5.06: Extrapolation is a Bad Idea

- Page ID

- 126412

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Lesson 1: Extrapolation is a Bad Idea

Learning Objectives

After successful completion of this lesson, you should be able to:

1) enumerate why using extrapolation can be a bad idea.

2) show through an example why extrapolation can be a bad idea.

Description

This conversation illustrates the pitfall of using extrapolation.

(Due to certain reasons, this student wishes to remain anonymous.)

This takes place in Summer Session B – July 2001

Student: “Hey, Dr. Kaw! Look at this cool new cell phone I just got!”

Kaw: “That’s nice. It better not ring in my class or it’s mine.”

Student: “What would you think about getting stock in this company?”

Kaw: “What company is that?”

Student: “WorldCom! They’re the world’s leading global data and internet company.”

Kaw: “So?”

Student: “They’ve just closed the deal today to merge with Intermedia Communications, based right here in Tampa!”

Kaw: “Yeah, and …?”

Student: “The stock’s booming! It’s at $14.11 per share and promised to go only one way—up! We’ll be millionaires if we invest now!”

Kaw: “You might not want to assume their stock will keep rising … besides, I’m skeptical of their success. I don’t want you putting yourself in financial ‘jeopardy!’ over some silly extrapolation. Take a look at these NASDAQ composite numbers (Table \(\PageIndex{1.1}\)).”

Student: “That’s only up to two years ago …”

Kaw: “That’s right. Looking at this data, don’t you think you should’ve invested back then?”

Student: “Well, didn’t the composite drop after that?”

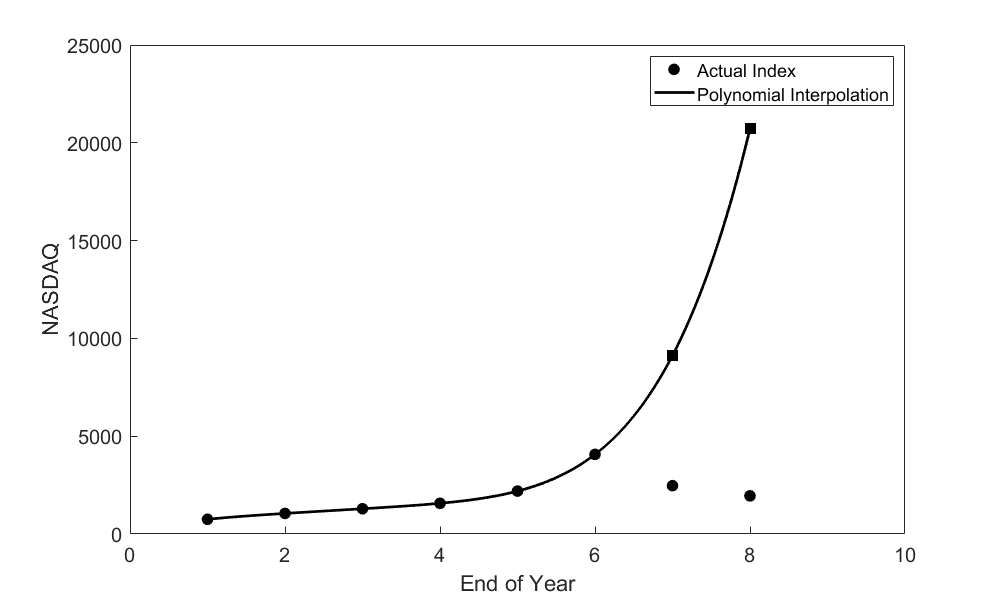

Kaw: “Right again, but look what you would’ve hoped for if you had depended on that trend continuing (Figure 1).”

Student: “So you’re saying that …?”

