5.4: Multiplying Decimals

- Page ID

- 22490

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Multiplying decimal numbers involves two steps: (1) multiplying the numbers as whole numbers, ignoring the decimal point, and (2) placing the decimal point in the correct position in the product or answer.

For example, consider (0.7)(0.08), which asks us to find the product of “seven tenths” and “eight hundredths.” We could change these decimal numbers to fractions, then multiply.

\[ \begin{aligned} (0.7)(0.8) & = \frac{7}{10} \cdot \frac{8}{100} \\ & = \frac{56}{100} \\ & = 0.056 \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

The product is 56/1000, or “fifty six thousandths,” which as a decimal is written 0.056.

Important Observations

There are two very important observations to be made about the example (0.7)(0.08).

1. In fractional form

\[\frac{7}{10} \cdot \frac{8}{100} = \frac{56}{1000},\nonumber \]

note that the numerator of the product is found by taking the product of the whole numbers 7 and 8. That is, you ignore the decimal points in 0.7 and 0.08 and multiply 7 and 8 as if they were whole numbers.

2. The first factor, 0.7, has one digit to the right of the decimal point. Its fractional equivalent, 7/10, has one zero in its denominator. The second factor, 0.08, has two digits to the right of the decimal point. Its fractional equivalent, 8/100, has two zeros in its denominator. Therefore, the product 56/1000 is forced to have three zeros in its denominator and its decimal equivalent, 0.056, must therefore have three digits to the right of the decimal point.

Let’s look at another example.

Simplify: (2.34)(1.2).

Solution

Change the decimal numbers “two and thirty four hundredths” and “one and two tenths” to fractions, then multiply.

\[ \begin{aligned} (2.34)(1.2) = 2 \frac{34}{100} \cdot 1 \frac{2}{10} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Change decimals to fractions.}} \\ = \frac{234}{100 \cdot \frac{12}{10} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Change mixed to improper fractions.}} \\ = \frac{2808}{1000} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators and denominators.}} \\ = 2 \frac{808}{1000} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Change to mixed fraction.}} \\ = 2.808 ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Change back to decimal form.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Multiply: (1.86)(9.5)

- Answer

-

17.67

Important Observations

We make the same two observations as in the previous example.

- If we treat the decimal numbers as whole numbers without decimal points, then (234)(12) = 2808, which is the numerator of the fraction 2808/1000 in the solution shown in Example 1. These are also the same digits shown in the answer 2.808.

- There are two digits to the right of the decimal point in the first factor 2.34 and one digit to the right of the decimal point in the second factor 1.2. This is a total of three digits to the right of the decimal points in the factors, which is precisely the same number of digits that appear to the right of the decimal point in the answer 2.808.

The observations made at the end of the previous two examples lead us to the following method.

To multiply two decimal numbers, perform the following steps:

- Ignore the decimal points in the factors and multiply the two factors as if they were whole numbers.

- Count the number of digits to the right of the decimal point in each factor. Sum these two numbers.

- Place the decimal point in the product so that the number of digits to the right of the decimal point equals the sum found in step 2.

Use the steps outlined in Multiplying Decimal Numbers to find the product in Example 1.

Solution

We follow the steps outlined in Multiplying Decimal Numbers.

1. The first step is to multiply the factors 2.34 and 1.2 as whole numbers, ignoring the decimal points.

\[ \begin{array}{r} 234 \\ \times 12 \\ \hline 468 \\ 234 \\ \hline 2808 \end{array}\nonumber \]

2. The second step is to find the sum of the number of digits to the right of the decimal points in each factor. Note that 2.34 has two digits to the right of the decimal point, while 1.2 has one digit to the right of the decimal point. Thus, we have a total of three digits to the right of the decimal points in the factors.

3. The third and final step is to place the decimal point in the product or answer so that there are a total of three digits to the right of the decimal point. Thus,

(2.34)(1.2) = 2.808.

Note that this is precisely the same solution found in Example 1.

What follows is a convenient way to arrange your work in vertical format.

\[ \begin{array}{r} 2.34 \\ \times 1.2 \\ \hline 468 \\ 2 ~ 34 \\ \hline 2.808 \end{array}\nonumber \]

Multiply: (5.98)(3.7)

- Answer

-

22.126

Simplify: (8.235)(2.3).

