Learning Objectives

In this section, we strive to understand the ideas generated by the following important questions:

- What are the critical numbers of a function f and how are they connected to identifying the most extreme values the function achieves?

- How does the first derivative of a function reveal important information about the behavior of the function, including the function’s extreme values?

- How can the second derivative of a function be used to help identify extreme values of the function?

In many different settings, we are interested in knowing where a function achieves its least and greatest values. These can be important in applications – say to identify a point at which maximum profit or minimum cost occurs – or in theory to understand how to characterize the behavior of a function or a family of related functions. Consider the simple and familiar example of a parabolic function such as

which is shown at left in Figure and that represents the height of an object tossed vertically: its maximum value occurs at the vertex of the parabola and represents the highest value that the object reaches. Moreover, this maximum value identifies an especially important point on the graph, the point at which the curve changes from increasing to decreasing. More generally, for any function we consider, we can investigate where its lowest

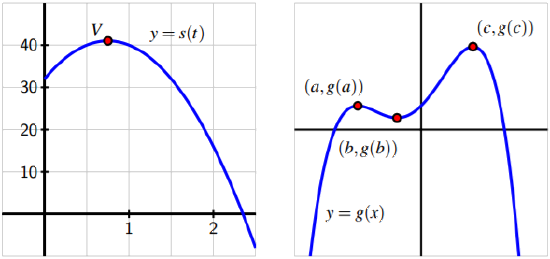

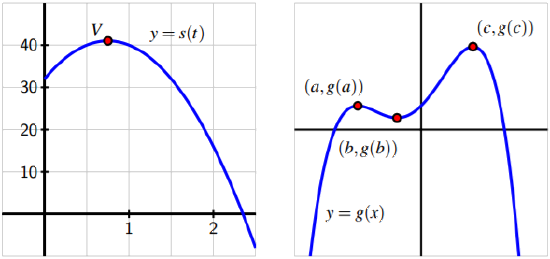

Figure : At left, whose vertex is ; at right, a function that demonstrates several high and low points.

and highest points occur in comparison to points nearby or to all possible points on the graph. Given a function , we say that is a global or absolute maximum provided that for all in the domain of , and similarly call a global or absolute minimum whenever for all x in the domain of f . For instance, for the function g given at right in Figure , has a global maximum of , but does not appear to have a global minimum, as the graph of g seems to decrease without bound. We note that the point marks a fundamental change in the behavior of , where changes from increasing to decreasing; similar things happen at both and , although these points are not global mins or maxes.

For any function , we say that is a local maximum or relative maximum provided that for all x near c, while f (c) is called a local or relative minimum whenever for all near . Any maximum or minimum may be called an extreme value of . For example, in Figure , g has a relative minimum of g(b) at the point and a relative maximum of at . We have already identified the global maximum of as ; this global maximum can also be considered a relative maximum.

We would like to use fundamental calculus ideas to help us identify and classify key function behavior, including the location of relative extremes. Of course, if we are given a graph of a function, it is often straightforward to locate these important behaviors visually. We investigate this situation in the following preview activity.

Preview Activity

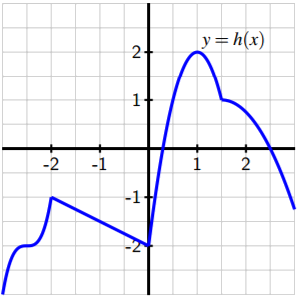

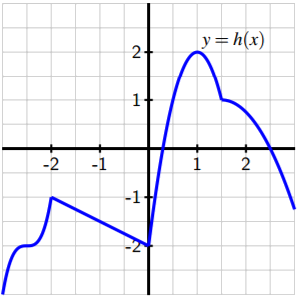

Consider the function h given by the graph in Figure . Use the graph to answer each of the following questions.

Figure : The graph of a function h on the interval [−3, 3].

- Identify all of the values of for which is a local maximum of .

- Identify all of the values of for which is a local minimum of .

- Does h have a global maximum on the interval ? If so, what is the value of this global maximum?

