3.5: Derivatives of Trigonometric Functions

- Page ID

- 2494

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Find the derivatives of the sine and cosine function.

- Find the derivatives of the standard trigonometric functions.

- Calculate the higher-order derivatives of the sine and cosine.

One of the most important types of motion in physics is simple harmonic motion, which is associated with such systems as an object with mass oscillating on a spring. Simple harmonic motion can be described by using either sine or cosine functions. In this section we expand our knowledge of derivative formulas to include derivatives of these and other trigonometric functions. We begin with the derivatives of the sine and cosine functions and then use them to obtain formulas for the derivatives of the remaining four trigonometric functions. Being able to calculate the derivatives of the sine and cosine functions will enable us to find the velocity and acceleration of simple harmonic motion.

Derivatives of the Sine and Cosine Functions

We begin our exploration of the derivative for the sine function by using the formula to make a reasonable guess at its derivative. Recall that for a function \(f(x),\)

\[f′(x)=\lim_{h→0}\dfrac{f(x+h)−f(x)}{h}. \nonumber \]

Consequently, for values of \(h\) very close to \(0\),

\[f′(x)≈\dfrac{f(x+h)−f(x)}{h}. \nonumber \]

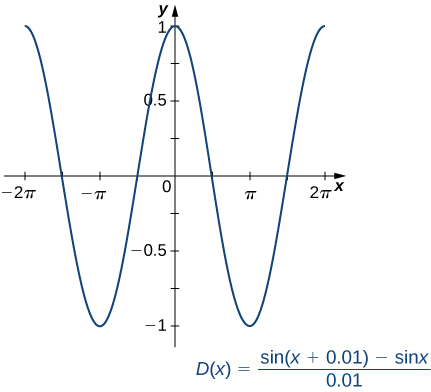

We see that by using \(h=0.01\),

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x)≈\dfrac{\sin (x+0.01)−\sin x}{0.01} \nonumber \]

By setting

\[D(x)=\dfrac{\sin (x+0.01)−\sin x}{0.01} \nonumber \]

and using a graphing utility, we can get a graph of an approximation to the derivative of \(\sin x\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Upon inspection, the graph of \(D(x)\) appears to be very close to the graph of the cosine function. Indeed, we will show that

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x)=\cos x. \nonumber \]

If we were to follow the same steps to approximate the derivative of the cosine function, we would find that

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cos x)=−\sin x. \nonumber \]

The derivative of the sine function is the cosine and the derivative of the cosine function is the negative sine.

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x)=\cos x \nonumber \]

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cos x)=−\sin x \nonumber \]

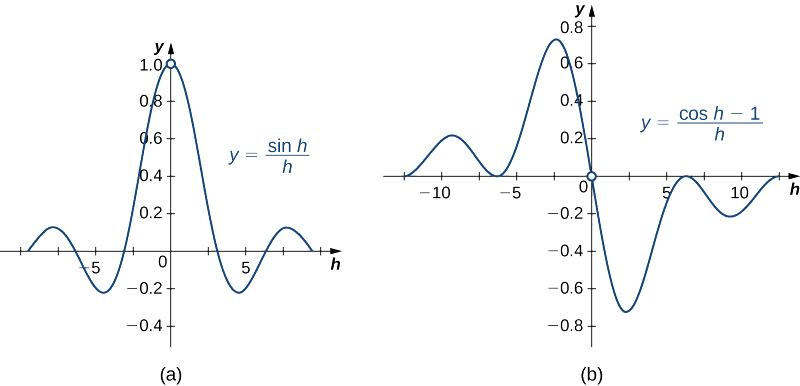

Because the proofs for \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x)=\cos x\) and \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cos x)=−\sin x\) use similar techniques, we provide only the proof for \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x)=\cos x\). Before beginning, recall two important trigonometric limits:

\(\displaystyle \lim_{h→0}\dfrac{\sin h}{h}=1\) and \(\displaystyle \lim_{h→0}\dfrac{\cos h−1}{h}=0\).

The graphs of \(y=\dfrac{\sin h}{h}\) and \(y=\dfrac{\cos h−1}{h}\) are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

We also recall the following trigonometric identity for the sine of the sum of two angles:

\[\sin (x+h)=\sin x\cos h+\cos x\sin h. \nonumber \]

Now that we have gathered all the necessary equations and identities, we proceed with the proof.

