11.5: Conic Sections

- Page ID

- 2584

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Identify the equation of a parabola in standard form with given focus and directrix.

- Identify the equation of an ellipse in standard form with given foci.

- Identify the equation of a hyperbola in standard form with given foci.

- Recognize a parabola, ellipse, or hyperbola from its eccentricity value.

- Write the polar equation of a conic section with eccentricity \(e\).

- Identify when a general equation of degree two is a parabola, ellipse, or hyperbola.

Conic sections have been studied since the time of the ancient Greeks, and were considered to be an important mathematical concept. As early as 320 BCE, such Greek mathematicians as Menaechmus, Appollonius, and Archimedes were fascinated by these curves. Appollonius wrote an entire eight-volume treatise on conic sections in which he was, for example, able to derive a specific method for identifying a conic section through the use of geometry. Since then, important applications of conic sections have arisen (for example, in astronomy), and the properties of conic sections are used in radio telescopes, satellite dish receivers, and even architecture. In this section we discuss the three basic conic sections, some of their properties, and their equations.

Conic sections get their name because they can be generated by intersecting a plane with a cone. A cone has two identically shaped parts called nappes. One nappe is what most people mean by “cone,” having the shape of a party hat. A right circular cone can be generated by revolving a line passing through the origin around the y-axis as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Conic sections are generated by the intersection of a plane with a cone (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). If the plane is parallel to the axis of revolution (the y-axis), then the conic section is a hyperbola. If the plane is parallel to the generating line, the conic section is a parabola. If the plane is perpendicular to the axis of revolution, the conic section is a circle. If the plane intersects one nappe at an angle to the axis (other than 90°), then the conic section is an ellipse.

Parabolas

A parabola is generated when a plane intersects a cone parallel to the generating line. In this case, the plane intersects only one of the nappes. A parabola can also be defined in terms of distances.

A parabola is the set of all points whose distance from a fixed point, called the focus, is equal to the distance from a fixed line, called the directrix. The point halfway between the focus and the directrix is called the vertex of the parabola.

A graph of a typical parabola appears in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). Using this diagram in conjunction with the distance formula, we can derive an equation for a parabola. Recall the distance formula: Given point \(P\) with coordinates \((x_1,y_1)\) and point \(Q\) with coordinates \((x_2,y_2),\) the distance between them is given by the formula

\[d(P,Q)=\sqrt{(x_2−x_1)^2+(y_2−y_1)^2}. \nonumber \]

Then from the definition of a parabola and Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), we get

\[d(F,P)=d(P,Q) \nonumber \]

\[\sqrt{(0−x)^2+(p−y)^2}=\sqrt{(x−x)^2+(−p−y)^2}. \nonumber \]

Squaring both sides and simplifying yields

\[ \begin{align} x^2+(p−y)^2 = 0^2+(−p−y)^2 \\ x^2+p^2−2py+y^2 = p^2+2py+y^2 \\ x^2−2py =2py \\ x^2 =4py. \end{align} \nonumber \]

Now suppose we want to relocate the vertex. We use the variables \((h,k)\) to denote the coordinates of the vertex. Then if the focus is directly above the vertex, it has coordinates \((h,\, k+p)\) and the directrix has the equation \(y=k−p\). Going through the same derivation yields the formula \((x−h)^2=4p(y−k)\). Solving this equation for \(y\) leads to the following theorem.

Given a parabola opening upward with vertex located at \((h,k)\) and focus located at \((h,k+p)\), where \(p\) is a constant, the equation for the parabola is given by

\[y=\dfrac{1}{4p}(x−h)^2+k. \label{paraeqstandform} \]

This is the standard form of a parabola.

We can also study the cases when the parabola opens down or to the left or the right. The equation for each of these cases can also be written in standard form as shown in the following graphs.

In addition, the equation of a parabola can be written in the general form, though in this form the values of \(h\), \(k\), and \(p\) are not immediately recognizable. The general form of a parabola is written as

\[ax^2+bx+cy+d=0 \label{para1} \]

or

\[ay^2+bx+cy+d=0.\label{para2} \]

Equation \ref{para1} represents a parabola that opens either up or down. Equation \ref{para2} represents a parabola that opens either to the left or to the right. To put the equation into standard form, use the method of completing the square.

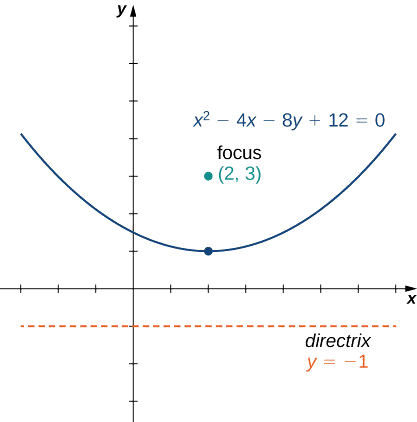

Put the equation

\[x^2−4x−8y+12=0 \nonumber \]

into standard form and graph the resulting parabola.