- Does h have a global minimum on the interval ? If so, what is its value?

- Identify all values of for which .

- Identify all values of for which does not exist.

- True or false: every relative maximum and minimum of occurs at a point where is either zero or does not exist.

- True or false: at every point where is zero or does not exist, has a relative maximum or minimum.

Critical numbers and the First Derivative Test

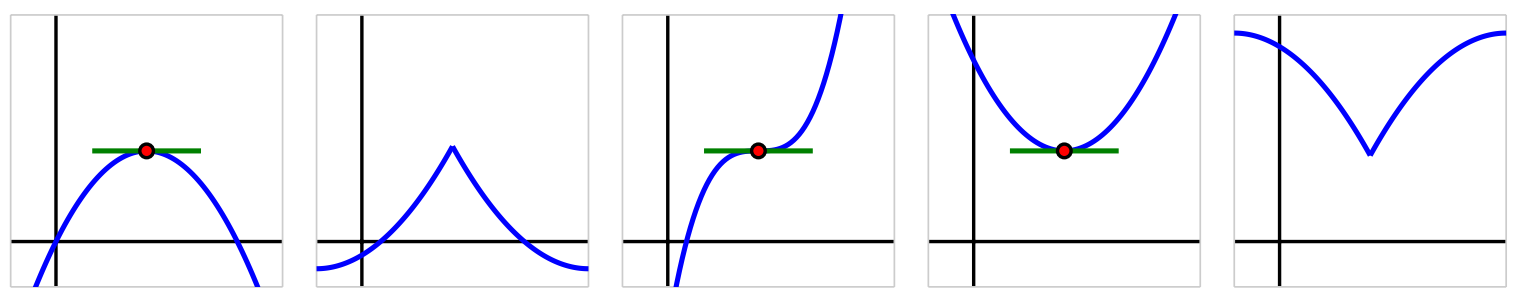

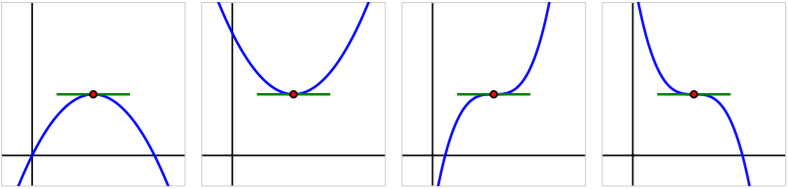

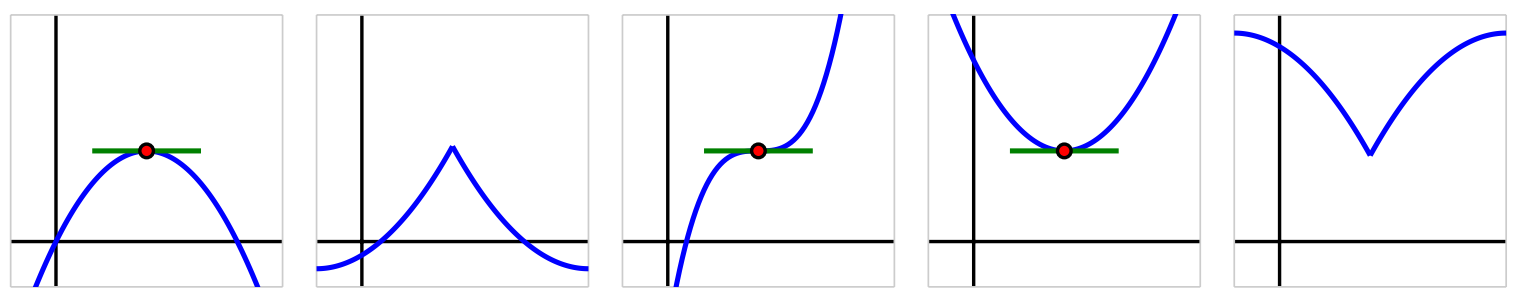

If a function has a relative extreme value at a point , the function must change its behavior at c regarding whether it is increasing or decreasing before or after the point. For example, if a continuous function has a relative maximum at , such as those pictured in the two leftmost functions in Figure , then it is both necessary and sufficient that the function change from being increasing just before to decreasing just after . In the same way, a continuous function has a relative minimum at c if and only if the function changes from decreasing to increasing at . See, for instance, the two functions pictured at right in Figure . There are only two possible ways for these changes in behavior to occur: either or is undefined.

