2.10: Variation

- Page ID

- 193554

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

In this section, you will:- Solve direct variation problems.

- Solve inverse variation problems.

- Solve problems involving joint variation.

Perhaps you have noticed that filling up your vehicle with fuel is very expensive. A used-car company has just offered its best candidate, Nicole, a sales position. The position offers 16% commission on her sales. Her earnings depend on the amount of her sales. For instance, if she sells a vehicle for $4,600, she will earn $736. She wants to evaluate the offer, but she is not sure how. In this section, we will examine relationships, such as the one between earnings, sales, and the commission rate.

Solving Direct Variation Problems

In the example above, Nicole’s earnings can be calculated by multiplying her sales by her commission rate. The formula \(t=0.16s\) tells us that her total, \(t\), are the product of \(0.16\), her commission, and the sale price of the vehicle. If we create a table, we observe that as the sales price increases, the earnings increase as well, which should be intuitive. See Table 2.10.1.

| \(s\), sales price | \(t=0.16s\) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| $9,200 | \(t=0.16(9,200)=1,472\) | A sale of a \($9,200\)vehicle results in \($1472\) earnings. |

| $4,600 | \(t=0.16(4,600)=736\) | A sale of a \($4,600\) vehicle results in \($736\) earnings. |

| $18,400 | \(t=0.16(18,400)=2,944\) | A sale of a \($18,400\) vehicle results in \($2944\) earnings. |

Table 2.10.1

Notice that earnings are a multiple of sales. As sales increase, earnings increase in a predictable way. Double the sales of the vehicle from $4,600 to $9,200, and we double the earnings from \($736\) to \($1,472.\) As the input increases, the output increases as a multiple of the input. A relationship in which one quantity is a constant multiplied by another quantity is called direct variation. Each variable in this type of relationship varies directly with the other.

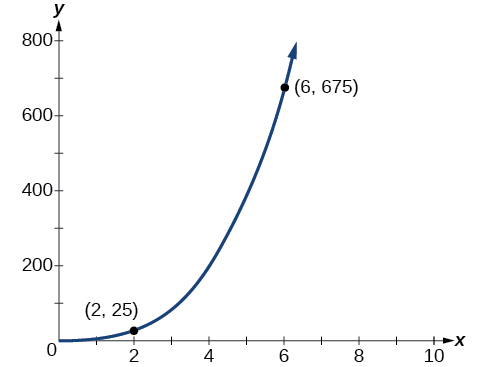

Figure 2.10.1 represents the data for Nicole’s potential earnings. We say that earnings vary directly with the sales price of the car. The formula \(y=kx^n\) is used for direct variation. The value \(k\) is a nonzero constant greater than zero and is called the constant of variation. In this case, \(k=0.16\) and \(n=1\). We saw functions like this one when we discussed power functions.

A General Note: DIRECT VARIATION

If \(x\) and \(y\) are related by an equation of the form

\(y=kx^n\)

then we say that the relationship is direct variation and \(y\) varies directly with, or is proportional to, the \(n\)th power of \(x\). In direct variation relationships, there is a nonzero constant ratio \(k=\dfrac{y}{x^n}\), where \(k\) is called the constant of variation, which defines the relationship between the variables.

The quantity \(y\) varies directly with the cube of \(x\). If \(y=25\) when \(x=2\), find \(y\) when \(x\) is \(6\).

Solution

The general formula for direct variation with a cube is \(y=kx^3\). The constant can be found by dividing \(y\) by the cube of \(x\).

\(k=\dfrac{y}{x^3}\)

\(=\dfrac{25}{2^3}\)

\(=\dfrac{25}{8}\)

Now use the constant to write an equation that represents this relationship.

\(y=\dfrac{25}{8}x^3\)

Substitute \(x=6\) and solve for \(y\).

\(y=\dfrac{25}{8}{(6)}^3\)

\(=675\)

Analysis

The graph of this equation is a simple cubic, as shown in Figure 2.10.2.

Q&A

Do the graphs of all direct variation equations look like the one above?

No. Direct variation equations are power functions—they may be linear, quadratic, cubic, quartic, radical, etc. But all of the graphs pass through \((0,0)\).

The quantity \(y\) varies directly with the square of \(x\). If \(y=24\) when \(x=3\), find \(y\) when \(x\) is 4.