Solution

Since \(y\) is not squared in this equation, we know that the parabola opens either upward or downward. Therefore we need to solve this equation for \(y\), which will put the equation into standard form. To do that, first add \(8y\) to both sides of the equation:

\[8y=x^2−4x+12. \nonumber \]

The next step is to complete the square on the right-hand side. Start by grouping the first two terms on the right-hand side using parentheses:

\[8y=(x^2−4x)+12. \nonumber \]

Next determine the constant that, when added inside the parentheses, makes the quantity inside the parentheses a perfect square trinomial. To do this, take half the coefficient of \(x\) and square it. This gives \(\left(\dfrac{−4}{2}\right)^2=4.\) Add \(4\) inside the parentheses and subtract \(4\) outside the parentheses, so the value of the equation is not changed:

\[8y=(x^2−4x+4)+12−4. \nonumber \]

Now combine like terms and factor the quantity inside the parentheses:

\[8y=(x−2)^2+8. \nonumber \]

Finally, divide by \(8\):

\[y=\dfrac{1}{8}(x−2)^2+1. \nonumber \]

This equation is now in standard form. Comparing this to Equation \ref{paraeqstandform} gives \(h=2, \, k=1\), and \(p=2\). The parabola opens up, with vertex at \((2,1)\), focus at \((2,3)\), and directrix \(y=−1\). The graph of this parabola appears as follows.

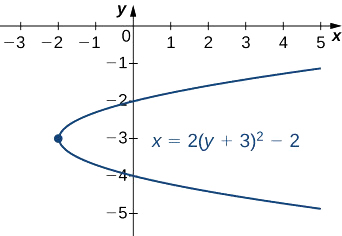

Put the equation \(2y^2−x+12y+16=0\) into standard form and graph the resulting parabola.

- Hint

-

Solve for \(x\). Check which direction the parabola opens.

- Answer

-

\[x=2(y+3)^2−2 \nonumber \]

The axis of symmetry of a vertical (opening up or down) parabola is a vertical line passing through the vertex. The parabola has an interesting reflective property. Suppose we have a satellite dish with a parabolic cross section. If a beam of electromagnetic waves, such as light or radio waves, comes into the dish in a straight line from a satellite (parallel to the axis of symmetry), then the waves reflect off the dish and collect at the focus of the parabola as shown.

Consider a parabolic dish designed to collect signals from a satellite in space. The dish is aimed directly at the satellite, and a receiver is located at the focus of the parabola. Radio waves coming in from the satellite are reflected off the surface of the parabola to the receiver, which collects and decodes the digital signals. This allows a small receiver to gather signals from a wide angle of sky. Flashlights and headlights in a car work on the same principle, but in reverse: the source of the light (that is, the light bulb) is located at the focus and the reflecting surface on the parabolic mirror focuses the beam straight ahead. This allows a small light bulb to illuminate a wide angle of space in front of the flashlight or car.

Ellipses

An ellipse can also be defined in terms of distances. In the case of an ellipse, there are two foci (plural of focus), and two directrices (plural of directrix). We look at the directrices in more detail later in this section.

An ellipse is the set of all points for which the sum of their distances from two fixed points (the foci) is constant.

A graph of a typical ellipse is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). In this figure the foci are labeled as \(F\) and \(F′\). Both are the same fixed distance from the origin, and this distance is represented by the variable \(c\). Therefore the coordinates of \(F\) are \((c,0)\) and the coordinates of \(F′\) are \((−c,0).\) The points \(P\) and \(P′\) are located at the ends of the major axis of the ellipse, and have coordinates \((a,0)\) and \((−a,0)\), respectively. The major axis is always the longest distance across the ellipse, and can be horizontal or vertical. Thus, the length of the major axis in this ellipse is \(2a\). Furthermore, \(P\) and \(P′\) are called the vertices of the ellipse. The points \(Q\) and \(Q′\) are located at the ends of the minor axis of the ellipse, and have coordinates \((0,b)\) and \((0,−b),\) respectively. The minor axis is the shortest distance across the ellipse. The minor axis is perpendicular to the major axis.

According to the definition of the ellipse, we can choose any point on the ellipse and the sum of the distances from this point to the two foci is constant. Suppose we choose the point \(P\). Since the coordinates of point \(P\) are \((a,0),\) the sum of the distances is

\[d(P,F)+d(P,F′)=(a−c)+(a+c)=2a. \nonumber \]

Therefore the sum of the distances from an arbitrary point A with coordinates \((x,y)\) is also equal to \(2a\). Using the distance formula, we get

\[d(A,F)+d(A,F′)=2a. \nonumber \]

\[\sqrt{(x−c)^2+y^2}+\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}=2a \nonumber \]

Subtract the second radical from both sides and square both sides:

\[\sqrt{(x−c)^2+y^2}=2a−\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2} \nonumber \]

\[(x−c)^2+y^2=4a^2−4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+(x+c)^2+y^2 \nonumber \]

\[x^2−2cx+c^2+y^2=4a^2−4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+x^2+2cx+c^2+y^2 \nonumber \]

\[−2cx=4a^2−4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+2cx. \nonumber \]

Now isolate the radical on the right-hand side and square again:

\[−2cx=4a^2−4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+2cx \nonumber \]

\[4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}=4a^2+4cx \nonumber \]

\[\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}=a+\dfrac{cx}{a} \nonumber \]

\[(x+c)^2+y^2=a^2+2cx+\dfrac{c^2x^2}{a^2} \nonumber \]

\[x^2+2cx+c^2+y^2=a^2+2cx+\dfrac{c^2x^2}{a^2} \nonumber \]

\[x^2+c^2+y^2=a^2+\dfrac{c^2x^2}{a^2}. \nonumber \]