Solution

We use the convenient vertical format introduced at the end of Example 2.

\[ \begin{array}{r} 8.235 \\ \times 2.3 \\ \hline 2~4705 \\ 16 ~ 470 \\ \hline 18.9405 \end{array}\nonumber \]

The factor 8.235 has three digits to the right of the decimal point; the factor 2.3 has one digit to the right of the decimal point. Therefore, there must be a total of four digits to the right of the decimal point in the product or answer.

Multiply: (9.582)(8.6)

- Answer

-

82.4052

Multiplying Signed Decimal Numbers

The rules governing multiplication of signed decimal numbers are identical to the rules governing multiplication of integers.

Like Signs. The product of two decimal numbers with like signs is positive. That is:

(+)(+) = + and (−)(−) = +

Unlike Signs. The product of two decimal numbers with unlike signs is negative. That is:

(+)(−) = − and (−)(+) = −

Simplify: (−2.22)(−1.23).

Solution

Ignore the signs to do the multiplication, then consider the signs in the final answer behind.

As each factor has two digits to the right of the decimal point, there should be a total of 4 decimals to the right of the decimal point in the product.

\[ \begin{array}{r} 2.22 \\ \times 1.23 \\ \hline \\ 666 \\ 444 \\ 1~11 \\ \hline 1.6206 \end{array}\nonumber \]

Like signs give a positive product. Hence:

(−2.22)(−1.23) = 1.6206

Multiply: (−3.86)(−5.77)

- Answer

-

22.2722

Simplify: (5.68)(−0.012).

Solution

Ignore the signs to do the multiplication, then consider the signs in the final answer below.

The first factor has two digits to the right of the decimal point, the second factor has three. Therefore, there must be a total of five digits to the right of the decimal point in the product or answer. This necessitates prepending an extra zero in front of our product.

\[ \begin{array}{r} 5.68 \\ \times 0.012 \\ \hline 1136 \\ 568 \\ \hline 0.06816 \end{array}\nonumber \]

Unlike signs give a negative product. Hence:

(5.68)(−0.012) = −0.06816

Multiply: (9.23)(−0.018)

- Answer

-

−0.16614

Order of Operations

The same Rules Guiding Order of Operations also apply to decimal numbers.

When evaluating expressions, proceed in the following order.

- Evaluate expressions contained in grouping symbols first. If grouping symbols are nested, evaluate the expression in the innermost pair of grouping symbols first.

- Evaluate all exponents that appear in the expression.

- Perform all multiplications and divisions in the order that they appear in the expression, moving left to right.

- Perform all additions and subtractions in the order that they appear in the expression, moving left to right.

If a = 3.1 and b = −2.4, evaluate a2 − 3.2b2

Solution

Prepare the expression for substitution using parentheses.

\[a^2 − 3.2b^2 = (~)^2 − 3.2(~)^2\nonumber \]

Substitute 3.1 for a and −2.4 for b and simplify.

\[ \begin{aligned} a^2 - 3.2b^2 = (3.1)^2 -3.2(-2.4)^2 ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Substitute: 3.1 for } a, ~ -2.4 \text{ for } b.} \\ =9.61 - 3.2(5.76) ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Exponents first: } (3.1)^2 = 9.61,~ (-2.4)^2 = 5.76} \\ =9.61 - 18.432 ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply: } 3.2(5.76)=18.432} \\ = -8.822 ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Subtract: } 9.61 - 18.432 = -8.822} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

If a = 3.8 and b = −4.6, evaluate the expression: 2.5a2 − b2

- Answer

-

14.94

Powers of Ten

Consider:

\[ \begin{array}{l}10^1 = 10 \\ 10^2 = 10 \cdot 10 = 100 \\ 10^3 = 10 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 = 1,000 \\ 10^4 = 10 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 = 10,000 \end{array}\nonumber \]

Note the answer for 104, a one followed by four zeros! Do you see the pattern?

In the expression 10n, the exponent matches the number of zeros in the answer. Hence, 10n will be a 1 followed by n zeros.

Simplify: 109.

Solution

109 should be a 1 followed by 9 zeros. That is,

\[10^9 = 1, 000, 000, 000,\nonumber \]

or “one billion.”

