7.1: Solving Trigonometric Equations with Identities

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

In the last chapter, we solved basic trigonometric equations. In this section, we explore the techniques needed to solve more complicated trig equations. Building from what we already know makes this a much easier task.

Consider the function

Similarly, for

Using these same concepts, we consider the composition of these two functions:

This creates an equation that is a polynomial trig function. With these types of functions, we use algebraic techniques like factoring and the quadratic formula, along with trigonometric identities and techniques, to solve equations.

As a reminder, here are some of the essential trigonometric identities that we have learned so far:

DefinitionS: IDENTITIES

Pythagorean Identities

Negative Angle Identities

Reciprocal Identities

Example

Solve

Solution

This equation kind of looks like a quadratic equation, but with sin(t) in place of an algebraic variable (we often call such an equation “quadratic in sine”). As with all quadratic equations, we can use factoring techniques or the quadratic formula. This expression factors nicely, so we proceed by factoring out the common factor of sin(

Using the zero product theorem, we know that the product on the left will equal zero if either factor is zero, allowing us to break this equation into two cases:

We can solve each of these equations independently, using our knowledge of special angles.

Together, this gives us four solutions to the equation on

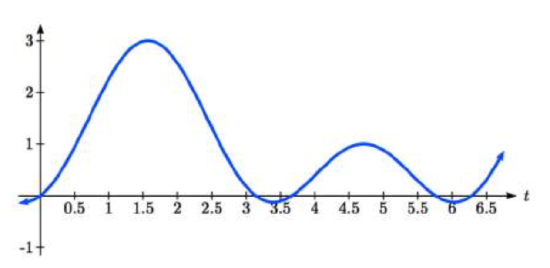

We could check these answers are reasonable by graphing the function and comparing the zeros.

Example

Solve

Solution

Since the left side of this equation is quadratic in secant, we can try to factor it, and hope it factors nicely.

If it is easier to for you to consider factoring without the trig function present, consider using a substitution

Undoing the substitution,

Since we have a product equal to zero, we break it into the two cases and solve each separately.

Since the cosine has a range of [-1, 1], the cosine will never take on an output of -3. There are no solutions to this case.

Continuing with the second case,

These are the only two solutions on the interval.

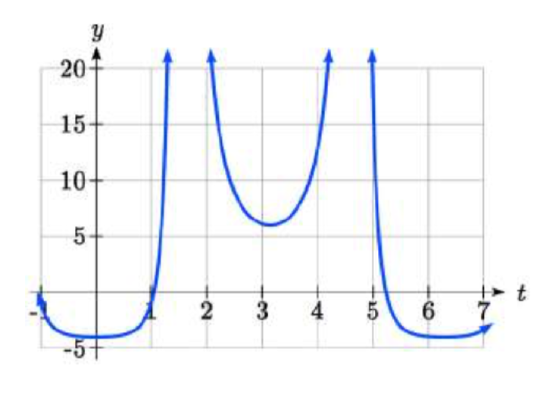

By utilizing technology to graph

Exercise

Solve

- Answer

-

Factor as

When solving some trigonometric equations, it becomes necessary to first rewrite the equation using trigonometric identities. One of the most common is the Pythagorean Identity,

IDENTITIES

Alternate Forms of the Pythagorean Identity

These identities become very useful whenever an equation involves a combination of sine and cosine functions.

Example

Solve

Solution

Since this equation has a mix of sine and cosine functions, it becomes more complicated to solve. It is usually easier to work with an equation involving only one trig function. This is where we can use the Pythagorean Identity.

Since this is now quadratic in cosine, we rearrange the equation so one side is zero and factor.

This product will be zero if either factor is zero, so we can break this into two separate cases and solve each independently.

Exercise

Solve

- Answer

-

In addition to the Pythagorean Identity, it is often necessary to rewrite the tangent, secant, cosecant, and cotangent as part of solving an equation.

Example

Solve

Solution

With a combination of tangent and sine, we might try rewriting tangent

At this point, you may be tempted to divide both sides of the equation by sin(

Resist the urge. When we divide both sides of an equation by a quantity, we are assuming the quantity is never zero. In this case, when sin(

To avoid this problem, we can rearrange the equation so that one side is zero (You technically can divide by sin(x), as long as you separately consider the case where sin(x) = 0. Since it is easy to forget this step, the factoring approach used in the example is recommended.).

From here, we can see we get solutions when

Using our knowledge of the special angles of the unit circle,

For the second equation, we will need the inverse cosine.

We have four solutions on

Example

Solve

- Answer

-

Example

Solve

Solution

This does not appear to factor nicely so we use the quadratic formula, remembering that we are solving for cos(

Using the negative square root first,

This has no solutions, since the cosine can’t be less than -1.

Using the positive square root,

Important Topics of This Section

- Review of Trig Identities

- Solving Trig Equations

- By Factoring

- Using the Quadratic Formula

- Utilizing Trig Identities to simplify