3.1: Double and Iterated Integrals Over Rectangles

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

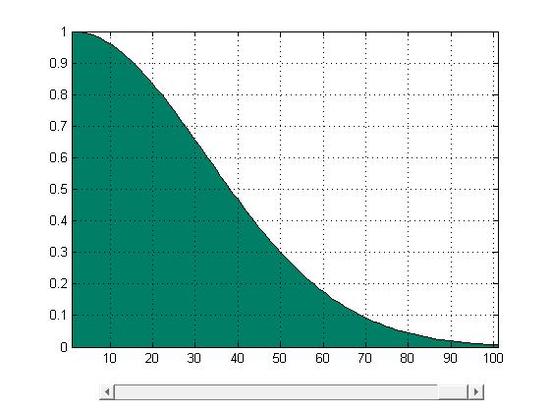

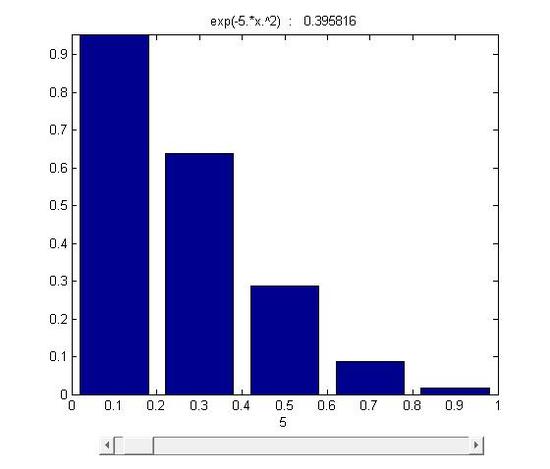

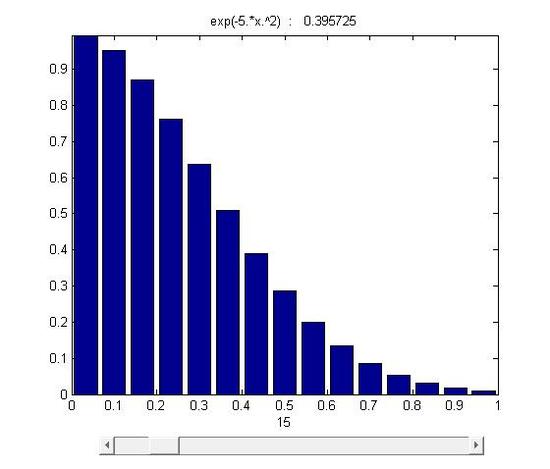

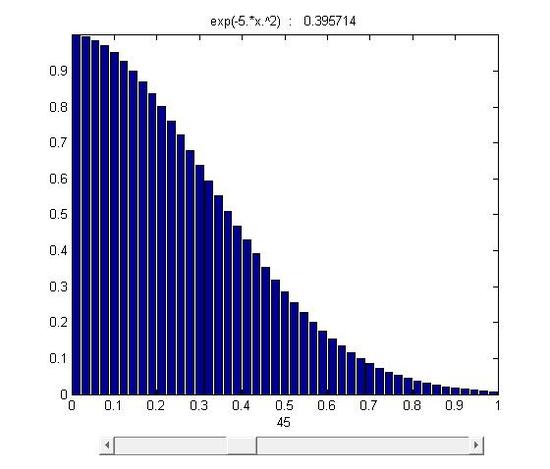

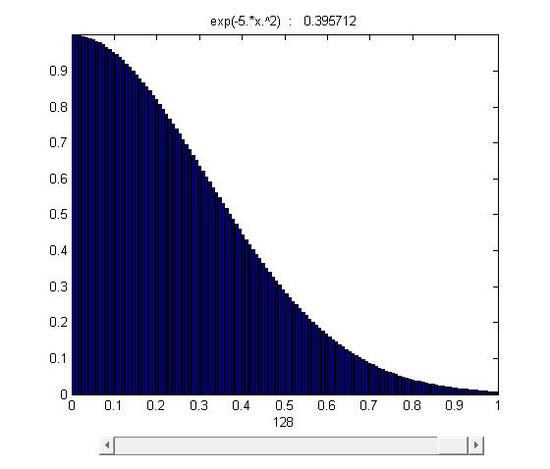

y=f(x)=e−5x2,0≤x≤1

∫baf(x)dx=limn→∞n∑i=1f(xi)Δxi

A fundamental method to calculate the area: the base of function f(x) is equally divide into n pieces whose width are Δx. Then S=Δxf(xi) is the area of the rectangle at the location Δxi and its height is f(xi) among the range Δxi. Through summing all these rectangular pieces together, we can roughly estimate the area under the function f(x) in its domain. The equation ∑ni=1f(xi)Δxi can be used to represent this process.

