4.1: Visualize Fractions (Part 1)

- Page ID

- 4991

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Understand the meaning of fractions

- Model improper fractions and mixed numbers

- Convert between improper fractions and mixed numbers

- Model equivalent fractions

- Find equivalent fractions

- Locate fractions and mixed numbers on the number line

- Order fractions and mixed numbers

Before you get started, take this readiness quiz.

- Simplify: \(5 • 2 + 1\). If you missed this problem, review Example 2.1.8.

- Fill in the blank with \(<\) or \(>\): \(−2\)__\(−5\). If you missed this problem, review Example 3.1.2.

Understand the Meaning of Fractions

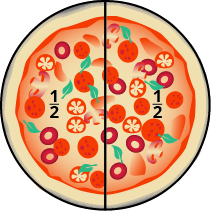

Andy and Bobby love pizza. On Monday night, they share a pizza equally. How much of the pizza does each one get? Are you thinking that each boy gets half of the pizza? That’s right. There is one whole pizza, evenly divided into two parts, so each boy gets one of the two equal parts. In math, we write \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) to mean one out of two parts.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)

On Tuesday, Andy and Bobby share a pizza with their parents, Fred and Christy, with each person getting an equal amount of the whole pizza. How much of the pizza does each person get? There is one whole pizza, divided evenly into four equal parts. Each person has one of the four equal parts, so each has \(\dfrac{1}{4}\) of the pizza.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)

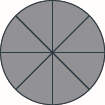

On Wednesday, the family invites some friends over for a pizza dinner. There are a total of \(12\) people. If they share the pizza equally, each person would get \(\dfrac{1}{12}\) of the pizza.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)

A fraction is written \(\dfrac{a}{b}\), where \(a\) and \(b\) are integers and \(b ≠ 0\). In a fraction, \(a\) is called the numerator and \(b\) is called the denominator.

A fraction is a way to represent parts of a whole. The denominator \(b\) represents the number of equal parts the whole has been divided into, and the numerator \(a\) represents how many parts are included. The denominator, \(b\), cannot equal zero because division by zero is undefined.

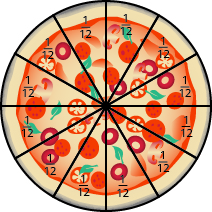

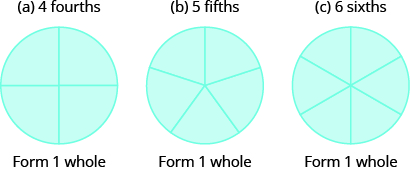

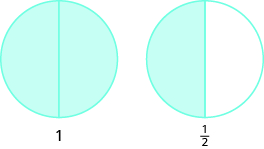

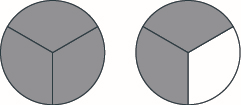

In Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\), the circle has been divided into three parts of equal size. Each part represents \(\dfrac{1}{3}\) of the circle. This type of model is called a fraction circle. Other shapes, such as rectangles, can also be used to model fractions.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)

What does the fraction \(\dfrac{2}{3}\) represent? The fraction \(\dfrac{2}{3}\) means two of three equal parts.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)

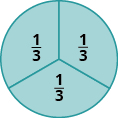

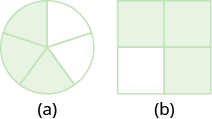

Name the fraction of the shape that is shaded in each of the figures.

Solution

We need to ask two questions. First, how many equal parts are there? This will be the denominator. Second, of these equal parts, how many are shaded? This will be the numerator.

| How many equal parts are there? | There are eight equal parts. |

| How many are shaded? | Five parts are shaded. |

Five out of eight parts are shaded. Therefore, the fraction of the circle that is shaded is \(\dfrac{5}{8}\).

| How many equal parts are there? | There are nineequal parts. |

| How many are shaded? | Two parts are shaded. |

Two out of nine parts are shaded. Therefore, the fraction of the square that is shaded is \(\dfrac{2}{9}\).

Name the fraction of the shape that is shaded in each figure:

- Answer a

-

\(\dfrac{3}{8}\)

- Answer b

-

\(\dfrac{4}{9}\)

Name the fraction of the shape that is shaded in each figure:

- Answer a

-

\(\dfrac{3}{5}\)

- Answer b

-

\(\dfrac{3}{4}\)

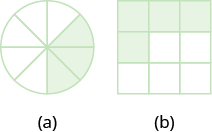

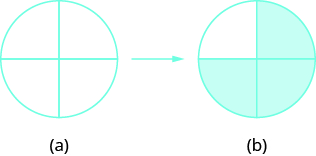

Shade \(\dfrac{3}{4}\) of the circle.

Solution

The denominator is \(4\), so we divide the circle into four equal parts (a). The numerator is \(3\), so we shade three of the four parts (b).