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x) &=\lim_{h→0}\dfrac{\sin(x+h)−\sin x}{h} & & \text{Apply the definition of the derivative.}\\[4pt]

&=\lim_{h→0}\dfrac{\sin x\cos h+\cos x\sin h−\sin x}{h} & & \text{Use trig identity for the sine of the sum of two angles.}\\[4pt]

&=\lim_{h→0}\left(\dfrac{\sin x\cos h−\sin x}{h}+\dfrac{\cos x\sin h}{h}\right) & & \text{Regroup.}\\[4pt]

&=\lim_{h→0}\left(\sin x\left(\dfrac{\cos h−1}{h}\right)+(\cos x)\left(\dfrac{\sin h}{h}\right)\right) & & \text{Factor out }\sin x\text{ and }\cos x \\[4pt]

&=(\sin x)\lim_{h→0}\left(\dfrac{\cos h−1}{h}\right)+(\cos x)\lim_{h→0}\left(\dfrac{\sin h}{h}\right) & & \text{Factor }\sin x\text{ and }\cos x \text{ out of limits.} \\[4pt]

&=(\sin x)(0)+(\cos x)(1) & & \text{Apply trig limit formulas.}\\[4pt]

&=\cos x & & \text{Simplify.} \end{align*} \nonumber \]

□

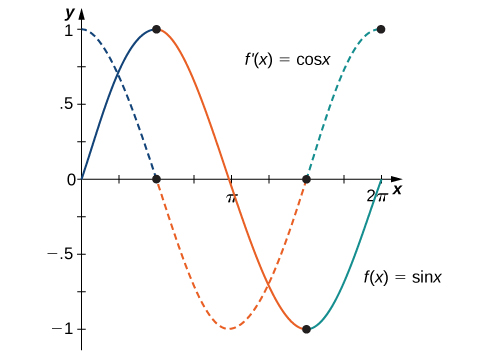

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows the relationship between the graph of \(f(x)=\sin x\) and its derivative \(f′(x)=\cos x\). Notice that at the points where \(f(x)=\sin x\) has a horizontal tangent, its derivative \(f′(x)=\cos x\) takes on the value zero. We also see that where f\((x)=\sin x\) is increasing, \(f′(x)=\cos x>0\) and where \(f(x)=\sin x\) is decreasing, \(f′(x)=\cos x<0.\)

Find the derivative of \(f(x)=5x^3\sin x\).

Solution

Using the product rule, we have

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &=\dfrac{d}{dx}(5x^3)⋅\sin x+\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x)⋅5x^3 \\[4pt] &=15x^2⋅\sin x+\cos x⋅5x^3. \end{align*}\]

After simplifying, we obtain

\[f′(x)=15x^2\sin x+5x^3\cos x. \nonumber \]

Find the derivative of \(f(x)=\sin x\cos x.\)

- Hint

-

Don’t forget to use the product rule.

- Answer

-

\[f′(x)=\cos^2x−\sin^2x \nonumber \]

Find the derivative of \(g(x)=\dfrac{\cos x}{4x^2}\).

Solution

By applying the quotient rule, we have

\[g′(x)=\dfrac{(−\sin x)4x^2−8x(\cos x)}{(4x^2)^2}. \nonumber \]

Simplifying, we obtain

\[g′(x)=\dfrac{−4x^2\sin x−8x\cos x}{16x^4}=\dfrac{−x\sin x−2\cos x}{4x^3}. \nonumber \]

Find the derivative of \(f(x)=\dfrac{x}{\cos x}\).

- Hint

-

Use the quotient rule.

- Answer

-

\(f'(x) = \dfrac{\cos x+x\sin x}{\cos^2x}\)

A particle moves along a coordinate axis in such a way that its position at time \(t\) is given by \(s(t)=2\sin t−t\) for \(0≤t≤2π.\) At what times is the particle at rest?

Solution

To determine when the particle is at rest, set \(s′(t)=v(t)=0.\) Begin by finding \(s′(t).\) We obtain

\[s′(t)=2 \cos t−1, \nonumber \]

so we must solve

\[2 \cos t−1=0\text{ for }0≤t≤2π. \nonumber \]

The solutions to this equation are \(t=\dfrac{π}{3}\) and \(t=\dfrac{5π}{3}\). Thus the particle is at rest at times \(t=\dfrac{π}{3}\) and \(t=\dfrac{5π}{3}\).