However, ∑ni=1f(xi)Δxi can only help us to estimate the value, which means errors still exist. In this case, limits help us to fix the problem.

figure 15.1-1

As it was mentioned, the area was divided into n stripes. As n→∞ and Δx→0, stripesΔxf(xi)approachs to a line whose length is equal to the height of f(xi). Eventually, through infinite division and accumulation, the error is reduced to zero and the sum of f(x)Δx equals to the area under the curve.

∫baf(x)dx=limn→∞n∑i=1f(xi)Δxi

Thus, we can conclude that the integral is the function of accumulation as it accumulates infinite number of strips in a certain domain to calculate the area. Similarly, the double integral is also a function of accumulation. It accumulates infinite number of small 3D strips to calculate the volume of 3D objects.

V=∫∫Rf(xi,yi)dx=limn→∞n∑k=1f(xi,yi)ΔAi

R is the domain of the function (the area that you want to integrate over)

Explanation:as n→∞, the number of strips goes to infinity, ΔA→∞, the error of calculation goes to 0 and the accumulation of these infinite strips eventually equals the volume of the objects.

Theoretical discussion with descriptive elaboration

If f(x,y) is contunuous throughout the rectangular region R: a≤x≤b,c≤y≤d,

then

∫∫Rf(x,y)ΔA=∫dc∫baf(x,y)ΔxΔy=∫ba∫dcf(x,y)ΔyΔx.

Fubini's Theorem is usually used to calculate the volume of three dimensional bodies

