10.4: Evaluate and Graph Logarithmic Functions

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Convert between exponential and logarithmic form

- Evaluate logarithmic functions

- Graph Logarithmic functions

- Solve logarithmic equations

- Use logarithmic models in applications

Before you get started, take this readiness quiz.

- Solve: x2=81.

If you missed this problem, review Example 6.46. - Evaluate: 3−2.

If you missed this problem, review Example 5.15. - Solve: 24=3x−5.

If you missed this problem, review Example 2.2.

We have spent some time finding the inverse of many functions. It works well to ‘undo’ an operation with another operation. Subtracting ‘undoes’ addition, multiplication ‘undoes’ division, taking the square root ‘undoes’ squaring.

As we studied the exponential function, we saw that it is one-to-one as its graphs pass the horizontal line test. This means an exponential function does have an inverse. If we try our algebraic method for finding an inverse, we run into a problem.

f(x)=ax

Rewrite with y=f(x).

y=ax

Interchange the variables x and y.

x=ay

Solve for y.

Oops! We have no way to solve for y!

To deal with this we define the logarithm function with base a to be the inverse of the exponential function f(x)=ax. We use the notation f−1(x)=logax and say the inverse function of the exponential function is the logarithmic function.

The function f(x)=logax is the logarithmic function with base a, where a>0,x>0, and a≠1.

y=logax is equivalent to x=ay

Convert Between Exponential and Logarithmic Form

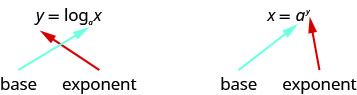

Since the equations y=logax and x=ay are equivalent, we can go back and forth between them. This will often be the method to solve some exponential and logarithmic equations. To help with converting back and forth let’s take a close look at the equations. See Figure 10.3.1. Notice the positions of the exponent and base.

If we realize the logarithm is the exponent it makes the conversion easier. You may want to repeat, “base to the exponent give us the number.”

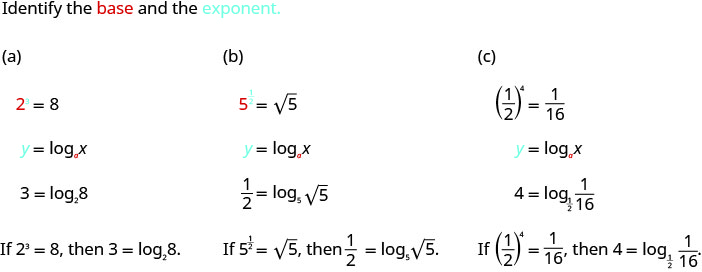

Convert to logarithmic form:

- 23=8

- 512=√5

- (12)x=116

Solution:

Convert to logarithmic form:

- 32=9

- 712=√7

- (13)x=127

- Answer

-

- log39=2

- log7√7=12

- log13127=x

Convert to logarithmic form:

- 43=64

- 413=3√4

- (12)x=132

- Answer

-

- log464=3

- log43√4=13

- log12132=x

In the next example we do the reverse—convert logarithmic form to exponential form.

Convert to exponential form:

- 2=log864

- 0=log41

- −3=log1011000

Solution:

Convert to exponential form:

- 3=log464

- 0=logx1

- −2=log101100

- Answer

-

- 64=43

- 1=x0

- 1100=10−2

Convert to exponential form:

- 3=log327

- 0=logx1

- −1=log10110

- Answer

-

- 27=33

- 1=x0

- 110=10−1

Evaluate Logarithmic Functions

We can solve and evaluate logarithmic equations by using the technique of converting the equation to its equivalent exponential equation.

Find the value of x:

- logx36=2

- log4x=3

- log1218=x

Solution:

a.

logx36=2

Convert to exponential form.

x2=36

Solve the quadratic.

x=6,x=−6

The base of a logarithmic function must be positive, so we eliminate x=−6.

x=6 Therefore, log636=2

b.

log4x=3

Convert to exponential form.

43=x

Simplify.

x=64 Therefore ,log464=3

c.

log1218=x

Convert to exponential form.

(12)x=18

Rewrite 18 as (12)3.

(12)x=(12)3

With the same base, the exponents must be equal.

x=3 Therefore log1218=3

Find the value of x:

- logx64=2

- log5x=3

- log1214=x

- Answer

-

- x=8

- x=125

- x=2

Find the value of x:

- logx81=2

- log3x=5

- log13127=x

- Answer

-

- x=9

- x=243

- x=3

When see an expression such as log327, we can find its exact value two ways. By inspection we realize it means “3 to what power will be 27”? Since 33=27, we know log327=3. An alternate way is to set the expression equal to x and then convert it into an exponential equation.