Simplify: 106

- Answer

-

1,000,000

Multiplying Decimal Numbers by Powers of Ten

Let’s multiply 1.234567 by 103, or equivalently, by 1,000. Ignore the decimal point and multiply the numbers as whole numbers.

\[ \begin{array}{r} 1.234567 \\ \times 1000 \\ \hline 1234.567000 \end{array}\nonumber \]

The sum total of digits to the right of the decimal point in each factor is 6. Therefore, we place the decimal point in the product so that there are six digits to the right of the decimal point.

However, the trailing zeros may be removed without changing the value of the product. That is, 1.234567 times 1000 is 1234.567. Note that the decimal point in the product is three places further to the right than in the original factor. This observation leads to the following result.

Multiplying a decimal number by 10n will move the decimal point n places to the right.

Simplify: 1.234567 · 104

Solution

Multiplying by 104 (or equivalently, by 10,000) moves the decimal 4 places to the right. Thus, 1.234567 · 10, 000 = 12345.67.

Simplify: 1.234567 · 102

- Answer

-

123.4567

The Circle

Let's begin with a definition.

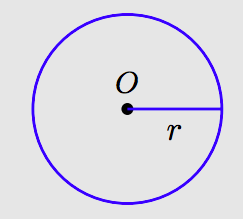

A circle is the collection of all points equidistant from a given point O, called the center of the circle.

The segment joining any point on the circle to the center of the circle is called a radius of the circle. In the figure above, the variable r represents the length of the radius of the circle

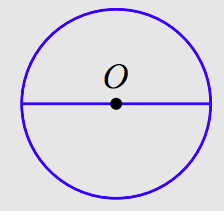

We need another term, the diameter of a circle.

If two points on a circle are connected with a line segment, then that segment is called a chord of the circle. If the chord passes through the center of the circle, then the chord is called the diameter of the circle.

In the figure above, the variable d represents the length of the diameter of the circle. Note that the diameter is twice the length of the radius; in symbols

\[d=2r.\nonumber \]

The Circumference of a Circle

When we work with polygons, the perimeter of the polygon is found by summing the lengths of its edges. The circle uses a different name for its perimeter.

The length of the circle is called its circumference. We usually use the variable C to denote the circumference of a circle

That is, if one were to walk along the circle, the total distance traveled in one revolution is the circumference of the circle.

The ancient mathematicians of Egypt and Greece noted a striking relation between the circumference of a circle and its diameter. They discovered that whenever you divide a circle’s circumference by its diameter, you get a constant. That is, if you take a very large circle and divide its circumference by its diameter, you get exactly the same number if you take a very small circle and divide its circumference by its diameter. This common constant was named π (“pi”).

Whenever a circle’s circumference is divided by its diameter, the answer is the constant π. That is, if C is the circumference of the circle and d is the circle’s diameter, then

\[\frac{C}{d} = \pi.\nonumber \]

In modern times, we usually multiply both sides of this equation by d to obtain the formula for the circumference of a circle.

\[C = \pi d\nonumber \]

Because the diameter of a circle is twice the length of its radius, we can substitute d = 2r in the last equation to get an alternate form of the circumference equation.

\[C = \pi (2r) = 2 \pi r\nonumber \]

The number π has a rich and storied history. Ancient geometers from Egypt, Babylonia, India, and Greece knew that π was slightly larger than 3. The earliest known approximations date from around 1900 BC (Wikipedia); they are 25/8 (Babylonia) and 256/81 (Egypt). The Indian text Shatapatha Brahmana gives π as 339/108 ≈ 3.139. Archimedes (287-212 BC) was the first to estimate π rigorously, approximating the circumference of a circle with inscribed and circumscribed polygons. He was able to prove that 223/71 < π < 22/7. Taking the average of these values yields π ≈ 3.1419. Modern mathematicians have proved that π is an irrational number, an infinite decimal that never repeats any pattern. Mathematicians, with the help of computers, routinely produce approximations of π with billions of digits after the decimal point.

Here is π, correct to the first fifty digits.

π = 3.14159265358979323846264338327950288419716939937510 ...

The number of digits of π used depends on the application. Working at very small scales, one might keep many digits of π, but if you are building a circular garden fence in your backyard, then fewer digits of π are needed.

Find the circumference of a circle given its radius is 12 feet.

Solution

The circumference of the circle is given by the formula C = πd, or, because d = 2r,

\[C = 2πr.\nonumber \]

Substitute 12 for r.

\[C = 2πr = 2π(12) = 24π\nonumber \]

Therefore, the circumference of the circle is exactly C = 24π feet.

