6.7: Integrals, Exponential Functions, and Logarithms

- Page ID

- 2525

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Write the definition of the natural logarithm as an integral.

- Recognize the derivative of the natural logarithm.

- Integrate functions involving the natural logarithmic function.

- Define the number \(e\) through an integral.

- Recognize the derivative and integral of the exponential function.

- Prove properties of logarithms and exponential functions using integrals.

- Express general logarithmic and exponential functions in terms of natural logarithms and exponentials.

We already examined exponential functions and logarithms in earlier chapters. However, we glossed over some key details in the previous discussions. For example, we did not study how to treat exponential functions with exponents that are irrational. The definition of the number e is another area where the previous development was somewhat incomplete. We now have the tools to deal with these concepts in a more mathematically rigorous way, and we do so in this section.

For purposes of this section, assume we have not yet defined the natural logarithm, the number \(e\), or any of the integration and differentiation formulas associated with these functions. By the end of the section, we will have studied these concepts in a mathematically rigorous way (and we will see they are consistent with the concepts we learned earlier). We begin the section by defining the natural logarithm in terms of an integral. This definition forms the foundation for the section. From this definition, we derive differentiation formulas, define the number \(e\), and expand these concepts to logarithms and exponential functions of any base.

The Natural Logarithm as an Integral

Recall the power rule for integrals:

\[ ∫ x^n \,dx = \dfrac{x^{n+1}}{n+1} + C , \quad n≠−1. \nonumber \]

Clearly, this does not work when \(n=−1,\) as it would force us to divide by zero. So, what do we do with \(\displaystyle ∫\dfrac{1}{x}\,dx\)? Recall from the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus that \(\displaystyle ∫^x_1\dfrac{1}{t}dt\) is an antiderivative of \(\dfrac{1}{x}.\) Therefore, we can make the following definition.

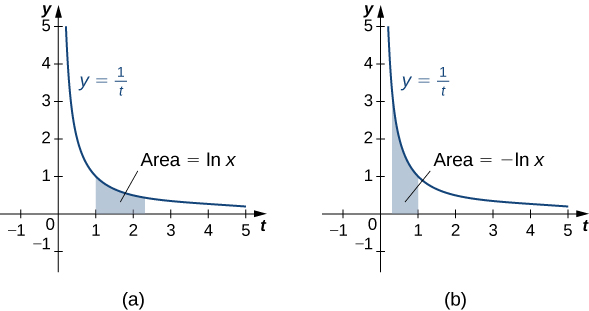

For \(x>0\), define the natural logarithm function by

\[\ln x=∫^x_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt. \nonumber \]

For \(x>1\), this is just the area under the curve \(y=\dfrac{1}{t}\) from \(1\) to \(x\). For \(x<1\), we have

\[ ∫^x_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt=−∫^1_x\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt, \nonumber \]

so in this case it is the negative of the area under the curve from \(x\) to \(1\) (see the following figure).

Notice that \(\ln 1=0\). Furthermore, the function \(y=\dfrac{1}{t}>0\) for \(x>0\). Therefore, by the properties of integrals, it is clear that \(\ln x\) is increasing for \(x>0\).

Properties of the Natural Logarithm

Because of the way we defined the natural logarithm, the following differentiation formula falls out immediately as a result of to the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

For \(x>0\), the derivative of the natural logarithm is given by

\[ \dfrac{d}{dx}\Big( \ln x \Big) = \dfrac{1}{x}. \nonumber \]

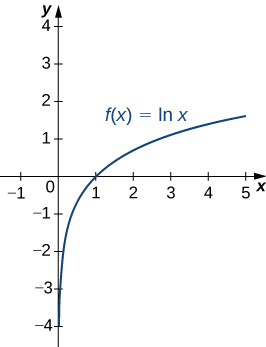

The function \(\ln x\) is differentiable; therefore, it is continuous.

A graph of \(\ln x\) is shown in Figure. Notice that it is continuous throughout its domain of \((0,∞)\).