A particle moves along a coordinate axis. Its position at time \(t\) is given by \(s(t)=\sqrt{3}t+2\cos t\) for \(0≤t≤2π.\) At what times is the particle at rest?

- Hint

-

Use the previous example as a guide.

- Answer

-

\(t=\dfrac{π}{3},\quad t=\dfrac{2π}{3}\)

Derivatives of Other Trigonometric Functions

Since the remaining four trigonometric functions may be expressed as quotients involving sine, cosine, or both, we can use the quotient rule to find formulas for their derivatives.

Find the derivative of \(f(x)=\tan x.\)

Solution

Start by expressing \(\tan x \) as the quotient of \(\sin x\) and \(\cos x\):

\(f(x)=\tan x =\dfrac{\sin x}{\cos x}\).

Now apply the quotient rule to obtain

\(f′(x)=\dfrac{\cos x\cos x−(−\sin x)\sin x}{(\cos x)^2}\).

Simplifying, we obtain

\[f′(x)=\dfrac{\cos^2x+\sin^2 x}{\cos^2x}. \nonumber \]

Recognizing that \(\cos^2x+\sin^2x=1,\) by the Pythagorean theorem, we now have

\[f′(x)=\dfrac{1}{\cos^2x} \nonumber \]

Finally, use the identity \(\sec x=\dfrac{1}{\cos x}\) to obtain

\(f′(x)=\text{sec}^2 x\).

Find the derivative of \(f(x)=\cot x .\)

- Hint

-

Rewrite \(\cot x \) as \(\dfrac{\cos x}{\sin x}\) and use the quotient rule.

- Answer

-

\(f′(x)=−\csc^2 x\)

The derivatives of the remaining trigonometric functions may be obtained by using similar techniques. We provide these formulas in the following theorem.

The derivatives of the remaining trigonometric functions are as follows:

\[\begin{align} \dfrac{d}{dx}(\tan x )&=\sec^2x\\[4pt]

\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cot x )&=−\csc^2x\\[4pt]

\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sec x)&=\sec x \tan x\\[4pt]

\dfrac{d}{dx}(\csc x)&=−\csc x \cot x. \end{align} \nonumber \]

Find the equation of a line tangent to the graph of \(f(x)=\cot x \) at \(x=\frac{π}{4}\).

Solution

To find the equation of the tangent line, we need a point and a slope at that point. To find the point, compute

\(f\left(\frac{π}{4}\right)=\cot\frac{π}{4}=1\).

Thus the tangent line passes through the point \(\left(\frac{π}{4},1\right)\). Next, find the slope by finding the derivative of \(f(x)=\cot x \) and evaluating it at \(\frac{π}{4}\):

\(f′(x)=−\csc^2 x\) and \(f′\left(\frac{π}{4}\right)=−\csc^2\left(\frac{π}{4}\right)=−2\).

Using the point-slope equation of the line, we obtain

\(y−1=−2\left(x−\frac{π}{4}\right)\)

or equivalently,

\(y=−2x+1+\frac{π}{2}\).

Find the derivative of \(f(x)=\csc x+x\tan x .\)

Solution

To find this derivative, we must use both the sum rule and the product rule. Using the sum rule, we find

\(f′(x)=\dfrac{d}{dx}(\csc x)+\dfrac{d}{dx}(x\tan x )\).

In the first term, \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\csc x)=−\csc x\cot x ,\) and by applying the product rule to the second term we obtain

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(x\tan x )=(1)(\tan x )+(\sec^2 x)(x)\).

Therefore, we have

\(f′(x)=−\csc x\cot x +\tan x +x\sec^2 x\).

Find the derivative of \(f(x)=2\tan x −3\cot x .\)

- Hint

-

Use the rule for differentiating a constant multiple and the rule for differentiating a difference of two functions.

- Answer

-

\(f′(x)=2\sec^2 x+3\csc^2 x\)

Find the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(f(x)=\tan x \) at \(x=\dfrac{π}{6}\).