We can approximate the circumference by entering an approximation for π. Let’s use π ≈ 3.14. Note: The symbol ≈ is read “approximately equal to.”

\[C = 24π ≈ 24(3.14) ≈ 75.36 \text{ feet}\nonumber \]

It is important to understand that the solution C = 24π feet is the exact circumference, while C ≈ 75.36 feet is only an approximation.

Find the radius of a circle having radius 14 inches. Use π ≈ 3.14

- Answer

-

87.92 inches

The Area of a Circle

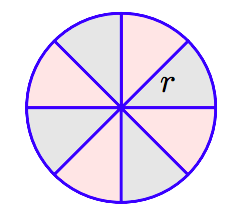

Here’s a reasonable argument used to help develop a formula for the area of a circle. Start with a circle of radius r and divide it into 8 equal wedges, as shown in the figure that follows.

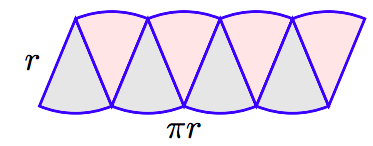

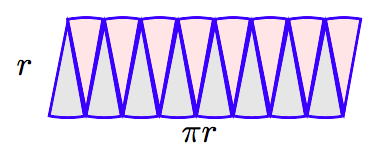

Rearrange the pieces as shown in the following figure.

Note that the rearranged pieces almost form a rectangle with length approximately half the circumference of the circle, πr, and width approximately r. The area would be approximately A ≈ (length)(width) ≈ (πr)(r) ≈ πr2. This approximation would be even better if we doubled the number of wedges of the circle.

If we doubled the number of wedges again, the resulting figure would even more closely resemble a rectangle with length πr and width r. This leads to the following conclusion.

The area of a circle of radius r is given by the formula

\[A = \pi r^2.\nonumber \]

Find the area of a circle having a diameter of 12.5 meters. Use 3.14 for π and round the answer for the area to the nearest tenth of a square meter.

Solution

The diameter is twice the radius.

\[d = 2r\nonumber \]

Substitute 12.5 for d and solve for r.

\[ \begin{aligned} 12.5 = 2r ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Substitute 12.5 for } d.} \\ \frac{12.5}{2} = \frac{2r}{2} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Divide both sides by 2.}} \\ 6.25 = r ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Simplify.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Hence, the radius is 6.25 meters. To find the area, use the formula

\[A = \pi r^2\nonumber \]

and substitute: 3.14 for π and 6.25 for r.

\[ \begin{aligned} A = (3.14)(6.25)^2 ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Substitute: 3.14 for } \pi, \text{ 6.25 for } r.} \\ = (3.14)(39.0625) ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Square first: } (6.25)^2 = 39.0625} \\ =122.65625 ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply: } (3.14)(39.0625) = 122.65625} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

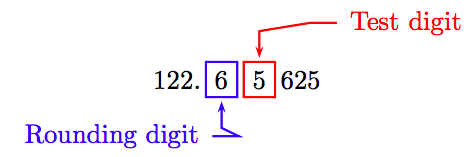

Hence, the approximate area of the circle is A = 122.65625 square meters. To round to the nearest tenth of a square meter, identify the rounding digit and the test digit.

Because the test digit is greater than or equal to 5, add 1 to the rounding digit and truncate. Thus, correct to the nearest tenth of a square meter, the area of the circle is approximately

\[A ≈ 122.7 \text{ m}^2.\nonumber \]

Find the area of a circle having radius 12.2 centimeters. Use π ≈ 3.14

- Answer

-

467.3576 cm2

Exercises

In Exercises 1-28, multiply the decimals.

1. (6.7)(0.03)

2. (2.4)(0.2)

3. (28.9)(5.9)

4. (33.5)(2.1)

5. (4.1)(4.6)

6. (2.6)(8.2)

7. (75.3)(0.4)

8. (21.4)(0.6)

9. (6.98)(0.9)

10. (2.11)(0.04)

11. (57.9)(3.29)

12. (3.58)(16.3)

13. (47.3)(0.9)

14. (30.7)(0.4)

15. (9.9)(6.7)

16. (7.2)(6.1)

17. (19.5)(7.9)

18. (43.4)(8.9)

19. (6.9)(0.3)

20. (7.7)(0.7)

21. (35.3)(3.81)

22. (5.44)(9.58)

23. (2.32)(0.03)

24. (4.48)(0.08)

25. (3.02)(6.7)

26. (1.26)(9.4)

27. (4.98)(6.2)

28. (3.53)(2.9)

In Exercises 29-56, multiply the decimals.