- Answer

-

The general formula for direct variation with a cube is \(y=kx^2\). The constant can be found by dividing \(y\) by the square of \(x\).

\(k=\dfrac{y}{x^2}\)

\(=\dfrac{24}{3^2}\)

\(=\dfrac{24}{9}\)

\(=\dfrac{8}{3}\)

Now use the constant to write an equation that represents this relationship.

\(y=\dfrac{8}{3}x^2\)

Substitute \(x=4\) and solve for \(y\).

\(y=\dfrac{8}{3}{(4)}^2\)

\(\frac{128}{3}\)

Analysis

The graph of this equation is a simple quadratic, as shown in Figure 2.10.2.

Figure 2.10.2

Figure 2.10.2

Solving Inverse Variation Problems

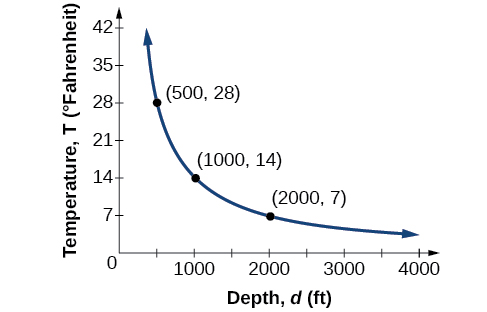

Water temperature in an ocean varies inversely to the water’s depth. The formula \(T=\frac{14,000}{d}\) gives us the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit at a depth in feet below Earth’s surface. Consider the Atlantic Ocean, which covers \(22%\) of Earth’s surface. At a certain location, at the depth of \(500\) feet, the temperature may be \(28°\)F.

If we create Table 2.10.2, we observe that, as the depth increases, the water temperature decreases.

| \(d\), depth | \(T=\frac{14,000}{d}\) | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(500\) ft | \(\frac{14,000}{500}=28\) | At a depth of \(500\) ft, the water temperature is \(28°\) F. | |

| \(1000\) ft | \(\frac{14,000}{1000}=14\) | At a depth of \(1,000\) ft, the water temperature is \(14°\) F. | |

| \(2000\) ft | \(\frac{14,000}{2000}=7\) | At a depth of \(2,000\) ft, the water temperature is \(7°\) F. |

Table 2.10.2

We notice in the relationship between these variables that, as one quantity increases, the other decreases. The two quantities are said to be inversely proportional and each term varies inversely with the other. Inversely proportional relationships are also called inverse variations.

For our example, Figure 2.10.3 depicts the inverse variation. We say the water temperature varies inversely with the depth of the water because, as the depth increases, the temperature decreases. The formula \(y=\frac{k}{x}\) for inverse variation in this case uses \(k=14,000\).

A General Note: INVERSE VARIATION

If \(x\) and \(y\) are related by an equation of the form

\(y=\frac{k}{x^n}\)

where \(k\) is a nonzero constant, then we say that \(y\) varies inversely with the \(n\)th power of \(x\). In inversely proportional relationships, or inverse variations, there is a constant multiple \(k=x^ny\).

Example : Writing a Formula for an Inverse Relationship

A tourist plans to drive 100 miles. Find a formula for the time the trip will take as a function of the speed the tourist drives.

Solution

Recall that multiplying speed by time gives distance. If we let \(t\) represent the drive time in hours, and \(v\) represent the velocity (speed or rate) at which the tourist drives, then \(vt=\)distance. Because the distance is fixed at 100 miles, \(vt=100\) so \(t=\frac{100}{v}\). Because time is a function of velocity, we can write \(t(v)\).

\(t(v)=\frac{100}{v}\)

\(=100v^{−1}\)

We can see that the constant of variation is \(100\) and, although we can write the relationship using the negative exponent, it is more common to see it written as a fraction. We say that time varies inversely with velocity.

Example : Solving an Inverse Variation Problem

A quantity \(y\) varies inversely with the cube of \(x\). If \(y=25\) when \(x=2\), find \(y\) when \(x\) is \(6\).

Solution

The general formula for inverse variation with a cube is \(y=\frac{k}{x^3}\). The constant can be found by multiplying \(y\) by the cube of \(x\).

\(k=x^3y\)

\(=2^3⋅25\)

\(=200\)

Now we use the constant to write an equation that represents this relationship.

