3.6: Determinants and Cramer’s Rule

- Page ID

- 6245

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Calculate the determinant of a \(2\times 2\) matrix.

- Use Cramer's rule to solve systems of linear equations with two variables.

- Calculate the determinant of a \(3\times 3\) matrix.

- Use Cramer's rule to solve systems of linear equations with three variables.

Linear Systems of Two Variables and Cramer's Rule

Recall that a matrix is a rectangular array of numbers consisting of rows and columns. We classify matrices by the number of rows \(n\) and the number of columns \(m\). For example, a \(3\times 4\) matrix, read “3 by 4 matrix,” is one that consists of \(3\) rows and \(4\) columns. A square matrix29 is a matrix where the number of rows is the same as the number of columns. In this section we outline another method for solving linear systems using special properties of square matrices. We begin by considering the following \(2\times 2\) coefficient matrix \(A\),

\(A = \left[ \begin{array} { c c} { a _ { 1 }} &{ b _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 }} &{ b _ { 2 } } \end{array} \right]\)

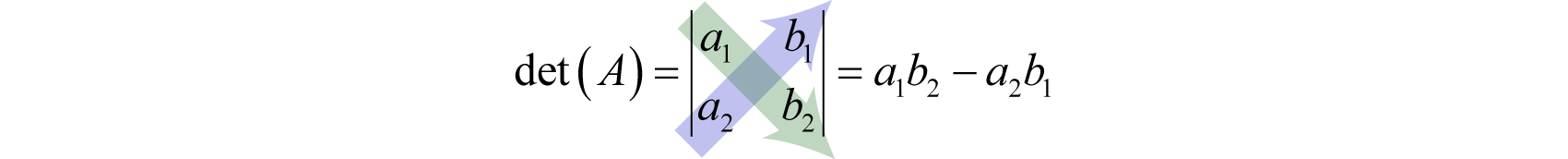

The determinant30 of a \(2\times 2\) matrix, denoted with vertical lines \(|A|\), or more compactly as det(A), is defined as follows:

The determinant is a real number that is obtained by subtracting the products of the values on the diagonal.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Calculate: \(\left| \begin{array} { l } { 3 - 5 } \\ { 2 - 2 } \end{array} \right|\)

Solution

The vertical line on either side of the matrix indicates that we need to calculate the determinant

\(\begin{aligned} \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 3} &{ - 5 } \\ { 2} &{ - 2 } \end{array} \right| & = 3 ( - 2 ) - 2 ( - 5 ) \\ & = - 6 + 10 \\ & = 4 \end{aligned}\)

Answer:

\(4\)

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\):

Calculate: \(\left| \begin{array} { c c } { - 6} &{4 } \\ { 0 } & {3}\end{array} \right]\)

Solution

Notice that the matrix is given in upper triangular form.

\(\begin{aligned} \left| \begin{array} { c c } { - 6} &{4 } \\ { 0} &{3 } \end{array} \right| & = - 6 ( 3 ) - 4 ( 0 ) \\ & = - 18 - 0 \\ & = - 18 \end{aligned}\)

Answer:

\(-18\)

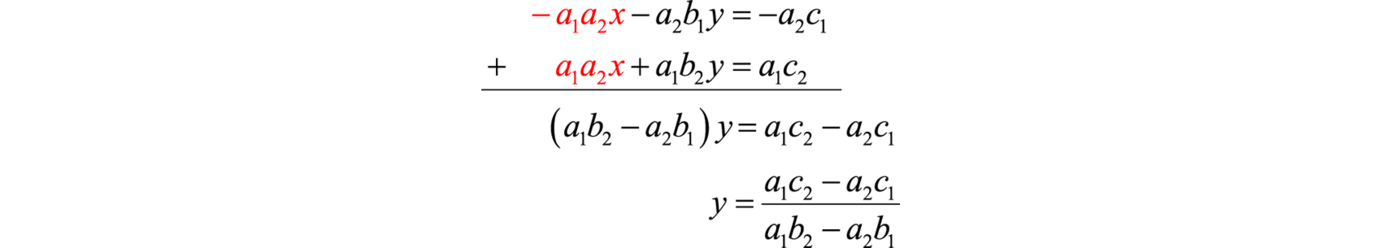

We can solve linear systems with two variables using determinants. We begin with a general \(2\times 2\) linear system and solve for \(y\). To eliminate the variable \(x\), multiply the first equation by \(−a_{2}\) and the second equation by \(a_{1}\).

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { l l } { a _ { 1 } x + b _ { 1 } y = c _ { 1 } } & { \stackrel { \times \left( - a _ { 2 } \right) } { \Longrightarrow } } \\ { a _ { 2 } x + b _ { 2 } y = c _ { 2 } } & { \underset { \times a _ { 1 } } { \Longrightarrow }} \end{array} \right. \left\{ \begin{array} { c } { - a _ { 1 } a _ { 2 } x - a _ { 2 } b _ { 1 } y = - a _ { 2 } c _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 1 } a _ { 2 } x + a _ { 1 } b _ { 2 } y = a _ { 1 } c _ { 2 } } \end{array} \right.\)

This results in an equivalent linear system where the variable \(x\) is lined up to eliminate. Now adding the equations we have

Both the numerator and denominator look very much like a determinant of a \(2\times 2\) matrix. In fact, this is the case. The denominator is the determinant of the coefficient matrix. And the numerator is the determinant of the matrix formed by replacing the column that represents the coefficients of \(y\) with the corresponding column of constants. This special matrix is denoted \(D_{y}\).