Isolate the variables on the left-hand side of the equation and the constants on the right-hand side:

\[x^2−\dfrac{c^2x^2}{a^2}+y^2=a^2−c^2 \nonumber \]

\[\dfrac{(a^2−c^2)x^2}{a^2}+y^2=a^2−c^2. \nonumber \]

Divide both sides by \(a^2−c^2\). This gives the equation

\[\dfrac{x^2}{a^2}+\dfrac{y^2}{a^2−c^2}=1. \nonumber \]

If we refer back to Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), then the length of each of the two green line segments is equal to \(a\). This is true because the sum of the distances from the point \(Q\) to the foci \(F\) and \(F′\) is equal to \(2a\), and the lengths of these two line segments are equal. This line segment forms a right triangle with hypotenuse length \(a\) and leg lengths \(b\) and \(c\). From the Pythagorean theorem, \(b^2+c^2=a^2\) and \(b^2=a^2−c^2\). Therefore the equation of the ellipse becomes

\[\dfrac{x^2}{a^2}+\dfrac{y^2}{b^2}=1. \nonumber \]

Finally, if the center of the ellipse is moved from the origin to a point \((h,k)\), we have the following standard form of an ellipse.

Consider the ellipse with center \((h,k)\), a horizontal major axis with length \(2a\), and a vertical minor axis with length \(2b\). Then the equation of this ellipse in standard form is

\[\dfrac{(x−h)^2}{a^2}+\dfrac{(y−k)^2}{b^2}=1 \label{HorEllipse} \]

and the foci are located at \((h±c,k)\), where \(c^2=a^2−b^2\). The equations of the directrices are \(x=h±\dfrac{a^2}{c}\).

If the major axis is vertical, then the equation of the ellipse becomes

\[\dfrac{(x−h)^2}{b^2}+\dfrac{(y−k)^2}{a^2}=1 \label{VertEllipse} \]

and the foci are located at \((h,k±c)\), where \(c^2=a^2−b^2\). The equations of the directrices in this case are \(y=k±\dfrac{a^2}{c}\).

If the major axis is horizontal, then the ellipse is called horizontal, and if the major axis is vertical, then the ellipse is called vertical. The equation of an ellipse is in general form if it is in the form

\[Ax^2+By^2+Cx+Dy+E=0, \nonumber \]

where A and B are either both positive or both negative. To convert the equation from general to standard form, use the method of completing the square.

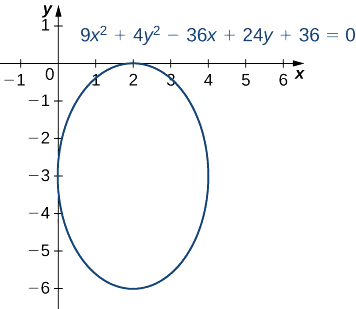

Put the equation

\[9x^2+4y^2−36x+24y+36=0 \nonumber \]

into standard form and graph the resulting ellipse.

Solution

First subtract 36 from both sides of the equation:

\[9x^2+4y^2−36x+24y=−36. \nonumber \]

Next group the \(x\) terms together and the \(y\) terms together, and factor out the common factor:

\[(9x^2−36x)+(4y^2+24y)=−36 \nonumber \]

\[9(x^2−4x)+4(y^2+6y)=−36. \nonumber \]

We need to determine the constant that, when added inside each set of parentheses, results in a perfect square. In the first set of parentheses, take half the coefficient of \(x\) and square it. This gives \(\left(\dfrac{−4}{2}\right)^2=4.\) In the second set of parentheses, take half the coefficient of \(y\) and square it. This gives \(\left(\dfrac{6}{2}\right)^2=9.\) Add these inside each pair of parentheses. Since the first set of parentheses has a 9 in front, we are actually adding 36 to the left-hand side. Similarly, we are adding 36 to the second set as well. Therefore the equation becomes

\[9(x^2−4x+4)+4(y^2+6y+9)=−36+36+36 \nonumber \]

\[9(x^2−4x+4)+4(y^2+6y+9)=36. \nonumber \]

Now factor both sets of parentheses and divide by 36:

\[9(x−2)^2+4(y+3)^2=36 \nonumber \]

\[\dfrac{9(x−2)^2}{36}+\dfrac{4(y+3)^2}{36}=1 \nonumber \]

\[\dfrac{(x−2)^2}{4}+\dfrac{(y+3)^2}{9}=1. \nonumber \]

The equation is now in standard form. Comparing this to Equation \ref{VertEllipse} gives \(h=2, k=−3, a=3,\) and \(b=2\). This is a vertical ellipse with center at \((2,−3)\), major axis 6, and minor axis 4. The graph of this ellipse appears as follows.

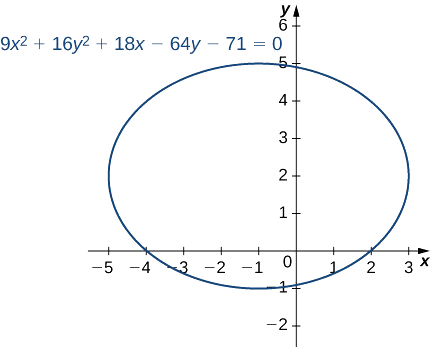

Put the equation

\[9x^2+16y^2+18x−64y−71=0 \nonumber \]

into standard form and graph the resulting ellipse.