Find the exact value of each logarithm without using a calculator:

- log525

- log93

- log2116

Solution:

a.

log525

5 to what power will be 25?

log525=2

Or

Set the expression equal to x.

log525=x

Change to exponential form.

5x=25

Rewrite 25 as 52.

5x=52

With the same base the exponents must be equal.

x=2 Therefore ,log525=2.

b.

log93

Set the expression equal to x.

log93=x

Change to exponential form.

9x=3

Rewrite 9 as 32.

(32)x=31

Simplify the exponents.

32x=31

With the same base the exponents must be equal.

2x=1

Solve the equation.

x=12 Therefore ,log93=12.

c.

log2116

Set the expression equal to x.

log2116=x

Change to exponential form.

2x=116

Rewrite 16 as 24.

2x=124

2x=2−4

With the same base the exponents must be equal.

x=−4 Therefore ,log2116=−4.

Find the exact value of each logarithm without using a calculator:

- log12144

- log42

- log2132

- Answer

-

- 2

- 12

- −5

Find the exact value of each logarithm without using a calculator:

- log981

- log82

- log319

- Answer

-

- 2

- 13

- −2

Graph Logarithmic Functions

To graph a logarithmic function y=logax, it is easiest to convert the equation to its exponential form, x=ay. Generally, when we look for ordered pairs for the graph of a function, we usually choose an x-value and then determine its corresponding y-value. In this case you may find it easier to choose y-values and then determine its corresponding x-value.

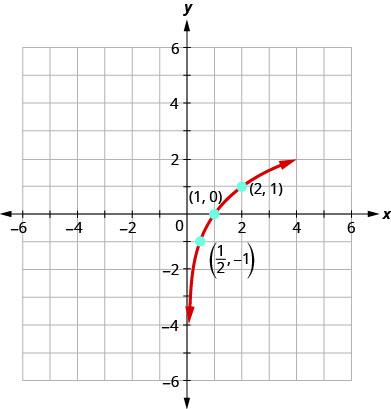

Graph y=log2x.

Solution:

To graph the function, we will first rewrite the logarithmic equation, y=log2x, in exponential form, 2y=x.

We will use point plotting to graph the function. It will be easier to start with values of y and then get x.

| y | 2y=x | (x,y) |

|---|---|---|

| −2 | 2−2=122=14 | (14,2) |

| −1 | 2−1=121=12 | (12,−1) |

| 0 | 20=1 | (1,0) |

| 1 | 21=2 | (2,1) |

| 2 | 22=4 | (4,2) |

| 3 | 23=8 | (8,3) |

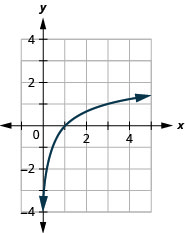

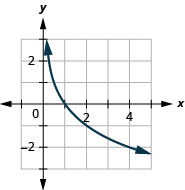

Graph: y=log3x.

- Answer

-

Figure 10.3.5

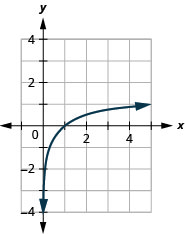

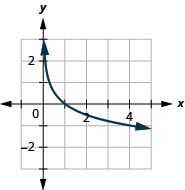

Graph: y=log5x.

- Answer

-

Figure 10.3.6

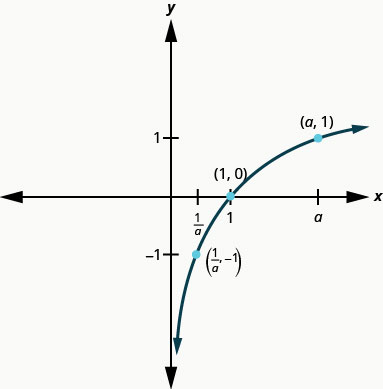

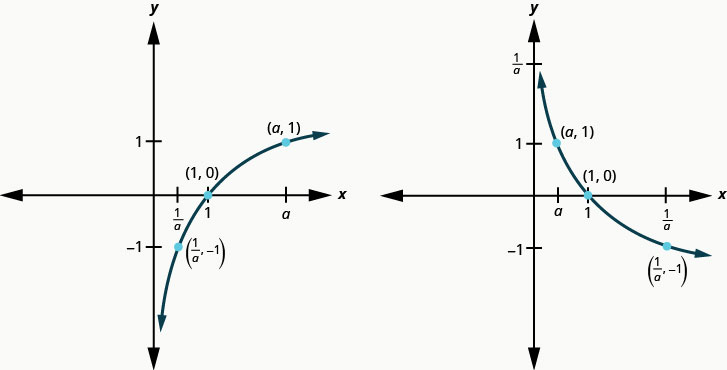

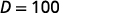

The graphs of y=log2x,y=log3x, and y=log5x are the shape we expect from a logarithmic function where a>1.

