11.5: Alternating Series

- Page ID

- 547

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Next we consider series with both positive and negative terms, but in a regular pattern: they alternate, as in the alternating harmonic series for example:

\[ \sum_{n=1}^\infty {(-1)^{n-1}\over n}= {1\over1}+{-1\over2}+{1\over3}+{-1\over4}+\cdots= {1\over1}-{1\over2}+{1\over3}-{1\over4}+\cdots. \nonumber \]

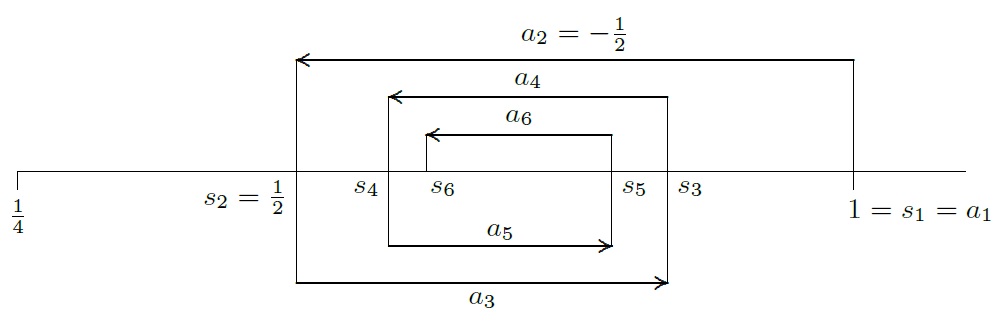

In this series the sizes of the terms decrease, that is, \( |a_n|\) forms a decreasing sequence, but this is not required in an alternating series. As with positive term series, however, when the terms do have decreasing sizes it is easier to analyze the series, much easier, in fact, than positive term series. Consider pictorially what is going on in the alternating harmonic series, shown in Figure 11.4.1. Because the sizes of the terms \( a_n\) are decreasing, the partial sums \( s_1\), \( s_3\), \( s_5\), and so on, form a decreasing sequence that is bounded below by \( s_2\), so this sequence must converge. Likewise, the partial sums \( s_2\), \( s_4\), \( s_6\), and so on, form an increasing sequence that is bounded above by \( s_1\), so this sequence also converges. Since all the even numbered partial sums are less than all the odd numbered ones, and since the "jumps'' (that is, the \( a_i\) terms) are getting smaller and smaller, the two sequences must converge to the same value, meaning the entire sequence of partial sums \( s_1,s_2,s_3,\ldots\) converges as well.

There's nothing special about the alternating harmonic series---the same argument works for any alternating sequence with decreasing size terms. The alternating series test is worth calling a theorem.

Suppose that \(\{a_n\}_{n=1}^\infty\) is a non-increasing sequence of positive numbers and \(\lim_{n\to\infty}a_n=0\). Then the alternating series \(\sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^{n-1} a_n\) converges.

The odd numbered partial sums, \( s_1\), \( s_3\), \( s_5\), and so on, form a non-increasing sequence, because \( s_{2k+3}=s_{2k+1}-a_{2k+2}+a_{2k+3}\le s_{2k+1}\), since \( a_{2k+2}\ge a_{2k+3}\). This sequence is bounded below by \( s_2\), so it must converge, say \(\lim_{k\to\infty}s_{2k+1}=L\). Likewise, the partial sums \( s_2\), \( s_4\), \( s_6\), and so on, form a non-decreasing sequence that is bounded above by \( s_1\), so this sequence also converges, say \(\lim_{k\to\infty}s_{2k}=M\). Since \(\lim_{n\to\infty} a_n=0\) and \( s_{2k+1}= s_{2k}+a_{2k+1}\),

\[ L=\lim_{k\to\infty}s_{2k+1}=\lim_{k\to\infty}(s_{2k}+a_{2k+1})= \lim_{k\to\infty}s_{2k}+\lim_{k\to\infty}a_{2k+1}=M+0=M, \nonumber \]

so \(L=M\), the two sequences of partial sums converge to the same limit, and this means the entire sequence of partial sums also converges to \(L\).

\(\square \)

Another useful fact is implicit in this discussion. Suppose that \(L=\sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^{n-1} a_n\) and that we approximate \(L\) by a finite part of this sum, say \(L\approx \sum_{n=1}^N (-1)^{n-1} a_n.\) Because the terms are decreasing in size, we know that the true value of \(L\) must be between this approximation and the next one, that is, between \(\sum_{n=1}^N (-1)^{n-1} a_n \quad \) and \(\quad \sum_{n=1}^{N+1} (-1)^{n-1} a_n. \) Depending on whether \(N\) is odd or even, the second will be larger or smaller than the first.

Approximate the alternating harmonic series to one decimal place.

Solution

We need to go roughly to the point at which the next term to be added or subtracted is \(1/10\). Adding up the first nine and the first ten terms we get approximately \(0.746\) and \(0.646\). These are \(1/10\) apart, but it is not clear how the correct value would be rounded. It turns out that we are able to settle the question by computing the sums of the first eleven and twelve terms, which give \(0.737\) and \(0.653\), so correct to one place the value is \(0.7\).

We have considered alternating series with first index 1, and in which the first term is positive, but a little thought shows this is not crucial. The same test applies to any similar series, such as \(\sum_{n=0}^\infty (-1)^n a_n\), \(\sum_{n=1}^\infty (-1)^n a_n\), \(\sum_{n=17}^\infty (-1)^n a_n\), etc.

Contributors and Attributions

Integrated by Justin Marshall.