6.4: Merchandising (How Does It All Come Together?)

- Page ID

- 22100

Running a business requires you to integrate all of the concepts in this chapter. From discounts to markups and markdowns, all the numbers must fit together for you to earn profits in the long run. It is critical to understand how pricing decisions affect the various financial aspects of your business and to stay on top of your numbers.

Merchandising does not involve difficult concepts, but to do a good job of it you need to keep track of many variables and observe how they relate to one another. Merchandising situations in this section will apply all of the previously discussed pricing concepts. Next, the concept of maintained markup helps you understand the combined effect of markup and markdown decisions on list profitability. Finally, you will see that coupons and rebates influence expenses and profitability in several ways beyond the face value of the discounts offered.

The Complete Pricing Picture

Up to this point, you have examined the various components of merchandising as separate topics. Your study of basic product pricing has included the following:

- Taking an MSRP or list price and applying discounts to arrive at a product’s cost

- Marking up a product by adding expenses and profits to the cost to arrive at a regular selling price

- Marking down a product by applying a discount and arriving at a sale price

- Working with various percentages in both markup and markdown situations to either simplify calculations or present a clearer pricing picture

Now is the time to tie all of these merchandising concepts together. Section 6.2 introduced the concept of a markup chart to understand the relationship between various markup components. The figure below extends this figure to include all of the core elements of merchandising.

The figure reveals the following characteristics:

- You calculate the cost of a product by applying a discount formula. The net price, \(N\), is synonymous with cost, \(C\).

- When you mark a product down, not only is the profit reduced but the markup dollars are also reduced. The following relationships exist when a product is on sale:

\[M\$_{onsale}=E+P_{onsale} \quad \text { OR } \quad M\$_{onsale}=M\$-D\$\nonumber \]

\[P_{onsale}=P-D\$\nonumber \]

- At break-even (remember, \(P\) or \(P_{onsale}\) is zero) a sale product has the following relationships:\[\begin{aligned}M\$_{onsale}=E \\S_{onsale}=C+E \\D\$=P \end{aligned} \nonumber \]

None of these relationships represent new formulas. Instead, these reflect a deeper understanding of the relationships between the markup and markdown formulas.

How It Works

Follow these steps to solve complete merchandising scenarios:

Step 1: It is critically important to correctly identify both the known and unknown merchandising variables that you are asked to calculate.

Step 2: For each of the unknown variables in step 1, examine Formula 6.1 through Formula 6.12. Locate which formulas contain the unknown variable. You must solve one of these formulas to arrive at the answer. Based on the information provided, examine these formulas to determine which formula may be solvable. Write out this formula, identifying which components you know and which components remain unknown. For example, assume that in step 1 you were asked to solve for the expenses, or \(E\). In looking at the formulas, you find this variable appears only in Formula 6.5 and Formula 6.6, meaning that you must use one of these two formulas to calculate the expenses. Suppose that, in reviewing the known variables from step 1, you already have the markup amount and the profit. In this case, Formula 6.6 would be the right formula to calculate expenses with.

Step 3: Note the unknown variables among all the formulas written in step 2. Are there common unknown variables among these formulas? These common variables are critical variables. Solving for these common unknowns is the key to completing the question. Note that these unknown variables may not directly point to the information you were requested to calculate, and they do not resolve the merchandising scenario in and of themselves. However, without these variables you cannot solve the scenario. For example, perhaps in step 1 you were requested to calculate both the markup on cost percent (\(MoC\%\)) and the markup on selling price percent (\(MoS\%\)). In step 2, noting that these variables are found only in Formula 6.8 and Formula 6.9, you wrote them down. Examination of these formulas revealed that you know the cost and selling price variables. However, in both formulas the markup dollars remain unknown. Therefore, markup dollars is the critical unknown variable. You must solve for markup dollars using Formula 6.7, which will then allow you to calculate the markup percentages.

Step 4: Apply any of the merchandising formulas from Formula 6.1 to Formula 6.12 to calculate the unknown variables required to solve the formulas. Your goal is to identify all required variables and then solve the original unknown variables from step 1.

Things To Watch Out For

Before proceeding, take a few moments to review the various concepts and formulas covered earlier in this chapter. A critical and difficult skill is now at hand. As evident in steps 2 through 4 of the solving process, you must use your problem-solving skills to figure out which formulas to use and in what order. Here are three suggestions to help you on your way:

- Analyze the question systematically. Conscientiously use the Plan, Understand, Perform, and Present model.