- Hint

-

Evaluate the derivative at \(x=\dfrac{π}{6}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{4}{3}\)

Higher-Order Derivatives

The higher-order derivatives of \(\sin x\) and \(\cos x\) follow a repeating pattern. By following the pattern, we can find any higher-order derivative of \(\sin x\) and \(\cos x.\)

Find the first four derivatives of \(y=\sin x.\)

Solution

Each step in the chain is straightforward:

\[\begin{align*} y&=\sin x \\[4pt]

\dfrac{dy}{dx}&=\cos x \\[4pt]

\dfrac{d^2y}{dx^2}&=−\sin x \\[4pt]

\dfrac{d^3y}{dx^3}&=−\cos x \\[4pt]

\dfrac{d^4y}{dx^4}&=\sin x \end{align*}\]

Analysis

Once we recognize the pattern of derivatives, we can find any higher-order derivative by determining the step in the pattern to which it corresponds. For example, every fourth derivative of \(\sin x\) equals \(\sin x\), so

\[\dfrac{d^4}{dx^4}(\sin x)=\dfrac{d^8}{dx^8}(\sin x)=\dfrac{d^{12}}{dx^{12}}(\sin x)=…=\dfrac{d^{4n}}{dx^{4n}}(\sin x)=\sin x \nonumber \]

\[\dfrac{d^5}{dx^5}(\sin x)=\dfrac{d^9}{dx^9}(\sin x)=\dfrac{d^{13}}{dx^{13}}(\sin x)=…=\dfrac{d^{4n+1}}{dx^{4n+1}}(\sin x)=\cos x. \nonumber \]

For \(y=\cos x\), find \(\dfrac{d^4y}{dx^4}\).

- Hint

-

See the previous example.

- Answer

-

\(\cos x\)

Find \(\dfrac{d^{74}}{dx^{74}}(\sin x)\).

Solution

We can see right away that for the 74th derivative of \(\sin x\), \(74=4(18)+2\), so

\[\dfrac{d^{74}}{dx^{74}}(\sin x)=\dfrac{d^{72+2}}{dx^{72+2}}(\sin x)=\dfrac{d^2}{dx^2}(\sin x)=−\sin x. \nonumber \]

For \(y=\sin x\), find \(\dfrac{d^{59}}{dx^{59}}(\sin x).\)

- Hint

-

\(\dfrac{d^{59}}{dx^{59}}(\sin x)=\dfrac{d^{4⋅14+3}}{dx^{4⋅14+3}}(\sin x)\)

- Answer

-

\(−\cos x\)

A particle moves along a coordinate axis in such a way that its position at time \(t\) is given by \(s(t)=2−\sin t\). Find \(v(π/4)\) and \(a(π/4)\). Compare these values and decide whether the particle is speeding up or slowing down.

Solution

First find \(v(t)=s′(t)\)

\[v(t)=s′(t)=−\cos t . \nonumber \]

Thus,

\(v\left(\frac{π}{4}\right)=−\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}=-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\).

Next, find \(a(t)=v′(t)\). Thus, \(a(t)=v′(t)=\sin t\) and we have

\(a\left(\frac{π}{4}\right)=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\).

Since \(v\left(\frac{π}{4}\right)=−\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}<0\) and \(a\left(\frac{π}{4}\right)=\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}>0\), we see that velocity and acceleration are acting in opposite directions; that is, the object is being accelerated in the direction opposite to the direction in which it is traveling. Consequently, the particle is slowing down.

A block attached to a spring is moving vertically. Its position at time t is given by \(s(t)=2\sin t\). Find \(v\left(\frac{5π}{6}\right)\) and \(a\left(\frac{5π}{6}\right)\). Compare these values and decide whether the block is speeding up or slowing down.

- Hint

-

Use Example \(\PageIndex{9}\) as a guide.

- Answer

-

\(v\left(\frac{5π}{6}\right)=−\sqrt{3}<0\) and \(a\left(\frac{5π}{6}\right)=−1<0\). The block is speeding up.

Key Concepts

- We can find the derivatives of \(\sin x\) and \(\cos x\) by using the definition of derivative and the limit formulas found earlier. The results are

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}\big(\sin x\big)=\cos x\quad\text{and}\quad\dfrac{d}{dx}\big(\cos x\big)=−\sin x\).

- With these two formulas, we can determine the derivatives of all six basic trigonometric functions.

Key Equations

- Derivative of sine function

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x)=\cos x\)

- Derivative of cosine function

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cos x)=−\sin x\)

- Derivative of tangent function

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\tan x )=\sec^2x\)

- Derivative of cotangent function

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cot x )=−\csc^2x\)

- Derivative of secant function

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sec x)=\sec x\tan x \)

- Derivative of cosecant function

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\csc x)=−\csc x\cot x \)