10.2: Slopes in Polar Coordinates

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

When we describe a curve using polar coordinates, it is still a curve in thex−y plane. We would like to be able to compute slopes and areas for these curves using polar coordinates.

We have seen that x=rcosθ and y=rsinθ describe the relationship between polar and rectangular coordinates. If in turn we are interested in a curve given by r=f(θ), then we can write x=f(θ)cosθ and y=f(θ)sinθ, describing x and y in terms of θ alone. The first of these equations describes θ implicitly in terms of x, so using the chain rule we may compute

dydx=dydθdθdx.

Since dθ/dx=1/(dx/dθ), we can instead compute

dydx=dy/dθdx/dθ=f(θ)cosθ+f′(θ)sinθ−f(θ)sinθ+f′(θ)cosθ.

Find the points at which the curve given by r=1+cosθ has a vertical or horizontal tangent line. Since this function has period 2π, we may restrict our attention to the interval [0,2π) or (−π,π], as convenience dictates. First, we compute the slope:

dydx=(1+cosθ)cosθ−sinθsinθ−(1+cosθ)sinθ−sinθcosθ=cosθ+cos2θ−sin2θ−sinθ−2sinθcosθ.

This fraction is zero when the numerator is zero (and the denominator is not zero). The numerator is 2cos2θ+cosθ−1 so by the quadratic formula cosθ=−1±√1+4⋅24=−1or12. This means θ is π or ±π/3. However, when θ=π, the denominator is also 0, so we cannot conclude that the tangent line is horizontal.

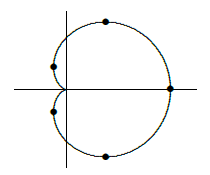

Setting the denominator to zero we get −θ−2sinθcosθ=0sinθ(1+2cosθ)=0, so either sinθ=0 or cosθ=−1/2. The first is true when θ is 0 or π, the second when θ)is\(2π/3 or 4π/3. However, as above, when θ=π, the numerator is also 0, so we cannot conclude that the tangent line is vertical. Figure 10.2.1 shows points corresponding to θ equal to 0, ±π/3, 2π/3 and 4π/3 on the graph of the function. Note that when θ=π the curve hits the origin and does not have a tangent line.

We know that the second derivative f″(x) is useful in describing functions, namely, in describing concavity. We can compute f″(x) in terms of polar coordinates as well. We already know how to write dy/dx=y′ in terms of θ, then

ddxdydx=dy′dx=dy′dθdθdx=dy′/dθdx/dθ.