4.5: Logarithmic Functions

- Page ID

- 193560

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Convert from logarithmic to exponential form.

- Convert from exponential to logarithmic form.

- Evaluate logarithms.

- Use common logarithms.

- Use natural logarithms.

In 2010, a major earthquake struck Haiti, destroying or damaging over 285,000 homes. One year later, another, stronger earthquake devastated Honshu, Japan, destroying or damaging over 332,000 buildings, like those shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Even though both caused substantial damage, the earthquake in 2011 was 100 times stronger than the earthquake in Haiti. How do we know? The magnitudes of earthquakes are measured on a scale known as the Richter Scale. The Haitian earthquake registered a 7.0 on the Richter Scale whereas the Japanese earthquake registered a 9.0.

The Richter Scale is a base-ten logarithmic scale. In other words, an earthquake of magnitude \(8\) is not twice as great as an earthquake of magnitude \(4\). It is

\[10^{8−4}=10^4=10,000 \nonumber\]

times as great! In this lesson, we will investigate the nature of the Richter Scale and the base-ten function upon which it depends.

Converting from Logarithmic to Exponential Form

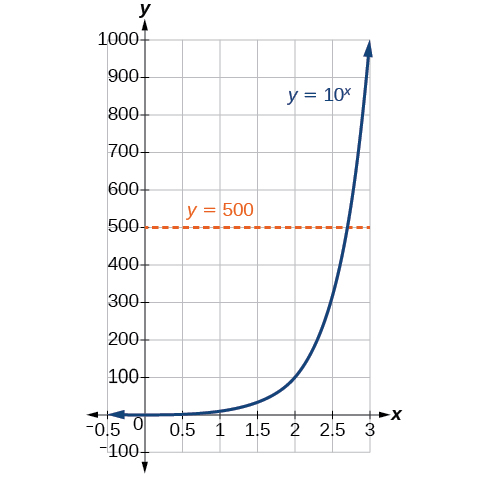

In order to analyze the magnitude of earthquakes or compare the magnitudes of two different earthquakes, we need to be able to convert between logarithmic and exponential form. For example, suppose the amount of energy released from one earthquake were 500 times greater than the amount of energy released from another. We want to calculate the difference in magnitude. The equation that represents this problem is \(10^x=500\), where \(x\) represents the difference in magnitudes on the Richter Scale. How would we solve for \(x\)?

We have not yet learned a method for solving exponential equations. None of the algebraic tools discussed so far is sufficient to solve \(10^x=500\). We know that \({10}^2=100\) and \({10}^3=1000\), so it is clear that \(x\) must be some value between 2 and 3, since \(y={10}^x\) is increasing. We can examine a graph, as in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), to better estimate the solution.

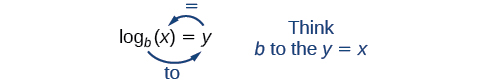

Estimating from a graph, however, is imprecise. To find an algebraic solution, we must introduce a new function. Observe that the graph in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) passes the horizontal line test. The exponential function \(y=b^x\) is one-to-one, so its inverse, \(x=b^y\) is also a function. As is the case with all inverse functions, we simply interchange \(x\) and \(y\) and solve for \(y\) to find the inverse function. To represent \(y\) as a function of \(x\), we use a logarithmic function of the form \(y={\log}_b(x)\). The base \(b\) logarithm of a number is the exponent by which we must raise \(b\) to get that number.

We read a logarithmic expression as, “The logarithm with base \(b\) of \(x\) is equal to \(y\),” or, simplified, “log base \(b\) of \(x\) is \(y\).” We can also say, “\(b\) raised to the power of \(y\) is \(x\),” because logs are exponents. For example, the base \(2\) logarithm of \(32\) is \(5\), because \(5\) is the exponent we must apply to \(2\) to get \(32\). Since \(2^5=32\), we can write \({\log}_232=5\). We read this as “log base \(2\) of \(32\) is \(5\).”

We can express the relationship between logarithmic form and its corresponding exponential form as follows:

\[\begin{align} \log_b(x)=y\Leftrightarrow b^y=x, b> 0, b\neq 1 \end{align}\]

Note that the base \(b\) is always positive.

Because logarithm is a function, it is most correctly written as \(\log_b(x)\), using parentheses to denote function evaluation, just as we would with \(f(x)\). However, when the input is a single variable or number, it is common to see the parentheses dropped and the expression written without parentheses, as \(\log_bx\). Note that many calculators require parentheses around the \(x\).

Write the following logarithmic equations in exponential form.

- \({\log}_6(\sqrt{6})=\dfrac{1}{2}\)

- \({\log}_3(9)=2\)

Solution

First, identify the values of \(b\), \(y\),and \(x\). Then, write the equation in the form \(b^y=x\).

