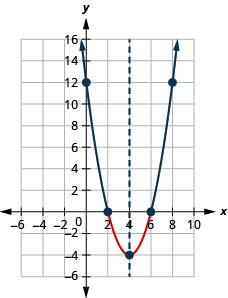

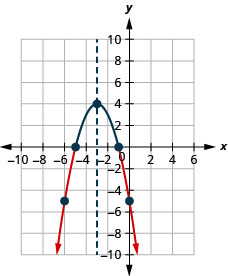

- Solve \(x^{2}+2x-8<0\) graphically

- Write the solution in interval notation

- Answer

-

Figure 2.8.4

b. \((-4,2)\)

- Solve \(x^{2}-8 x+12 \geq 0\) graphically

- Write the solution in interval notation

- Answer

-

Figure 2.8.5- \((-\infty, 2] \cup[6, \infty)\)

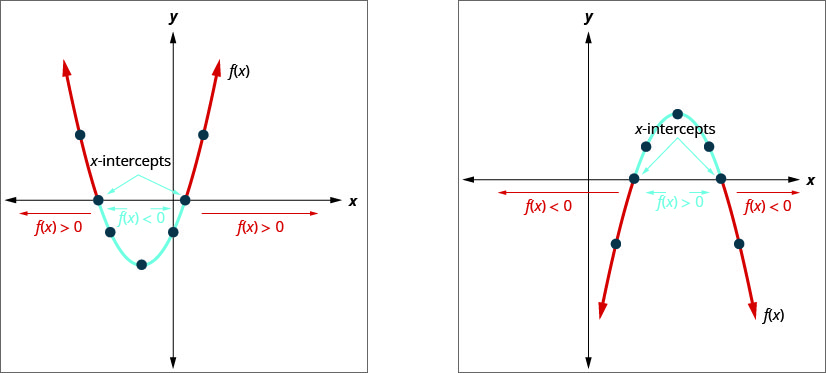

In the last example, the parabola opened upward and in the next example, it opens downward. In both cases, we are looking for the part of the parabola that is below the \(x\)-axis but note how the position of the parabola affects the solution.

Solve \(-x^{2}-8 x-12 \leq 0\) graphically. Write the solution in interval notation.

Solution:

| The quadratic inequality in standard form. | \(-x^{2}-8 x-12 \leq 0\) |

|

Graph the function \(f(x)=-x^{2}-8 x-12\) |

The parabola opens downward.

|

| Find the \(x\)-intercepts. Let \(f(x)=0\). | \(\begin{aligned} f(x) &=-x^{2}-8 x-12 \\ 0 &=-x^{2}-8 x-12 \end{aligned}\) |

| Factor: Use the Zero Product Property. | \(\begin{array}{l}{0=-1(x+6)(x+2)} \\ {x=-6 \quad x=-2}\end{array}\) |

| Graph the parabola. |

\(x\)-intercepts \((-6,0), (-2.0)\)

|

| Determine the solution from the graph. We include the \(x\)-intercepts as the inequality is "less than or equal to." | \((-\infty,-6] \cup[-2, \infty)\) |

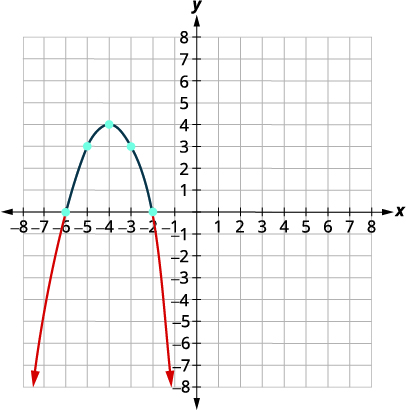

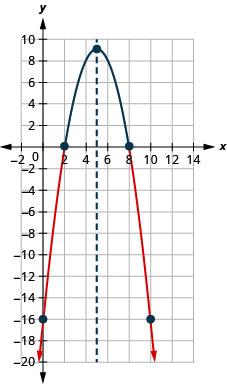

- Solve \(-x^{2}-6 x-5>0\) graphically

- Write the solution in interval notation

- Answer

-

Figure 2.8.8

- Solve \(−x^{2}+10x−16≤0\) graphically

- Write the solution in interval notation

- Answer

-

Figure 2.8.9- \((-\infty, 2] \cup[8, \infty)\)

