12.3: Paths and Cycles

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Recall the definition of a walk. As we saw in Example 12.2.1, the vertices and edges in a walk do not need to be distinct.

There are many circumstances under which we might not want to allow edges or vertices to be re-visited. Efficiency is one possible reason for this. We have a special name for a walk that does not allow vertices to be re-visited.

Definition: Path

A walk in which no vertex appears more than once is called a path.

Notation

For

Notice that if an edge were to appear more than once in a walk, then both of its endvertices would also have to appear more than once, so a path does not allow vertices or edges to be re-visited.

Example

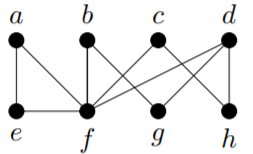

In the graph

Proposition

Suppose that

- Proof

-

Since

Towards a contradiction, suppose that we have a

and

Since consecutive vertices were adjacent in the first sequence, they are also adjacent in the second sequence, so the second sequence is a walk. The length of the first walk is

This allows us to prove another interesting fact that will be useful later.

Proposition

Deleting an edge from a connected graph can never result in a graph that has more than two connected components.

- Proof

-

Let

Let

Let

Since

A cycle is like a path, except that it starts and ends at the same vertex. The structures that we will call cycles in this course, are sometimes referred to as circuits.

Definition: Cycle

A walk of length at least

Notation

For

The requirement that the walk have length at least

Example

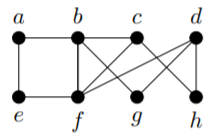

In the graph from Example 12.3.1,

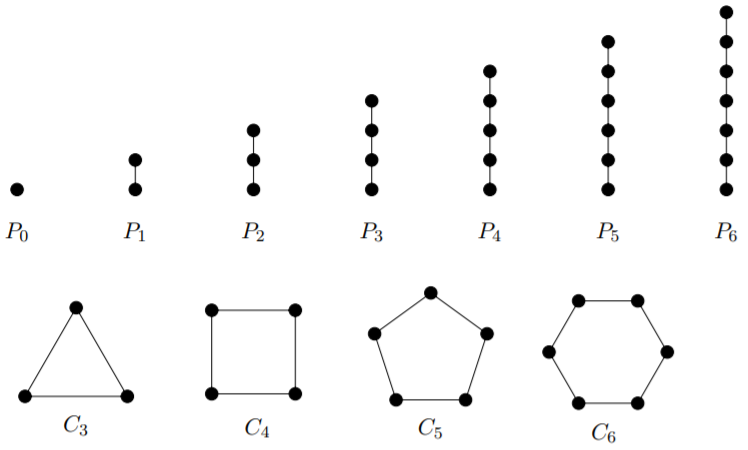

Here are drawings of some small paths and cycles:

We end this section with a proposition whose proof will be left as an exercise.

Proposition

Suppose that

Exercise

1) In the graph

(a) Find a path of length

(b) Find a cycle of length

(c) Find a walk of length

2) Prove that in a graph, any walk that starts and ends with the same vertex and has the smallest possible non-zero length, must be a cycle.

3) Prove Proposition 12.3.3.

4) Prove by induction that if every vertex of a connected graph on

5) Let