Calculate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\ln (5x^3−2)\Big)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big((\ln (3x))^2\Big)\)

Solution

We need to apply the chain rule in both cases.

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\ln (5x^3−2)\Big)=\dfrac{15x^2}{5x^3−2}\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big((\ln (3x))^2\Big)=\dfrac{2(\ln (3x))⋅3}{3x}=\dfrac{2(\ln (3x))}{x}\)

Calculate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\ln (2x^2+x)\Big)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big((\ln (x^3))^2\Big)\)

- Hint

-

Apply the differentiation formula just provided and use the chain rule as necessary.

- Answer

-

a. \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\ln (2x^2+x)\Big)=\dfrac{4x+1}{2x^2+x}\)

b. \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big((\ln (x^3))^2\Big)=\dfrac{6\ln (x^3)}{x}\)

Note that if we use the absolute value function and create a new function \(\ln |x|\), we can extend the domain of the natural logarithm to include \(x<0\). Then \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big( \ln x \Big)=\dfrac{1}{x}\). This gives rise to the familiar integration formula.

The natural logarithm is the antiderivative of the function \(f(u)=\dfrac{1}{u}\):

\[∫\dfrac{1}{u}\,du=\ln |u|+C. \nonumber \]

Calculate the integral \(\displaystyle ∫\dfrac{x}{x^2+4}\,dx.\)

Solution

Using \(u\)-substitution, let \(u=x^2+4\). Then \(du=2x\,dx\) and we have

\(\displaystyle ∫\dfrac{x}{x^2+4}\,dx=\dfrac{1}{2}∫\dfrac{1}{u}\,du=\dfrac{1}{2}\ln |u|+C=\dfrac{1}{2}\ln |x^2+4|+C=\dfrac{1}{2}\ln (x^2+4)+C.\)

Calculate the integral \(\displaystyle ∫\dfrac{x^2}{x^3+6}\,dx.\)

- Hint

-

Apply the integration formula provided earlier and use u-substitution as necessary.

- Answer

-

\(\displaystyle ∫\dfrac{x^2}{x^3+6}\,dx=\dfrac{1}{3}\ln ∣x^3+6∣+C\)

Although we have called our function a “logarithm,” we have not actually proved that any of the properties of logarithms hold for this function. We do so here.

If \(a,\, b>0\) and \(r\) is a rational number, then

- \(\ln 1=0\)

- \(\ln (ab)=\ln a+\ln b\)

- \(\ln \left(\dfrac{a}{b}\right)=\ln a−\ln b\)

- \(\ln \left(a^r\right)=r\ln a\)

i. By definition, \(\displaystyle \ln 1=∫^1_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt=0.\)

ii. We have

\(\displaystyle \ln (ab)=∫^{ab}_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt=∫^a_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt+∫^{ab}_a\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt.\)

Use \(u-substitution\) on the last integral in this expression. Let \(u=t/a\). Then \(du=(1/a)dt.\) Furthermore, when \(t=a,\, u=1\), and when \(t=ab,\, u=b.\) So we get

\(\displaystyle \ln (ab)=∫^a_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt+∫^{ab}_a\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt=∫^a_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt+∫^{ab}_1\dfrac{a}{t}⋅\dfrac{1}{a}\,dt=∫^a_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt+∫^b_1\dfrac{1}{u}\,du=\ln a+\ln b.\)

iii. Note that

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\ln (x^r)\Big)=\dfrac{rx^{r−1}}{x^r}=\dfrac{r}{x}\).

Furthermore,

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big((r\ln x)\Big)=\dfrac{r}{x}.\)

Since the derivatives of these two functions are the same, by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, they must differ by a constant. So we have

\(\ln (x^r)=r\ln x+C\)

for some constant \(C\). Taking \(x=1\), we get

\(\ln (1^r)=r\ln (1)+C\)

\(0=r(0)+C\)

\(C=0.\)

Thus \(\ln (x^r)=r\ln x\) and the proof is complete. Note that we can extend this property to irrational values of \(r\) later in this section.