Solve Quadratic Inequalities Algebraically

The algebraic method we will use is very similar to the method we used to solve rational inequalities. We will find the critical points for the inequality, which will be the solutions to the related quadratic equation. Remember a polynomial expression can change signs only where the expression is zero.

We will use the critical points to divide the number line into intervals and then determine whether the quadratic expression will be positive or negative in the interval. We then determine the solution for the inequality.

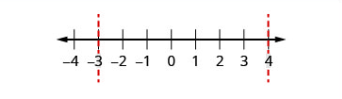

Solve \(x^{2}-x-12 \geq 0\) algebraically. Write the solution in interval notation.

Solution:

| Step 1: Write the quadratic inequality in standard form. | The inequality is in standard form. | \(x^{2}-x-12 \geq 0\) |

| Step 2: Determine the critical points--the solutions to the related quadratic equation. | Change the inequality sign to an equal sign and then solve the equation. | \(\begin{array}{c}{x^{2}-x-12=0} \\ {(x+3)(x-4)=0} \\ {x+3=0 \quad x-4=0} \\ {x=-3 \quad x=4}\end{array}\) |

| Step 3: Use the critical points to divide the number line into intervals. | Use \(-3\) and \(4\) to divide the number line into intervals. | .png?revision=1) |

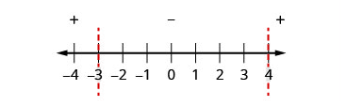

| Step 4: Above the number line show the sign of each quadratic expression using test points from each interval substituted from the original inequality. |

Test: \(x=-5\) \(x=0\) \(x=5\) |

\(\begin{array}{ccc}{x^{2}-x-12} & {x^{2}-x-12} & {x^{2}-x-12} \\ {(-5)^{2}-(-5)-12} & {0^{2}-0-12} & {5^{2}-5-12} \\ {18} & {-12} & {8}\end{array}\) .png?revision=1)

|

| Step 5: Determine the intervals where the inequality is correct. Write the solution in interval notation. |

\(x^{2}-x-12 \geq 0\) The inequality is positive in the first and last intervals and equals \(0\) at the points \(-4,3\). |

The solution, in interval notation, is \((-\infty,-3] \cup[4, \infty)\). |

Solve \(x^{2}+2x−8≥0\) algebraically. Write the solution in interval notation.

- Answer

-

Upon factoring the equation into \((x+4)(x-2)≥0\), we see the two critical points are \(-4\) and \(2\).

Using the critical points, we split the number line into intervals and check points in each interval.

The interval is positive in the first and last interval, therefore our solution is \((-\infty,-4] \cup[2, \infty)\)

Solve \(x^{2}−3x−10<0\) algebraically. Write the solution in interval notation.

- Answer

-

Upon factoring the equation into \((x-5)(x+2)≥0\), we see the two critical points are \(-2\) and \(5\).

Using the critical points, we split the number line into intervals and check points in each interval.

The interval is positive in the second interval, therefore our solution is \([-2,5]\)

Notice that the x-intercepts of the parabola are the same as the critical points of the parabola. When you know the x-intercepts and know if the parabola opens up or down, you can easily solve the quadratic inequality. The purple part of the graph is below the x-axis corresponding the x-values \(-2<x<5\).

As we have seen before, not every quadratic can be factored nicely into rational numbers or integers. Remember, we have other methods to solve quadratics.