- If you are unsure of how the pieces of the puzzle fit together, try substituting your known variables into the various formulas. You are looking for

- Any solvable formulas with only one unknown variable or

- Any pair of formulas with the same two unknowns, since you can solve this system using your algebraic skills of solving two linear equations with two unknowns (covered in Section 2.5).

- Merchandising has multiple steps. Think through the process. When you solve one equation for an unknown variable, determine how knowing that variable affects your ability to solve another formula. As mentioned in step 3, there is usually a critical unknown variable. Once you determine the value of this variable, a domino effect allows you to solve any other remaining formulas.

A skateboard shop stocks a Tony Hawk Birdhouse Premium Complete Skateboard. The MSRP for this board is $82. If the shop is going to stock the board, it must order at least 25 units. The known information is as follows:

- The supplier offers a retail trade discount of 37% with a quantity discount of 12% for orders that exceed 15 units.

- Typical expenses associated with selling this premium skateboard amount to 31% of the regular selling price.

- The skateboard shop wants each of its products to have profitability of 13% of the regular selling price.

- In the event that the skateboards do not sell by the end of the season, the skateboard shop always holds an end-of-season clearance sale where it marks down its products to the break-even selling price.

Using this information about the skateboard, determine the following:

- Cost

- Regular unit selling price

- Markup on cost percentage

- Markup on selling price percentage

- Sale price

- Markdown percentage

Solution

In order, you are looking for \(C\), \(S\), \(MoC\%\), \(MoS\%\), \(S_{onsale}\), and \(d\)(markdown).

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The list price, two discounts (note the store qualifies for both since it meets the minimum quantity criteria), expense and profit information, as well as information on the sale price are known:

\[\begin{aligned}

&L=\$ 82.00\\

&d_{1}=0.37\\

&d_{2}=0.12\\

&E=0.31 S\\

&P=0.13 S

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

\[S_{onsale} = \text {break-even price} \nonumber \]

The unknown variables are: \(C\), \(S\), \(MoC\%\), \(MoS\%\), \(S_{onsale}\), and \(d\)(markdown).

How You Will Get There

Step 2:

- Cost and net price are synonymous. Net price appears in Formula 6.1, Formula 6.2b, and Formula 6.3. Since you know list price and two discounts, calculate cost through Formula 6.3.

- Selling price appears in Formula 6.5, Formula 6.7, Formula 6.9, Formula 6.10, Formula 6.11a, and Formula 6.11b. Known variables include expenses and profit. You will know the cost once you have solved part (a). Choose Formula 6.5.

- Markup on cost percent appears only in Formula 6.8. You will know the cost once you have solved part (a). \(M\$\) is an unknown variable.

- Markup on selling price percent appears only in Formula 6.9. You will know the selling price once you have solved parts (a) and (b). \(M\$\) is an unknown variable.

- A break-even price uses an adapted Formula 6.5. You will know the cost once you have solved part (a) and determined the expenses based on the selling price in part (b).

- Markdown percent appears in Formula 6.10, Formula 6.11a, and Formula 6.12. You will know the regular price once you have solved part (b). You will know the sale price once you have solved part (e). Choose Formula 6.12.

Step 3:

From the above rationalization, the only unknown variables are cost and markup dollars. Once you know these two variables you can complete all other formulas. Calculate cost as described in step 2a. To calculate markup dollars, use Formula 6.6, Formula 6.7, Formula 6.8, and Formula 6.9. Once you know the cost and selling price from parts 2(a) and 2(b), you can apply Formula 6.7, rearranging for markup dollars.

Perform

Step 4:

a. \(C = N = \$82 × (1 – 0.37) × (1 – 0.12) = \$45.46\)

b. \(\begin{aligned} S &=\$ 45.46+0.31 S+0.13S \\ 0.56 S &=\$ 45.46 \\ S&=\$ 81.18 \end{aligned}\)

c. As determined in step 3, you need markup dollars first.\[\begin{aligned} &\$ 81.18=\$ 45.46+M \$\\&\$ 35.72=M \$\end{aligned} \nonumber \]Now Solve:\[MoC \%=\dfrac{\$ 35.72}{\$ 45.46} \times 100=78.5746 \% \nonumber \]

d. \(MoS \%=\dfrac{\$ 35.72}{\$ 81.18} \times 100=44 \%\)

e. \(S_{onsale}=S_{BE}=\$ 45.46+0.31(\$ 81.18)=\$ 70.63\)

f. \[\begin{aligned}

\$ 70.63 &=\$ 81.18 \times(1-d) \\

0.87 &=1-d \\

0.13 &=d

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Calculator Instructions

For part (d) only, use 2nd Profit

| CST | SEL | MAR |

|---|---|---|

| 45.46 | 81.18 | Answer: 44 |

The cost of the skateboard is $45.46. The regular selling price for the skateboard is $81.18. This is a markup on cost percent of 78.5746% and a markup on selling price percent of 44%. To clear out the skateboards, the sale price is $70.63, representing a markdown of 13%.