29. (−9.41)(0.07)

30. (4.45)(−0.4)

31. (−7.4)(−0.9)

32. (−6.9)(0.05)

33. (−8.2)(3.7)

34. (−7.5)(−6.6)

35. (9.72)(−9.1)

36. (6.22)(−9.4)

37. (−6.4)(2.6)

38. (2.3)(−4.4)

39. (−39.3)(−0.8)

40. (57.7)(−0.04)

41. (63.1)(−0.02)

42. (−51.1)(−0.8)

43. (−90.8)(3.1)

44. (−74.7)(2.9)

45. (47.5)(−82.1)

46. (−14.8)(−12.7)

47. (−31.1)(−4.8)

48. (−28.7)(−6.8)

49. (−2.5)(−0.07)

50. (−1.3)(−0.05)

51. (1.02)(−0.2)

52. (−7.48)(−0.1)

53. (7.81)(−5.5)

54. (−1.94)(4.2)

55. (−2.09)(37.9)

56. (20.6)(−15.2)

In Exercises 57-68, multiply the decimal by the given power of 10.

57. 24.264 · 10

58. 65.722 · 100

59. 53.867 · 104

60. 23.216 · 104

61. 5.096 · 103

62. 60.890 · 103

63. 37.968 · 103

64. 43.552 · 103

65. 61.303 · 100

66. 83.837 · 1000

67. 74.896 · 1000

68. 30.728 · 100

In Exercises 69-80, simplify the given expression.

69. (0.36)(7.4) − (−2.8)2

70. (−8.88)(−9.2) − (−2.3)2

71. 9.4 − (−7.7)(1.2)2

72. 0.7 − (−8.7)(−9.4)2

73. 5.94 − (−1.2)(−1.8)2

74. −2.6 − (−9.8)(9.9)2

75. 6.3 − 4.2(9.3)2

76. 9.9 − (−4.1)(8.5)2

77. (6.3)(1.88) − (−2.2)2

78. (−4.98)(−1.7) − 3.52

79. (−8.1)(9.4) − 1.82

80. (−3.63)(5.2) − 0.82

81. Given a = −6.24, b = 0.4, and c = 7.2, evaluate the expression a − bc2.

82. Given a = 4.1, b = −1.8, and c = −9.5, evaluate the expression a − bc2.

83. Given a = −2.4, b = −2.1, and c = −4.6, evaluate the expression ab − c2.

84. Given a = 3.3, b = 7.3, and c = 3.4, evaluate the expression ab − c2.

85. Given a = −3.21, b = 3.5, and c = 8.3, evaluate the expression a − bc2.

86. Given a = 7.45, b = −6.1, and c = −3.5, evaluate the expression a − bc2.

87. Given a = −4.5, b = −6.9, and c = 4.6, evaluate the expression ab − c2.

88. Given a = −8.3, b = 8.2, and c = 5.4, evaluate the expression ab − c2.

89. A circle has a diameter of 8.56 inches. Using π ≈ 3.14, find the circumference of the circle, correct to the nearest tenth of an inch.

90. A circle has a diameter of 14.23 inches. Using π ≈ 3.14, find the circumference of the circle, correct to the nearest tenth of an inch.

91. A circle has a diameter of 12.04 inches. Using π ≈ 3.14, find the circumference of the circle, correct to the nearest tenth of an inch.

92. A circle has a diameter of 14.11 inches. Using π ≈ 3.14, find the circumference of the circle, correct to the nearest tenth of an inch.

93. A circle has a diameter of 10.75 inches. Using π ≈ 3.14, find the area of the circle, correct to the nearest hundredth of a square inch.

94. A circle has a diameter of 15.49 inches. Using π ≈ 3.14, find the area of the circle, correct to the nearest hundredth of a square inch.

95. A circle has a diameter of 13.96 inches. Using π ≈ 3.14, find the area of the circle, correct to the nearest hundredth of a square inch.