We notice that for each function the graph contains the point (1,0). This make sense because 0=loga1 means a0=1 which is true for any a.

The graph of each function, also contains the point (a,1). This makes sense as 1=logaa means a1=a. which is true for any a.

Notice too, the graph of each function y=logax also contains the point (1a,−1). This makes sense as −1=loga1a means a−1=1a, which is true for any a.

Look at each graph again. Now we will see that many characteristics of the logarithm function are simply ’mirror images’ of the characteristics of the corresponding exponential function.

What is the domain of the function? The graph never hits the y-axis. The domain is all positive numbers. We write the domain in interval notation as (0,∞).

What is the range for each function? From the graphs we can see that the range is the set of all real numbers. There is no restriction on the range. We write the range in interval notation as (−∞,∞).

When the graph approaches the y-axis so very closely but will never cross it, we call the line x=0, the y-axis, a vertical asymptote.

| Domain | (0,∞) |

| Range | (−∞,∞) |

| x-intercept | (1,0) |

| y-intercept | None |

| Contains | (a,1),(1a,−1) |

| Asymptote | y-axis |

Our next example looks at the graph of y=logax when 0<a<1.

Graph y=log13x.

Solution:

To graph the function, we will first rewrite the logarithmic equation, y=log13x, in exponential form, (13)y=x.

We will use point plotting to graph the function. It will be easier to start with values of y and then get x.

| y | (13)y=x | (x,y) |

|---|---|---|

| −2 | (13)−2=32=9 | (9,−2) |

| −1 | (13)−1=31=3 | (3,−1) |

| 0 | (13)0=1 | (1,0) |

| 1 | (13)1=13 | (13,1) |

| 2 | (13)2=19 | (19,2) |

| 3 | (13)3=127 | (127,3) |

Graph: y=log12x.

- Answer

-

Graph: y=log14x.

- Answer

-

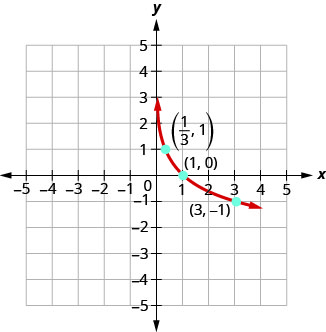

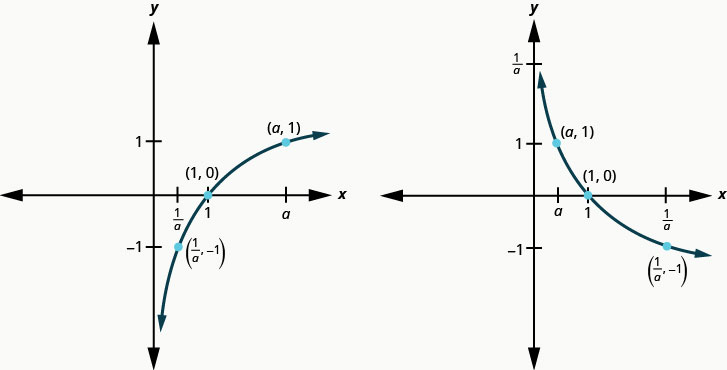

Now, let’s look at the graphs y=log12x,y=log13x and y=log14x, so we can identify some of the properties of logarithmic functions where 0<a<1.

The graphs of all have the same basic shape. While this is the shape we expect from a logarithmic function where 0<a<1.

We notice, that for each function again, the graph contains the points,(1,0),(a,1),(1a,−1). This make sense for the same reasons we argued above.

We notice the domain and range are also the same—the domain is (0,∞) and the range is (−∞,∞). The y-axis is again the vertical asymptote.