Maintained Markup

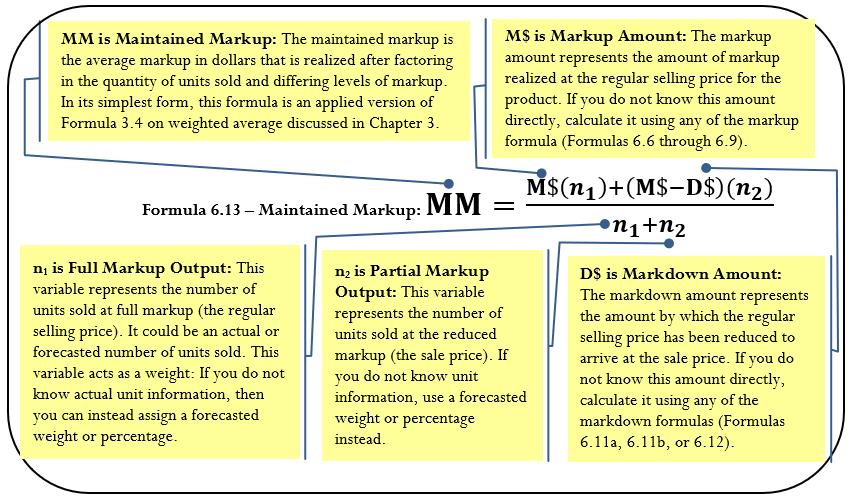

A price change results in a markup change. Whenever a selling price is reduced to a sale price, it has been demonstrated that the amount of the markup decreases (from \(M\$\) to \(M\$_{onsale}\)) by the amount of the discount (\(D\$\)). This means that some of the products are sold at full markup and some at a partial markup. For businesses, the strategic marking up of a product must factor in the reality that they do not sell every product at the same level of markup. Therefore, if a business must achieve a specified level of markup on its products, it must set its price such that the average of all markups realized equals its markup objective. The average markup that is realized in selling a product at different price points is known as the maintained markup.

The Formula

To understand the formula, assume a company has 100 units for sale. From past experience, it knows that 90% of the products sell for full price and 10% sell at a sale price because of discounts, damaged goods, and so on. At full price, the product has a markup of $10, and 90 units are sold at this level, equaling a total markup of $900. On sale, the product is discounted $5, resulting in a markup of $5 with 10 units sold, equaling a total markup of $50. The combined total markup is $950. Therefore, the maintained markup is \(\$ 950 \div 100=\$ 9.50\) per unit. If the company’s goal is to achieve a $10 maintained markup, this pricing structure will not accomplish that goal. Formula 6.13 summarizes the calculations involved with maintained markup.

Important Notes

Formula 6.13 assumes that only one price reduction applies, implying that there is only one regular price and one sale price. In the event that a product has more than one sale price, you can expand the formula to include more terms in the numerator. To expand the formula for each additional sale price required:

- Extend the numerator by adding another \((\mathrm{M}\$ − \mathrm{D}$)(n_x)\), where the \(\mathrm{D}\$\) always represents the total difference between the selling price and the corresponding sale price and \(n_x\) is the quantity of units sold at that level of markup.

- Extend the denominator by adding another \(n_x\) as needed.

For example, if you had the regular selling price and two different sale prices, Formula 6.13 appears as:

\[MM=\dfrac{M \$\left(n_{1}\right)+\left(M \$-D \$_{1}\right)\left(n_{2}\right)+\left(M \$-D \$_{2}\right)\left(n_{3}\right)}{n_{1}+n_{2}+n_{3}} \nonumber \]

How It Works

Follow these steps to calculate the maintained markup:

Step 1: Identify information about the merchandising scenario. You must either know markup dollars at each pricing level or identify all merchandising information such as costs, expenses, profits, and markdown information. Additionally, you must know the number of units sold at each price level. If unit information is not available, you will identify a weighting based on percentages.

Step 2: If step 1 already identifies the markup dollars and discount dollars, skip this step. Otherwise, you must use any combination of merchandising formulas (Formula 6.1 to Formula 6.12) to calculate markup dollars and discount dollars.

Step 3: Calculate maintained markup by applying Formula 6.13.