\(\dfrac{3}{4}\) of the circle is shaded.

Shade \(\dfrac{6}{8}\) of the circle.

- Answer

-

Shade \(\dfrac{2}{5}\) of the rectangle.

- Answer

-

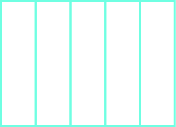

In Example \(\PageIndex{1}\) and Example \(\PageIndex{2}\), we used circles and rectangles to model fractions. Fractions can also be modeled as manipulatives called fraction tiles, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). Here, the whole is modeled as one long, undivided rectangular tile. Beneath it are tiles of equal length divided into different numbers of equally sized parts.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)

We’ll be using fraction tiles to discover some basic facts about fractions. Refer to Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) to answer the following questions:

| How many \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) tiles does it take to make one whole tile? | It takes two halves to make a whole, so two out of two is \(\dfrac{2}{2}\) = 1. |

| How many \(\dfrac{1}{3}\) tiles does it take to make one whole tile? | It takes three thirds, so three out of three is \(\dfrac{3}{3}\) = 1. |

| How many \(\dfrac{1}{4}\) tiles does it take to make one whole tile? | It takes four fourths, so four out of four is \(\dfrac{4}{4}\) = 1. |

| How many \(\dfrac{1}{5}\) tiles does it take to make one whole tile? | It takes six sixths, so six out of six is \(\dfrac{6}{6}\) = 1. |

| What if the whole were divided into 24 equal parts? (We have not shown fraction tiles to represent this, but try to visualize it in your mind.) How many \(\dfrac{1}{24}\) tiles does it take to make one whole tile? | It takes 24 twenty-fourths, so \(\dfrac{24}{24}\) = 1. |

It takes \(24\) twenty-fourths, so \(\dfrac{24}{24} = 1\). This leads us to the Property of One.

Any number, except zero, divided by itself is one.

\[\dfrac{a}{a} = 1 \qquad \qquad (a \neq 0)\]

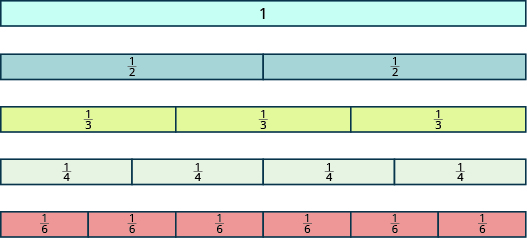

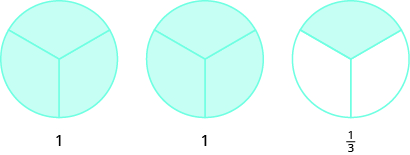

Use fraction circles to make wholes using the following pieces:

- \(4\) fourths

- \(5\) fifths

- \(6\) sixths

Solution

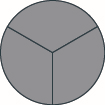

Use fraction circles to make wholes with the following pieces: \(3\) thirds.

- Answer

-

Use fraction circles to make wholes with the following pieces: \(8\) eighths.

- Answer

-

What if we have more fraction pieces than we need for \(1\) whole? We’ll look at this in the next example.

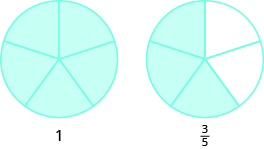

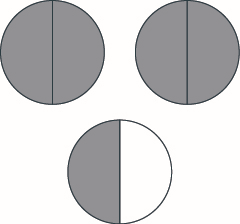

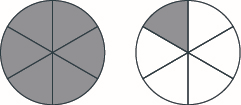

Use fraction circles to make wholes using the following pieces:

- \(3\) halves

- \(8\) fifths

- \(7\) thirds

Solution

- \(3\) halves make \(1\) whole with \(1\) half left over.

- \(8\) fifths make \(1\) whole with \(3\) fifths left over.

- \(7\) thirds make \(2\) wholes with \(1\) third left over.

Use fraction circles to make wholes with the following pieces: \(5\) thirds.

- Answer

-

Use fraction circles to make wholes with the following pieces: \(5\) halves.

- Answer

-

Model Improper Fractions and Mixed Numbers

In Example \(\PageIndex{4b}\), you had eight equal fifth pieces. You used five of them to make one whole, and you had three fifths left over. Let us use fraction notation to show what happened. You had eight pieces, each of them one fifth, \(\dfrac{1}{5}\), so altogether you had eight fifths, which we can write as \(\dfrac{8}{5}\). The fraction \(\dfrac{8}{5}\) is one whole, \(1\), plus three fifths, \(\dfrac{3}{5}\), or \(1 \dfrac{3}{5}\), which is read as one and three-fifths.

The number \(1 \dfrac{3}{5}\) is called a mixed number. A mixed number consists of a whole number and a fraction.