We will summarize these properties in the chart below. Which also include when a>1.

| When a>1 | When 0<a<1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1\)">Domain | (0,∞) | Domain | (0,∞) |

| 1\)">Range | (−∞,∞) | Range | (−∞,∞) |

| 1\)">x-intercept | (1,0) | x-intercept | (1,0) |

| 1\)">y-intercept | None | y-intercept | None |

| 1\)">Contains | (a,1),(1a,−1) | Contains | (a,1),(1a,−1) |

| 1\)">Asymptote | y -axis | Asymptote | y -axis |

| 1\)">Basic shape | Increasing | Basic shape | Decreasing |

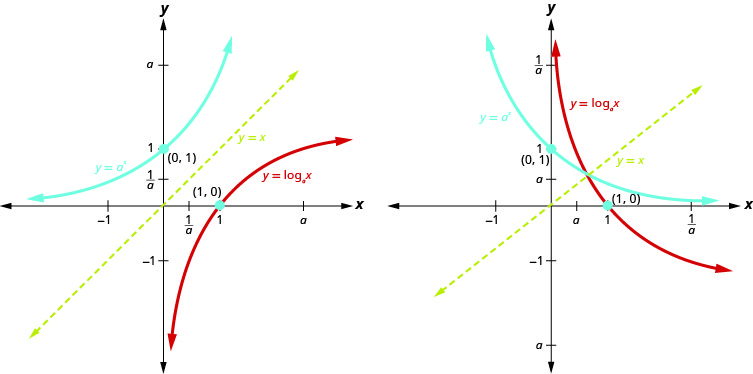

We talked earlier about how the logarithmic function f−1(x)=logax is the inverse of the exponential function f(x)=ax. The graphs in Figure 10.3.12 show both the exponential (blue) and logarithmic (red) functions on the same graph for both a>1 and 0<a<1.

Notice how the graphs are reflections of each other through the line y=x. We know this is true of inverse functions. Keeping a visual in your mind of these graphs will help you remember the domain and range of each function. Notice the x-axis is the horizontal asymptote for the exponential functions and the y-axis is the vertical asymptote for the logarithmic functions.

Solve Logarithmic Equations

When we talked about exponential functions, we introduced the number e. Just as e was a base for an exponential function, it can be used a base for logarithmic functions too. The logarithmic function with base e is called the natural logarithmic function. The function f(x)=logex is generally written f(x)=lnx and we read it as “el en of x.”

The function f(x)=lnx is the natural logarithmic function with base e, where x>0.

y=lnx is equivalent to x=ey

When the base of the logarithm function is 10, we call it the common logarithmic function and the base is not shown. If the base a of a logarithm is not shown, we assume it is 10.

The function f(x)=logx is the common logarithmic function with base 10, where x>0.

y=logx is equivalent to x=10y

To solve logarithmic equations, one strategy is to change the equation to exponential form and then solve the exponential equation as we did before. As we solve logarithmic equations, y=logax, we need to remember that for the base a, a>0 and a≠1. Also, the domain is x>0. Just as with radical equations, we must check our solutions to eliminate any extraneous solutions.

Solve:

- loga49=2

- lnx=3

Solution:

a.

loga49=2

Rewrite in exponential form.

a2=49

Solve the equation using the square root property.

a=±7

The base cannot be negative, so we eliminate a=−7.

a=7,a=−7

Check. a=7

loga49=2log749?=272?=4949=49

b.

lnx=3

Rewrite in exponential form.

e3=x

Check. x=e3

lnx=3lne3?=3e3=e3

Solve:

- loga121=2

- lnx=7

- Answer

-

- a=11

- x=e7

Solve:

- loga64=3

- lnx=9

- Answer

-

- a=4

- x=e9

Solve:

- log2(3x−5)=4

- lne2x=4

Solution:

a.

log2(3x−5)=4

Rewrite in exponential form.

24=3x−5

Simplify.

16=3x−5

Solve the equation.

21=3x

7=x

Check. x=7

log2(3x−5)=4log2(3⋅7−5)?=4log2(16)?=424?=1616=16

b.

lne2x=4

Rewrite in exponential form.

e4=e2x

Since the bases are the same the exponents are equal.

4=2x

Solve the equation.

2=x

Check. x=2

lne2x=4lne2⋅2?=4lne4=4e4=e4

Solve:

- log2(5x−1)=6

- lne3x=6

- Answer

-

- x=13

- x=2

Solve:

- log3(4x+3)=3

- lne4x=4

- Answer

-

- x=6

- x=1

Use Logarithmic Models in Applications

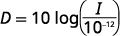

There are many applications that are modeled by logarithmic equations. We will first look at the logarithmic equation that gives the decibel (dB) level of sound. Decibels range from 0, which is barely audible to 160, which can rupture an eardrum. The 10−12 in the formula represents the intensity of sound that is barely audible.

