16.3: Rings

- Page ID

- 81159

A nonempty set \(R\) is a ring if it has two closed binary operations, addition and multiplication, satisfying the following conditions.

- \(a + b = b + a\) for \(a, b \in R\text{.}\)

- \((a + b) + c = a + ( b + c)\) for \(a, b, c \in R\text{.}\)

- There is an element \(0\) in \(R\) such that \(a + 0 = a\) for all \(a \in R\text{.}\)

- For every element \(a \in R\text{,}\) there exists an element \(-a\) in \(R\) such that \(a + (-a) = 0\text{.}\)

- \((ab) c = a ( b c)\) for \(a, b, c \in R\text{.}\)

- For \(a, b, c \in R\text{,}\)

\begin{align*} a( b + c)&= ab +ac\\ (a + b)c & = ac + bc\text{.} \end{align*}

This last condition, the distributive axiom, relates the binary operations of addition and multiplication. Notice that the first four axioms simply require that a ring be an abelian group under addition, so we could also have defined a ring to be an abelian group \((R, +)\) together with a second binary operation satisfying the fifth and sixth conditions given above.

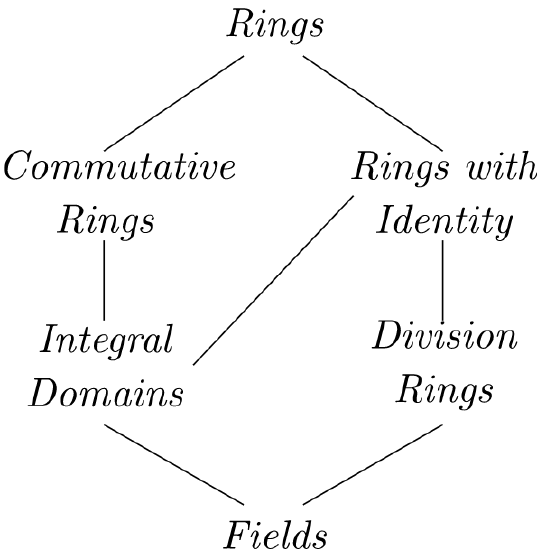

If there is an element \(1 \in R\) such that \(1 \neq 0\) and \(1a = a1 = a\) for each element \(a \in R\text{,}\) we say that \(R\) is a ring with unity or identity. A ring \(R\) for which \(ab = ba\) for all \(a, b\) in \(R\) is called a commutative ring. A commutative ring \(R\) with identity is called an integral domain if, for every \(a, b \in R\) such that \(ab = 0\text{,}\) either \(a = 0\) or \(b = 0\text{.}\) A division ring is a ring \(R\text{,}\) with an identity, in which every nonzero element in \(R\) is a unit; that is, for each \(a \in R\) with \(a \neq 0\text{,}\) there exists a unique element \(a^{-1}\) such that \(a^{-1} a = a a^{-1} = 1\text{.}\) A commutative division ring is called a field. The relationship among rings, integral domains, division rings, and fields is shown in Figure \(16.1\).

\(Figure \text { } 16.1.\) Types of rings

Example \(16.2\)

As we have mentioned previously, the integers form a ring. In fact, \({\mathbb Z}\) is an integral domain. Certainly if \(a b = 0\) for two integers \(a\) and \(b\text{,}\) either \(a=0\) or \(b=0\text{.}\)

Solution

However, \({\mathbb Z}\) is not a field. There is no integer that is the multiplicative inverse of \(2\text{,}\) since \(1/2\) is not an integer. The only integers with multiplicative inverses are \(1\) and \(-1\text{.}\)

Example \(16.3\)

Under the ordinary operations of addition and multiplication, all of the familiar number systems are rings:

Solution

the rationals, \({\mathbb Q}\text{;}\) the real numbers, \({\mathbb R}\text{;}\) and the complex numbers, \({\mathbb C}\text{.}\) Each of these rings is a field.

Example \(16.4\)

We can define the product of two elements \(a\) and \(b\) in \({\mathbb Z}_n\) by \(ab \pmod{n}\text{.}\)

Solution

For instance, in \({\mathbb Z}_{12}\text{,}\) \(5 \cdot 7 \equiv 11 \pmod{12}\text{.}\) This product makes the abelian group \({\mathbb Z}_n\) into a ring. Certainly \({\mathbb Z}_n\) is a commutative ring; however, it may fail to be an integral domain. If we consider \(3 \cdot 4 \equiv 0 \pmod{12}\) in \({\mathbb Z}_{12}\text{,}\) it is easy to see that a product of two nonzero elements in the ring can be equal to zero.