Figure : From left to right, a function with a relative maximum where its derivative is zero; a function with a relative maximum where its derivative is undefined; a function with neither a maximum nor a minimum at a point where its derivative is zero; a function with a relative minimum where its derivative is zero; and a function with a relative minimum where its derivative is undefined.

Because these values of are so important, we call them critical numbers. More specifically, we say that a function has a critical number at provided that is in the domain of , and or is undefined. Critical numbers provide us with the only possible locations where the function f may have relative extremes. Note that not every critical number produces a maximum or minimum; in the middle graph of Figure , the function pictured there has a horizontal tangent line at the noted point, but the function is increasing before and increasing after, so the critical number does not yield a location where the function is greater than every value nearby, nor less than every value nearby.

We also sometimes use the terminology that, when is a critical number, that is a critical point of the function, or that is a critical value.

The first derivative test summarizes how sign changes in the first derivative indicate the presence of a local maximum or minimum for a given function.

First Derivative Test

If is a critical number of a continuous function that is differentiable near (except possibly at ), then f has a relative maximum at if and only if changes sign from positive to negative at , and has a relative minimum at if and only if changes sign from negative to positive at .

We consider an example to show one way the first derivative test can be used to identify the relative extreme values of a function.

Example :

Let be a function whose derivative is given by the formula . Determine all critical numbers of and decide whether a relative maximum, relative minimum, or neither occurs at each.

Solution

Since we already have written in factored form, it is straightforward to find the critical numbers of . Since f' (x) is defined for all values of x, we need only 165 determine where f' (x) = 0. From the equation

and the zero product property, it follows that and are critical numbers of . (Note particularly that there is no value of that makes .)

Next, to apply the first derivative test, we’d like to know the sign of at inputs near the critical numbers. Because the critical numbers are the only locations at which f' can change sign, it follows that the sign of the derivative is the same on each of the intervals created by the critical numbers: for instance, the sign of f' must be the same for every . We create a first derivative sign chart to summarize the sign of f' on the relevant intervals along with the corresponding behavior of f .

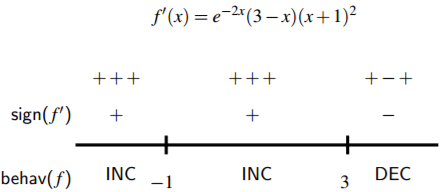

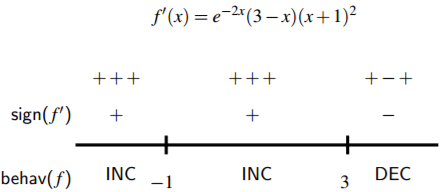

Figure : The first derivative sign chart for a function f whose derivative is given by the formula f' (x) = e −2x (3 − x)(x + 1) 2 .

The first derivative sign chart in Figure comes from thinking about the sign of each of the terms in the factored form of at one selected point in the interval under consideration. For instance, for , we could consider and determine the sign of , , and at the value . We note that both and are positive regardless of the value of x, while is also positive at . Hence, each of the three terms in is positive, which we indicate by writing “+ + +.” Taking the product of three positive terms obviously results in a value that is positive, which we denote by the “+” in the interval to the left of x = −1 indicating the overall sign of . And, since is positive on that interval, we further know that is increasing, which we summarize by writing “INC” to represent the corresponding behavior of . In a similar way, we find that is positive and is increasing on , and is negative and is decreasing for .

Now, by the first derivative test, to find relative extremes of we look for critical numbers at which changes sign. In this example, only changes sign at , where changes from positive to negative, and thus has a relative maximum at . While f has a critical number at , since is increasing both before and after , has neither a minimum nor a maximum at x = −1.