A mixed number consists of a whole number \(a\) and a fraction \(\dfrac{b}{c}\) where \(c ≠ 0\). It is written as follows.

\[a \dfrac{b}{c} \qquad \qquad c \neq 0\]

Fractions such as \(\dfrac{5}{4}\), \(\dfrac{3}{2}\), \(\dfrac{5}{5}\), and \(\dfrac{7}{3}\) are called improper fractions. In an improper fraction, the numerator is greater than or equal to the denominator, so its value is greater than or equal to one. When a fraction has a numerator that is smaller than the denominator, it is called a proper fraction, and its value is less than one. Fractions such as \(\dfrac{1}{2}\), \(\dfrac{3}{7}\), and \(\dfrac{11}{18}\) are proper fractions.

The fraction \(\dfrac{a}{b}\) is a proper fraction if \(a < b\) and an improper fraction if \(a ≥ b\).

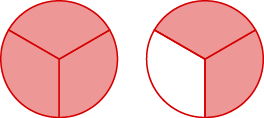

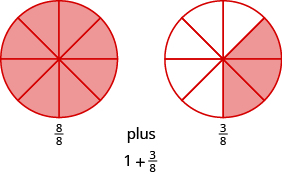

Name the improper fraction modeled. Then write the improper fraction as a mixed number.

Solution

Each circle is divided into three pieces, so each piece is \(\dfrac{1}{3}\) of the circle. There are four pieces shaded, so there are four thirds or \(\dfrac{4}{3}\). The figure shows that we also have one whole circle and one third, which is \(1 \dfrac{1}{3}\). So, \(\dfrac{4}{3} = 1 \dfrac{1}{3}\).

Name the improper fraction. Then write it as a mixed number.

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{5}{3}=1\dfrac{2}{3}\)

Name the improper fraction. Then write it as a mixed number.

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{13}{8}=1\dfrac{5}{8}\)

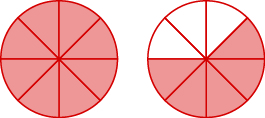

Draw a figure to model \(\dfrac{11}{8}\).

Solution

The denominator of the improper fraction is \(8\). Draw a circle divided into eight pieces and shade all of them. This takes care of eight eighths, but we have \(11\) eighths. We must shade three of the eight parts of another circle.

So, \(\dfrac{11}{8} = 1 \dfrac{3}{8}\).

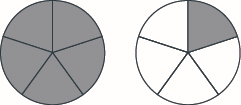

Draw a figure to model \(\dfrac{7}{6}\).

- Answer

-

Draw a figure to model \(\dfrac{6}{5}\).

- Answer

-

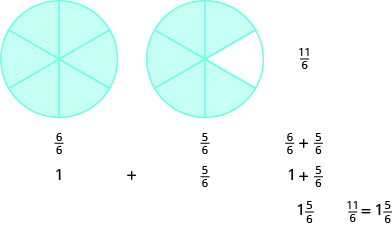

Use a model to rewrite the improper fraction \(\dfrac{11}{6}\) as a mixed number.

Solution

We start with \(11\) sixths \(\left(\dfrac{11}{6}\right)\). We know that six sixths makes one whole.

\[\dfrac{6}{6} = 1 \nonumber \]

That leaves us with five more sixths, which is \(\dfrac{5}{6}\) (11 sixths minus 6 sixths is 5 sixths). So, \(\dfrac{11}{6} = 1 \dfrac{5}{6}\).

Use a model to rewrite the improper fraction as a mixed number: \(\dfrac{9}{7}\).

- Answer

-

\(1\dfrac{2}{7}\)

Use a model to rewrite the improper fraction as a mixed number: \(\dfrac{7}{4}\).

- Answer

-

\(1\dfrac{3}{4}\)

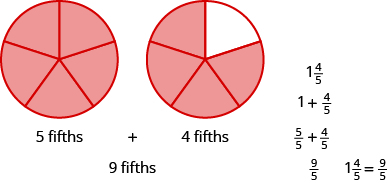

Use a model to rewrite the mixed number \(1 \dfrac{4}{5}\) as an improper fraction.

Solution

The mixed number \(1 \dfrac{4}{5}\) means one whole plus four fifths. The denominator is \(5\), so the whole is \(\dfrac{5}{5}\). Together five fifths and four fifths equals nine fifths. So, \(1 \dfrac{4}{5} = \dfrac{9}{5}\).

