5.2: Derivatives of Extended-Real Functions

- Page ID

- 19050

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)For a while (in §§2 and 3), we limit ourselves to extended-real functions. Below, \(f\) and \(g\) are real or extended real (f, \(g : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{*}).\) We assume, however, that they are not constantly infinite on any interval \((a, b), a<b\).

If \(f^{\prime}(p)>0\) at some \(p \in E^{1},\) then

\[x<p<y\]

implies

\[f(x)<f(p)<f(y)\]

for all \(x, y\) in a sufficiently small globe \(G_{p}(\delta)=(p-\delta, p+\delta).\)

Similarly, if \(f^{\prime}(p)<0,\) then \(x<p<y\) implies \(f(x)>f(p)>f(y)\) for \(x, y\) in some \(G_{p}(\delta).\)

- Proof

-

If \(f^{\prime}(p)>0,\) the "0" case in Definition 1 of §1, is excluded, so

\[f^{\prime}(p)=\lim _{x \rightarrow p} \frac{\Delta f}{\Delta x}>0.\]

Hence we must also have \(\Delta f / \Delta x>0\) for \(x\) in some \(G_{p}(\delta)\).

It follows that \(\Delta f\) and \(\Delta x\) have the same sign in \(G_{p}(\delta);\) i.e.,

\[f(x)-f(p)>0 \text { if } x>p \text { and } f(x)-f(p)<0 \text { if } x<p.\]

(This implies \(f(p) \neq \pm \infty.\) Why? Hence

\[x<p<y \Longrightarrow f(x)<f(p)<f(y),\]

as claimed; similarly in case \(f^{\prime}(p)<0. \quad \square\)

If \(f(p)\) is the maximum or minimum value of \(f(x)\) for \(x\) in some \(G_{p}(\delta),\) then \(f^{\prime}(p)=0;\) i.e., \(f\) has a zero derivative, or none at all, at \(p.\)

For, by Lemma 1, \(f^{\prime}(p) \neq 0\) excludes a maximum or minimum at \(p.\) (Why?)

Note 1. Thus \(f^{\prime}(p)=0\) is a necessary condition for a local maximum or minimum at \(p.\) It is insufficient, however. For example, if \(f(x)=x^{3}, f\) has no maxima or minima at all, yet \(f^{\prime}(0)=0 .\) For sufficient conditions, see §6.

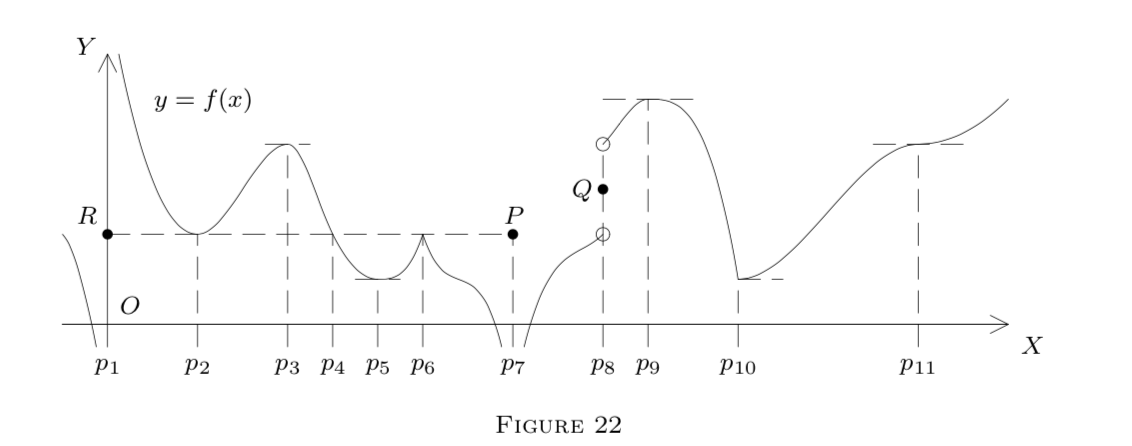

Figure 22 illustrates these facts at the points \(p_{2}, p_{3}, \ldots, p_{11}.\) Note that in Figure 22, the isolated points \(P, Q, R\) belong to the graph.

