10.7: Volume and Surface Area

- Page ID

- 129646

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Calculate the surface area of right prisms and cylinders.

- Calculate the volume of right prisms and cylinders.

- Solve application problems involving surface area and volume.

Volume and surface area are two measurements that are part of our daily lives. We use volume every day, even though we do not focus on it. When you purchase groceries, volume is the key to pricing. Judging how much paint to buy or how many square feet of siding to purchase is based on surface area. The list goes on. An example is a three-dimensional rendering of a floor plan. These types of drawings make building layouts far easier to understand for the client. It allows the viewer a realistic idea of the product at completion; you can see the natural space, the volume of the rooms. This section gives you practical information you will use consistently. You may not remember every formula, but you will remember the concepts, and you will know where to go should you want to calculate volume or surface area in the future.

We will concentrate on a few particular types of three-dimensional objects: right prisms and right cylinders. The adjective “right” refers to objects such that the sides form a right angle with the base. We will look at right rectangular prisms, right triangular prisms, right hexagonal prisms, right octagonal prisms, and right cylinders. Although, the principles learned here apply to all right prisms.

Three-Dimensional Objects

In geometry, three-dimensional objects are called geometric solids. Surface area refers to the flat surfaces that surround the solid and is measured in square units. Volume refers to the space inside the solid and is measured in cubic units. Imagine that you have a square flat surface with width and length. Adding the third dimension adds depth or height, depending on your viewpoint, and now you have a box. One way to view this concept is in the Cartesian coordinate three-dimensional space. The \(x\)-axis and the \(y\)-axis are, as you would expect, two dimensions and suitable for plotting two-dimensional graphs and shapes. Adding the \(z\)-axis, which shoots through the origin perpendicular to the \(x y\)-plane, and we have a third dimension. See Figure .

Here is another view taking the two-dimensional square to a third dimension. See Figure .

To study objects in three dimensions, we need to consider the formulas for surface area and volume. For example, suppose you have a box (Figure ) with a hinged lid that you want to use for keeping photos, and you want to cover the box with a decorative paper. You would need to find the surface area to calculate how much paper is needed. Suppose you need to know how much water will fill your swimming pool. In that case, you would need to calculate the volume of the pool. These are just a couple of examples of why these concepts should be understood, and familiarity with the formulas will allow you to make use of these ideas as related to right prisms and right cylinders.

Right Prisms

A right prism is a particular type of three-dimensional object. It has a polygon-shaped base and a congruent, regular polygon-shaped top, which are connected by the height of its lateral sides, as shown in Figure . The lateral sides form a right angle with the base and the top. There are rectangular prisms, hexagonal prisms, octagonal prisms, triangular prisms, and so on.

Generally, to calculate surface area, we find the area of each side of the object and add the areas together. To calculate volume, we calculate the space inside the solid bounded by its sides.

The formula for the surface area of a right prism is equal to twice the area of the base plus the perimeter of the base times the height, \(S A=2 B+p h\), where \(B\) is equal to the area of the base and top, \(p\) is the perimeter of the base, and \(h\) is the height.

The formula for the volume of a rectangular prism, given in cubic units, is equal to the area of the base times the height, \(V=B \cdot h\), where \(B\) is the area of the base and \(h\) is the height.

Find the surface area and volume of the rectangular prism that has a width of 10 cm, a length of 5 cm, and a height of 3 cm (Figure ).

- Answer

-

The surface area is \(S A=2(10)(5)+2(5)(3)+2(10)(3)=190 \mathrm{~cm}^2\).

The volume is \(V=10(5)(3)=150 \mathrm{~cm}^3\).

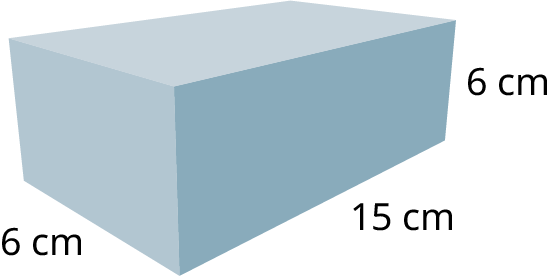

A rectangular solid has a width of 6 cm, length of 15 cm, and height or depth of 6 cm. Find the surface area and the volume.