Vi=f(xi,yi)ΔAi=f(xi,yi)ΔxΔy

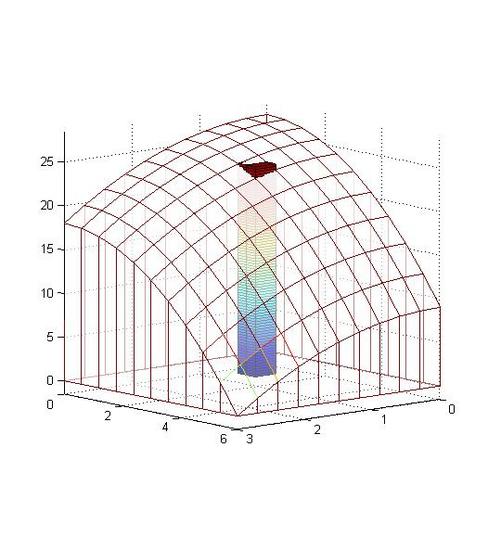

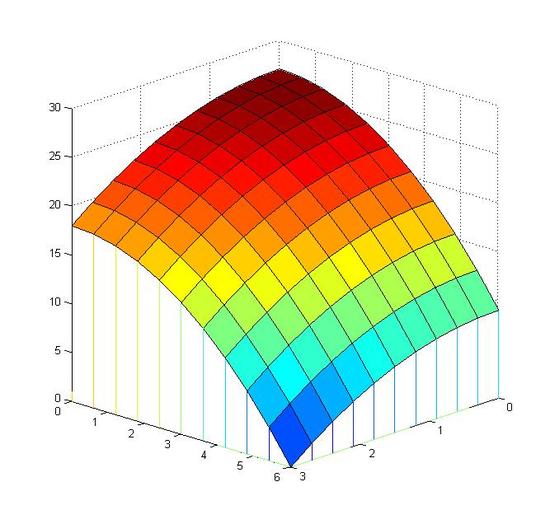

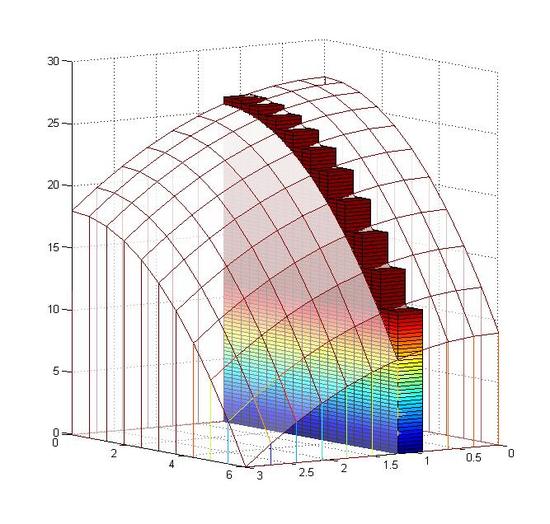

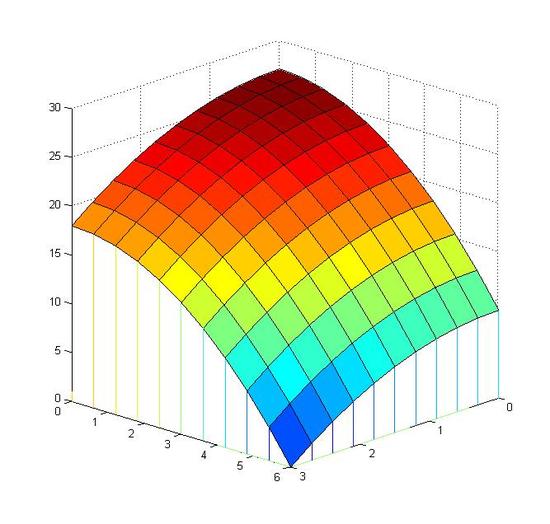

In figure 15.1-2 , f(xi,yi) is the height of the cuboid and ΔA is its base. Vi means that at different location, there is a corresponding cuboid whose height is closed to the average height of the graph at the area ΔAi.

At the specific Δyi, the cuboids with different Δxi are lined up to form a layer.

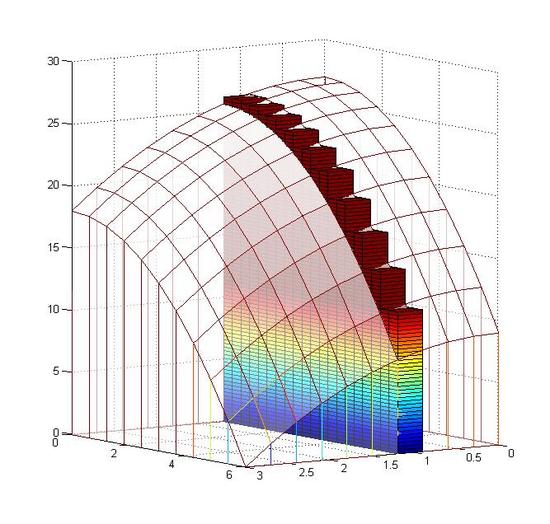

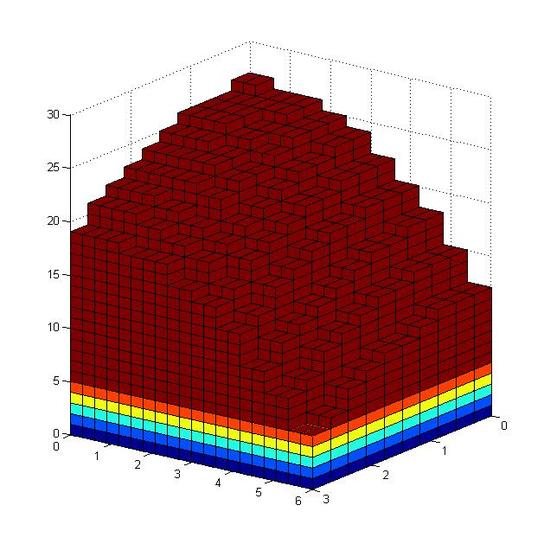

V=n∑i=1f(xi,yi)ΔAi=n∑i=1f(xi,yi)ΔxiΔyi

As all the layers are combined together, we get a body that is approximated to the one in the next graph, but the error is still very large.

V=limn→∞n∑i=1f(xi,yi)ΔAi

Limit helps to solve this problem. As n goes to infinity, ΔAi becomes smaller eventually turns to a dot. f(xi,yi)ΔAi becomes a line and error of volume decreases to zero. Thus, the accumulation of all these lines equal to the volume.

Now we can calculate the volume below the function f(x,y)=27−x2−12y2dxdy and above f(x,y), in the domain 0≤x≤3 and 0≤y≤6.

∫60∫3027−x2−12y2dxdy=∫60(27−12y2)x−13x3|30dy=∫60[(27−12y2)×3−13×33=∫6072−32y2 dy=[72y−12y3]|60=(72×6−12×63)−(0−0)=324

Figure: (left) from step 1 to step 3 (right) from step 3 to step 6

Another way to calculate the volume of the graph:

∫30∫6027−x2−12y2dydx=∫30(27−x2)y−16y3|60 dx=∫30[(27−x2)×6−16×63]−[0−0] dx=∫30126−6x2 dx=[126x−2x3]|30=(126×3−2×33)−(0−0)=324.

Find the volume that is bounded above by the surface z=f(x,y)=x2+y2 and below by a rectangule R: 0≤x≤2,0≤y≤3.

∫20∫30x2+y2dydx=∫20x2y+13y3|30dx=∫203x2+9dx=x3+9x|20=(8+18)−0=26

Contributors and Attributions

Integrated by Justin Marshall.