\(y = \frac{D_{y}}{D} =\frac{\left| \begin{array} { c c } { a _ { 1 }} &{\color{Cerulean}{ c _ { 1} } } \\ {\color{black}{ a _ { 2 }}} &{ \color{Cerulean}{c _ { 2} } } \end{array} \right|}{\left| \begin{array} { c c } { a _ { 1 }} &{ b _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 }}&{ b _ { 2 } } \end{array} \right|}= \frac { a _ { 1 } c _ { 2 } - a _ { 2 } c _ { 1 } } { a _ { 1 } b _ { 2 } - a _ { 2 } b _ { 1 } } \)

The value for \(x\) can be derived in a similar manner.

\(x = \frac{D_{x}}{D} =\frac{\left| \begin{array} { c c } { \color{Cerulean}{c _ { 1} }} &{ \color{black}{b _ { 1}} } \\ {\color{Cerulean}{ c _ { 2 }}} &{ \color{black}{b _ { 2} } } \end{array} \right|}{\left| \begin{array} { c c } { a _ { 1 }} &{ b _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 }}&{ b _ { 2 } } \end{array} \right|}= \frac { c _ { 1 } b _ { 2 } - c _ { 2 } b _ { 1 } } { a _ { 1 } b _ { 2 } - a _ { 2 } b _ { 1 } } \)

In general, we can form the augmented matrix as follows:

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { l l } { a _ { 1 } x + b _ { 1 } y = c _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 } x + b _ { 2 } y = c _ { 2 } } \end{array} \right. \Leftrightarrow \left[ \begin{array} { c c | c } { a _ { 1 }} &{ b _ { 1 }} &{\color{Cerulean}{c _ { 1}} } \\ { a _ { 2 }} &{ b _ { 2 }} &{ \color{Cerulean}{c _ { 2} } } \end{array} \right]\)

and then determine \(D, D_{x}\) and \(D_{y}\) by calculating the following determinants.

\(D = \left| \begin{array} { c c } { a _ { 1 }}&{ b _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 }}&{ b _ { 2 } } \end{array} \right| \quad D _ { x } = \left| \begin{array} { c c} { \color{Cerulean}{c _ { 1 }}}&{ \color{black}{b _ { 1} } } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{c _ { 2} }}&{ \color{black}{b _ { 2} } } \end{array} \right| \quad D _ { y } = \left| \begin{array} { c c} { a _ { 1 }}&{\color{Cerulean}{ c _ { 1} } } \\ { a _ { 2 }}&{\color{Cerulean}{ c _ { 2} } } \end{array} \right|\)

The solution to a system in terms of determinants described above, when D ≠ 0, is called Cramer’s rule31.

\(\begin{array} { c } { \color{Cerulean} { Cramer's\: Rule } } \\ { ( x , y ) = \left( \frac { D _ { x } } { D } , \frac { D _ { y } } { D } \right) } \end{array}\)

This theorem is named in honor of Gabriel Cramer (1704 - 1752).

The steps for solving a linear system with two variables using determinants (Cramer’s rule) are outlined in the following example.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\):

Solve using Cramer's rule: \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 2 x + y = 7 } \\ { 3 x - 2 y = - 7 } \end{array} \right.\).

Solution

Ensure the linear system is in standard form before beginning this process.

Step 1: Construct the augmented matrix and form the matrices used in Cramer’s rule.

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { c c } { 2 x + y = 7 } \\ { 3 x - 2 y = - 7 } \end{array} \right. \Rightarrow \left[ \begin{array} { c c |c } { 2 } & { 1 } & { \color{Cerulean}{7} } \\ { 3 } & { - 2 } & { \color{Cerulean}{- 7} } \end{array} \right]\)

In the square matrix used to determine \(D_{x}\), replace the first column of the coefficient matrix with the constants. In the square matrix used to determine \(D_{y}\), replace the second column with the constants.

\(D = \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 2 } & { 1 } \\ { 3 } & { - 2 } \end{array} \right| \quad D _ { x } = \left| \begin{array} { c c} { \color{Cerulean}{7} } & { \color{black}{1} } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{- 7} } & { \color{black}{- 2} } \end{array} \right| \quad D _ { y } = \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 2 } & {\color{Cerulean}{ 7} } \\ { 3 } & { \color{Cerulean}{- 7} } \end{array} \right|\)

Step 2: Calculate the determinants.

\(D _ { x } = \left| \begin{array} { r r } { 7 } & { 1 } \\ { - 7 } & { - 2 } \end{array} \right| = 7 ( - 2 ) - ( - 7 ) ( 1 ) = - 14 + 7 = - 7\)

\(D _ { y } = \left| \begin{array} { r r } { 2 } & { 7 } \\ { 3 } & { - 7 } \end{array} \right| = 2 ( - 7 ) - 3 ( 7 ) = - 14 - 21 = - 35\)

\(D = \left| \begin{array} { r r } { 2 } & { 1 } \\ { 3 } & { - 2 } \end{array} \right| = 2 ( - 2 ) - 3 ( 1 ) = - 4 - 3 = - 7\)

Step 3: Use Cramer's rule to calculate \(x\) and \(y\).

\(x = \frac { D _ { x } } { D } = \frac { - 7 } { - 7 } = 1 \quad \text { and } \quad y = \frac { D _ { y } } { D } = \frac { - 35 } { - 7 } = 5\)

Therefore the simultaneous solution \((x, y) = (1,5)\).

Step 4: : The check is optional; however, we do it here for the sake of completeness.

| \(\color{Cerulean}{Check\:\:}\color{YellowOrange}{(1,5)}\) | |

| Equation 1 | Equation 2 |

| \(\begin{array} { r } { 2 x + y = 7 } \\ { 2 ( \color{Cerulean}{1}\color{black}{ )} + ( \color{Cerulean}{5} \color{black}{)} = 7 } \\ { 2 + 5 = 7 } \\ { 7 = 7 } \color{Cerulean}{✓} \end{array}\) | \(\begin{array} { r } { 3 x - 2 y = - 7 } \\ { 3 ( \color{Cerulean}{1}\color{black}{ )} - 2 ( \color{Cerulean}{5}\color{black}{ )} = - 7 } \\ { 3 - 10 = - 7 } \\ { - 7 = - 7 } \color{Cerulean}{✓} \end{array}\) |

Answer:

\((1,5)\)

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\):

Solve using Cramer's rule: \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 3 x - y = - 2 } \\ { 6 x + 4 y = 2 } \end{array} \right.\).