A nonzero element \(a\) in a commutative ring \(R\) is called a zero divisor if there is a nonzero element \(b\) in \(R\) such that \(ab = 0\text{.}\) In the previous example, \(3\) and \(4\) are zero divisors in \({\mathbb Z}_{12}\text{.}\)

Example \(16.5\)

In calculus the continuous real-valued functions on an interval \([a,b]\) form a commutative ring. We add or multiply two functions by adding or multiplying the values of the functions. If \(f(x) = x^2\) and \(g(x) = \cos x\text{,}\)

Solution

then \((f+g)(x) = f(x) + g(x) = x^2 + \cos x\) and \((fg)(x) = f(x) g(x) = x^2 \cos x\text{.}\)

Example \(16.6\)

The \(2 \times 2\) matrices with entries in \({\mathbb R}\) form a ring under the usual operations of matrix addition and multiplication.

Solution

This ring is noncommutative, since it is usually the case that \(AB \neq BA\text{.}\) Also, notice that we can have \(AB = 0\) when neither \(A\) nor \(B\) is zero.

Example \(16.7\)

For an example of a noncommutative division ring, let

\[ 1 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}, \quad {\mathbf i} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ -1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \quad {\mathbf j} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & i \\ i & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \quad {\mathbf k} = \begin{pmatrix} i & 0 \\ 0 & -i \end{pmatrix}\text{,} \nonumber \]

where \(i^2 = -1\text{.}\) These elements satisfy the following relations:

\begin{align*} {\mathbf i}^2 = {\mathbf j}^2 & = {\mathbf k}^2 = -1\\ {\mathbf i} {\mathbf j} & = {\mathbf k}\\ {\mathbf j} {\mathbf k} & = {\mathbf i}\\ {\mathbf k} {\mathbf i} & = {\mathbf j}\\ {\mathbf j} {\mathbf i} & = - {\mathbf k}\\ {\mathbf k} {\mathbf j} & = - {\mathbf i}\\ {\mathbf i} {\mathbf k} & = - {\mathbf j}\text{.} \end{align*}

Let \({\mathbb H}\) consist of elements of the form \(a + b {\mathbf i} + c {\mathbf j} +d {\mathbf k}\text{,}\) where \(a, b , c, d\) are real numbers. Equivalently, \({\mathbb H}\) can be considered to be the set of all \(2 \times 2\) matrices of the form

\[ \begin{pmatrix} \alpha & \beta \\ -\overline{\beta} & \overline{\alpha } \end{pmatrix}\text{,} \nonumber \]

where \(\alpha = a + di\) and \(\beta = b + ci\) are complex numbers. We can define addition and multiplication on \({\mathbb H}\) either by the usual matrix operations or in terms of the generators \(1\text{,}\) \({\mathbf i}\text{,}\) \({\mathbf j}\text{,}\) and \({\mathbf k}\text{:}\)

\begin{gather*} (a_1 + b_1 {\mathbf i} + c_1 {\mathbf j} +d_1 {\mathbf k} ) + ( a_2 + b_2 {\mathbf i} + c_2 {\mathbf j} +d_2 {\mathbf k} )\\ = (a_1 + a_2) + ( b_1 + b_2) {\mathbf i} + ( c_1 + c_2) \mathbf j + (d_1 + d_2) \mathbf k \end{gather*}

and

\[ (a_1 + b_1 {\mathbf i} + c_1 {\mathbf j} +d_1 {\mathbf k} ) ( a_2 + b_2 {\mathbf i} + c_2 {\mathbf j} +d_2 {\mathbf k} ) = \alpha + \beta {\mathbf i} + \gamma {\mathbf j} + \delta {\mathbf k}\text{,} \nonumber \]

where

\begin{align*} \alpha & = a_1 a_2 - b_1 b_2 - c_1 c_2 -d_1 d_2\\ \beta & = a_1 b_2 + a_2 b_1 + c_1 d_2 - d_1 c_2\\ \gamma & = a_1 c_2 - b_1 d_2 + c_1 a_2 + d_1 b_2\\ \delta & = a_1 d_2 + b_1 c_2 - c_1 b_2 + d_1 a_2\text{.} \end{align*}

Solution

Though multiplication looks complicated, it is actually a straightforward computation if we remember that we just add and multiply elements in \({\mathbb H}\) like polynomials and keep in mind the relationships between the generators \({\mathbf i}\text{,}\) \({\mathbf j}\text{,}\) and \({\mathbf k}\text{.}\) The ring \({\mathbb H}\) is called the ring of quaternions.