A company’s pricing objective is to maintain a markup of $5. It knows that some of the products sell at regular price and some of the products sell at a sale price. When setting the regular selling price, will the markup amount be more than, equal to, or less than $5?

- Answer

-

More than $5. In order to average to $5, the markup at regular price must be higher than $5 and the markup at sale price must be lower than $5.

A grocery store purchases a 10 kg bag of flour for $3.99 and resells it for $8.99. Occasionally the bag of flour is on sale for $6.99. For every 1,000 units sold, 850 are estimated to sell at the regular price and 150 at the sale price. What is the maintained markup on the flour?

Solution

You are looking to calculate the maintained markup (\(MM\)).

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The cost, selling price, and sale price information along with the units sold at each price are known:

\(C = \$3.99, S = \$8.99, S_{onsale} = $6.99, n_1 = 850, n_2 = 150\)

How You Will Get There

Step 2:

To calculate markup dollars, apply Formula 6.7, rearranging for \(M\$\). To calculate markdown dollars, apply Formula 6.11b.

Step 3: Calculate maintained markup by applying Formula 6.13.

Perform

Step 2:

Markup amount:

\[\begin{aligned}

\$ 8.99 &=\$ 3.99+C \\

C &=\$ 5.00

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Markdown amount:

\[D\$ = \$8.99 − \$6.99 = \$2.00 \nonumber \]

Step 3:

\[MM=\dfrac{\$ 5(850)+(\$ 5-\$ 2)(150)}{850+150}=\$ 4.70 \nonumber \]

On average, the grocery store will maintain a $4.70 markup on the flour.

Maplewood Golf Club has set a pricing objective to maintain a markup of $41.50 on all 18-hole golf and cart rentals. The cost of providing the golf and rental is $10. Every day, golfers before 3 p.m. pay full price while “twilight” golfers after 3 p.m. receive a discounted price equalling $30 off. Typically, 25% of the club’s golfers are “twilight” golfers. What regular price and sale price should the club set to meet its pricing objective?

Solution

The golf club needs to calculate the regular selling price (\(S\)) and the sale price (\(S_{onsale}\)).

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The cost information along with the maintained markup, markdown amount, and weighting of customers in each price category are known:

\(C = \$10, MM = \$41.50, D\$ = \$30, n_1 = 100\% − 25\% = 75\%, n_2 = 25\%\)

How You Will Get There

Reverse steps 2 and 3 since you must solve Formula 6.13 first and use this information to calculate the selling price and sale price.

Step 3:

Apply Formula 6.13, rearranging for \(M\$\).

Step 2:

Calculate the selling price by applying Formula 6.7.

Step 2 (continued):

Calculate the sale price by applying Formula 6.11b, rearranging for (\(S_{onsale}\)).

Perform

Step 3:

\[\begin{aligned}

\$ 41.50 &=\dfrac{M\$(0.75)+(M\$-\$ 30)(0.25)}{0.75+0.25} \\

\$ 41.50 &=0.75 M\$+0.25M\$-\$ 7.50 \\

\$ 49 &=M\$

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Step 2:

\[S = \$10 + \$49 = \$59 \nonumber \]

Step 2 (continued):

\[\begin{aligned}

\$ 30&=\$ 59-S_{onsale} \\

S_{onsale}&=\$ 29

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

In order to achieve its pricing objective, Maplewood Golf Club should set a regular price of $59 and a “twilight” sale price of $29.

The Pricing Impact of Coupons and Mail-in Rebates

Consumers sometimes need a nudge to help them decide on a purchase. Have you ever been thinking about buying a product but put it off for a variety of reasons? Then, while browsing online one day, you suddenly come across a coupon. You print it off and hurry down to your local store, because the coupon expires in the next few days. You just participated in a price adjustment.

A marketing price adjustment is any marketing activity executed by a member of the distribution channel for the purpose of altering a product’s price. This includes an alteration to the regular unit selling price or a sale price. For example, Sony could distribute a rebate giving its consumers $50 off the price of one of its televisions. Alternatively, Superstore could run a special promotion where customers receive $30 off if they purchase at least $250 in merchandise.

When making price adjustments, businesses must understand the full impact on the bottom line. Many inexperienced businesses distribute coupons for $1 off, assuming that the only cost to be accounted for is the $1. This is untrue for most price adjustments.

These marketing price adjustments reduce the prices that you pay as a consumer. Certainly, some price adjustments are more advantageous than others. Although they come in many types, this section focuses on two of the most widely used price adjustments: manufacturer coupons and mail-in rebates.