- \({\log}_6(\sqrt{6})=\dfrac{1}{2}\)

Here, \(b=6\), \(y=\dfrac{1}{2}\),and \(x=\sqrt{6}\). Therefore, the equation \({\log}_6(\sqrt{6})=\dfrac{1}{2}\) is equivalent to

\(6^{\tfrac{1}{2}}=\sqrt{6}\)

- \({\log}_3(9)=2\)

Here, \(b=3\), \(y=2\),and \(x=9\). Therefore, the equation \({\log}_3(9)=2\) is equivalent to

\(3^2=9\)

Write the following logarithmic equations in exponential form.

- \({\log}_{10}(1,000,000)=6\)

- \({\log}_5(25)=2\)

- Answer a

-

Here, \(b=10\), \(y=6\),and \(x=1,000,000\). Therefore, the equation \({\log}_{10}{1000000}=6\) is equivalent to

\(10^{6}=1,000,000\)

- Answer b

-

\({\log}_5(25)=2\) is equivalent to \(5^2=25\)

Converting from Exponential to Logarithmic Form

To convert from exponents to logarithms, we follow the same steps in reverse. We identify the base \(b\),exponent \(x\),and output \(y\). Then we write \(x={\log}_b(y)\).

Write the following exponential equations in logarithmic form.

- \(2^3=8\)

- \(5^2=25\)

- \({10}^{−4}=\dfrac{1}{10,000}\)

Solution

First, identify the values of \(b\), \(y\),and \(x\). Then, write the equation in the form \(x={\log}_b(y)\).

- \(2^3=8\)

Here, \(b=2\), \(x=3\),and \(y=8\). Therefore, the equation \(2^3=8\) is equivalent to \({\log}_2(8)=3\).

- \(5^2=25\)

Here, \(b=5\), \(x=2\),and \(y=25\). Therefore, the equation \(5^2=25\) is equivalent to \({\log}_5(25)=2\).

- \({10}^{−4}=\dfrac{1}{10,000}\)

Here, \(b=10\), \(x=−4\),and \(y=\dfrac{1}{10,000}\). Therefore, the equation \({10}^{−4}=\dfrac{1}{10,000}\) is equivalent to \({\log}_{10} \left (\dfrac{1}{10,000} \right )=−4\).

Write the following exponential equations in logarithmic form.

- \(3^2=9\)

- \(5^3=125\)

- \(2^{−1}=\dfrac{1}{2}\)

- Answer a

-

\(3^2=9\) is equivalent to \({\log}_3(9)=2\)

- Answer b

-

\(5^3=125\) is equivalent to \({\log}_5(125)=3\)

- Answer c

-

\(2^{−1}=\dfrac{1}{2}\) is equivalent to \({\log}_2 \left (\dfrac{1}{2} \right )=−1\)

Evaluating Logarithms

Knowing the squares, cubes, and roots of numbers allows us to evaluate many logarithms mentally. For example, consider \({\log}_28\). We ask, “To what exponent must \(2\) be raised in order to get 8?” Because we already know \(2^3=8\), it follows that \({\log}_28=3\).

Now consider solving \({\log}_749\) and \({\log}_327\) mentally.

- We ask, “To what exponent must \(7\) be raised in order to get \(49\)?” We know \(7^2=49\). Therefore, \({\log}_749=2\)

- We ask, “To what exponent must \(3\) be raised in order to get \(27\)?” We know \(3^3=27\). Therefore, \(\log_{3}27=3\)

Even some seemingly more complicated logarithms can be evaluated without a calculator. For example, let’s evaluate \(\log_{\ce{2/3}} \frac{4}{9}\) mentally.

- We ask, “To what exponent must \(\ce{2/3}\) be raised in order to get \(\ce{4/9}\)? ” We know \(2^2=4\) and \(3^2=9\), so \[{\left(\dfrac{2}{3} \right )}^2=\dfrac{4}{9}. \nonumber\] Therefore, \[{\log}_{\ce{2/3}} \left (\dfrac{4}{9} \right )=2. \nonumber\]

Solve \(y={\log}_4(64)\) without using a calculator.

Solution

First we rewrite the logarithm in exponential form: \(4^y=64\). Next, we ask, “To what exponent must \(4\) be raised in order to get \(64\)?”

We know

\(4^3=64\)

Therefore,

\({\log}_4(64)=3\)

Solve \(y={\log}_{121}(11)\) without using a calculator.

- Answer

-

\({\log}_{121}(11)=\dfrac{1}{2}\) (recalling that \(\sqrt{121}={(121)}^{\tfrac{1}{2}}=11)\)

Evaluate \(y={\log}_3 \left (\dfrac{1}{27} \right )\) without using a calculator.

Solution

First we rewrite the logarithm in exponential form: \(3^y=\dfrac{1}{27}\). Next, we ask, “To what exponent must \(3\) be raised in order to get \(\dfrac{1}{27}\)?”

We know \(3^3=27\),but what must we do to get the reciprocal, \(\dfrac{1}{27}\)? Recall from working with exponents that \(b^{−a}=\dfrac{1}{b^a}\). We use this information to write

\[\begin{align*} 3^{-3}&= \dfrac{1}{3^3}\\ &= \dfrac{1}{27} \end{align*}\]

Therefore, \({\log}_3 \left (\dfrac{1}{27} \right )=−3\).