Solution

The corresponding augmented coefficient matrix follows.

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 3 x - y = - 2 } \\ { 6 x + 4 y = 2 } \end{array} \right. \Rightarrow \left[ \begin{array} { c c |c } { 3 } & { - 1 } & { \color{Cerulean}{- 2} } \\ { 6 } & { 4 } & { \color{Cerulean}{2} } \end{array} \right]\)

And we have,

\(D _ { x } = \left| \begin{array} { r r } { \color{Cerulean}{- 2} } & { \color{black}{- 1} } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{2} } & {\color{black}{ 4} } \end{array} \right| = - 8 - ( - 2 ) = - 8 + 2 = - 6\)

\(D _ { y } = \left| \begin{array} { r r } { 3 } & { \color{Cerulean}{- 2} } \\ { 6 } & { \color{Cerulean}{2} } \end{array} \right| = 6 - ( - 12 ) = 6 + 12 = 18\)

\(D = \left| \begin{array} { r r } { 3 } & { - 1 } \\ { 6 } & { 4 } \end{array} \right| = 12 - ( - 6 ) = 12 + 6 = 18\)

Use Cramer’s rule to find the solution.

\(x = \frac { D _ { x } } { D } = \frac { - 6 } { 18 } = - \frac { 1 } { 3 } \quad \text { and } \quad y = \frac { D _ { y } } { D } = \frac { 18 } { 18 } = 1\)

Answer:

\((-\frac{1}{3}, 1)\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Solve using Cramer's rule: \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 5 x - 3 y = - 7 } \\ { - 7 x + 6 y = 11 } \end{array} \right.\).

- Answer

-

\((-1, \frac{2}{3})\)

www.youtube.com/v/TR3J8oCQZZY

When the determinant of the coefficient matrix \(D\) is zero, the formulas of Cramer’s rule are undefined. In this case, the system is either dependent or inconsistent depending on the values of \(D_{x}\) and \(D_{y}\). When \(D = 0\) and both \(D_{x} = 0\) and \(D_{y} = 0\) the system is dependent. When \(D = 0\) and either \(D_{x}\) or \(D_{y}\) is nonzero then the system is inconsistent.

\(\begin{array} { l } { \text { When } D = 0 } \\ { D _ { x } = 0 \text { and } D _ { y } = 0 \Rightarrow } \:\:\color{Cerulean}{Dependent\:System} \\ { D _ { x } \neq 0 \text { or } D _ { y } \neq 0 \:\:\:\Rightarrow } \:\:\color{Cerulean}{Inconsistent\:System}\end{array}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\):

Solve using Cramer's rule: \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { x + \frac { 1 } { 5 } y = 3 } \\ { 5 x + y = 15 } \end{array} \right.\).

Solution

The corresponding augmented matrix follows.

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { x + \frac { 1 } { 5 } y = 3 } \\ { 5 x + y = 15 } \end{array} \right. \Rightarrow \left[ \begin{array} { c c |c } { 1} &{ \frac { 1 } { 5 }}&{ \color{Cerulean}{3} } \\ { 5}&{1} &{ \color{Cerulean}{15} } \end{array} \right]\)

And we have the following.

\(D _ { x } = \left| \begin{array} { c c } {\color{Cerulean}{ 3}} &{\color{black}{ \frac { 1 } { 5} } } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{15} } & {\color{black}{ 1} } \end{array} \right| = 3 - 3 = 0\)

\(D _ { y } = \left| \begin{array} { l } { 1 } & { \color{Cerulean}{3} } \\ { 5 } & {\color{Cerulean}{ 15} } \end{array} \right| = 15 - 15 = 0\)

\(D = \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 1 } & { \frac { 1 } { 5 } } \\ { 5 } & { 1 } \end{array} \right| = 1 - 1 = 0\)

If we try to use Cramer's rule we have,

\(x = \frac { D _ { x } } { D } = \frac { 0 } { 0 } \quad \text { and } \quad y = \frac { D _ { y } } { D } = \frac { 0 } { 0 }\)

both of which are indeterminate quantities. Because \(D = 0\) and both \(D_{x} = 0\) and \(D_{y} = 0\) we know this is a dependent system. In fact, we can see that both equations represent the same line if we solve for \(y\).

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { x + \frac { 1 } { 5 } y = 3 } \\ { 5 x + y = 15 } \end{array} \right. \Rightarrow \left\{ \begin{array} { l } { y = - 5 x + 15 } \\ { y = - 5 x + 15 } \end{array} \right.\)

Therefore we can represent all solutions \((x, −5x + 15)\) where \(x\) is a real number.

Answer:

\(( x , - 5 x + 15 )\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Solve using Cramer's rule: \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 3 x - 2 y = 10 } \\ { 6 x - 4 y = 12 } \end{array} \right.\).