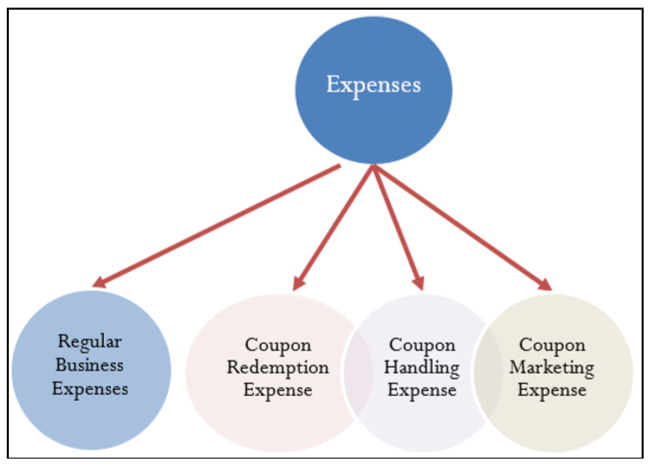

Manufacturer Coupons

A coupon is a promotion that entitles a consumer to receive a certain benefit, most commonly in the form of a price reduction. Coupons are typically offered by manufacturers to consumers.

The decision of a manufacturer to issue a coupon affects the expenses associated with the product in three ways.

- Coupon Redemption Expense. The coupon redemption expense is the dollar amount price reduction that the coupon offers, also known as the face value of the coupon. The manufacturer must pay out this amount to the reseller as a reimbursement for redeeming the coupon, increasing the expenses accordingly. For example, if a coupon is for $3 off, then the coupon redemption expense is $3.

- Coupon Handling Expense. Most commonly, retailers are the resellers that redeem manufacturer coupons. The resulting coupon handling expense for the manufacturer is known as a handling fee or handling charge, payable to the retailer. The manufacturer offers financial compensation to the retailer for redeeming the coupon, filling out the paperwork, and submitting it to manufacturer for reimbursement. Ultimately, the retailer should not be out any money for participating in the promotion. For example, in the small print a coupon may indicate that there is a $0.09 handling fee. This amount is payable to the retailer upon the manufacturer’s receipt of the redeemed coupon.

- Coupon Marketing Expense. Coupons do not just magically appear in consumer hands. Companies must pay for the creation, distribution, and redemption of the coupons, which is known as the coupon marketing expense:

- Coupons are designed, turned into print-ready artwork, and printed. This incurs design, labor, and material costs.

- Coupons are commonly distributed separately from the product in media such as magazines, flyers, and newspapers. This requires the purchase of ad space.

- Coupons are commonly redeemed through coupon clearinghouses that handle coupon redemption requests. Manufacturers must pay the fees charged by the clearinghouse.

The manufacturer issuing the coupon estimates how many coupons it expects consumers will redeem and assigns the average of the coupon marketing costs to each unit based on the forecasted volume.

It should be evident that the decision to issue coupons results in expenses much higher than the face value of the coupon. All three of the expenses listed above are added to the product’s regular expenses. The end result is that the unit expenses increase while unit profits decrease.

As a consumer, you can appreciate the immediacy of the price reduction a coupon offers you at the cash register. Unlike with mail-in rebates, there is nothing further you need to do.

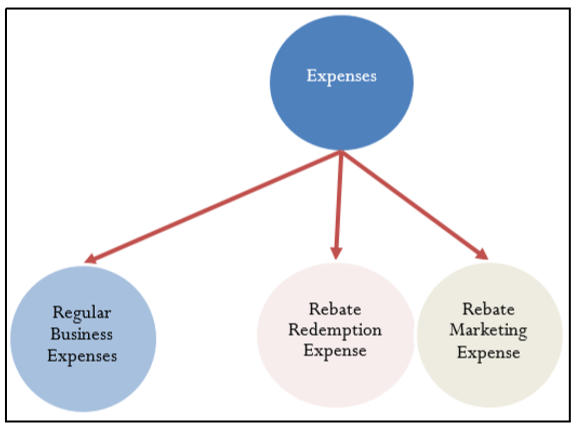

Mail-In Rebates

Have you ever purchased an item that came with a mail-in rebate but not submitted the rebate because it was too much hassle? Was your rebate refused because you failed to meet the stringent requirements? If you answered yes to either of these questions, then you have joined the ranks of many other consumers. In fact, marketers know you will either not mail in your rebates (some estimates are that 50% to 98% of mail-in rebates go unredeemed), or you will fail to send the required supporting materials. From a pricing point of view, this means that more product is sold at the regular price! That is why marketers use mail-in rebates.