\(y=\dfrac{k}{x^3}\), \( k=200\)

\(y=\dfrac{200}{x^3}\)

Substitute \(x=6\) and solve for \(y\).

\(y=\dfrac{200}{6^3}\)

\(=\dfrac{25}{27}\)

Analysis

The graph of this equation is a rational function, as shown in Figure 2.10.4.

A quantity \(y\) varies inversely with the square of \(x\). If \(y=8\) when \(x=3\), find \(y\) when \(x\) is \(4\).

- Answer

-

The general formula for inverse variation with a square is \(y=\frac{k}{x^2}\). The constant can be found by multiplying \(y\) by the square of \(x\).

\(k=x^2y\)

\(=3^2⋅8\)

\(=72\)

Now we use the constant to write an equation that represents this relationship.

\(y=\dfrac{k}{x^2}\), \( k=72\)

\(y=\dfrac{72}{x^2}\)

Substitute \(x=4\) and solve for \(y\).

\(y=\dfrac{72}{4^2}\)

\(=\dfrac{9}{8}\)

Analysis

The graph of this equation is a rational function, as shown in Figure 2.10.4.

Figure 2.10.4

Figure 2.10.4

Solving Problems Involving Joint Variation

Many situations are more complicated than a basic direct variation or inverse variation model. One variable often depends on multiple other variables. When a variable is dependent on the product or quotient of two or more variables, this is called joint variation. For example, the cost of busing students for each school trip varies with the number of students attending and the distance from the school. The variable \(c\),cost, varies jointly with the number of students, \(n\),and the distance, \(d\).

A General Note: JOINT VARIATION

Joint variation occurs when a variable varies directly or inversely with multiple variables.

For instance, if \(x\) varies directly with both \(y\) and \(z\), we have \(x=kyz\). If \(x\) varies directly with \(y\) and inversely with \(z\),we have \(x=\frac{ky}{z}\). Notice that we only use one constant in a joint variation equation.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Solving an Inverse Variation Problem

A quantity \(x\) varies directly with the square of \(y\) and inversely with the cube root of \(z\). If \(x=6\) when \(y=2\) and \(z=8\), find \(x\) when \(y=1\) and \(z=27\).

Solution

Begin by writing an equation to show the relationship between the variables.

\(x=\dfrac{ky^2}{\sqrt[3]{z}}\)

Substitute \(x=6\), \(y=2\), and \(z=8\) to find the value of the constant \(k\).

\(6=\dfrac{k2^2}{\sqrt[3]{8}}\)

\(6=\dfrac{4k}{2}\)

\(3=k\)

Now we can substitute the value of the constant into the equation for the relationship.

\(x=\dfrac{3y^2}{\sqrt[3]{z}}\)

To find \(x\) when \(y=1\) and \(z=27\), we will substitute values for \(y\) and \(z\) into our equation.

\(x=\dfrac{3{(1)}^2}{\sqrt[3]{27}}\)

\(=1\)

A quantity \(x\) varies directly with the square of \(y\) and inversely with \(z\). If \(x=40\) when \(y=4\) and \(z=2\), find \(x\) when \(y=10\) and \(z=25\).

- Answer

-

Begin by writing an equation to show the relationship between the variables.

\(x=\dfrac{ky^2}{z}\)

Substitute \(x=40\), \(y=4\), and \(z=2\) to find the value of the constant \(k\).

\(40=\dfrac{k4^2}{2}\)

\(40=\frac{16k}{2}\)

\(40=8k\)

\(5=k\)

Now we can substitute the value of the into the equation for the relationship.

\(x=\dfrac{5y^2}{z}\)

To find \(x\) when \(y=10\) and \(z=25\), we will substitute values for \(y\) and \(z\) into our equation.

\(x=\dfrac{5{(10)}^2}25\)

\(=20\)

Key Concepts

- A relationship where one quantity is a constant multiplied by another quantity is called direct variation.

- Two variables that are directly proportional to one another will have a constant ratio.

- A relationship where one quantity is a constant divided by another quantity is called inverse variation.

- Two variables that are inversely proportional to one another will have a constant multiple.

- In many problems, a variable varies directly or inversely with multiple variables. We call this type of relationship joint variation.