To show that the quaternions are a division ring, we must be able to find an inverse for each nonzero element. Notice that

\[ ( a + b {\mathbf i} + c {\mathbf j} + d {\mathbf k} )( a - b {\mathbf i} - c {\mathbf j} - d {\mathbf k} ) = a^2 + b^2 + c^2 + d^2\text{.} \nonumber \]

This element can be zero only if \(a\text{,}\) \(b\text{,}\) \(c\text{,}\) and \(d\) are all zero. So if \(a + b {\mathbf i} + c {\mathbf j} +d {\mathbf k} \neq 0\text{,}\)

\[ (a + b {\mathbf i} + c {\mathbf j} + d {\mathbf k})\left( \frac{a - b {\mathbf i} - c {\mathbf j} - d {\mathbf k} }{a^2 + b^2 + c^2 + d^2} \right) = 1\text{.} \nonumber \]

Proposition \(16.8\)

Let \(R\) be a ring with \(a, b \in R\text{.}\) Then

- \(a0 = 0a = 0\text{;}\)

- \(a(-b) = (-a)b = -ab\text{;}\)

- \((-a)(-b) =ab\text{.}\)

- Proof

-

To prove (1), observe that

\[ a0 = a(0+0)= a0+ a0; \nonumber \]

hence, \(a0=0\text{.}\) Similarly, \(0a = 0\text{.}\) For (2), we have \(ab + a(-b) = a(b-b) = a0 = 0\text{;}\) consequently, \(-ab = a(-b)\text{.}\) Similarly, \(-ab = (-a)b\text{.}\) Part (3) follows directly from (2) since \((-a)(-b) = -(a(- b)) = -(-ab) = ab\text{.}\)

Just as we have subgroups of groups, we have an analogous class of substructures for rings. A subring \(S\) of a ring \(R\) is a subset \(S\) of \(R\) such that \(S\) is also a ring under the inherited operations from \(R\text{.}\)

Example \(16.9\)

The ring \(n {\mathbb Z}\) is a subring of \({\mathbb Z}\text{.}\)

Solution

Notice that even though the original ring may have an identity, we do not require that its subring have an identity. We have the following chain of subrings:

\[ {\mathbb Z} \subset {\mathbb Q} \subset {\mathbb R} \subset {\mathbb C}\text{.} \nonumber \]

The following proposition gives us some easy criteria for determining whether or not a subset of a ring is indeed a subring. (We will leave the proof of this proposition as an exercise.)

Proposition \(16.10\)

Let \(R\) be a ring and \(S\) a subset of \(R\text{.}\) Then \(S\) is a subring of \(R\) if and only if the following conditions are satisfied.

- \(S \neq \emptyset\text{.}\)

- \(rs \in S\) for all \(r, s \in S\text{.}\)

- \(r-s \in S\) for all \(r, s \in S\text{.}\)

Example \(16.11\)

Let \(R ={\mathbb M}_2( {\mathbb R} )\) be the ring of \(2 \times 2\) matrices with entries in \({\mathbb R}\text{.}\) If \(T\) is the set of upper triangular matrices in \(R\text{;}\) i.e.,

\[ T = \left\{ \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ 0 & c \end{pmatrix} : a, b, c \in {\mathbb R} \right\}\text{,} \nonumber \]

Solution

then \(T\) is a subring of \(R\text{.}\) If

\[ A = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ 0 & c \end{pmatrix} \quad \text{and} \quad B = \begin{pmatrix} a' & b' \\ 0 & c' \end{pmatrix} \nonumber \]

are in \(T\text{,}\) then clearly \(A-B\) is also in \(T\text{.}\) Also,

\[ AB = \begin{pmatrix} a a' & ab' + bc' \\ 0 & cc' \end{pmatrix} \nonumber \]

is in \(T\text{.}\)