- Answer

-

\(\varnothing\)

www.youtube.com/v/D2lDCj321Nc

Linear Systems of Three Variables and Cramer's Rule

Consider the following \(3\times 3\) coefficient matrix \(A\),

\(A = \left[ \begin{array} { c c c } { a _ { 1 }} &{ b _ { 1 }}&{ c _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 }}&{ b _ { 2 }}&{ c _ { 2 } } \\ { a _ { 3 }}&{ b _ { 3 }}&{ c _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right]\)

The determinant of this matrix is defined as follows:

\(\operatorname { det } ( A ) = \left| \begin{array} { l l l } { a _ { 1 } } & { b _ { 1 } } & { c _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 } } & { b _ { 2 } } & { c _ { 2 } } \\ { a _ { 3 } } & { b _ { 3 } } & { c _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right| \\ = a _ { 1 } \left| \begin{array} { c c } { b _ { 2 } } & { c _ { 2 } } \\ { b _ { 3 } } & { c _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right| - b _ { 1 } \left| \begin{array} { c c } { a _ { 2 } } & { c _ { 2 } } \\ { a _ { 3 } } & { c _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right| + c _ { 1 } \left| \begin{array} { l l } { a _ { 2 } } & { b _ { 2 } } \\ { a _ { 3 } } & { b _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right| \\= a _ { 1 } \left( b _ { 2 } c _ { 3 } - b _ { 3 } c _ { 2 } \right) - b _ { 1 } \left( a _ { 2 } c _ { 3 } - a _ { 3 } c _ { 2 } \right) + c _ { 1 } \left( a _ { 2 } b _ { 3 } - a _ { 3 } b _ { 2 } \right)\)

Here each \(2\times 2\) determinant is called the minor32 of the preceding factor. Notice that the factors are the elements in the first row of the matrix and that they alternate in sign \((+ − +)\).

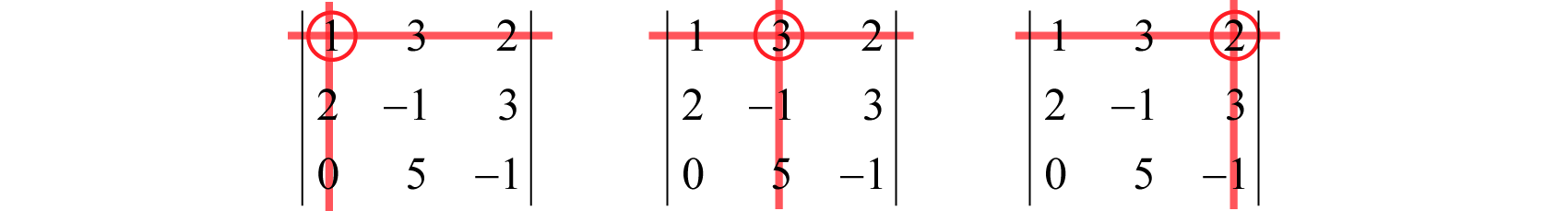

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\):

Calculate: \(\left| \begin{array} { r r r } { 1 } & { 3 } & { 2 } \\ { 2 } & { - 1 } & { 3 } \\ { 0 } & { 5 } & { - 1 } \end{array} \right|\)

Solution

To easily determine the minor of each factor in the first row we line out the first row and the corresponding column. The determinant of the matrix of elements that remain determines the corresponding minor.

Take care to alternate the sign of the factors in the first row. The expansion by minors about the first row follows:

\(\left| \begin{array} { r r r }\color{Cerulean}{ { 1 }} & \color{Cerulean}{ { 3 }} & \color{Cerulean}2 \\ {\color{black}{ 2} } & { - 1 } & { 3 } \\ { 0 } & { 5 } & { - 1 } \end{array} \right| = \color{Cerulean}{1}\color{black}{ \left| \begin{array} { r r } { - 1 } & { 3 } \\ { 5 } & { - 1 } \end{array} \right|} -\color{Cerulean}{ 3}\color{black}{ \left| \begin{array} { r r } { 2 } & { 3 } \\ { 0 } & { - 1 } \end{array} \right|} + \color{Cerulean}{2}\color{black}{ \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 2 } & { - 1 } \\ { 0 } & { 5 } \end{array} \right|} \\ \begin{array} { l } { = 1 ( 1 - 15 ) - 3 ( - 2 - 0 ) + 2 ( 10 - 0 ) } \\ { = 1 ( - 14 ) - 3 ( - 2 ) + 2 ( 10 ) } \\ { = - 14 + 6 + 20 } \\ { = 12 } \end{array}\)

Answer:

\(12\)

Expansion by minors can be performed about any row or any column. The sign of the coefficients, determined by the chosen row or column, will alternate according the following sign array.

\(\left[ \begin{array} { c } { + - + } \\ { - + - } \\ { + - + } \end{array} \right]\)

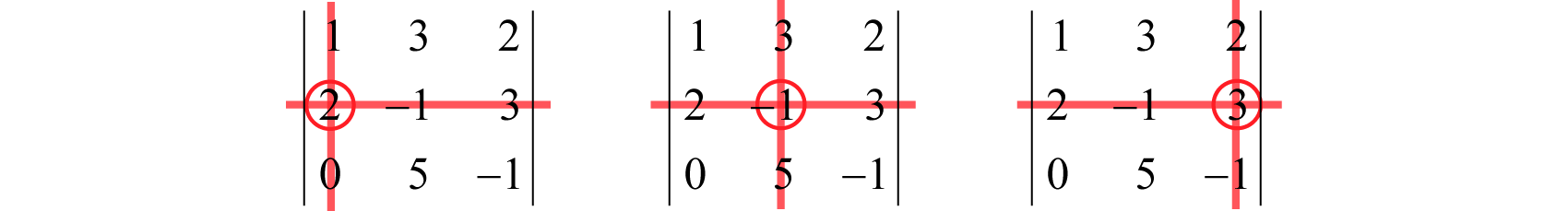

Therefore, to expand about the second row we will alternate the signs starting with the opposite of the first element. We can expand the previous example about the second row to show that the same answer for the determinant is obtained.