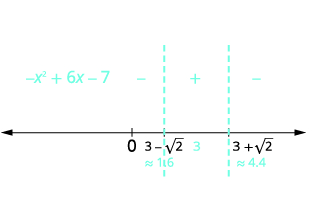

Solve \(-x^{2}+6x−7≥0\) algebraically. Write the solution in interval notation.

Solution:

| Write the quadratic inequality in standard form. | \(-x^{2}+6 x-7 \geq 0\) |

| Multiply both sides of the inequality by \(-1\). Remember to reverse the inequality sign. | \(x^{2}-6 x+7 \leq 0\) |

| Determine the critical points by solving the related quadratic equation. | \(x^{2}-6 x+7=0\) |

| Write the Quadratic Formula. | \(x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a}\) |

| Then substitute in the values of \(a, b, c\). | \(x=\frac{-(-6) \pm \sqrt{(-6)^{2}-4 \cdot 1 \cdot(7)}}{2 \cdot 1}\) |

| Simplify. | \(x=\frac{6 \pm \sqrt{8}}{2}\) |

| Simplify the radical. | \(x=\frac{6 \pm 2 \sqrt{2}}{2}\) |

| Remove the common factor, \(2\). | \(\begin{array}{l}{x=\frac{2(3 \pm \sqrt{2})}{2}} \\ {x=3 \pm \sqrt{2}} \\ {x=3+\sqrt{2}} \quad x=3-\sqrt{2} \\ {x \approx 1.6}\quad\quad\:\:\: x\approx 4.4\end{array}\) |

| Use the critical points to divide the number line into intervals. Test numbers from each interval in the original inequality. |  |

| Determine the intervals where the inequality is correct. Write the solution in interval notation. | \(-x^{2}+6 x-7 \geq 0\) in the middle interval \([3-\sqrt{2}, 3+\sqrt{2}]\) |

Solve \(−x^{2}+2x+1≥0\) algebraically. Write the solution in interval notation.

- Answer

-

First, multiply by \(-1\) to reverse the inequality \(x^{2}-2x-1 \le 0\). Noticing that the quadratic does not factor, we will use the quadratic formula to solve this inequality.

\(\begin{array}{l}{x=\frac{(-2 \pm \sqrt{8})}{2}} \\ {x=-\frac{(-2 \pm 2\sqrt{2})} {2}}\\ {x=-1+\sqrt{2}} \quad x=-1-\sqrt{2} \\ {x \approx 0.414}\quad\quad\:\:\: x\approx -2.414\end{array}\)\([-1-\sqrt{2},-1+\sqrt{2}]\)

Solve \(−x^{2}+8x−14<0\) algebraically. Write the solution in interval notation.

- Answer

-

First, multiply by \(-1\) to reverse the inequality to \(x^{2}-8x+14>0\) Noticing the quadratic does not factor. We will use the quadratic formula to solve for x and get the answers \((-\infty, 4-\sqrt{2}) \cup(4+\sqrt{2}, \infty)\)

The solutions of the quadratic inequalities in each of the previous examples were either an interval or the union of two intervals. This resulted from the fact that, in each case, we found two solutions to the corresponding quadratic equation \(ax^{2}+bx+c=0\). These two solutions then gave us either the two \(x\)-intercepts for the graph or the two critical points to divide the number line into intervals.