Decibel Level of Sound

The loudness level, D, measured in decibels, of a sound of intensity, I, measured in watts per square inch is

D=10log(I10−12)

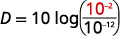

Extended exposure to noise that measures 85 dB can cause permanent damage to the inner ear which will result in hearing loss. What is the decibel level of music coming through ear phones with intensity 10−2 watts per square inch?

Solution:

|

|

| Substitute in the intensity level, I. |  |

| Simplify. |  |

| Since log1010=10. |  |

| Multiply. |  |

| The decibel level of music coming through earphones is 100 dB. |

What is the decibel level of one of the new quiet dishwashers with intensity 10−7 watts per square inch?

- Answer

-

The quiet dishwashers have a decibel level of 50 dB.

What is the decibel level heavy city traffic with intensity 10−3 watts per square inch?

- Answer

-

The decibel level of heavy traffic is 90 dB.

The magnitude R of an earthquake is measured by a logarithmic scale called the Richter scale. The model is R=logI, where I is the intensity of the shock wave. This model provides a way to measure earthquake intensity.

The magnitude R of an earthquake is measured byR=logI, where I is the intensity of its shock wave.

In 1906, San Francisco experienced an intense earthquake with a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale. Over 80% of the city was destroyed by the resulting fires. In 2014, Los Angeles experienced a moderate earthquake that measured 5.1 on the Richter scale and caused $108 million dollars of damage. Compare the intensities of the two earthquakes.

Solution:

To compare the intensities, we first need to convert the magnitudes to intensities using the log formula. Then we will set up a ratio to compare the intensities.

Convert the magnitudes to intensities.

R=logI

1906 earthquake

7.8=logI

Convert to exponential form.

I=107.8

2014 earthquake

5.1=logI

Convert to exponential form.

I=105.1

Form a ratio of the intensities.

Intensity for 1906 Intensity for 2014

Substitute in the values.

107.8105.1

Divide by subtracting the exponents.

102.7

Evaluate.

501

The intensity of the 1906 earthquake was about 501 times the intensity of the 2014 earthquake.

In 1906, San Francisco experienced an intense earthquake with a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale. In 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake also affected the San Francisco area, and measured 6.9 on the Richter scale. Compare the intensities of the two earthquakes.

- Answer

-

The intensity of the 1906 earthquake was about 8 times the intensity of the 1989 earthquake.

In 2014, Chile experienced an intense earthquake with a magnitude of 8.2 on the Richter scale. In 2014, Los Angeles also experienced an earthquake which measured 5.1 on the Richter scale. Compare the intensities of the two earthquakes.

- Answer

-

The intensity of the earthquake in Chile was about 1,259 times the intensity of the earthquake in Los Angeles.

Access these online resources for additional instruction and practice with evaluating and graphing logarithmic functions.

Key Concepts

- Properties of the Graph of y=logax:

| When a>1 | When 0<a<1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1\)">Domain | (0,∞) | Domain | (0,∞) |

| 1\)">Range | (−∞,∞) | Range | (−∞,∞) |

| 1\)">x-intercept | (1,0) | x-intercept | (1,0) |

| 1\)">y-intercept | None | y-intercept | None |

| 1\)">Contains | (a,1),(1a,−1) | Contains | (a,1),(1a,−1) |

| 1\)">Asymptote | y -axis | Asymptote | y -axis |

| 1\)">Basic shape | Increasing | Basic shape | Decreasing |

- Decibel Level of Sound: The loudness level, D, measured in decibels, of a sound of intensity, I, measured in watts per square inch is D=10log(I10−12).

- Earthquake Intensity: The magnitude R of an earthquake is measured by R=logI, where I is the intensity of its shock wave.

Glossary

- common logarithmic function

- The function f(x)=logx is the common logarithmic function with base 10, where x>0.

y=logx is equivalent to x=10y

- logarithmic function

- The function f(x)=logax is the logarithmic function with base a, where a>0,x>0, and a≠1.

y=logax is equivalent to x=ay

- natural logarithmic function

- The function f(x)=lnx is the natural logarithmic function with base e, where x>0.

y=lnx is equivalent to x=ey