And we can write,

\(\left| \begin{array} { c c c } { 1 } & { 3 } & { 2 } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{2} } & {\color{Cerulean}{ - 1} } & { \color{Cerulean}{3} } \\ { \color{black}{0} } & { 5 } & { - 1 } \end{array} \right| = - ( \color{Cerulean}{2}\color{black}{ )} \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 3 } & { 2 } \\ { 5 } & { - 1 } \end{array} \right| + ( \color{Cerulean}{- 1}\color{black}{ )} \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 1 } & { 2 } \\ { 0 } & { - 1 } \end{array} \right| - ( \color{Cerulean}{3}\color{black}{ )} \left| \begin{array} { c } { 13 } \\ { 05 } \end{array} \right|\\ \begin{array} { l } { = - 2 ( - 3 - 10 ) - 1 ( - 1 - 0 ) - 3 ( 5 - 0 ) } \\ { = - 2 ( - 13 ) - 1 ( - 1 ) - 3 ( 5 ) } \\ { = 26 + 1 - 15 } \\ { = 12 } \end{array}\)

Note that we obtain the same answer \(12\).

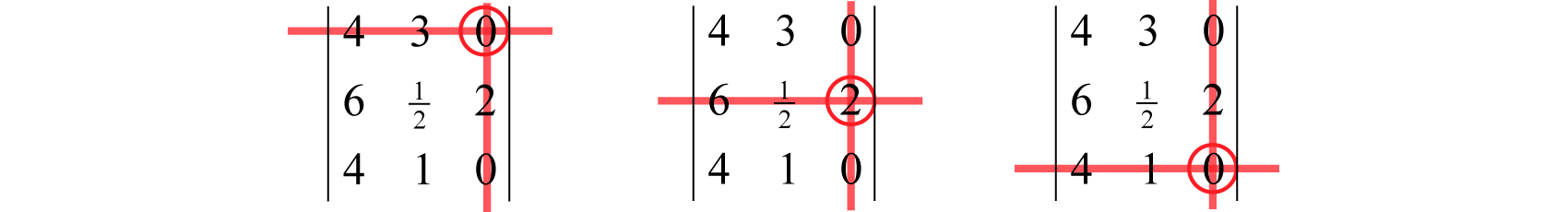

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\):

Calculate: \(\left| \begin{array} { c c c } { 4 } & { 3} &{0 } \\ { 6 } & { \frac { 1 } { 2 } } & { 2 } \\ { 4 } & { 1 } & { 0 } \end{array} \right|\)

Solution

The calculations are simplified if we expand about the third column because it contains two zeros.

The expansion by minors about the third column follows:

\(\left| \begin{array} { c c c } { 4 } & { 3} &{\color{Cerulean}{0} } \\ { 6 } & { \frac { 1 } { 2 } } & { \color{Cerulean}{2} } \\ { 4 } & { 1} &{\color{Cerulean}{0} } \end{array} \right| = \color{Cerulean}{0}\color{black}{ \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 6} &{ \frac { 1 } { 2 } } \\ { 4 } & { 1 } \end{array} \right|} - \color{Cerulean}{2}\color{black}{ \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 4} &{3 } \\ { 4} &{1 } \end{array} \right|} + \color{Cerulean}{0}\color{black}{ \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 4} &{3 } \\ { 6} &{ \frac { 1 } { 2 } } \end{array} \right|} \\ \begin{array} { l } { = 0 - 2 ( 4 - 12 ) + 0 } \\ { = - 2 ( - 8 ) } \\ { = 16 } \end{array}\)

Answer:

\(16\)

It should be noted that there are other techniques used for remembering how to calculate the determinant of a \(3\times 3\) matrix. In addition, many modern calculators and computer algebra systems can find the determinant of matrices. You are encouraged to research this rich topic.

We can solve linear systems with three variables using determinants. To do this, we begin with the augmented coefficient matrix,

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { a _ { 1 } x + b _ { 1 } y + c _ { 1 } z = d _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 } x + b _ { 2 } y + c _ { 2 } z = d _ { 2 } } \\ { a _ { 3 } x + b _ { 3 } y + c _ { 3 } z = d _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right. \Leftrightarrow \left[ \begin{array} { c c c | c } { a _ { 1 }} &{ b _ { 1 }} &{ c _ { 1 }} &{\color{Cerulean}{ d _ { 1} }} \\ { a _ { 2 }} &{ b _ { 2 }} &{ c _ { 2 }} & {\color{Cerulean}{d _ { 2} }} \\ { a _ { 3 }} &{ b _ { 3} }&{ c _ { 3} } &{\color{Cerulean}{d _ { 3}} } \end{array} \right]\)

Let \(D\) represent the determinant of the coefficient matrix,

\(D = \left| \begin{array} { c c c } { a _ { 1 }} &{ b _ { 1 } } &{c _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 }} &{ b _ { 2} }&{ c _ { 2 } } \\ { a _ { 3 }}&{ b _ { 3} }&{ c _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right|\)

Then determine \(D_{x}, D_{y}\), and \(D_{z}\) by calculating the following determinants.

\(D _ { x } = \left| \begin{array} { c c c } { \color{Cerulean}{d _ { 1 }}} &{\color{black}{ b _ { 1} }} &{ c _ { 1 } } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{d _ { 2} }} &{\color{Cerulean}{ b _ { 2} }} &{ c _ { 2 } } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{d _ { 3} }}&{\color{black}{ b _ { 3} }}&{ c _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right| D _ { y } = \left| \begin{array} { c c c } { a _ { 1 }} &{ \color{Cerulean}{d _ { 1} }}&{ \color{black}{c _ { 1} } } \\ { a _ { 2 }} &{ \color{Cerulean}{d _ { 2} }} &{ \color{black}{c _ { 2} } } \\ { a _ { 3 }} &{ \color{Cerulean}{d _ { 3} }}&{ \color{black}{c _ { 3} } } \end{array} \right| D _ { z } = \left| \begin{array} { c c c } { a _ { 1 }}&{ b _ { 1 }}&{\color{Cerulean}{ d _ { 1} } } \\ { a _ { 2 }}&{ b _ { 2 }}&{\color{Cerulean}{ d _ { 2 }} } \\ { a _ { 3 }}&{ b _ { 3 } }&{\color{Cerulean}{d _ { 3} } } \end{array} \right|\)

When \(D ≠ 0\), the solution to the system in terms of the determinants described above can be calculated using Cramer’s rule:

\(\begin{array} { c } { \color{Cerulean} { Cramer's\: Rule } } \\ { ( x , y , z ) = \left( \frac { D _ { x } } { D } , \frac { D _ { y } } { D } , \frac { D _ { z } } { D } \right) } \end{array}\)

Use this to efficiently solve systems with three variables.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Solve using Cramer's rule: \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 3 x + 7 y - 4 z = 0 } \\ { 2 x + 5 y - 3 z = 1 } \\ { - 5 x + 2 y + 4 z = 8 } \end{array} \right.\).