In Figure 10.129, we have three views of a right hexagonal prism. The regular hexagon is the base and top, and the lateral faces are the rectangular regions perpendicular to the base. We call it a right prism because the angle formed by the lateral sides to the base is \(90^{\circ}\). See Figure

The first image is a view of the figure straight on with no rotation in any direction. The middle figure is the base or the top. The last figure shows you the solid in three dimensions. To calculate the surface area of the right prism shown in Figure 10.129, we first determine the area of the hexagonal base and multiply that by 2, and then add the perimeter of the base times the height. Recall the area of a regular polygon is given as \(A=\frac{1}{2} a p\), where \(a\) is the apothem and \(p\) is the perimeter. We have that

\[A_{\text {base }}=\frac{1}{2}(5.2)(36)=93.6 \mathrm{~cm}^2 \nonumber \]

Then, the surface area of the hexagonal prism is

\[S A=2(93.6)+36(20)=907.2 \text { in }^2 \nonumber \]

To find the volume of the right hexagonal prism, we multiply the area of the base by the height using the formula \(V=B h\). The base is \(93.6 \mathrm{~cm}^2\), and the height is 20 cm . Thus,

\[V=93.6(20)=1872 \mathrm{~cm}^3 \nonumber \]

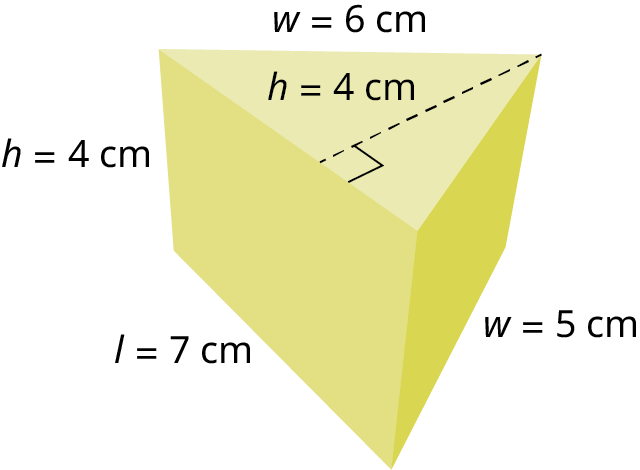

Find the surface area of the triangular prism (Figure ).

- Answer

-

The area of the triangular base is \(A_{\text {base }}=\frac{1}{2}(12)(6)=36 \mathrm{in}^2\). The perimeter of the base is \(p=12+8.49+8.49=28.98 \mathrm{in}\). Then, the surface area of the triangular prism is \(S A=2(36)+28.98(10)=361.8 \mathrm{in}^2\).

Find the surface area of the triangular prism shown.

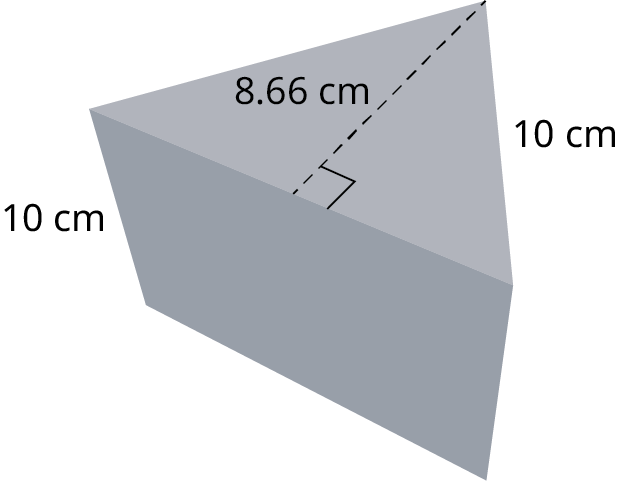

Find the surface area and the volume of the right triangular prism with an equilateral triangle as the base and height (Figure ).