Activity

Suppose that is a function continuous for every value of whose first derivative is

Further, assume that it is known that g has a vertical asymptote at .

- Determine all critical numbers of .

- By developing a carefully labeled first derivative sign chart, decide whether has as a local maximum, local minimum, or neither at each critical number.

- Does g have a global maximum? global minimum? Justify your claims.

- What is the value of ? What does the value of this limit tell you about the long-term behavior of ?

- Sketch a possible graph of .

The Second Derivative Test

Recall that the second derivative of a function tells us several important things about the behavior of the function itself. For instance, if is positive on an interval, then we know that is increasing on that interval and, consequently, that f is concave up, which also tells us that throughout the interval the tangent line to lies below the curve at every point. In this situation where we know that , it turns out that the sign of the second derivative determines whether has a local minimum or local maximum at the critical number .

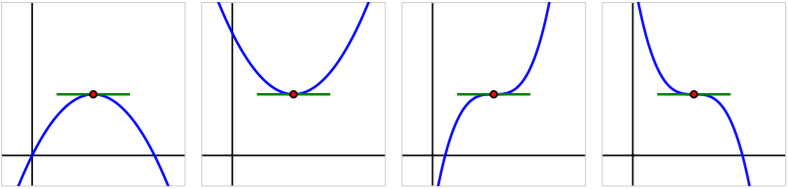

In Figure , we see the four possibilities for a function that has a critical number at which , provided is not zero on an interval including p (except possibly at ). On either side of the critical number, ' can be either positive or negative, and hence can be either concave up or concave down. In the first two graphs, does not change concavity at , and in those situations, has either a local minimum or local maximum. In particular, if and , then we know f is concave down at with a horizontal tangent line, and this guarantees has a local maximum there. This fact, along with the corresponding statement for when is positive, is stated in the second derivative test.

Figure : Four possible graphs of a function with a horizontal tangent line at a critical point.

Second Derivative Test

If is a critical number of a continuous function such that and , then has a relative maximum at if and only if , and has a relative minimum at if and only if .

In the event that , the second derivative test is inconclusive. That is, the test doesn’t provide us any information. This is because if , it is possible that f has a local minimum, local maximum, or neither.1 Just as a first derivative sign chart reveals all of the increasing and decreasing behavior of a function, we can construct a second derivative sign chart that demonstrates all of the important information involving concavity.

Example :

Let f (x) be a function whose first derivative is

Construct both first and second derivative sign charts for , fully discuss where is increasing and decreasing and concave up and concave down, identify all relative extreme values, and sketch a possible graph of .

Solution

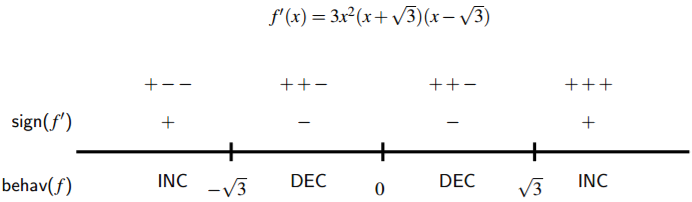

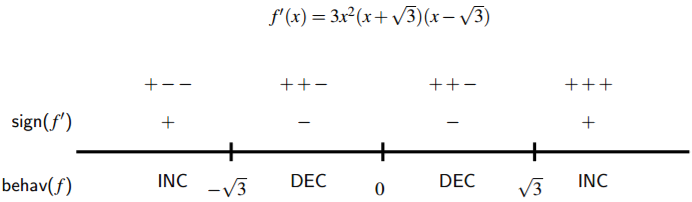

Since we know , we can find the critical numbers of f by solving . Factoring, we observe that

so that are the three critical numbers of . It then follows that the first derivative sign chart for f is given in Figure . Thus, is increasing on the intervals (−∞, − √ 3) and ( √ 3, ∞), while is decreasing on (− √ 3, 0) and (0, √ 3). Note particularly that by the first derivative test, this information tells us that f has a local maximum at 1Consider the functions , g(x) = −x 4 , and h(x) = x 3 at the critical point p = 0.