Use a model to rewrite the mixed number as an improper fraction: \(1 \dfrac{3}{8}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{11}{8}\)

Use a model to rewrite the mixed number as an improper fraction: \(1 \dfrac{5}{6}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{11}{6}\)

Convert between Improper Fractions and Mixed Numbers

In Example \(\PageIndex{7}\), we converted the improper fraction \(\dfrac{11}{6}\) to the mixed number \(1 \dfrac{5}{6}\) using fraction circles. We did this by grouping six sixths together to make a whole; then we looked to see how many of the \(11\) pieces were left. We saw that \(\dfrac{11}{6}\) made one whole group of six sixths plus five more sixths, showing that \(\dfrac{11}{6} = \dfrac{15}{6}\).

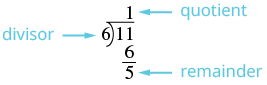

The division expression \(\dfrac{11}{6}\) (which can also be written as \(6 \overline{\smash{)}11}\)) tells us to find how many groups of \(6\) are in \(11\). To convert an improper fraction to a mixed number without fraction circles, we divide.

Convert \(\dfrac{11}{6}\) to a mixed number.

Solution

| Divide the denominator into the numerator. | Remember \(\dfrac{11}{6}\) means 11 ÷ 6. |

| Identify the quotient, remainder and divisor. |  |

| Write the mixed number as \(quotient \dfrac{remainder}{divisor}\). | \(1 \dfrac{5}{6}\) |

So, \(\dfrac{11}{6} = 1 \dfrac{5}{6}\).

Convert the improper fraction to a mixed number: \(\dfrac{13}{7}\).

- Answer

-

\(1\dfrac{6}{7}\)

Convert the improper fraction to a mixed number: \(\dfrac{14}{9}\).

- Answer

-

\(1\dfrac{5}{9}\)

Step 1. Divide the denominator into the numerator.

Step 2. Identify the quotient, remainder, and divisor.

Step 3. Write the mixed number as \(quotient \dfrac{remainder}{divisor}\).

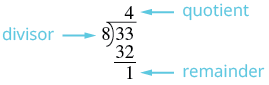

Convert the improper fraction \(\dfrac{33}{8}\) to a mixed number.

Solution

| Divide the denominator into the numerator. | Remember, \(\dfrac{33}{8}\) means \(8 \overline{\smash{)}33}\). |

| Identify the quotient, remainder, and divisor. |  |

| Write the mixed number as \(quotient \dfrac{remainder}{divisor}\). | \(4 \dfrac{1}{8}\) |

So, \(\dfrac{33}{8} = 4 \dfrac{1}{8}\).

Convert the improper fraction to a mixed number: \(\dfrac{23}{7}\).

- Answer

-

\(3\dfrac{2}{7}\)

Convert the improper fraction to a mixed number: \(\dfrac{48}{11}\).

- Answer

-

\(4\dfrac{4}{11}\)

In Example \(\PageIndex{8}\), we changed \(1 \dfrac{4}{5}\) to an improper fraction by first seeing that the whole is a set of five fifths. So we had five fifths and four more fifths.

\[\dfrac{5}{5} + \dfrac{4}{5} = \dfrac{9}{5} \nonumber \]

Where did the nine come from? There are nine fifths—one whole (five fifths) plus four fifths. Let us use this idea to see how to convert a mixed number to an improper fraction.

Convert the mixed number \(4 \dfrac{2}{3}\) to an improper fraction.

| Multiply the whole number by the denominator. | \(4 \dfrac{2}{3}\) |

| The whole number is 4 and the denominator is 3. |  |

| Simplify. |  |

| Add the numerator to the product. | |

| The numerator of the mixed number is 2. |  |

| Simplify. |  |

| Write the final sum over the original denominator. | |

| The denominator is 3. | \(\dfrac{14}{3}\) |

Convert the mixed number to an improper fraction: \(3 \dfrac{5}{7}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{26}{7}\)

Convert the mixed number to an improper fraction: \(2 \dfrac{7}{8}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{23}{8}\)

Step 1. Multiply the whole number by the denominator.

Step 2. Add the numerator to the product found in Step 1.

Step 3. Write the final sum over the original denominator.

Convert the mixed number \(10 \dfrac{2}{7}\) to an improper fraction.

| Multiply the whole number by the denominator. | \(10 \dfrac{2}{7}\) |

| The whole number is 10 and the denominator is 7. |  |

| Simplify. |  |

| Add the numerator to the product. | |

| The numerator of the mixed number is 2. |  |

| Simplify. |  |

| Write the final sum over the original denominator. | |

| The denominator is 7. | \(\dfrac{72}{7}\) |

Convert the mixed number to an improper fraction: \(4 \dfrac{6}{11}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{50}{11}\)

Convert the mixed number to an improper fraction: \(11 \dfrac{1}{3}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{34}{3}\)

Contributors and Attributions

Lynn Marecek (Santa Ana College) and MaryAnne Anthony-Smith (Formerly of Santa Ana College). This content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License v4.0 "Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/fd53eae1-fa2...49835c3c@5.191."