- Answer

-

The area of the triangular base is \(A_{\text {base }}=\frac{1}{2}(6)(10.39)=31.17 \mathrm{~cm}^2\). Then, the surface area is \(S A=2(31.17)+36(10)=422.34 \mathrm{~cm}^2\).

The volume formula is found by multiplying the area of the base by the height. We have that \(V=B \cdot h=(31.17)(10)=311.7 \mathrm{~cm}^3\).

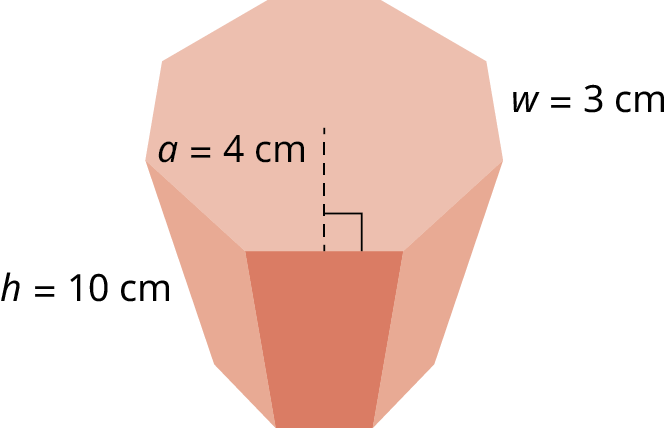

Find the surface area and the volume of the octagonal figure shown.

Katherine and Romano built a greenhouse made of glass with a metal roof (Figure ). In order to determine the heating and cooling requirements, the surface area must be known. Calculate the total surface area of the greenhouse.

- Answer

-

The area of the long side measures \(95 \mathrm{ft} \times 6.5 \mathrm{ft}=1,235 \mathrm{ft}^2\). Multiplying by 2 gives \(2,470 \mathrm{ft}^2\). The front (minus the triangular area) measures \(22 \mathrm{ft} \times 6.5 \mathrm{ft}=286 \mathrm{ft}^2\). Multiplying by 2 gives \(572 \mathrm{ft}^2\). The floor measures \(95 \mathrm{ft} \times 22 \mathrm{ft}=2,090 \mathrm{ft}^2\). Each triangular region measures \(A=\frac{1}{2}(22)(5)=55 \mathrm{ft}^2\). Multiplying by 2 gives \(110 \mathrm{ft}^2\). Finally, one side of the roof measures \(12.1 \mathrm{ft} \times 95 \mathrm{ft}=1,149.5 \mathrm{ft}^2\). Multiplying by 2 gives \(2299 \mathrm{ft}^2\). Add them up and we have \(S A=2,470+572+2,090+110+2,299=7,541 \mathrm{ft}^2\).

Calculate the surface area of a greenhouse with a flat roof measuring 12 ft wide, 25 ft long, and 8 ft high.

Right Cylinders

There are similarities between a prism and a cylinder. While a prism has parallel congruent polygons as the top and the base, a right cylinder is a three-dimensional object with congruent circles as the top and the base. The lateral sides of a right prism make a angle with the polygonal base, and the side of a cylinder, which unwraps as a rectangle, makes a angle with the circular base.

Right cylinders are very common in everyday life. Think about soup cans, juice cans, soft drink cans, pipes, air hoses, and the list goes on.

In Figure , imagine that the cylinder is cut down the 12-inch side and rolled out. We can see that the cylinder side when flat forms a rectangle. The

The surface area of a right cylinder is given as \(S A=2 \pi r^2+2 \pi r h\).

To find the volume of the cylinder, we multiply the area of the base with the height.

The volume of a right cylinder is given as \(V=\pi r^2 h\).

Given the cylinder in Figure , which has a radius of 5 inches and a height of 12 inches, find the surface area and the volume.