- Hint

-

Move the constant over and complete the square.

- Answer

-

\[\dfrac{(x+1)^2}{16}+\dfrac{(y−2)^2}{9}=1 \nonumber \]

According to Kepler’s first law of planetary motion, the orbit of a planet around the Sun is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the foci as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8A}\). Because Earth’s orbit is an ellipse, the distance from the Sun varies throughout the year. A commonly held misconception is that Earth is closer to the Sun in the summer. In fact, in summer for the northern hemisphere, Earth is farther from the Sun than during winter. The difference in season is caused by the tilt of Earth’s axis in the orbital plane. Comets that orbit the Sun, such as Halley’s Comet, also have elliptical orbits, as do moons orbiting the planets and satellites orbiting Earth.

Ellipses also have interesting reflective properties: A light ray emanating from one focus passes through the other focus after mirror reflection in the ellipse. The same thing occurs with a sound wave as well. The National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC, is a famous room in an elliptical shape as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8B}\). This hall served as the meeting place for the U.S. House of Representatives for almost fifty years. The location of the two foci of this semi-elliptical room are clearly identified by marks on the floor, and even if the room is full of visitors, when two people stand on these spots and speak to each other, they can hear each other much more clearly than they can hear someone standing close by. Legend has it that John Quincy Adams had his desk located on one of the foci and was able to eavesdrop on everyone else in the House without ever needing to stand. Although this makes a good story, it is unlikely to be true, because the original ceiling produced so many echoes that the entire room had to be hung with carpets to dampen the noise. The ceiling was rebuilt in 1902 and only then did the now-famous whispering effect emerge. Another famous whispering gallery—the site of many marriage proposals—is in Grand Central Station in New York City.

Hyperbolas

A hyperbola can also be defined in terms of distances. In the case of a hyperbola, there are two foci and two directrices. Hyperbolas also have two asymptotes.

A hyperbola is the set of all points where the difference between their distances from two fixed points (the foci) is constant.

A graph of a typical hyperbola appears as follows.

The derivation of the equation of a hyperbola in standard form is virtually identical to that of an ellipse. One slight hitch lies in the definition: The difference between two numbers is always positive. Let \(P\) be a point on the hyperbola with coordinates \((x,y)\). Then the definition of the hyperbola gives \(|d(P,F_1)−d(P,F_2)|=constant\). To simplify the derivation, assume that \(P\) is on the right branch of the hyperbola, so the absolute value bars drop. If it is on the left branch, then the subtraction is reversed. The vertex of the right branch has coordinates \((a,0),\) so

\[d(P,F_1)−d(P,F_2)=(c+a)−(c−a)=2a. \nonumber \]

This equation is therefore true for any point on the hyperbola. Returning to the coordinates \((x,y)\) for \(P\):

\[d(P,F_1)−d(P,F_2)=2a \nonumber \]

\[\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}−\sqrt{(x−c)^2+y^2}=2a. \nonumber \]

Isolate the second radical and square both sides:

\[\sqrt{(x−c)^2+y^2}=-2a+\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2} \nonumber \]

\[(x−c)^2+y^2=4a^2-4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+(x+c)^2+y^2 \nonumber \]

\[x^2−2cx+c^2+y^2=4a^2-4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+x^2+2cx+c^2+y^2 \nonumber \]

\[−2cx=4a^2-4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+2cx. \nonumber \]

Now isolate the radical on the right-hand side and square again:

\(−2cx=4a^2-4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}+2cx\)

\(-4a\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}=−4a^2−4cx\)

\(-\sqrt{(x+c)^2+y^2}=−a−\dfrac{cx}{a}\)

\((x+c)^2+y^2=a^2+2cx+\dfrac{c^2x^2}{a^2}\)

\(x^2+2cx+c^2+y^2=a^2+2cx+\dfrac{c^2x^2}{a^2}\)

\(x^2+c^2+y^2=a^2+\dfrac{c^2x^2}{a^2}\).

Isolate the variables on the left-hand side of the equation and the constants on the right-hand side:

\[x^2−\dfrac{c^2x^2}{a^2}+y^2=a^2−c^2 \nonumber \]

\[\dfrac{(a^2−c^2)x^2}{a^2}+y^2=a^2−c^2. \nonumber \]

Finally, divide both sides by \(a^2−c^2\). This gives the equation

\[\dfrac{x^2}{a^2}+\dfrac{y^2}{a^2−c^2}=1. \nonumber \]

We now define b so that \(b^2=c^2−a^2\). This is possible because \(c>a\). Therefore the equation of the hyperbola becomes

\[\dfrac{x^2}{a^2}−\dfrac{y^2}{b^2}=1. \nonumber \]

Finally, if the center of the hyperbola is moved from the origin to the point \((h,k),\) we have the following standard form of a hyperbola.