Evaluate \(y={\log}_2 \left (\dfrac{1}{32} \right )\) without using a calculator.

- Answer

-

\({\log}_2 \left (\dfrac{1}{32} \right )=−5\)

Using Common Logarithms

Sometimes we may see a logarithm written without a base. In this case, we assume that the base is \(10\). In other words, the expression \(\log(x)\) means \({\log}_{10}(x)\). We call a base \(10\) logarithm a common logarithm. Common logarithms are used to measure the Richter Scale mentioned at the beginning of the section. Scales for measuring the brightness of stars and the pH of acids and bases also use common logarithms.

A common logarithm is a logarithm with base \(10\). We write \({\log}_{10}(x)\) simply as \(\log(x)\). The common logarithm of a positive number \(x\) satisfies the following definition.

For \(x>0\),

\[\begin{align} y={\log}(x)\text{ is equivalent to } {10}^y=x \end{align}\]

We read \(\log(x)\) as, “the logarithm with base \(10\) of \(x\) ” or “log base \(10\) of \(x\).”

The logarithm \(y\) is the exponent to which \(10\) must be raised to get \(x\).

Evaluate \(y=\log(1000)\) without using a calculator.

Solution

First we rewrite the logarithm in exponential form: \({10}^y=1000\). Next, we ask, “To what exponent must \(10\) be raised in order to get \(1000\)?” We know

\({10}^3=1000\)

Therefore, \(\log(1000)=3\).

The amount of energy released from one earthquake was \(500\) times greater than the amount of energy released from another. The equation \({10}^x=500\) represents this situation, where \(x\) is the difference in magnitudes on the Richter Scale. To the nearest thousandth, what was the difference in magnitudes?

Solution

We begin by rewriting the exponential equation in logarithmic form.

\({10}^x=500\)

\(\log(500)=x\) Use the definition of the common log.

Next we evaluate the logarithm using a calculator:

- To the nearest thousandth, \(\log(500)≈2.699\).

The difference in magnitudes was about \(2.699\).

The amount of energy released from one earthquake was \(8,500\) times greater than the amount of energy released from another. The equation \({10}^x=8500\) represents this situation, where \(x\) is the difference in magnitudes on the Richter Scale. To the nearest thousandth, what was the difference in magnitudes?

- Answer

-

We begin by rewriting the exponential equation in logarithmic form.

\({10}^x=8500\)

\(\log(8500)=x\) Use the definition of the common log.

Next, we evaluate the logarithm using a calculator:

The difference in magnitudes was about \(3.929\).

Using Natural Logarithms

The most frequently used base for logarithms is \(e\). Base \(e\) logarithms are important in calculus and some scientific applications; they are called natural logarithms. The base \(e\) logarithm, \({\log}_e(x)\), has its own notation,\(\ln(x)\). Most values of \(\ln(x)\) can be found only using a calculator. The major exception is that, because the logarithm of \(1\) is always \(0\) in any base, \(\ln1=0\). For other natural logarithms, we can use the \(\ln\) key that can be found on most scientific calculators. We can also find the natural logarithm of any power of \(e\) using the inverse property of logarithms.

A natural logarithm is a logarithm with base \(e\). We write \({\log}_e(x)\) simply as \(\ln(x)\). The natural logarithm of a positive number \(x\) satisfies the following definition.

For \(x>0\),

\(y=\ln(x)\) is equivalent to \(e^y=x\)

We read \(\ln(x)\) as, “the logarithm with base \(e\) of \(x\)” or “the natural logarithm of \(x\).”

The logarithm \(y\) is the exponent to which \(e\) must be raised to get \(x\).

Since the functions \(y=e^x\) and \(y=\ln(x)\) are inverse functions, \(\ln(e^x)=x\) for all \(x\) and \(e^{\ln (x)}=x\) for \(x>0\).

Evaluate \(y=\ln(500)\) to four decimal places using a calculator.

Solution

Rounding to four decimal places, \(\ln(500)≈6.2146\)

Key Concepts

| Definition of the logarithmic function | For \(x>0\), \(b>0\), \(b≠1\), \(y={\log}_b(x)\) if and only if \(b^y=x\). |

| Definition of the common logarithm | For \(x>0\), \(y=\log(x)\) if and only if \({10}^y=x\). |

| Definition of the natural logarithm | For \(x>0\), \(y=\ln(x)\) if and only if \(e^y=x\). |

- The inverse of an exponential function is a logarithmic function, and the inverse of a logarithmic function is an exponential function.

- Logarithmic equations can be written in an equivalent exponential form, using the definition of a logarithm.

- Exponential equations can be written in their equivalent logarithmic form using the definition of a logarithm.

- Logarithmic functions with base \(b\) can be evaluated mentally using previous knowledge of powers of \(b\).

- Common logarithms can be evaluated mentally using previous knowledge of powers of \(10\).

- When common logarithms cannot be evaluated mentally, a calculator can be used.

- Real-world exponential problems with base \(10\) can be rewritten as a common logarithm and then evaluated using a calculator.

- Natural logarithms can be evaluated using a calculator.