- Answer

-

Step 1: We begin with the areas of the base and the top. The area of the circular base is

\[A_{b a s e}=\pi(5)^2=25 \pi=78.5 \mathrm{in}^2 \nonumber \]

Step 2: The base and the top are congruent parallel planes. Therefore, the area for the base and the top is

\[A=2(78.5)=157 \mathrm{in}^2 \nonumber \]

Step 3: The area of the rectangular side is equal to the circumference of the base times the height:

\[A=2 \pi(5)(12)=377 \mathrm{in}^2 \nonumber \]

Step 4: We add the area of the side to the areas of the base and the top to get the total surface area. We have

\[S A=157+377=534 \text { in }^2 \nonumber \]

Step 5: The volume is equal to the area of the base times the height. Then,

\[V=\pi(5)^2(12)=942.48 \mathrm{in}^3 \nonumber \]

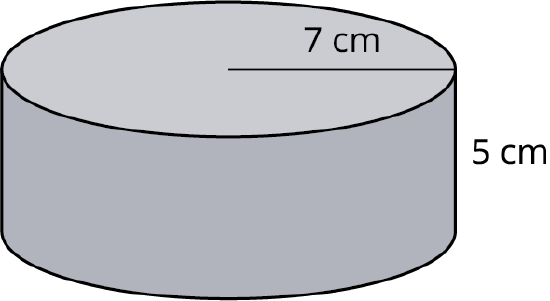

Find the surface area and volume of the cylinder with a radius of 7cm and a height of 5 cm.

Applications of Surface Area and Volume

The following are just a small handful of the types of applications in which surface area and volume are critical factors. Give this a little thought and you will realize many more practical uses for these procedures.

A can of apple pie filling has a radius of 4 cm and a height of 10 cm. How many cans are needed to fill a pie pan (Figure ) measuring 22 cm in diameter and 3 cm deep?

- Answer

-

The volume of the can of apple pie filling is The volume of the pan is To find the number of cans of apple pie filling, we divide the volume of the pan by the volume of a can of apple pie filling. Thus, We will need 2.3 cans of apple pie filling to fill the pan.

You are making a casserole that includes vegetable soup and pasta. The size of your cylindrical casserole dish has a diameter of 10 inches and is 4 inches high. The pasta will consume the bottom portion of the casserole dish about 1 inch high. The soup can has a diameter of 3 inches and is 4 inches high. After the pasta is added, how many cans of soup can you add?

Optimization

Problems that involve optimization are ones that look for the best solution to a situation under some given conditions. Generally, one looks to calculus to solve these problems. However, many geometric applications can be solved with the tools learned in this section. Suppose you want to make some throw pillows for your sofa, but you have a limited amount of fabric. You want to make the largest pillows you can from the fabric you have, so you would need to figure out the dimensions of the pillows that will fit these criteria. Another situation might be that you want to fence off an area in your backyard for a garden. You have a limited amount of fencing available, but you would like the garden to be as large as possible. How would you determine the shape and size of the garden? Perhaps you are looking for maximum volume or minimum surface area. Minimum cost is also a popular application of optimization. Let’s explore a few examples.

Suppose you have 150 meters of fencing that you plan to use for the enclosure of a corral on a ranch. What shape would give the greatest possible area?

- Answer

-

So, how would we start? Let’s look at this on a smaller scale. Say that you have 30 inches of string and you experiment with different shapes. The rectangle in Figure measures 12 in long by 3 in wide. We have a perimeter of

30 in 30 in 30 in 2 π r , 30 = 2 π r , 30 ÷ 2 π = 4.77 in 30 ÷ 2 π = 4.77 in Figure

We see that the circular shape gives the maximum area relative to a circumference of 30 in. So, a circular corral with a circumference of 150 meters and a radius of 23.87 meters gives a maximum area of

You have 25 ft of rope to section off a rectangular-shaped garden. What dimensions give the maximum area that can be roped off?

Suppose you want to design a crate built out of wood in the shape of a rectangular prism (Figure ). It must have a volume of 3 cubic meters. The cost of wood is $15 per square meter. What dimensions give the most economical design while providing the necessary volume?