Geometrically, \(f^{\prime}(p)=0\) means that the tangent at \(p\) is horizontal, or that a two-sided tangent does not exist at \(p.\)

Let \(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{*}\) be relatively continuous on an interval \([a, b]\), with \(f^{\prime} \neq 0\) on \((a, b).\) Then \(f\) is strictly monotone on \([a, b],\) and \(f^{\prime}\) is signconstant there (possibly 0 at a and b), with \(f^{\prime} \geq 0\) if \(f \uparrow,\) and \(f^{\prime} \leq 0\) if \(f \downarrow\).

- Proof

-

By Theorem 2 of Chapter 4, §8, \(f\) attains a least value \(m,\) and a largest value \(M,\) at some points of \([a, b].\) However, neither can occur at an interior point \(p \in(a, b),\) for, by Corollary 1, this would imply \(f^{\prime}(p)=0,\) contrary to our assumption.

Thus \(M=f(a)\) or \(M=f(b);\) for the moment we assume \(M=f(b)\) and \(m=f(a).\) We must have \(m<M,\) for \(m=M\) would make \(f\) constant on \([a, b]\), implying \(f^{\prime}=0.\) Thus \(m=f(a)<f(b)=M.\)

Now let \(a \leq x<y \leq b\). Applying the previous argument to each of the intervals \([a, x],[a, y],[x, y],\) and \([x, b]\) (now using that \(m=f(a)<f(b)=M )\), we find that

\[f(a) \leq f(x)<f(y) \leq f(b). \quad \text { (Why?) }\]

Thus \(a \leq x<y \leq b\) implies \(f(x)<f(y);\) i.e., \(f\) increases on \([a, b].\) Hence \(f^{\prime}\) cannot be negative at any \(p \in[a, b],\) for, otherwise, by Lemma 1, \(f\) would decrease at \(p.\) Thus \(f^{\prime} \geq 0\) on \([a, b].\)

In the case \(M=f(a)>f(b)=m,\) we would obtain \(f^{\prime} \leq 0\). \(\quad \square\)

Caution: The function \(f\) may increase or decrease at \(p\) even if \(f^{\prime}(p)=0.\)

See Note 1.

If : \(E^{1} \rightarrow E^{*}\) is relatively continuous on \([a, b]\) and if \(f(a)=f(b),\) then \(f^{\prime}(p)=0\) for at least one interior point \(p \in(a, b)\).

For, if \(f^{\prime} \neq 0\) on all of \((a, b),\) then by Theorem 1, \(f\) would be strictly monotone on \([a, b],\) so the equality \(f(a)=f(b)\) would be impossible.

Figure 22 illustrates this on the intervals \(\left[p_{2}, p_{4}\right]\) and \(\left[p_{4}, p_{6}\right],\) with \(f^{\prime}\left(p_{3}\right)=\) \(f^{\prime}\left(p_{5}\right)=0.\) A discontinuity at 0 causes an apparent failure on \([0, p_{2}].\)

Note 2. Theorem 1 and Corollary 2 hold even if \(f(a)\) and \(f(b)\) are infinite, if continuity is interpreted in the sense of the metric \(\rho^{\prime}\) of Problem 5 in Chapter 3, §11. (Weierstrass' Theorem 2 of Chapter 4, §8 applies to \(\left(E^{*}, \rho^{\prime}\right),\) with the same proof.)

Let the functions \(f, g : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{*}\) be relatively continuous and finite on \([a, b]\) and have derivatives on \((a, b),\) with \(f^{\prime}\) and \(g^{\prime}\) never both infinite at the same point \(p \in(a, b).\) Then

\[g^{\prime}(q)[f(b)-f(a)]=f^{\prime}(q)[g(b)-g(a)] \text { for at least one } q \in(a, b).\]

- Proof

-

Let \(A=f(b)-f(a)\) and \(B=g(b)-g(a).\) We must show that \(A g^{\prime}(q)=B f^{\prime}(q)\) for some \(q \in(a, b)\). For this purpose, consider the function \(h=A g-B f\). It is relatively continuous and finite on \([a, b],\) as are \(g\) and \(f.\) Also,

\[h(a)=f(b) g(a)-g(b) f(a)=h(b) . \quad \text { (Verify!) }\]