Figure : The first derivative sign chart for f when f' (x) = 3x 4 − 9x 2 = 3x 2 (x 2 − 3).

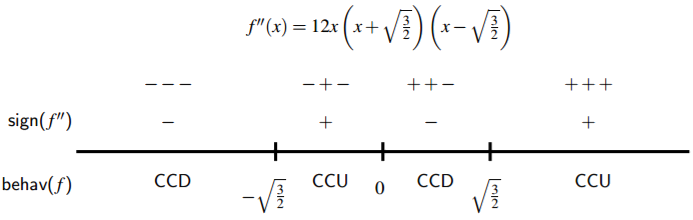

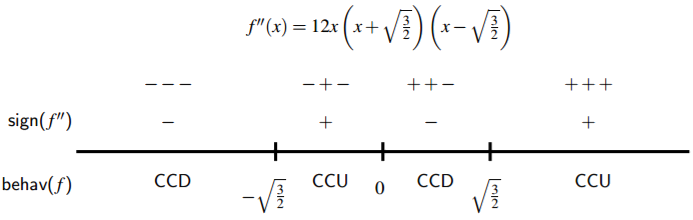

x = − √ 3 and a local minimum at x = √ 3. While f also has a critical number at x = 0, neither a maximum nor minimum occurs there since f' does not change sign at x = 0. Next, we move on to investigate concavity. Differentiating f' (x) = 3x 4 − 9x 2 , we see that f''(x) = 12x 3 − 18x. Since we are interested in knowing the intervals on which f'' is positive and negative, we first find where f''(x) = 0. Observe that 0 = 12x 3 − 18x = 12x x 2 − 3 2 = 12x * , x + r 3 2 + - * , x − r 3 2 + - , which implies that x = 0, ± q 3 2 . Building a sign chart for f'' in the exact same way we do for f' , we see the result shown in Figure . Therefore, f is concave down on the

Figure : The second derivative sign chart for f when f''(x) = 12x 3 − 18x = 12x 2 x 2 − q 3 2 .

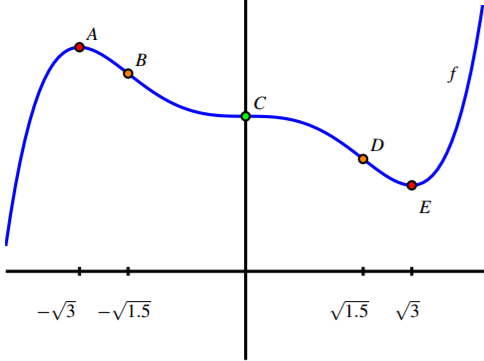

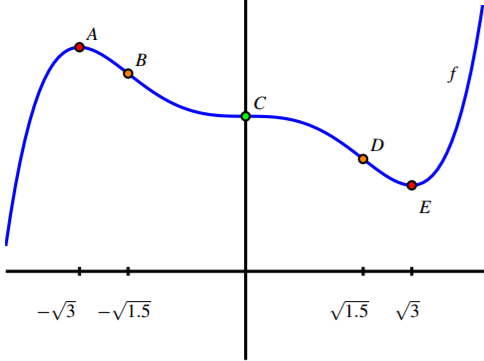

intervals (−∞, − q 3 2 ) and (0, q 3 2 ), and concave up on (− q 3 2 , 0) and ( q 3 2 , ∞). Putting all of the above information together, we now see a complete and accurate 169 possible graph of f in Figure . The point A = (− √ 3, f (− √ 3)) is a local maximum, as f is increasing prior to A and decreasing after; similarly, the point E = ( √ 3, f ( √ 3) is a local minimum.

Figure : A possible graph of the function f in Example 3.2.