Part iii. follows from parts ii. and iv. and the proof is left to you.

□

Use properties of logarithms to simplify the following expression into a single logarithm:

\( \ln 9−2 \ln 3+\ln \left(\tfrac{1}{3}\right).\)

Solution

We have

\( \ln 9−2 \ln 3+\ln \left(\tfrac{1}{3}\right)=\ln (3^2)−2 \ln 3+\ln (3^{−1})=2\ln 3−2\ln 3−\ln 3=−\ln 3.\)

Use properties of logarithms to simplify the following expression into a single logarithm:

\( \ln 8−\ln 2−\ln \left(\tfrac{1}{4}\right)\)

- Hint

-

Apply the properties of logarithms.

- Answer

-

\(4\ln 2\)

Defining the Number e

Now that we have the natural logarithm defined, we can use that function to define the number \(e\).

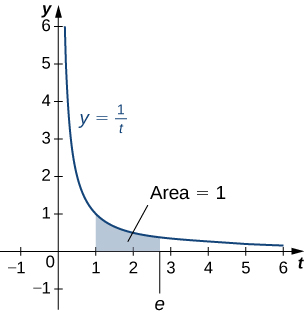

The number \(e\) is defined to be the real number such that

\[\ln e=1\nonumber \]

To put it another way, the area under the curve \(y=1/t\) between \(t=1\) and \(t=e\) is \(1\) (Figure). The proof that such a number exists and is unique is left to you. (Hint: Use the Intermediate Value Theorem to prove existence and the fact that \(\ln x\) is increasing to prove uniqueness.)

The number \(e\) can be shown to be irrational, although we won’t do so here (see the Student Project in Taylor and Maclaurin Series). Its approximate value is given by

\( e≈2.71828182846.\)

The Exponential Function

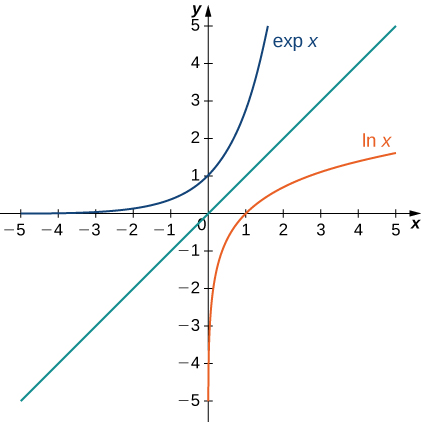

We now turn our attention to the function \(e^x\). Note that the natural logarithm is one-to-one and therefore has an inverse function. For now, we denote this inverse function by \(\exp x\). Then,

\[ \exp(\ln x)=x \nonumber \]

for \(x>0\) and

\[ \ln (\exp x)=x \nonumber \]

for all \(x\).

The following figure shows the graphs of \(\exp x\) and \(\ln x\).

We hypothesize that \(\exp x=e^x\). For rational values of \(x\), this is easy to show. If \(x\) is rational, then we have \(\ln (e^x)=x\ln e=x\). Thus, when \(x\) is rational, \(e^x=\exp x\). For irrational values of \(x\), we simply define \(e^x\) as the inverse function of \(\ln x\).

For any real number \(x\), define \(y=e^x\) to be the number for which

\[\ln y=\ln (e^x)=x. \nonumber \]

Then we have \(e^x=\exp x\) for all \(x\), and thus

\(e^{\ln x}=x\) for \(x>0\) and \(\ln (e^x)=x\)

for all \(x\).

Properties of the Exponential Function

Since the exponential function was defined in terms of an inverse function, and not in terms of a power of \(e\) we must verify that the usual laws of exponents hold for the function \(e^x\).