Kaw: “You should seldom depend on extrapolation as a source of approximation! Just take a look at how wrong you would have been (Table 2).”

| End of year | NASDAQ |

|---|---|

| \(1\) | \(751.96\) |

| \(2\) | \(1052.13\) |

| \(3\) | \(1291.03\) |

| \(4\) | \(1570.35\) |

| \(5\) | \(2192.69\) |

| \(6\) | \(4069.31\) |

Note: The range of years in Table 1 are actually between 1994 (Year 1) and 1999 (Year 9). Numbers start from 1 to avoid round-off errors and near singularities in matrix calculations.

| End of Year | Actual | Fifth order polynomial interpolation | Absolute relative true error |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(2000\) | \(2471\) | \(9128\) | \(269.47 \%\) |

| \(2001\) | \(1950\) | \(20720\) | \(962.36 \%\) |

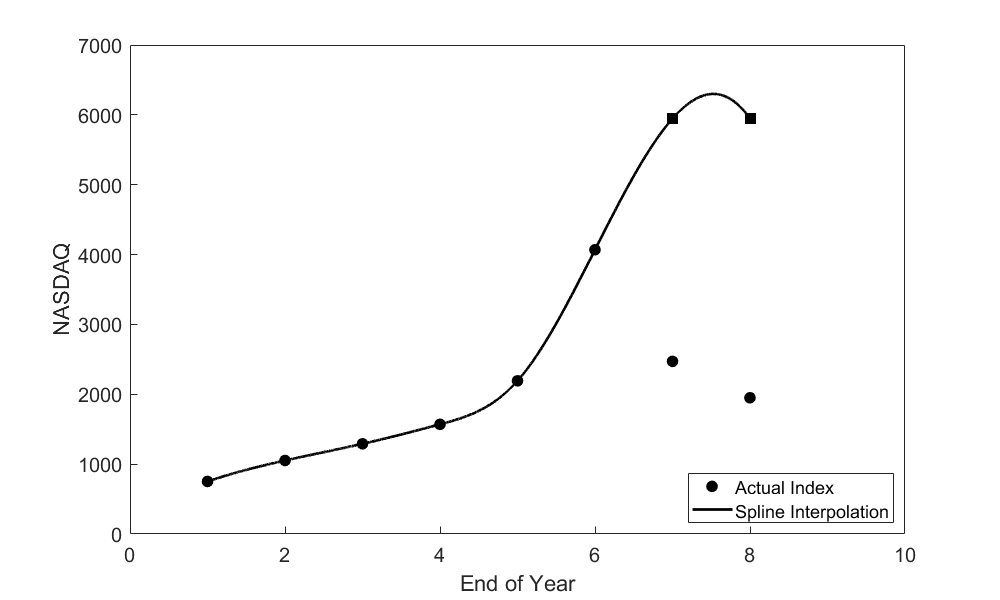

Student: “Now wait a sec! I wouldn’t have been quite that wrong. What if I had used cubic splines instead of a fifth-order interpolant?”

Kaw: “Let’s find out.”

| End of Year | Actual | Cubic spline interpolation | Absolute relative true error |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(2000\) | \(2471\) | \(5945.9\) | \(140.63 \%\) |

| \(2001\) | \(1950\) | \(5947.4\) | \(204.99 \%\) |

Student: “There you go. That didn’t take so long (Figure \(\PageIndex{1.2}\) and Table \(\PageIndex{1.3}\)).”

Kaw: “Well, let’s think about what this data means. If you had gone ahead and invested, thinking your projected yield would follow the spline, you would have only been 205% (Table \(\PageIndex{1.3}\)) wrong, as opposed to being 962% (Table \(\PageIndex{1.2}\)) wrong by following the polynomial. That’s not so bad, is it?”

Student: “Okay, you’ve got a point. Maybe I’ll hold off on being an investor and just use the cell phone.”

Kaw: “You’ve got a point, too—you’re brighter than you look … that is, if you turn off the phone before coming to class.”

* * * * *

<One year later … July 2002>

Student: “Hey, Dr. Kaw! Whatcha got for me today?”

Kaw: “The Computational Methods students just took their interpolation test today, so here you go. <hands stack of tests to student> Time to grade them!”

Student: <Grunt!> “That’s a lot of paper! Boy, interpolation … learned that a while ago.”

Kaw: “You haven’t forgotten my lesson to you about not extrapolating, have you?”

Student: “Of course not! Haven’t you seen the news? WorldCom just closed down 93% from 83¢ on June 25 to 6¢ per share! They’ve had to recalculate their earnings, so your skepticism really must’ve spread. Did you have an “in” on what was going on?”

Kaw: “Oh, of course not. I’m just an ignorant numerical methods professor.”