Thus by Corollary 2, \(h^{\prime}(q)=0\) for some \(q \in(a, b).\) Here, by Theorem 4 of §1, \(h^{\prime}=(A g-B f)^{\prime}=A g^{\prime}-B f^{\prime}.\) (This is legitimate, for, by assumption, \(f^{\prime}\) and \(g^{\prime}\) never both become infinite, so no indeterminate limits occur.) Thus \(h^{\prime}(q)=A g^{\prime}(q)-B f^{\prime}(q)=0,\) and (1) follows. \(\quad \square\)

If \(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{1}\) is relatively continuous on \([a, b]\) with a derivative on \((a, b),\) then

\[f(b)-f(a)=f^{\prime}(q)(b-a) \text { for at least one } q \in(a, b).\]

- Proof

-

Take \(g(x)=x\) in Theorem 2, so \(g^{\prime}=1\) on \(E^{1}. \square\)

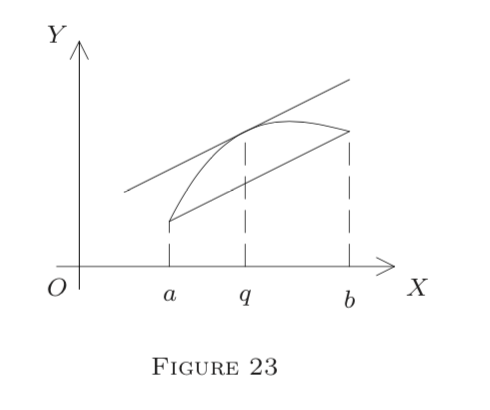

Note 3. Geometrically,

\[\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}\]

is the slope of the secant through \((a, f(a))\) and \((b, f(b)),\) and \(f^{\prime}(q)\) is the slope of the tangent line at \(q.\) Thus Corollary 3 states that the secant is parallel to the tangent at some intermediate point \(q;\) see Figure 23. Theorem 2 states the same for curves given parametrically: \(x=f(t), y=g(t)\).

Let \(f\) be as in Corollary 3. Then

(i) \(f\) is constant on \([a, b]\) iff \(f^{\prime}=0\) on \((a, b)\);

(ii) \(f \uparrow\) on \([a, b]\) iff \(f^{\prime} \geq 0\) on \((a, b);\) and

(iii) \(f \downarrow\) on \([a, b]\) iff \(f^{\prime} \leq 0\) on \((a, b)\).

- Proof

-

Let \(f^{\prime}=0\) on \((a, b).\) If \(a \leq x \leq y \leq b,\) apply Corollary 3 to the interval \([x, y]\) to obtain

\[f(y)-f(x)=f^{\prime}(q)(y-x) \text { for some } q \in(a, b) \text { and } f^{\prime}(q)=0.\]

Thus \(f(y)-f(x)=0\) for \(x, y \in[a, b],\) so \(f\) is constant.

The rest is left to the reader. \(\quad \square\)

Let \(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{1}\) be relatively continuous and strictly monotone on an interval \(I \subseteq E^{1}\). Let \(f^{\prime}(p) \neq 0\) at some interior point \(p \in I.\) Then the inverse function \(g=f^{-1}\) (with \(f\) restricted to \(I)\) has a derivative at \(q=f(p),\) and

\[g^{\prime}(q)=\frac{1}{f^{\prime}(p)}.\]

(If \(f^{\prime}(p)=\pm \infty,\) then \(g^{\prime}(q)=0.)\)

- Proof

-

By Theorem 3 of Chapter 4, §9, \(g=f^{-1}\) is strictly monotone and relatively continuous on \(f[I],\) itself an interval. If \(p\) is interior to \(I,\) then \(q=f(p)\) is interior to \(f[I].\) (Why?)

Now if \(y \in f[I],\) we set

\[\Delta g=g(y)-g(q), \Delta y=y-q, x=f^{-1}(y)=g(y), \text { and } f(x)=y\]

and obtain

\[\frac{\Delta g}{\Delta y}=\frac{g(y)-g(q)}{y-q}=\frac{x-p}{f(x)-f(p)}=\frac{\Delta x}{\Delta f} \text { for } x \neq p.\]