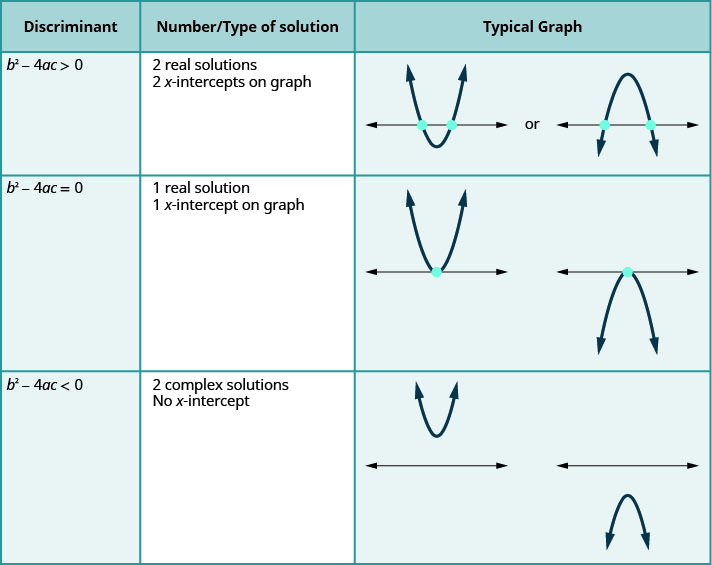

This correlates to our previous discussion of the number and type of solutions to a quadratic equation using the discriminant.

For a quadratic equation of the form \(ax^{2}+bc+c=0, a≠0\).

The last row of the table shows us when the parabolas never intersect the \(x\)-axis. Using the Quadratic Formula to solve the quadratic equation, the radicand is a negative number resulting in two complex solutions.

In the next example, solutions to the quadratic inequality will result from the solution of the quadratic equation being complex.

Solve, writing any solution in interval notation:

- \(x^{2}-3 x+4>0\)

- \(x^{2}-3 x+4 \leq 0\)

Solution:

a.

| Write the quadratic inequality in standard form. | \(-x^{2}-3 x+4>0\) |

| Determine the critical points by solving the related quadratic equation. | \(x^{2}-3 x+4=0\) |

| Write the Quadratic Formula. | \(x=\frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^{2}-4 a c}}{2 a}\) |

| Then substitute in the values of \(a, b, c\). | \(x=\frac{-(-3) \pm \sqrt{(-3)^{2}-4 \cdot 1 \cdot(4)}}{2 \cdot 1}\) |

| Simplify. | \(x=\frac{3 \pm \sqrt{-7}}{2}\) |

| Simplify the radicand. | \(x=\frac{3 \pm \sqrt{7 i}}{2}\) |

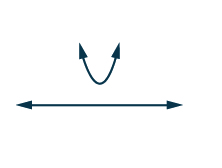

| The complex solutions tell us the parabola does not intercept the \(x\)-axis. Also, the parabola opens upward. This tells us that the parabola is completely above the \(x\)-axis. |

Complex solutions

|

We are to find the solution to \(x^{2}−3x+4>0\). Since for all values of \(x\) the graph is above the \(x\)-axis, all values of \(x\) make the inequality true. In interval notation we write \((−∞,∞)\).

b. Write the quadratic inequality in standard form.

\(x^{2}-3 x+4 \leq 0\)

Determine the critical points by solving the related quadratic equation.

\(x^{2}-3 x+4=0\)

Since the corresponding quadratic equation is the same as in part (a), the parabola will be the same. The parabola opens upward and is completely above the \(x\)-axis—no part of it is below the \(x\)-axis.

We are to find the solution to \(x^{2}−3x+4≤0\). Since for all values of \(x\) the graph is never below the \(x\)-axis, no values of \(x\) make the inequality true. There is no solution to the inequality.

Solve and write any solution in interval notation:

- \(-x^{2}+2 x-4 \leq 0\)

- \(-x^{2}+2 x-4 \geq 0\)

- Answer

-

- \((-\infty, \infty)\)

- no solution

Key Concepts

- Solve a Quadratic Inequality Graphically

- Write the quadratic inequality in standard form.

- Graph the function \(f(x)=ax^{2}+bx+c\) using properties or transformations.

- Determine the solution from the graph.

- How to Solve a Quadratic Inequality Algebraically

- Write the quadratic inequality in standard form.

- Determine the critical points -- the solutions to the related quadratic equation.

- Use the critical points to divide the number line into intervals.

- Above the number line show the sign of each quadratic expression using test points from each interval substituted into the original inequality.

- Determine the intervals where the inequality is correct. Write the solution in interval notation.