Mail-in rebates are similar to coupons; however, there is a distinct difference in how the price adjustment works. A mail-in rebate is a refund at a later date after the purchase has already been made, whereas coupons instantly reward consumers with a price reduction at the cash register. Mail-in rebates commonly require consumers to fill in an information card as well as meet a set of stringent requirements (such as cutting out UPC codes and providing original receipts) that must be mailed in to the manufacturer at the consumer’s expense (see the photo for an example). After a handling time of perhaps 8 to 12 weeks and if the consumer has met all requirements, the manufacturer issues a cheque in the amount of the rebate and sends it to the consumer.

With coupons there are three associated expenses: coupon redemption, handling, and marketing. In the case of rebates, since the participants in the channel are not involved with the rebate redemption, no handling expenses are paid out to the retailers.

- Rebate Redemption Expense. The rebate redemption expense is the dollar amount price reduction that the rebate offers, also known as the face value of the rebate. This amount must be paid out to the consumer, commonly in the form of a cheque. For example, if a rebate is for $50, then this is the amount sent to the consumer. This increases expenses, but often not by the full $50. Recall that though many consumers purchase the product because the rebate is offered, not all of them redeem the rebate. To calculate the unit expense many companies average the rebate redemption amount based on the number of rebates they expect to fulfill. Take, for example, a company that issues a $50 rebate on the purchase of a surround sound system. From past experience, it knows that only 5% of the rebates are actually redeemed properly and thus paid out. Therefore, the increase in expenses is not $50, but 5% of $50, or $2.50 per unit sold under the rebate program.

- Rebate Marketing Expense. Many mail-in rebates today are distributed either on or in the packaging of the product, or they can be located online. This tends to minimize (but not eliminate) the marketing expenses associated with creation, distribution, and redemption. The rebate marketing expense is commonly averaged across the increase in sales that results from the rebate issuance and not the number or rebates redeemed. Therefore, if a company has $100,000 in rebate marketing expenses, a direct increase in sales by 20,000 units, and only 1,000 rebates redeemed, the rebate marketing expense is \(\$ 100,000 \div 20,000=\$ 5.00\) per unit under the rebate program (note that the rebates redeemed is irrelevant to this calculation).

The Formula

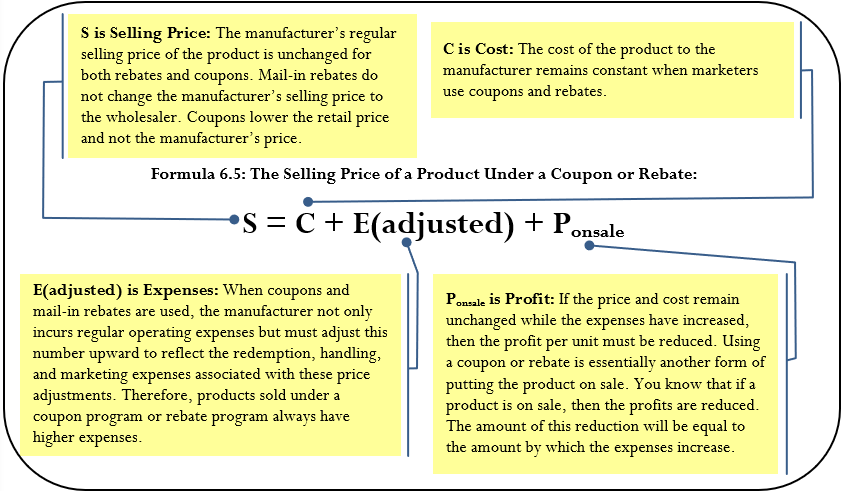

With coupons and rebates, the focus is on how these marketing tools affect expenses and profit. You do not require any new formula; instead, Formula 6.5 is adapted to reflect the pricing impact of these tactics.

How It Works

Follow these steps to calculate the selling price or any of its components when working with coupons or rebates:

Step 1: Identify the known components involved in the selling price, such as the cost, unit expense, profit, or selling price. Use any formulas needed to calculate any of these components. Also identify information about the coupon or rebate, including redemption, handling, and marketing expenses.

Step 2: Calculate the unit expense associated with the marketing pricing tactic.

- Coupons. The unit redemption expense is equal to the face value of the coupon. The unit handling expense is the promised handling fee of the coupon. The unit marketing expense is a simple average of the total marketing expense divided by the expected number of coupon redemptions. Calculate the total coupon expenses by summing all three elements.

