20.4: Vanishing Area and Subdivisions

- Page ID

- 23713

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Any one-point set as well as any segment in the Euclidean plane have vanishing area.

- Proof

-

Fix a line segment \([AB]\). Consider a sold square \(\blacksquare ABCD\).

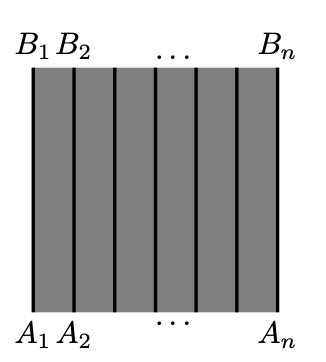

Note that given a positive integer \(n\), there are \(n\) disjoint segments \([A_1B_1],\dots,[A_nB_n]\) in \(\blacksquare ABCD\), such that each \([A_iB_i]\) is congruent to \([AB]\) in the sense of the Definition 20.1.1.

Applying invariance, additivity, and monotonicity of the area function, we get that

\(\begin{aligned} n\cdot \text{area }[AB] &=\text{area }\left([A_1B_1]\cup\dots\cup[A_nB_n]\right)\le \\ &\le \text{area }(\blacksquare ABCD) \end{aligned}\)

That is,

\(\text{area }[AB]\le \tfrac1n\cdot\text{area }(\blacksquare ABCD)\)

for any positive integer \(n\). Therefore, \(\text{area }[AB]\le 0\). On the other hand, by definition of area, \(\text{area }[AB]\ge 0\), hence

\(\text{area }[AB]= 0.\)

For any one-point set \(\{A\}\) we have that \(\{A\}\subset [AB]\). Therefore,

\(0\le \text{area }\{A\}\le \text{area }[AB]=0.\)

Whence \(\text{area }\{A\}=0\).

Any degenerate polygonal set has vanishing area.

- Proof

-

Let \(\mathcal P\) be a degenerate set, say

Since area is nonnegative by definition, applying additivity several times, we get that

\(\begin{aligned} \text{area }\mathcal{P}\le & \text{area }[A_1B_1]+\dots+\text{area }[A_nB_n]+ \\ &+\text{area }\{C_1\}+\dots+\text{area }\{C_k\}.\end{aligned}\)

By Proposition \(\PageIndex{1}\), the right hand side vanishes.

On the other hand, \(\text{area }\mathcal{P}\ge 0\), hence the result.

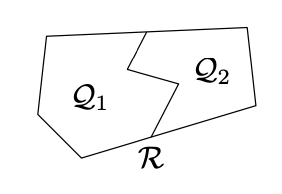

We say that polygonal set \(\mathcal{P}\) is subdivided into two polygonal sets \(\mathcal{Q}_1,\dots,\mathcal{Q}_n\) if \(\mathcal{P}=\mathcal{Q}_1\cup\dots\cup \mathcal{Q}_n\) and the intersection \(\mathcal{Q}_i\cap\mathcal{Q}_j\) is degenerate for any pair \(i\) and \(j\). (Recall that according to Claim20.3.1, the intersections \(\mathcal{Q}_i\cap\mathcal{Q}_j\) are polygonal.)

Assume polygonal sets \(\mathcal{P}\) is subdivided into polygonal sets \(\mathcal{Q}_1, \dots, \mathcal{Q}_n\). Then

\(\text{area }\mathcal{P}=\text{area }\mathcal{Q}_1+\dots+\text{area }\mathcal{Q}_n.\)

- Proof

-

Assume \(n=2\); by additivity of area,

\(\text{area }\mathcal{P}=\text{area }\mathcal{Q}_1+\text{area }\mathcal{Q}_2-\text{area }(\mathcal{Q}_1 \cap\mathcal{Q}_2).\)

Since \(\mathcal{Q}_1\cap\mathcal{Q}_2\) is degenerate, by Corollary \(\PageIndex{1}\),

\(\text{area }(\mathcal{Q}_1\cap\mathcal{Q}_2)=0.\)

Applying this formula a few times we get the general case. Indeed, if \(\mathcal{P}\) is subdivided into \(\mathcal{Q}_1,\dots,\mathcal{Q}_n\), then

\(\begin{aligned} \text{area }\mathcal{P}&=\text{area }\mathcal{Q}_1+\text{area }(\mathcal{Q}_2\cup\dots\cup\mathcal{Q}_n)= \\ &=\text{area }\mathcal{Q}_1+\text{area } \mathcal{Q}_2+\text{area }( \mathcal{Q}_3\cup\dots\cup\mathcal{Q}_n)= \\ &\ \ \ \vdots \\ &=\text{area }\mathcal{Q}_1+\text{area } \mathcal{Q}_2+\dots+\text{area }\mathcal{Q}_n.\end{aligned}\)

Two polygonal sets \(\mathcal{P}\) and \(\mathcal{P}'\) are called equidecomposable if they admit subdivisions into polygonal sets \(\mathcal{Q}_1,\dots,\mathcal{Q}_n\) and \(\mathcal{Q}'_1,\dots,\mathcal{Q}'_n\) such that \(\mathcal{Q}_i\cong\mathcal{Q}'_i\) for each \(i\).

According to the proposition, if \(\mathcal{P}\) and \(\mathcal{P}\) are equidecomposable, then \(\text{area } \mathcal{P}=\text{area }\mathcal{P}'\). A converse to this statement also holds; namely if two nondegenerate polygonal sets have equal area, then they are equidecomposable.

The last statement was proved by William Wallace, Farkas Bolyai and Paul Gerwien. The analogous statement in three dimensions, known as Hilbert’s third problem, is false; it was proved by Max Dehn.