Consider the hyperbola with center \((h,k)\), a horizontal major axis, and a vertical minor axis. Then the equation of this hyperbola is

\[\dfrac{(x−h)^2}{a^2}−\dfrac{(y−k)^2}{b^2}=1 \label{HorHyperbola} \]

and the foci are located at \((h±c,k),\) where \(c^2=a^2+b^2\). The equations of the asymptotes are given by \(y=k±\dfrac{b}{a}(x−h).\) The equations of the directrices are

\[x=h±\dfrac{a^2}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}=h±\dfrac{a^2}{c} \nonumber \]

If the major axis is vertical, then the equation of the hyperbola becomes

\[\dfrac{(y−k)^2}{a^2}−\dfrac{(x−h)^2}{b^2}=1 \nonumber \]

and the foci are located at \((h,k±c),\) where \(c^2=a^2+b^2\). The equations of the asymptotes are given by \(y=k±\dfrac{a}{b}(x−h)\). The equations of the directrices are

\[y=k±\dfrac{a^2}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}=k±\dfrac{a^2}{c}. \nonumber \]

If the major axis (transverse axis) is horizontal, then the hyperbola is called horizontal, and if the major axis is vertical then the hyperbola is called vertical. The equation of a hyperbola is in general form if it is in the form

\[Ax^2+By^2+Cx+Dy+E=0, \nonumber \]

where A and B have opposite signs. In order to convert the equation from general to standard form, use the method of completing the square.

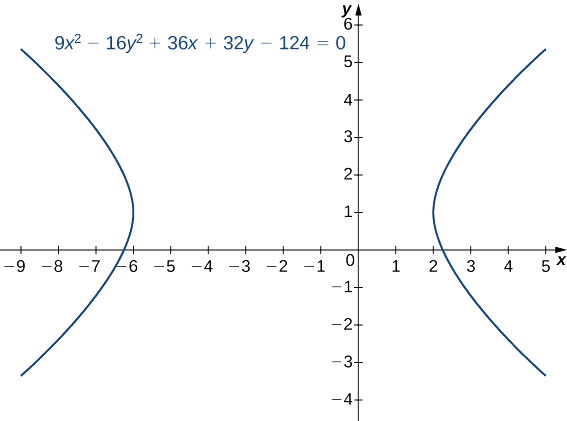

Put the equation \(9x^2−16y^2+36x+32y−124=0\) into standard form and graph the resulting hyperbola. What are the equations of the asymptotes?

Solution

First add \(124\) to both sides of the equation:

\(9x^2−16y^2+36x+32y=124.\)

Next group the \(x\) terms together and the \(y\) terms together, then factor out the common factors:

\((9x^2+36x)−(16y^2−32y)=124\)

\(9(x^2+4x)−16(y^2−2y)=124\).

We need to determine the constant that, when added inside each set of parentheses, results in a perfect square. In the first set of parentheses, take half the coefficient of \(x\) and square it. This gives \(\left(\dfrac{4}{2}\right)^2=4\). In the second set of parentheses, take half the coefficient of \(y\) and square it. This gives \(\left(\dfrac{−2}{2}\right)^2=1.\) Add these inside each pair of parentheses. Since the first set of parentheses has a \(9\) in front, we are actually adding \(36\) to the left-hand side. Similarly, we are subtracting \(16\) from the second set of parentheses. Therefore the equation becomes

\(9(x^2+4x+4)−16(y^2−2y+1)=124+36−16\)

\(9(x^2+4x+4)−16(y^2−2y+1)=144.\)

Next factor both sets of parentheses and divide by \(144\):

\(9(x+2)^2−16(y−1)^2=144\)

\(\dfrac{9(x+2)^2}{144}−\dfrac{16(y−1)^2}{144}=1\)

\(\dfrac{(x+2)^2}{16}−\dfrac{(y−1)^2}{9}=1.\)

The equation is now in standard form. Comparing this to Equation \ref{HorHyperbola} gives \(h=−2, \, k=1, \, a=4,\) and \(b=3\). This is a horizontal hyperbola with center at \((−2,1)\) and asymptotes given by the equations \(y=1±\dfrac{3}{4}(x+2)\). The graph of this hyperbola appears in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\).

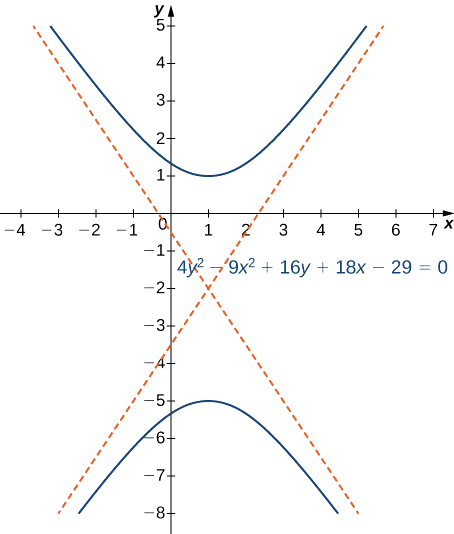

Put the equation \(4y^2−9x^2+16y+18x−29=0\) into standard form and graph the resulting hyperbola. What are the equations of the asymptotes?

- Hint

-

Move the constant over and complete the square. Check which direction the hyperbola opens

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{(y+2)^2}{9}−\dfrac{(x−1)^2}{4}=1.\) This is a vertical hyperbola. Asymptotes \(y=−2±\dfrac{3}{2}(x−1).\)

Hyperbolas also have interesting reflective properties. A ray directed toward one focus of a hyperbola is reflected by a hyperbolic mirror toward the other focus. This concept is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\).

This property of the hyperbola has important applications. It is used in radio direction finding (since the difference in signals from two towers is constant along hyperbolas), and in the construction of mirrors inside telescopes (to reflect light coming from the parabolic mirror to the eyepiece). Another interesting fact about hyperbolas is that for a comet entering the solar system, if the speed is great enough to escape the Sun’s gravitational pull, then the path that the comet takes as it passes through the solar system is hyperbolic.