Note, too, that f is concave down at A and concave up at B, which is consistent both with our second derivative sign chart and the second derivative test. At points B and D, concavity changes, as we saw in the results of the second derivative sign chart in Figure . Finally, at point , has a critical point with a horizontal tangent line, but neither a maximum nor a minimum occurs there since f is decreasing both before and after .

It is also the case that concavity changes at . While we completely understand where f is increasing and decreasing, where f is concave up and concave down, and where f has relative extremes, we do not know any specific information about the y-coordinates of points on the curve. For instance, while we know that f has a local maximum at x = − √ 3, we don’t know the value of that maximum because we do not know f (− √ 3). Any vertical translation of our sketch of f in Figure would satisfy the given criteria for . Points B, C, and D in Figure are locations at which the concavity of f changes. We give a special name to any such point: if p is a value in the domain of a continuous function at which f changes concavity, then we say that is an inflection point of . Just as we look for locations where f changes from increasing to decreasing at points where or is undefined, so too we find where or is undefined to see if there are points of inflection at these locations. It is important at this point in our study to remind ourselves of the big picture that derivatives help to paint: the sign of the first derivative f' tells us whether the function is increasing or decreasing, while the sign of the second derivative tells us how the function f is increasing or decreasing.

Activity :

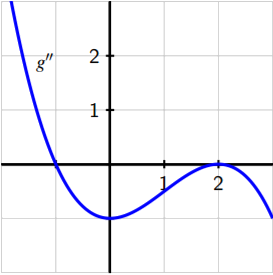

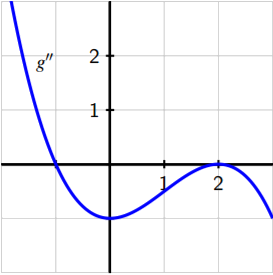

Suppose that is a function whose second derivative, , is given by the following graph.

Figure : The graph of y = g 00(x).

- Find all points of inflection of .

- Fully describe the concavity of by making an appropriate sign chart.

- Suppose you are given that . Is there is a local maximum, local minimum, or neither (for the function ) at this critical point of , or is it impossible to say? Why?

- Assuming that is a polynomial (and that all important behavior of is seen in the graph above, what degree polynomial do you think is? Why?

As we will see in more detail in the following section, derivatives also help us to understand families of functions that differ only by changing one or more parameters. For instance, we might be interested in understanding the behavior of all functions of the form where , , and are numbers that may vary. In the following activity, we investigate a particular example where the value of a single parameter has considerable impact on how the graph appears.

Activity :

Consider the family of functions given by

where is an arbitrary positive real number.

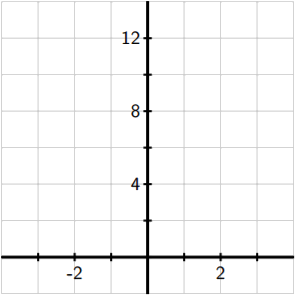

- Use a graphing utility to sketch the graph of h for several different -values, including k = 1, 3, 5, 10. Plot on the axes provided below. What is the smallest value of at which you think you can see (just by looking at the graph) at least one inflection point on the graph of ?

Figure : Axes for plotting y = h(x).

- Explain why the graph of h has no inflection points if , but infinitely many inflection points if .

- Explain why, no matter the value of , can only have finitely many critical numbers.

Summary

In this section, we encountered the following important ideas:

- The critical numbers of a continuous function are the values of for which or does not exist. These values are important because they identify horizontal tangent lines or corner points on the graph, which are the only possible locations at which a local maximum or local minimum can occur.

- Given a differentiable function , whenever is positive, is increasing; whenever is negative, is decreasing. The first derivative test tells us that at any point where changes from increasing to decreasing, has a local maximum, while conversely at any point where changes from decreasing to increasing has a local minimum.

- Given a twice differentiable function , if we have a horizontal tangent line at and is nonzero, then the fact that tells us the concavity of will determine whether f has a maximum or minimum at . In particular, if and , then f is concave down at and has a local maximum there, while if and , then has a local minimum at . If and , then the second derivative does not tell us whether has a local extreme at or not.