If \(p\) and \(q\) are any real numbers and \(r\) is a rational number, then

- \(e^pe^q=e^{p+q}\)

- \(\dfrac{e^p}{e^q}=e^{p−q}\)

- \((e^p)^r=e^{pr}\)

Note that if \(p\) and \(q\) are rational, the properties hold. However, if \(p\) or \(q\) are irrational, we must apply the inverse function definition of \(e^x\) and verify the properties. Only the first property is verified here; the other two are left to you. We have

\[ \ln (e^pe^q)=\ln (e^p)+\ln (e^q)=p+q=\ln (e^{p+q}).\nonumber \]

Since \(\ln x\) is one-to-one, then

\[ e^pe^q=e^{p+q}.\nonumber \]

□

As with part iv. of the logarithm properties, we can extend property iii. to irrational values of \(r\), and we do so by the end of the section.

We also want to verify the differentiation formula for the function \(y=e^x\). To do this, we need to use implicit differentiation. Let \(y=e^x\). Then

\[ \begin{align*} \ln y &=x \\[5pt] \dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\ln y\Big) &=\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(x\Big) \\[5pt] \dfrac{1}{y}\dfrac{dy}{dx} &=1 \\[5pt] \dfrac{dy}{dx} &=y. \end{align*}\]

Thus, we see

\[ \dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(e^x\Big)=e^x \nonumber \]

as desired, which leads immediately to the integration formula

\[ ∫e^x \,dx=e^x+C. \nonumber \]

We apply these formulas in the following examples.

Evaluate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(e^{3t}e^{t^2}\Big)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(e^{3x^2}\Big)\)

Solution

We apply the chain rule as necessary.

- \(\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(e^{3t}e^{t^2}\Big)=\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(e^{3t+t^2}\Big)=e^{3t+t^2}(3+2t)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(e^{3x^2}\Big)=e^{3x^2}6x\)

Evaluate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\dfrac{e^{x^2}}{e^{5x}}\Big)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big((e^{2t})^3\Big)\)

- Hint

-

Use the properties of exponential functions and the chain rule as necessary.

- Answer

-

a. \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\dfrac{e^{x^2}}{e^{5x}}\Big)=e^{x^{2−5x}}(2x−5)\)

b. \(\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big((e^{2t})^3\Big)=6e^{6t}\)

Evaluate the following integral: \(\displaystyle ∫2xe^{−x^2}\,dx.\)

Solution

Using \(u\)-substitution, let \(u=−x^2\). Then \(du=−2x\,dx,\) and we have

\(\displaystyle ∫2xe^{−x^2}\,dx=−∫e^u\,du=−e^u+C=−e^{−x^2}+C.\)

Evaluate the following integral: \(\displaystyle ∫\dfrac{4}{e^{3x}}\,dx.\)

- Hint

-

Use the properties of exponential functions and \(u-substitution\) as necessary.

- Answer

-

\(\displaystyle ∫\dfrac{4}{e^{3x}}\,dx=−\dfrac{4}{3}e^{−3x}+C\)

General Logarithmic and Exponential Functions

We close this section by looking at exponential functions and logarithms with bases other than \(e\). Exponential functions are functions of the form \(f(x)=a^x\). Note that unless \(a=e\), we still do not have a mathematically rigorous definition of these functions for irrational exponents. Let’s rectify that here by defining the function \(f(x)=a^x\) in terms of the exponential function \(e^x\). We then examine logarithms with bases other than e as inverse functions of exponential functions.

For any \(a>0,\) and for any real number \(x\), define \(y=a^x\) as follows:

\[y=a^x=e^{x \ln a}. \nonumber \]

Now \(a^x\) is defined rigorously for all values of \(x\). This definition also allows us to generalize property iv. of logarithms and property iii. of exponential functions to apply to both rational and irrational values of \(r\). It is straightforward to show that properties of exponents hold for general exponential functions defined in this way.

Let’s now apply this definition to calculate a differentiation formula for \(a^x\). We have

\(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(a^x\Big)=\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(e^{x\ln a}\Big)=e^{x\ln a}\ln a=a^x\ln a.\)

The corresponding integration formula follows immediately.