Eccentricity and Directrix

An alternative way to describe a conic section involves the directrices, the foci, and a new property called eccentricity. We will see that the value of the eccentricity of a conic section can uniquely define that conic.

The eccentricity \(e\) of a conic section is defined to be the distance from any point on the conic section to its focus, divided by the perpendicular distance from that point to the nearest directrix. This value is constant for any conic section, and can define the conic section as well:

- If \(e=1\), the conic is a parabola.

- If \(e<1\), it is an ellipse.

- If \(e>1,\) it is a hyperbola.

The eccentricity of a circle is zero. The directrix of a conic section is the line that, together with the point known as the focus, serves to define a conic section. Hyperbolas and noncircular ellipses have two foci and two associated directrices. Parabolas have one focus and one directrix.

The three conic sections with their directrices appear in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

Recall from the definition of a parabola that the distance from any point on the parabola to the focus is equal to the distance from that same point to the directrix. Therefore, by definition, the eccentricity of a parabola must be 1. The equations of the directrices of a horizontal ellipse are \(x=±\dfrac{a^2}{c}\). The right vertex of the ellipse is located at \((a,0)\) and the right focus is \((c,0)\). Therefore the distance from the vertex to the focus is \(a−c\) and the distance from the vertex to the right directrix is \(\dfrac{a^2}{c}−c.\) This gives the eccentricity as

\[e=\dfrac{a−c}{\dfrac{a^2}{c}−a}=\dfrac{c(a−c)}{a^2−ac}=\dfrac{c(a−c)}{a(a−c)}=\dfrac{c}{a}. \nonumber \]

Since \(c<a\), this step proves that the eccentricity of an ellipse is less than 1. The directrices of a horizontal hyperbola are also located at \(x=±\dfrac{a^2}{c}\), and a similar calculation shows that the eccentricity of a hyperbola is also \(e=\dfrac{c}{a}\). However in this case we have \(c>a\), so the eccentricity of a hyperbola is greater than \(1\).

Determine the eccentricity of the ellipse described by the equation

\(\dfrac{(x−3)^2}{16}+\dfrac{(y+2)^2}{25}=1.\)

Solution

From the equation we see that \(a=5\) and \(b=4\). The value of \(c\) can be calculated using the equation \(a^2=b^2+c^2\) for an ellipse. Substituting the values of \(a\) and \(b\) and solving for \(c\) gives \(c=3\). Therefore the eccentricity of the ellipse is \(e=\dfrac{c}{a}=\dfrac{3}{5}=0.6.\)

Determine the eccentricity of the hyperbola described by the equation

\(\dfrac{(y−3)^2}{49}−\dfrac{(x+2)^2}{25}=1.\)

- Hint

-

First find the values of \(a\) and \(b\), then determine \(c\) using the equation \(c^2=a^2+b^2\).

- Answer

-

\(e=\dfrac{c}{a}=\dfrac{\sqrt{74}}{7}≈1.229\)

Polar Equations of Conic Sections

Sometimes it is useful to write or identify the equation of a conic section in polar form. To do this, we need the concept of the focal parameter. The focal parameter of a conic section \(p\) is defined as the distance from a focus to the nearest directrix. The following table gives the focal parameters for the different types of conics, where \(a\) is the length of the semi-major axis (i.e., half the length of the major axis), \(c\) is the distance from the origin to the focus, and \(e\) is the eccentricity. In the case of a parabola, \(a\) represents the distance from the vertex to the focus.

| Conic | \(e\) | \(p\) |

|---|---|---|

| Ellipse | \(0<e<1\) | \(\dfrac{a^2−c^2}{c}=\dfrac{a(1−e^2)}{c}\) |

| Parabola | \(e=1\) | \(2a\) |

| Hyperbola | \(e>1\) | \(\dfrac{c^2−a^2}{c}=\dfrac{a(e^2−1)}{c}\) |

Using the definitions of the focal parameter and eccentricity of the conic section, we can derive an equation for any conic section in polar coordinates. In particular, we assume that one of the foci of a given conic section lies at the pole. Then using the definition of the various conic sections in terms of distances, it is possible to prove the following theorem.

The polar equation of a conic section with focal parameter \(p\) is given by

\(r=\dfrac{ep}{1±e\cos θ}\) or \(r=\dfrac{ep}{1±e\sin θ}.\)

In the equation on the left, the major axis of the conic section is horizontal, and in the equation on the right, the major axis is vertical. To work with a conic section written in polar form, first make the constant term in the denominator equal to \(1\). This can be done by dividing both the numerator and the denominator of the fraction by the constant that appears in front of the plus or minus in the denominator. Then the coefficient of the sine or cosine in the denominator is the eccentricity. This value identifies the conic. If cosine appears in the denominator, then the conic is horizontal. If sine appears, then the conic is vertical. If both appear then the axes are rotated. The center of the conic is not necessarily at the origin. The center is at the origin only if the conic is a circle (i.e., \(e=0\)).