- Rebates. The unit redemption expense is equal to the face value of the coupon multiplied by the redemption rate of the rebate. The unit marketing expense is equal to a simple average of the total marketing expense divided by the expected increase in sales as a result of the rebate. Calculate the total rebate expenses by summing both elements.

Step 3: Apply the required merchandising formulas to calculate the unknown variable(s). The modified Formula 6.5 presented earlier will most likely play prominently in these calculations.

Quick Coupon Example

Assume a manufacturer coupon is issued with a face value of $5. The handling charge is $0.15 per coupon. The marketing expenses are estimated at $150,000, and the company forecasts that 100,000 coupons will be redeemed. The regular profit on the product is $20. How much will the unit expenses of the product increase, and what is the unit profit under the coupon program?

Step 1: You know the following information: \(P\) = $20, Face Value = $5, Handling Charge = $0.15; Total Marketing Expenses = $150,000, and Forecasted Coupon Redemption = 100,000.

Step 2: The increase in expenses is a sum of the redemption, handling, and marketing expenses. The redemption expense is $5. The handling expense is $0.15. To get the marketing expense per unit, take the total expense and divide it by the number of redemptions expected. Therefore \(\$ 150,000 \div 100,000=\$ 1.50\). The total increase in expenses is then \(\$ 5.00+\$ 0.15+\$ 1.50=\$ 6.65\).

Step 3: If the expenses rise by $6.65 with the same cost and selling price, then the profits fall by the same amount. The unit profit on any product sold using the coupon is \(\$ 20.00-\$ 6.65=\$ 13.35\).

Quick Rebate Example

Assume a manufacturer mail-in rebate is issued with a face value of $20. The marketing expenses are estimated at $300,000 and the company plans on 10% of the mail-in rebates being redeemed. It is forecasted that sales will rise by 37,500 units as a result of the mail-in rebate. The regular profit on the product is $25. How much will the unit expenses of the product increase, and what is the unit profit under the rebate program?

Step 1: You know the following information: \(P\)= $25, Face Value = $20, Total Marketing Expenses = $300,000, Rebate Redemption Rate = 10%, and Increase in Sales = 37,500.

Step 2: The increase in expenses is a sum of the redemption and marketing expenses. The redemption expense is $20.00 multiplied by the 10% redemption rate, or $2. To calculate the marketing expense per unit, take the total expense and divide it by the increase in sales. Therefore \(\$ 300,000 \div 37,500=\$ 8\). The total increase in expenses is then \(\$ 2+\$ 8=\$ 10\).

Step 3: If the expenses rise by $10 with the same cost and selling price, then the profits fall by the same amount. The unit profit on any product sold using the coupon is \(\$ 25-\$ 10=\$ 15\).

Things To Watch Out For

When calculating the per-unit expense, be careful to distinguish how to handle the various associated expenses for both manufacturer coupons and mail-in rebates, as summarized in the table below.

| Marketing Tactic | Redemption Expense | Handling Expense | Marketing Expense |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupon | Face value of the coupon | A flat rate per coupon | The total expense divided by the number of coupons redeemed |

| Mail-In Rebate | Face value of the mail-in rebate multiplied by the redemption rate | N/A | The total expense divided by the increase in sales attributed to the mail-in rebate |

Paths To Success

It pays to be smart when you deal with coupons and mail-in rebates as a consumer. Two important considerations are timing and hassle.

- Timing. Coupon amounts are usually smaller than rebate amounts. You may be offered a $35 coupon (sometimes called an “instant rebate,” but should not be confused with rebates) at the cash register, or a $50 mail-in rebate. If you choose the former, you get the price savings immediately. If you choose the latter, you must spend the money up front and then wait 8 to 12 weeks (or more) to receive your rebate cheque.

- Hassle. Mail-in rebates are subject to very strict rules for redemption. Most require original proofs of purchase such as your original cash register receipts, UPC codes, model numbers, and serial numbers (which are difficult to find sometimes). You must photocopy these for your records in the event there is a rebate problem. Specific dates of purchase and deadlines for redemption must be met. Some rebates, particularly computer software upgrades, even require you to send your old CD-ROM in with your purchase, substantially raising your postage and envelope costs. Does all that extra time and cost justify the rebate? For example, Benylin ran a sales promotion offering an instant coupon for $1; alternatively you could purchase two products and mail-in two UPC codes for a $3 rebate. When factoring in costs for postage, envelope, photocopying, and time, the benefit from the mail-in rebate is marginal at best.

What happens to the unit profit when a coupon or rebate is issued under the following scenarios:

- The cost remains the same and the selling price increases

- Answer

-

- Profit decreases by the total unit expenses associated with the coupon or rebate.