Let \(a>0.\) Then,

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(a^x\Big)=a^x \ln a \nonumber \]

and

\[∫a^x\,dx=\dfrac{1}{\ln a}a^x+C. \nonumber \]

If \(a≠1\), then the function \(a^x\) is one-to-one and has a well-defined inverse. Its inverse is denoted by \(\log_a x\). Then,

\( y=\log_a x\) if and only if \(x=a^y.\)

Note that general logarithm functions can be written in terms of the natural logarithm. Let \(y=\log_a x.\) Then, \(x=a^y\). Taking the natural logarithm of both sides of this second equation, we get

\[\begin{align*} \ln x &=\ln (a^y)\\[5pt]

\ln x&=y\ln a\\[5pt]

y&=\dfrac{\ln x}{\ln a}\\[5pt]

\log_a x&=\dfrac{\ln x}{\ln a}.\end{align*}\]

Thus, we see that all logarithmic functions are constant multiples of one another. Next, we use this formula to find a differentiation formula for a logarithm with base \(a\). Again, let \(y=\log_a x\). Then,

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dy}{dx}&=\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\log_a x\Big)\\[5pt]

&=\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{\ln x}{\ln a}\right)\\[5pt]

&=(\dfrac{1}{\ln a})\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\ln x\Big)\\[5pt]

&=\dfrac{1}{\ln a}⋅\dfrac{1}{x}=\dfrac{1}{x\ln a} \end{align*}\]

Let \(a>0.\) Then,

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\log_a x\Big)=\dfrac{1}{x\ln a}. \nonumber \]

Evaluate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(4^t⋅2^{t^2}\Big)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\log_8(7x^2+4)\Big)\)

Solution: We need to apply the chain rule as necessary.

- \(\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(4^t⋅2^{t^2}\Big)=\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(2^{2t}⋅2^{t^2}\Big)=\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(2^{2t+t^2}\Big)=2^{2t+t^2}\ln (2)(2+2t)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\log_8(7x^2+4)\Big)=\dfrac{1}{(7x^2+4)(\ln 8)}(14x)\)

Evaluate the following derivatives:

- \(\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(4^{t^4}\Big)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\log_3(\sqrt{x^2+1})\Big)\)

- Hint

-

Use the formulas and apply the chain rule as necessary.

- Answer

-

a. \(\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(4^{t^4}\Big)=4^{t^4}(\ln 4)(4t^3)\)

b. \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\log_3(\sqrt{x^2+1})\Big)=\dfrac{x}{(\ln 3)(x^2+1)}\)

Evaluate the following integral: \(\displaystyle ∫\dfrac{3}{2^{3x}}\,dx.\)

Solution

Use \(u-substitution\) and let \(u=−3x\). Then \(du=−3\,dx\) and we have

\[ ∫\dfrac{3}{2^{3x}}\,dx=∫3⋅2^{−3x}\,dx=−∫2^u\,du=−\dfrac{1}{\ln 2}2^u+C=−\dfrac{1}{\ln 2}2^{−3x}+C.\nonumber \]

Evaluate the following integral: \(\displaystyle ∫x^2 2^{x^3}\,dx.\)

- Hint

-

Use the properties of exponential functions and u-substitution

- Answer

-

\(\displaystyle ∫x^2 2^{x^3}\,dx=\dfrac{1}{3\ln 2}2^{x^3}+C\)

Key Concepts

- The earlier treatment of logarithms and exponential functions did not define the functions precisely and formally. This section develops the concepts in a mathematically rigorous way.

- The cornerstone of the development is the definition of the natural logarithm in terms of an integral.

- The function \(e^x\) is then defined as the inverse of the natural logarithm. General exponential functions are defined in terms of \(e^x\), and the corresponding inverse functions are general logarithms.

- Familiar properties of logarithms and exponents still hold in this more rigorous context.

Key Equations

- Natural logarithm function

- \(\displaystyle \ln x=∫^x_1\dfrac{1}{t}\,dt\)

- Exponential function \(y=e^x\)

- \(\ln y=\ln (e^x)=x\)