Solution

Begin by determining the corresponding augmented matrix.

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { c c } { 3 x + 7 y - 4 z = 0 } \\ { 2 x + 5 y - 3 z = 1 } \\ { - 5 x + 2 y + 4 z = 8 } \end{array} \right. \Leftrightarrow \left[ \begin{array} { c c | c } { 37}&{ - 4}&{\color{Cerulean}{0} } \\ { 25}&{ - 3}&{\color{Cerulean}{1} } \\ { - 52}&{4}&{\color{Cerulean}{8} } \end{array} \right]\)

Next, calculate the determinant of the coefficient matrix.

\(D = \left| \begin{array} { r r r } { \color{Cerulean}{3} } & { \color{Cerulean}{7} } & { \color{Cerulean}{- 4} } \\ { 2 } & { 5 } & { - 3 } \\ { - 5 } & { 2 } & { 4 } \end{array} \right| \\ = \color{Cerulean}{3} \color{black}{\left| \begin{array} { r r } { 5 } & { - 3 } \\ { 2 } & { 4 } \end{array} \right|} -\color{Cerulean}{ 7} \color{black}{\left| \begin{array} { c c } { 2 } & { - 3 } \\ { - 5 } & { 4 } \end{array} \right|} + ( \color{Cerulean}{- 4}\color{black}{ )} \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 2 } & { 5 } \\ { - 5 } & { 2 } \end{array} \right| \\ \begin{array} { l } { = 3 ( 20 - ( - 6 ) ) - 7 ( 8 - 15 ) - 4 ( 4 - ( - 25 ) ) } \\ { = 3 ( 26 ) - 7 ( - 7 ) - 4 ( 29 ) } \\ { = 78 + 49 - 116 } \\ { = 11 } \end{array}\)

Similarly we can calculate \(D_{x}, D_{y}\), and \(D_{z}\). This is left as an exercise.

\(D _ { x } = \left| \begin{array} { c c c } { \color{Cerulean}{0} } & { \color{black}{7} } & { - 4 } \\ {\color{Cerulean}{ 1} } & { \color{black}{5} } & { - 3 } \\ {\color{Cerulean}{ 8} } & { \color{black}{2} } & { 4 } \end{array} \right| = - 44\)

\(D _ { y } = \left| \begin{array} { r r r } { 3 } & { \color{Cerulean}{0} } & { \color{black}{- 4} } \\ { 2 } & {\color{Cerulean}{ 1} } & { \color{black}{- 3} } \\ { - 5 } & { \color{Cerulean}{8} } & { \color{black}{4} } \end{array} \right| = 0\)

\(D _ { z } = \left| \begin{array} { c c c } { 3 } & { 7 } & { \color{Cerulean}{0} } \\ { 2 } & { 5 } & { \color{Cerulean}{1} } \\ { - 5 } & { 2 } & { \color{Cerulean}{8} } \end{array} \right| = - 33\)

Using Cramer's rule we have,

\(x = \frac { D _ { x } } { D } = \frac { - 44 } { 11 } = - 4 \quad y = \frac { D _ { y } } { D } = \frac { 0 } { 11 } = 0 \quad z = \frac { D _ { z } } { D } = \frac { - 33 } { 11 } = - 3\)

Answer:

\((-4, 0, -3)\)

If the determinant of the coefficient matrix \(D = 0\), then the system is either dependent or inconsistent. This will depend on \(D_{x} , D_{y}\), and \(D_{z}\). If they are all zero, then the system is dependent. If at least one of these is nonzero, then it is inconsistent.

\(\begin{array} { l } { When\:\: D = 0 \text { , } } \\ { D _ { x } = 0 \text { and } D _ { y } = 0 \text { and } D _ { z } = 0 \Rightarrow \color{Cerulean} { Dependent\: System } } \\ { D _ { x } \neq 0 \text { or } D _ { y } \neq 0 \text { or } D _ { z } \neq 0 \Rightarrow \color{Cerulean} { Inconsistent \:System } } \end{array}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{9}\):

Solve using Cramer's rule: \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 4 x - y + 3 z = 5 } \\ { 21 x - 4 y + 18 z = 7 } \\ { - 9 x + y - 9 z = - 8 } \end{array} \right.\).

Solution

Begin by determining the corresponding augmented matrix.

\(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 4 x - y + 3 z = 5 } \\ { 21 x - 4 y + 18 z = 7 } \\ { - 9 x + y - 9 z = - 8 } \end{array} \right. \Leftrightarrow \left [ \begin{array}{c c c |c } {4}& {-1} &{3} &{\color{Cerulean}{5}} \\{21} &{-4} &{18}&{\color{Cerulean}{7}} \\{-9} &{1} &{-9} &{\color{Cerulean}{-8}} \end{array} \right ]\)

Next, determine the determinant of the coefficient matrix.