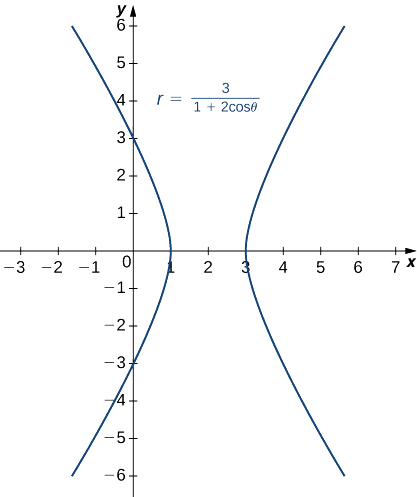

Identify and create a graph of the conic section described by the equation

\(r=\dfrac{3}{1+2\cos θ}\).

Solution

The constant term in the denominator is \(1\), so the eccentricity of the conic is \(2\). This is a hyperbola. The focal parameter \(p\) can be calculated by using the equation \(ep=3.\) Since \(e=2\), this gives \(p=\dfrac{3}{2}\). The cosine function appears in the denominator, so the hyperbola is horizontal. Pick a few values for \(θ\) and create a table of values. Then we can graph the hyperbola (Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)).

| \(θ\) | \(r\) | \(θ\) | \(r\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | \(π\) | −3 |

| \(\dfrac{π}{4}\) | \(\dfrac{3}{1+\sqrt{2}}≈1.2426\) | \(\dfrac{5π}{4}\) | \(\dfrac{3}{1−\sqrt{2}}≈−7.2426\) |

| \(\dfrac{π}{2}\) | 3 | \(\dfrac{3π}{2}\) | 3 |

| \(\dfrac{3π}{4}\) | \(\dfrac{3}{1−\sqrt{2}}≈−7.2426\) | \(\dfrac{7π}{4}\) | \(\dfrac{3}{1+\sqrt{2}}≈1.2426\) |

Identify and create a graph of the conic section described by the equation

\(r=\dfrac{4}{1−0.8 \sin θ}\).

- Hint

-

First find the values of \(e\) and \(p\), and then create a table of values.

- Answer

-

Here \(e=0.8\) and \(p=5\). This conic section is an ellipse.

General Equations of Degree Two

A general equation of degree two can be written in the form

\[ Ax^2+Bxy+Cy^2+Dx+Ey+F=0. \nonumber \]

The graph of an equation of this form is a conic section. If \(B≠0\) then the coordinate axes are rotated. To identify the conic section, we use the discriminant of the conic section \(4AC−B^2.\)

One of the following cases must be true:

- \(4AC−B^2>0\). If so, the graph is an ellipse.

- \(4AC−B^2=0\). If so, the graph is a parabola.

- \(4AC−B^2<0\). If so, the graph is a hyperbola.

The simplest example of a second-degree equation involving a cross term is \(xy=1\). This equation can be solved for \(y\) to obtain \(y=\dfrac{1}{x}\). The graph of this function is called a rectangular hyperbola as shown.

The asymptotes of this hyperbola are the \(x\) and \(y\) coordinate axes. To determine the angle θ of rotation of the conic section, we use the formula \(\cot 2θ=\frac{A−C}{B}\). In this case \(A=C=0\) and \(B=1\), so \(\cot 2θ=(0−0)/1=0\) and \(θ=45°\). The method for graphing a conic section with rotated axes involves determining the coefficients of the conic in the rotated coordinate system. The new coefficients are labeled \(A′,\,B′,\,C′,\,D′,\,E′,\) and \(F′,\) and are given by the formulas

\[ \begin{align*} A′ &=A\cos^ 2θ+B\cos θ\sin θ+C\sin^2 θ \\ B′ &=0 \\ C′ &=A\sin^2 θ−B\sin θ\cos θ+C\cos^2θ \\ D′ &=D\cos θ+E\sin θ \\ E′ &=−D\sin θ+E\cosθ \\ F′ &=F. \end{align*} \]

The procedure for graphing a rotated conic is the following:

- Identify the conic section using the discriminant \(4AC−B^2\).

- Determine \(θ\) using the formula \[\cot2θ=\dfrac{A−C}{B} \label{rot}. \]

- Calculate \(A′,\,B′,\,C′,\,D′,\,E′\), and \(F′\).

- Rewrite the original equation using \(A′,\,B′,\,C′,\,D′,\,E′\), and \(F′\).

- Draw a graph using the rotated equation.

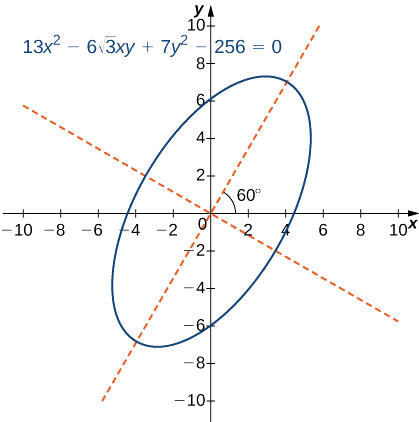

Identify the conic and calculate the angle of rotation of axes for the curve described by the equation

\[13x^2−6\sqrt{3}xy+7y^2−256=0. \nonumber \]

Solution

In this equation, \(A=13,\,B=−6\sqrt{3},\,C=7,\,D=0,\,E=0,\) and \(F=−256\). The discriminant of this equation is

\[4AC−B^2=4(13)(7)−(−6\sqrt{3})^2=364−108=256. \nonumber \]

Therefore this conic is an ellipse.

