The general nonlinear partial differential equation of second order is

where , , and stands for all second derivatives. The function is given and sufficiently regular with respect to its arguments.

In this section we consider the case

The equation is linear if

Concerning the classification the main part

plays the essential role. Suppose , then we can assume, without restriction of generality, that , since

where

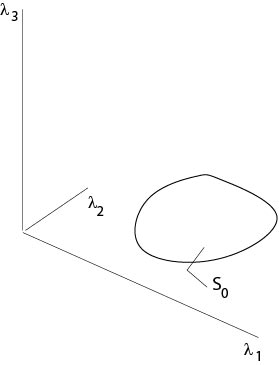

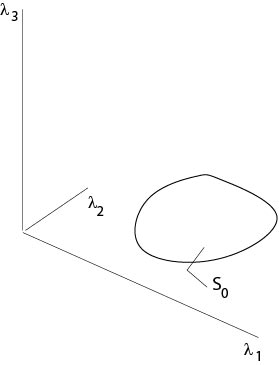

Consider a hypersurface in defined implicitly by , , see Figure 3.1.1

Figure 3.1.1: Initial Manifold

Assume and are given on .

Problem: Can we calculate all other derivatives of on by using differential equation (\) and the given data?

We will find an answer if we map onto a hyperplane by a mapping

for functions such that

in . It is assumed that and are sufficiently regular. Such a mapping exists, see an exercise.

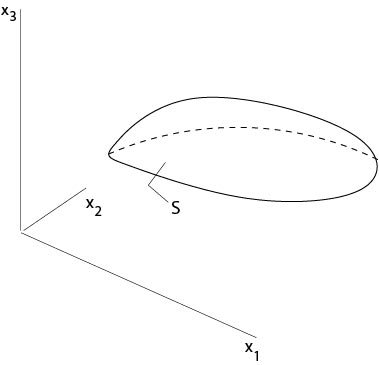

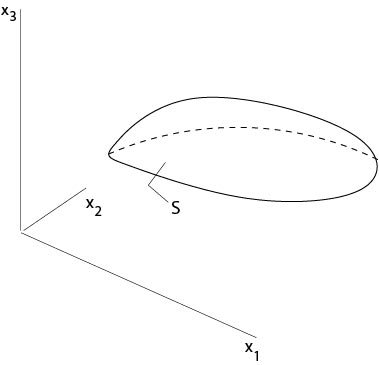

The above transform maps onto a subset of the hyperplane defined by , see Figure 3.1.2.

Figure 3.1.2: Transformed flat manifold

We will write the differential equation in these new coordinates. Here we use Einstein's convention, that is, we add terms with repeating indices. Since

where and , we get

Then the differential equation () in the new coordinates is given by

Since , , are known, see (), it follows that , , are known on . Thus we know all second derivatives on with the only exception of .

We recall that, provided is sufficiently regular,

is the limit of

as .

Then the differential equation can be written as

It follows that we can calculate if

on . This is a condition for the given equation and for the given surface .

Definition. The differential equation

is called it characteristic differential equation associated to the given differential equation ().

If , , is a solution of the characteristic differential equation, then the surface defined by is called characteristic surface.

Remark. The condition () is satisfied for each with if the quadratic matrix is positive or negative definite for each , which is equivalent to the property that all eigenvalues are different from zero and have the same sign. This follows since there is a such that, in the case that the matrix is poitive definite,

for all . Here and in the following we assume that the matrix is real and symmetric.

The characterization of differential equation () follows from the signs of the eigenvalues of .

Definition. The differential equation () is said to be of type at if eigenvalues of are positive, eigenvalues are negative and eigenvalues are zero ().

In particular, the equation is called

elliptic if it is of type or of type , that is, all eigenvalues are different from zero and have the same sign,\

parabolic if it is of type or of type , that is, one eigenvalue is zero and all the others are different from zero and have the same sign,

hyperbolic if it is of type or of type , that is, all eigenvalues are different from zero and one eigenvalue has another sign than all the others.

Remarks:

1. According to this definition there are other types aside from elliptic, parabolic or hyperbolic equations.

2. The classification depends in general on . An example is the Tricomi equation, which appears in the theory of transsonic flows,

This equation is elliptic if , parabolic if and hyperbolic for .

Examples:

Example 3.1.1:

The Laplace equation in is , where

This equation is elliptic since for every manifold given by , where is an arbitrary sufficiently regular function such that , all derivatives of are known on , provided and are known on .

Example 3.1.2:

The wave equation , where , is hyperbolic. Such a type describes oscillations of mechanical structures, for example.

Example 3.1.3:

The heat equation , where , is

parabolic. It describes, for example, the propagation of heat in a domain.

Example 3.1.4:

Consider the case that the (real) coefficients in equation () are {\it constant}. We recall that the matrix is symmetric, that is, . In this case, the transform to principle axis leads to a normal form from which the classification of the equation is obviously. Let be the associated orthogonal matrix, then

Here is , where , , is an orthonormal system of eigenvectors to the eigenvalues .

Set and , then

Contributors and Attributions