\(D = \left| \begin{array} { r r r } { \color{Cerulean}{4} } & { \color{Cerulean}{- 1} } & { \color{Cerulean}{3} } \\ { 21 } & { - 4 } & { 18 } \\ { - 9 } & { 1 } & { - 9 } \end{array} \right|\)

\(= \color{Cerulean}{4}\color{black}{ \left| \begin{array} { c c } { - 4 } & { 18 } \\ { 1 } & { - 9 } \end{array} \right|} - (\color{Cerulean}{ - 1}\color{black}{ )} \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 21 } & { 18 } \\ { - 9 } & { - 9 } \end{array} \right| + \color{Cerulean}{3}\color{black}{ \left| \begin{array} { c c } { 21 } & { - 4 } \\ { - 9 } & { 1 } \end{array} \right|}\)

\(\begin{array} { l } { = 4 ( 36 - 18 ) + 1 ( - 189 - ( - 162 ) ) + 3 ( 21 - 36 ) } \\ { = 4 ( 18 ) + 1 ( - 27 ) + 3 ( - 15 ) } \\ { = 72 - 27 - 45 } \\ { = 0 } \end{array}\)

Since \(D=0\), the system is either dependent or inconsistent.

\(D _ { x } = \left| \begin{array} { c c c} { \color{Cerulean}{5}}&{ \color{black}{- 1} } & { 3 } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{7}}&{ \color{black}{- 4} } & { 18 } \\ { \color{Cerulean}{- 8} } & { \color{black}{1}}&{ - 9 } \end{array} \right| = 96\)

However, because \(D_{x}\) is nonzero we conclude the system is inconsistent. There is no simultaneous solution.

Answer:

\(\varnothing\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Solve using Cramer's rule: \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 2 x + 6 y + 7 z = 4 } \\ { - 3 x - 4 y + 5 z = 12 } \\ { 5 x + 10 y - 3 z = - 13 } \end{array} \right.\).

- Answer

-

\((-3, \frac{1}{2}, 1)\)

www.youtube.com/v/NfFwHG8ojts

Key Takeaways

- The determinant of a matrix is a real number.

- The determinant of a \(2\times 2\) matrix is obtained by subtracting the product of the values on the diagonals.

- The determinant of a \(3\times 3\) matrix is obtained by expanding the matrix using minors about any row or column. When doing this, take care to use the sign array to help determine the sign of the coefficients.

- Use Cramer’s rule to efficiently determine solutions to linear systems.

- When the determinant of the coefficient matrix is \(0\), Cramer’s rule does not apply; the system will either be dependent or inconsistent.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Calculate the determinant.

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c } { 1}&{2 } \\ { 3}&{4 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c} { 5}&{3 } \\ { 2}&{4 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c } { - 1 } & { 3 } \\ { - 3 } & { - 2 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c } { 7 } & { 4 } \\ { 3 } & { - 2 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c} { - 4}&{1 } \\ { - 3}&{0 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c } { 9 } & { 5 } \\ { - 1 } & { 0 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c } { 1}&{0 } \\ { 5}&{0 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c } { 0}&{3 } \\ { 5}&{0 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c } { 0 } & { 4 } \\ { - 1 } & { 3 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { l l } { 10 } & { 2 } \\ { 10 } & { 2 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { l l } { a _ { 1 } } & { b _ { 1 } } \\ { 0 } & { b _ { 2 } } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { l l } { 0 } & { b _ { 1 } } \\ { a _ { 2 } }&{b _ { 2 } } \end{array} \right|\)

- Answer

-

1. \(-2\)

3. \(11\)

5. \(3\)

7. \(0\)

9. \(4\)

11. \(a_{1}b_{2}\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Solve using Cramer's rule.

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 3 x - 5 y = 8 } \\ { 2 x - 7 y = 9 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 2 x + 3 y = - 1 } \\ { 3 x + 4 y = - 2 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 2 x - y = - 3 } \\ { 4 x + 3 y = 4 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { x + 3 y = 1 } \\ { 5 x - 6 y = - 9 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { x + y = 1 } \\ { 6 x + 3 y = 2 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { x - y = - 1 } \\ { 5 x + 10 y = 4 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 5 x - 7 y = 14 } \\ { 4 x - 3 y = 6 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 9 x + 5 y = - 9 } \\ { 7 x + 2 y = - 7 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 6 x - 9 y = 3 } \\ { - 2 x + 3 y = 1 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 3 x - 9 y = 3 } \\ { 2 x - 6 y = 2 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} 4 x - 5 y & = 20 \\ 3 y & = - 9 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { x - y = 0 } \\ { 2 x - 3 y = 0 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 2 x + y = a } \\ { x + y = b } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} a x + y & = 0 \\ b y & = 1 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- Answer

-

1. \((1,-1)\)

3. \(\left( - \frac { 1 } { 2 } , 2 \right)\)

5. \(\left( - \frac { 1 } { 3 } , \frac { 4 } { 3 } \right)\)

7. \((0, -2)\)

9. \(\varnothing\)

11. \(\left( \frac { 5 } { 4 } , - 3 \right)\)

13. \(( a - b , 2 b - a )\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Calculate the determinant.

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c c } { 1}&{2}&{3 } \\ { 2}&{1}&{3 } \\ { 1}&{3}&{2 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c c } { 2}&{5}&{1 } \\ { 1}&{2}&{4 } \\ { 3}&{2}&{3 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { r r r } { - 3 } & { 1 } & { - 1 } \\ { 3 } & { - 1 } & { - 2 } \\ { - 2 } & { 5 } & { 1 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { r r r } { 1 } & { - 1 } & { 5 } \\ { - 4 } & { 5 } & { - 1 } \\ { - 1 } & { 2 } & { - 3 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { r r r } { 3 } & { - 1 } & { 2 } \\ { 2 } & { 3 } & { - 1 } \\ { 5 } & { 2 } & { 1 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { r r r } { 4 } & { 0 } & { - 3 } \\ { 3 } & { - 1 } & { 0 } \\ { 0 } & { - 5 } & { 2 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { r r r } { 0 } & { - 3 } & { 4 } \\ { - 3 } & { 0 } & { 6 } \\ { 0 } & { 2 } & { - 3 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c c } { 6 } & { - 1 } & { - 3 } \\ { 2 } & { 5 } & { 2 } \\ { 8 } & { 4 } & { - 1 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { c c c } { 2}&{5}&{7 } \\ { 0}&{3}&{5 } \\ { 0}&{0}&{4 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { l l l } { 2 } & { 10 } & { 9 } \\ { 0 } & { 3 } & { 13 } \\ { 0 } & { 0 } & { 4 } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { l l l } { a _ { 1 } } & { b _ { 1 }}&{ c _ { 1 } } \\ { 0}&{ b _ { 2 }}&{ c _ { 2 } } \\ { 0 } & { 0}&{ c _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right|\)