96. A circle has a diameter of 15.95 inches. Using π ≈ 3.14, find the area of the circle, correct to the nearest hundredth of a square inch.

97. Sue has decided to build a circular fish pond near her patio. She wants it to be 15 feet in diameter and 1.5 feet deep. What is the volume of water it will hold? Use π ≈ 3.14. Hint: The volume of a cylinder is given by the formula V = πr2h, which is the area of the circular base times the height of the cylinder.

98. John has a decision to make regarding his employment. He currently has a job at Taco Loco in Fortuna. After taxes, he makes about $9.20 per hour and works about 168 hours a month. He currently pays $400 per month for rent. He has an opportunity to move to Santa Rosa and take a job at Mi Ultimo Refugio which would pay $10.30 per hour after taxes for 168 hours a month, but his rent would cost $570 per month.

a) After paying for housing in Fortuna, how much does he have left over each month for other expenditures?

b) After paying for housing in Santa Rosa, how much would he have left over each month for other expenditures?

c) For which job would he have more money left after paying rent and how much would it be?

99. John decided to move to Santa Rosa and take the job at Mi Ultimo Refugio (see Exercise 98). He was able to increase his income because he could work 4 Sundays a month at time-and-a half. So now he worked 32 hours a month at time-and-a-half and 136 hours at the regular rate of $10.30 (all after taxes were removed). Note: He previously had worked 168 hours per month at $10.30 per hour.

a) What was his new monthly income?

b) How much did his monthly income increase?

100. Electric Bill. On a recent bill, PGE charged $0.11531 per Kwh for the first 333 Kwh of electrical power used. If a household used 312 Kwh of power, what was their electrical bill?

101. Cabernet. In Napa Valley, one acre of good land can produce about 3.5 tons of quality grapes. At an average price of $3,414 per ton for premium cabernet, how much money could you generate on one acre of cabernet farming? Associated Press-Times-Standard 03/11/10 Grape moth threatens Napa Valley growing method.

102. Fertilizer. Using the 2008 Ohio Farm Custom Rates, the average cost for spreading dry bulk fertilizer is about $4.50 per acre. What is the cost to fertilize 50 acres?

103. Agribusiness. Huge corporate agribarns house 1000 pigs each.

a) If each pig weighs approximately 100 pounds, how many pounds of pig is in each warehouse?

b) At an average $1.29 per pound, what is the total cash value for a corporate agribarn? Associated Press-Times-Standard 12/29/09 Pressure rises to stop antibiotics in agriculture.

104. Shipwrecks. A dozen centuries-old shipwrecks were found in the Baltic Sea by a gas company building an underwater pipeline between Russia and Germany. The 12 wrecks were found in a 30-mile-long and 1.2-mile-wide corridor at a depth of 430 feet. Model the corridor with a rectangle and find the approximate area of the region where the ships were found. Associated Press-Times-Standard 03/10/10 Centuries-old shipwrecks found in Baltic Sea.

105. Radio dish. The diameter of the “workhorse fleet” of radio telescopes, like the one in Goldstone, California, is 230 feet. What is the circumference of the radio telescope dish to the nearest tenth? Associated Press-Times-Standard 03/09/2010 NASA will repair deep space antenna in California desert.

Answers

1. 0.201

3. 170.51

5. 18.86

7. 30.12

9. 6.282

11. 190.491

13. 42.57

15. 66.33

17. 154.05

19. 2.07

21. 134.493

23. 0.0696

25. 20.234

27. 30.876

29. −0.6587

31. 6.66

33. −30.34

35. −88.452

37. −16.64

39. 31.44

41. −1.262

43. −281.48

45. −3899.75

47. 149.28

49. 0.175

51. −0.204

53. −42.955

55. −79.211

57. 242.64

59. 538670

61. 5096

63. 37968

65. 6130.3

67. 74896

69. −5.176

71. 20.488

73. 9.828

75. −356.958

77. 7.004

79. −79.38

81. −26.976

83. −16.12

85. −244.325

87. 9.89

89. 26.9 in.

91. 37.8 in.

93. 90.72 square inches

95. 152.98 square inches

97. 264.9375 cubic feet

99.

a) $1895.20

b) $164.80

101. $11, 949

103.

a) 100, 000 pounds

b) $129,000

105. 722.2 feet