- Answer

-

To choose the optimal shape for this container, you can start by experimenting with different sizes of boxes that will hold 3 cubic meters. It turns out that, similar to the maximum rectangular area example where a square gives the maximum area, a cube gives the maximum volume and the minimum surface area.

As all six sides are the same, we can use a simplified volume formula:

\[V=s^3 \nonumber \]

where \(s\) is the length of a side. Then, to find the length of a side, we take the cube root of the volume.

We have\[\begin{aligned}

3 & =s^3 \\

\sqrt[3]{3} & =s \\

& =1.4422 \mathrm{~m}

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]The surface area is equal to the sum of the areas of the six sides. The area of one side is \(A=(1.4422)^2=2.08 \mathrm{~m}^2\). So, the surface area of the crate is \(S A=6(2.08)=12.5 \mathrm{~m}^2\). At \(\$ 15\) a square meter, the cost comes to \(12.5(\$ 15)=\$ 187.50\). Checking the volume, we have \(V=(1.4422)^3=2.99 \mathrm{~m}^3\).

Suppose you want to a build a container to hold 2 cubic feet of fabric swatches. You want to cover the container in laminate costing $10 per square foot. What are the dimensions of the container that is the most economical? What is the cost?

Check Your Understanding

1. Find the surface area of the equilateral triangular prism shown.

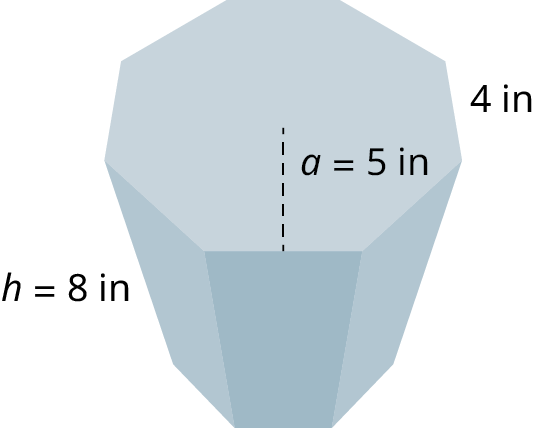

2. Find the surface area of the octagonal prism shown.

3. Find the volume of the octagonal prism shown with the apothem equal to \(5\,\text{in},\) the side length equal to \(4\,\text{in},\) and the height equal to \(8\,\text{in}.\)

4. Determine the surface area of the right cylinder where the radius of the base is \(10\,\text{cm}\), and the height is \(5\,\text{cm}\).

5. Find the volume of the cylinder where the radius of the base is \(10\,\text{cm}\), and the height is \(5\,\text{cm}\).

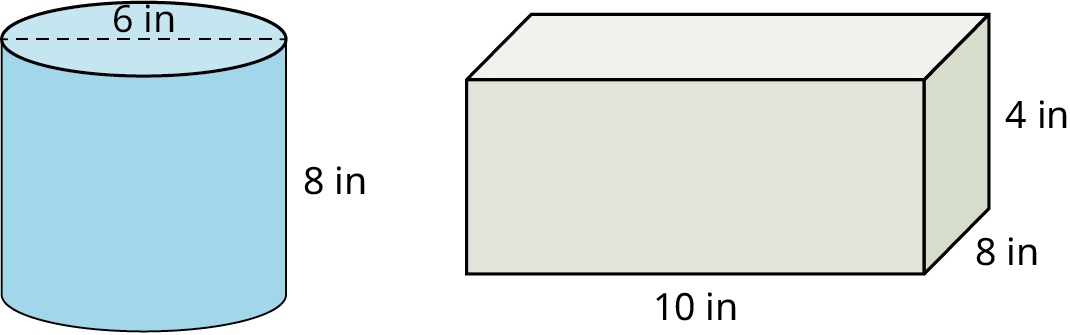

6. As an artist, you want to design a cylindrical container for your colored art pencils and another rectangular container for some other tools. The cylindrical container will be 8 inches high with a diameter of 6 inches. The rectangular container measures 10 inches wide by 8 inches deep by 4 inches high and has a lid. You found some beautiful patterned paper to use to wrap both pieces. How much paper will you need?