- \(\left| \begin{array} { l l l } { a _ { 1 } } & { 0 } & { 0 } \\ { a _ { 2 } } & { b _ { 2 } } & { 0 } \\ { a _ { 3 }}&{ b _ { 3 } } & { c _ { 3 } } \end{array} \right|\)

- Answer

-

1. \(6\)

3. \(-39\)

5. \(0\)

7. \(3\)

9. \(24\)

11. \(a_{1}b_{2}c_{3}\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Solve using Cramer's rule.

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { x - y + 2 z = - 3 } \\ { 3 x + 2 y - z = 13 } \\ { - 4 x - 3 y + z = - 18 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} 3 x + 4 y - z & = 10 \\ 4 x + 6 y + 7 z & = 9 \\ 2 x + 3 y + 5 z & = 3 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} 5 x + y - z & = 0 \\ 2 x - 2 y + z & = - 9 \\ - 6 x - 5 y + 3 z & = - 13 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { - 4 x + 5 y + 2 z = 12 } \\ { 3 x - y - z = - 2 } \\ { 5 x + 3 y - 2 z = 5 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} x - y + z & = - 1 \\ - 2 x + 4 y - 3 z & = 4 \\ 3 x - 3 y - 2 z & = 2 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 2 x + y - 4 z = 7 } \\ { 2 x - 3 y + 2 z = - 4 } \\ { 4 x - 5 y + 2 z = - 5 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 4 x + 3 y - 2 z = 2 } \\ { 2 x + 5 y + 8 z = - 1 } \\ { x - y - 5 z = 3 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { x - y + z = 7 } \\ { x + 2 y + z = 1 } \\ { x - 2 y - 2 z = 9 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 3 x - 6 y + 2 z = 12 } \\ { - 5 x - 2 y + 3 z = 4 } \\ { 7 x + 3 y - 4 z = - 6 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 2 x - y - 5 z = 2 } \\ { 3 x + 2 y - 4 z = - 3 } \\ { 5 x + y - 9 z = 4 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { 4 x + 3 y - 4 z = - 13 } \\ { 2 x + 6 y - 5 z = - 2 } \\ { - 2 x - 3 y + 3 z = 5 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} x - 2 y + z & = - 1 \\ 4 y - 3 z & = 0 \\ 3 y - 2 z & = 1 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} 2 x + 3 y - z & = - 5 \\ x + 2 y & = 0 \\ 3 x + 10 y & = 4 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 2 x - 3 y - 2 y = 9 } \\ { - 3 x + 4 y + 4 z = - 13 } \\ { x - y - 2 z = 4 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 2 x + y - 2 z = - 1 } \\ { x - y + 3 z = 2 } \\ { 3 x + y - z = 1 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} 3 x - 8 y + 9 z & = - 2 \\ - x + 5 y - 10 z & = 3 \\ x - 3 y + 4 z & = - 1 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} 5 x - 6 y + 3 z & = 2 \\ 3 x - 4 y + 2 z & = 0 \\ 2 x - 2 y + z & = 0 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { 5 x + 10 y - 4 z = 12 } \\ { 2 x + 5 y + 4 z = 0 } \\ { x + 5 y - 8 z = 6 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{aligned} 5 x + 6 y + 7 z & = 2 \\ 2 y + 3 z & = 3 \\ 4 z & = 4 \end{aligned} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { x + 2 z = - 1 } \\ { - 5 y + 3 z = 10 } \\ { 4 x - 3 y = 2 } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { l } { x + y + z = a } \\ { x + 2 y + 2 z = a + b } \\ { x + 2 y + 3 z = a + b + c } \end{array} \right.\)

- \(\left\{ \begin{array} { c } { x + y + z = a + b + c } \\ { x + 2 y + 2 z = a + 2 b + 2 c } \\ { x + y + 2 z = a + b + 2 c } \end{array} \right.\)

- Answer

-

1. \((2, 3, -1)\)

3. \((-1, 2, -3)\)

5. \(\left( \frac { 1 } { 2 } , \frac { 1 } { 2 } , - 1 \right)\)

7. \((0, -2, 0)\)

9. \(\left( \frac { 1 } { 2 } z - 4 , \frac { 2 } { 3 } z + 1 , z \right)\)

11. \((-2, 1, 4)\)

13. \(\left( - \frac { 1 } { 2 } , 5 , \frac { 5 } { 2 } \right)\)

15. \(\varnothing\)

17. \((-1, 0, 1)\)

19. \(( a - b , b - c , c )\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{8}\)

- Research and discuss the history of the determinant. Who is credited for first introducing the notation of a determinant?

- Research other ways in which we can calculate the determinant of a \(3 \times 3\) matrix. Give an example

- Answer

-

1. Answer may vary

Footnotes

29A matrix with the same number of rows and columns.

30A real number associated with a square matrix.

31The solution to an independent system of linear equations expressed in terms of determinants.

32The determinant of the matrix that results after eliminating a row and column of a square matrix.