Now if \(y \rightarrow q,\) the continuity of \(g\) at \(q\) yields \(g(y) \rightarrow g(q);\) i.e., \(x \rightarrow p.\) Also, \(x \neq p\) iff \(y \neq q\), for \(f\) and \(g\) are one-to-one functions. Thus we may substitute \(y=f(x)\) or \(x=g(y)\) to get

\[g^{\prime}(q)=\lim _{y \rightarrow q} \frac{\Delta g}{\Delta y}=\lim _{x \rightarrow p} \frac{\Delta x}{\Delta f}=\frac{1}{\lim _{x \rightarrow p}(\Delta f / \Delta x)}=\frac{1}{f^{\prime}(p)},\]

where we use the convention \(\frac{1}{\infty}=0\) if \(f^{\prime}(p)=\infty. \quad \square\)

(A) Let

\[f(x)=\log _{a}|x| \text { with } f(0)=0.\]

Let \(p>0.\) Then \((\forall x>0)\)

\[\begin{aligned} \Delta f &=f(x)-f(p)=\log _{a} x-\log _{a} p=\log _{a}(x / p) \\ &=\log _{a} \frac{p+(x-p)}{p}=\log _{a}\left(1+\frac{\Delta x}{p}\right). \end{aligned}\]

Thus

\[\frac{\Delta f}{\Delta x}=\log _{a}\left(1+\frac{\Delta x}{p}\right)^{1 / \Delta x}.\]

Now let \(z=\Delta x / p.\) (Why is this substitution admissible?) Then using the formula

\[\lim _{z \rightarrow 0}(1+z)^{1 / z}=e \quad \text { (see Chapter 4, §2, Example (C)) }\]

and the continuity of the log and power functions, we obtain

\[f^{\prime}(p)=\lim _{x \rightarrow p} \frac{\Delta f}{\Delta x}=\lim _{z \rightarrow 0} \log _{a}\left[(1+z)^{1 / z}\right]^{1 / p}=\log _{a} e^{1 / p}=\frac{1}{p} \log _{a} e.\]

The same formula results also if \(p<0,\) i.e., \(|p|=-p.\) At \(p=0, f\) has one-sided derivatives \(( \pm \infty)\) only (verify!), so \(f^{\prime}(0)=0\) by Definition 1 in §1.

(B) The inverse of the log \(_{a}\) function is the exponential \(g : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{1},\) with

\[g(y)=a^{y} \quad(a>0, a \neq 1).\]

By Theorem 3, we have

\[\left(\forall q \in E^{1}\right) \quad g^{\prime}(q)=\frac{1}{f^{\prime}(p)}, p=g(q)=a^{q}.\]

Thus

\[g^{\prime}(q)=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{p} \log _{a} e}=\frac{p}{\log _{a} e}=\frac{a^{q}}{\log _{a} e}.\]

Symbolically,

\[\left(\log _{a}|x|\right)^{\prime}=\frac{1}{x} \log _{a} e(x \neq 0) ; \quad\left(a^{x}\right)^{\prime}=\frac{a^{x}}{\log _{a} e}=a^{x} \ln a.\]

In particular, if \(a=e,\) we have \(\log _{e} a=1\) and \(\log _{a} x=\ln x ;\) hence

\[(\ln |x|)^{\prime}=\frac{1}{x}(x \neq 0) \quad \text { and } \quad\left(e^{x}\right)^{\prime}=e^{x} \quad\left(x \in E^{1}\right).\]

(C) The power function \(g :(0,+\infty) \rightarrow E^{1}\) is given by

\[g(x)=x^{a}=\exp (a \cdot \ln x) \text { for } x>0 \text { and fixed } a \in E^{1}.\]

By the chain rule (§1, Theorem 3), we obtain

\[g^{\prime}(x)=\exp (a \cdot \ln x) \cdot \frac{a}{x}=x^{a} \cdot \frac{a}{x}=a \cdot x^{a-1}.\]

Thus we have the symbolic formula

\[\left(x^{a}\right)^{\prime}=a \cdot x^{a-1} \text { for } x>0 \text { and fixed } a \in E^{1}.\]

If \(f : E^{1} \rightarrow E^{*}\) is relatively continuous and has a derivative on an interval I, then \(f^{\prime}\) has the Darboux property (Chapter 4, §9 ) on \(I.\)

- Proof

-

Let \(p, q \in I\) and \(f^{\prime}(p)<c<f^{\prime}(q).\) Put \(g(x)=f(x)-c x.\) Assume \(g^{\prime} \neq 0\) on \((p, q)\) and find a contradiction to Theorem 1. Details are left to the reader. \(\quad \square\)