- Profit decreases by the sum of the total unit expenses associated with the coupon or rebate and the amount of the increased cost together.

- Profit decreases by the sum of the total unit expenses associated with the coupon or rebate and increases by the amount of the price increase.

- Profit decreases by the total unit expenses associated with the coupon or rebate and the amount of the increased cost together.

When the DVD edition of the Bee Movie was released in retail stores, DreamWorks Animation executed a coupon marketing program. Assume the unit cost of the DVD is $2.50, the normal expenses associated with the DVD amount to $1.25, and that DreamWorks sells it directly to retailers for $10. The coupon offered a $3 savings on the DVD to consumers and promised the retailer an $0.08 handling fee per coupon redeemed. The estimated costs of creating, distributing, and redeeming the coupons are $285,000, and the projected number of coupons redeemed is 300,000.

- What is the unit profit of the DVD when it sold without the coupon?

- What unit profit did DreamWorks realize for those DVDs sold under its coupon promotion?

Solution

You need to first calculate the profit (\(P\)) when no coupon was available. Second, you will calculate the impact of the coupon on the profit when the DVD is discounted under the coupon program (\(P_{onsale}\)).

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The unit cost of the DVD along with its normal associated expenses and regular unit selling price are known. The coupon details are:

\(C = \$2.50, E = \$1.25, S = \$10.00\)

Face Value = $3

Handling Fee = $0.08

Total Marketing Expense = $285,000

Number of Redeemed Coupons = 300,000

How You Will Get There

Step 2:

When the coupon is issued, the expenses associated with the DVD rise to accommodate the coupon redemption expense, the handling expense, and the marketing expenses.

Step 3:

Calculate the profit normally realized on the DVD by applying Formula 6.5, rearranging for \(P\).

Step 3 (continued):

Recalculate the profit under the coupon program by adapting Formula 6.5, rearranging for (\(P_{onsale}\)).

Perform

Step 2:

\[\text { Unit coupon expense }=\$ 3+\$ 0.08+(\$ 285,000 \div 300,000)=\$ 4.03 \nonumber \]

Step 3:

\[\begin{aligned}

\$ 10.00&=\$ 2.50+\$ 1.25+P \\

\$ 6.25&=P

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Step 3 (continued):

\[\begin{aligned}

\$ 10.00 &=\$ 2.50+(\$ 1.25+\$ 4.03)+P_{onsale} \\

\$ 10.00 &=\$ 7.78+P_{onsale} \\

\$ 2.22 &=P_{onsale}

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Without the coupon promotion a Bee Movie DVD generates $6.25 in profit. Under the coupon promotion, DreamWorks achieves a reduced profit per DVD of $2.22.

Computer manufacturers commonly issue rebates on items such as printers and monitors. Assume LG decided to distribute its new 22” widescreen LCD monitor (MSRP: $329.99) with a prepackaged mail-in rebate included inside the box. The rebate is $75. The company predicts a 25% rebate redemption rate. Its unit cost to produce the monitor is $133.75, with expenses equaling 35% of cost. It sells the monitor directly to retailers for a regular unit selling price of $225. The increased marketing expenses for promotion and rebate redemption equal $8.20 per monitor. What is the profit for a monitor sold through the rebate program?

Solution

You are looking for the profit ((\(P_{onsale}\))) for a monitor sold under the rebate program. This profit must factor in the rebate face value, redemption rate, and marketing expenses.

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The unit cost, unit expenses, and regular unit selling price are known. The rebate details are:

\(C = \$133.75, E = 0.35C, S = \$225.00\)

Face Value = $75

Redemption rate = 25%

Unit Marketing Expenses = $8.20

How You Will Get There

Step 2:

When the rebate is issued, the expenses associated with the monitor rise to accommodate the rebate redemption expenses and the marketing expenses.

Step 3:

Apply an adjusted Formula 6.5, rearranging for (\(P_{onsale}\)).

Step 2:

\[\text { Unit rebate expense }=\$ 75 \times 25 \%+\$ 8.20=\$ 18.75+8.20=\$ 26.95 \nonumber \]

Step 3:

\[\begin{aligned}

\$ 225.00 &=\$ 133.75+(\$ 46.81+\$ 26.95)+P_{onsale} \\

\$ 225.00 &=\$ 207.51+P_{onsale} \\

\$ 17.49 &=P_{onsale}

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

The rebate redemption expense for the LG monitor is $18.75. LG averages a profit of $17.49 per monitor sold under its mail-in rebate program.