To calculate the angle of rotation of the axes, use Equation \ref{rot}

\[\cot 2θ=\dfrac{A−C}{B}. \nonumber \]

This gives

\(\cot 2θ=\dfrac{A−C}{B}=\dfrac{13−7}{−6\sqrt{3}}=−\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{3}\).

Therefore \(2θ=120^o\) and \(θ=60^o\), which is the angle of the rotation of the axes.

To determine the rotated coefficients, use the formulas given above:

\(\begin{align*} A′&=A\cos^2θ+B\cos θ\sinθ+C\sin^2θ\\[4pt]

&=13\cos^260+(−6\sqrt{3})\cos 60 \sin 60+7\sin^260\\[4pt]

&=13\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)^2−6\sqrt{3}\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)+7\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^2\\[4pt]

&=4,\end{align*}\)

\(B′=0\)

\(\begin{align*} C′&=A\sin^2θ−B\sin θ\cos θ+C\cos^2θ\\[4pt]

&=13\sin^260+(6\sqrt{3})\sin 60 \cos 60+7\cos^260\\[4pt]

&=13\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^2+6\sqrt{3}\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)+7\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)^2\\[4pt]

&=16,\end{align*}\)

\(\begin{align*} D′&=D\cos θ+E\sin θ\\[4pt]

&=(0)\cos 60+(0)\sin 60\\[4pt]

&=0,\end{align*}\)

\(\begin{align*} E′&=−D\sin θ+E\cos θ\\[4pt]

&=−(0)\sin 60+(0)\cos 60\\[4pt]

&=0\end{align*}\)

\(\begin{align*} F′&= F\\[4pt]

&=−256.\end{align*}\)

The equation of the conic in the rotated coordinate system becomes

\(4(x′)^2+16(y′)^2=256\)

\(\dfrac{(x′)^2}{64}+\dfrac{(y′)^2}{16}=1\).

A graph of this conic section appears as follows.

Identify the conic and calculate the angle of rotation of axes for the curve described by the equation

\[3x^2+5xy−2y^2−125=0. \nonumber \]

- Hint

-

Follow steps 1 and 2 of the five-step method outlined above

- Answer

-

The conic is a hyperbola and the angle of rotation of the axes is \(θ=22.5°.\)

Key Concepts

- The equation of a vertical parabola in standard form with given focus and directrix is \(y=\dfrac{1}{4p}(x−h)^2+k\) where \(p\) is the distance from the vertex to the focus and \((h,k)\) are the coordinates of the vertex.

- The equation of a horizontal ellipse in standard form is \(\dfrac{(x−h)^2}{a^2}+\dfrac{(y−k)^2}{b^2}=1\) where the center has coordinates \((h,k)\), the major axis has length \(2a\), the minor axis has length \(2b\), and the coordinates of the foci are \((h±c,k)\), where \(c^2=a^2−b^2\).

- The equation of a horizontal hyperbola in standard form is \(\dfrac{(x−h)^2}{a^2}−\dfrac{(y−k)^2}{b^2}=1\) where the center has coordinates \((h,k)\), the vertices are located at \((h±a,k)\), and the coordinates of the foci are \((h±c,k),\) where \(c^2=a^2+b^2\).

- The eccentricity of an ellipse is less than \(1\), the eccentricity of a parabola is equal to \(1\), and the eccentricity of a hyperbola is greater than \(1\). The eccentricity of a circle is \(0\).

- The polar equation of a conic section with eccentricity \(e\) is \(r=\dfrac{ep}{1±e\cos θ}\) or \(r=\dfrac{ep}{1±e\sin θ}\), where \(p\) represents the focal parameter.

- To identify a conic generated by the equation \(Ax^2+Bxy+Cy^2+Dx+Ey+F=0\),first calculate the discriminant \(D=4AC−B^2\). If \(D>0\) then the conic is an ellipse, if \(D=0\) then the conic is a parabola, and if \(D<0\) then the conic is a hyperbola.

Glossary

- conic section

- a conic section is any curve formed by the intersection of a plane with a cone of two nappes

- directrix

- a directrix (plural: directrices) is a line used to construct and define a conic section; a parabola has one directrix; ellipses and hyperbolas have two

- discriminant

- the value \(4AC−B^2\), which is used to identify a conic when the equation contains a term involving \(xy\), is called a discriminant

- focus

- a focus (plural: foci) is a point used to construct and define a conic section; a parabola has one focus; an ellipse and a hyperbola have two

- eccentricity

- the eccentricity is defined as the distance from any point on the conic section to its focus divided by the perpendicular distance from that point to the nearest directrix

- focal parameter

- the focal parameter is the distance from a focus of a conic section to the nearest directrix

- general form

- an equation of a conic section written as a general second-degree equation

- major axis

- the major axis of a conic section passes through the vertex in the case of a parabola or through the two vertices in the case of an ellipse or hyperbola; it is also an axis of symmetry of the conic; also called the transverse axis

- minor axis

- the minor axis is perpendicular to the major axis and intersects the major axis at the center of the conic, or at the vertex in the case of the parabola; also called the conjugate axis

- nappe

- a nappe is one half of a double cone

- standard form

- an equation of a conic section showing its properties, such as location of the vertex or lengths of major and minor axes

- vertex

- a vertex is an extreme point on a conic section; a parabola has one vertex at its turning point. An ellipse has two vertices, one at each end of the major axis; a hyperbola has two vertices, one at the turning point of each branch