4.5: Graphs of Logarithmic Functions

- Page ID

- 13854

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Recall that the exponential function \(f(x)=2^{x}\) produces this table of values

| \(x\) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| \(f(x)\) | \(\dfrac{1}{8}\) | \(\dfrac{1}{4}\) | \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

Since the logarithmic function is an inverse of the exponential, \(g(x)=\log _{2} (x)\) produces the table of values

| \(x\) | \(\dfrac{1}{8}\) | \(\dfrac{1}{4}\) | \(\dfrac{1}{2}\) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| \(g(x)\) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

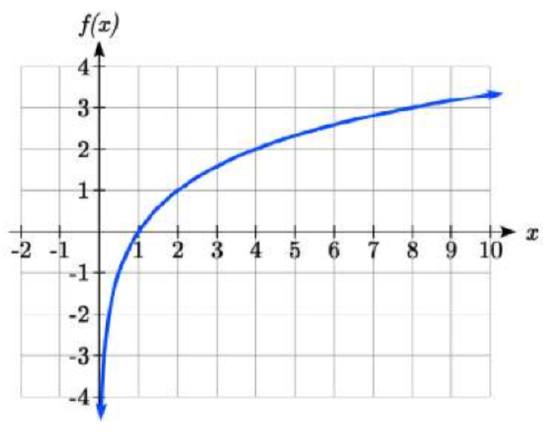

In this second table, notice that

1. As the input increases, the output increases.

2. As input increases, the output increases more slowly.

3. Since the exponential function only outputs positive values, the logarithm can only accept positive values as inputs, so the domain of the log function is \((0,\infty )\).

4. Since the exponential function can accept all real numbers as inputs, the logarithm can output any real number, so the range is all real numbers or \((-\infty ,\infty )\).

Sketching the graph, notice that as the input approaches zero from the right, the output of the function grows very large in the negative direction, indicating a vertical asymptote at \(x = 0\).

In symbolic notation we write as \(x \to 0^{+} ,f(x) \to -\infty\), and as\(x \to \infty ,f(x) \to \infty\)

Graphical Features of the Logarithm

- Graphically, in the function \(g(x)=\log _{b} (x)\)

- The graph has a horizontal intercept at (1, 0)

- The graph has a vertical asymptote at \(x = 0\)

- The graph is increasing and concave down

- The domain of the function is \(x > 0\), or \((0,\infty )\)

- The range of the function is all real numbers, or \((-\infty ,\infty )\)

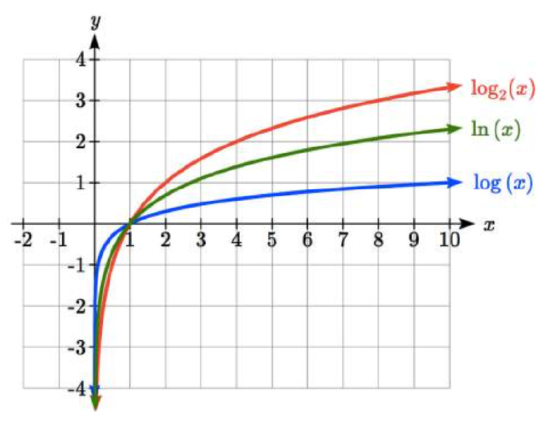

When sketching a general logarithm with base \(b\), it can be helpful to remember that the graph will pass through the points (1, 0) and (\(b\), 1). To get a feeling for how the base affects the shape of the graph, examine the graphs below.

Notice that the larger the base, the slower the graph grows. For example, the common log graph, while it grows without bound, it does so very slowly. For example, to reach an output of 8, the input must be 100,000,000.

Another important observation made was the domain of the logarithm. Like the reciprocal and square root functions, the logarithm has a restricted domain which must be considered when finding the domain of a composition involving a log.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Find the domain of the function \(f(x)=\log (5-2x)\).

Solution

The logarithm is only defined with the input is positive, so this function will only be defined when \(5 - 2x > 0\). Solving this inequality,

\[\begin{align*} -2x &>-5 \\[4pt] x &< \dfrac{5}{2} \end{align*} \nonumber\]

The domain of this function is \(x < \dfrac{5}{2}\), or in interval notation, \(\left(-\infty ,\dfrac{5}{2} \right)\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Find the domain of the function \(f(x)=\log (x-5)+2\); before solving this as an inequality, consider how the function has been transformed.

- Answer

-

Domain: {\(x\) | \(x > 5\)}

Transformations of the Logarithmic Function

Transformations can be applied to a logarithmic function using the basic transformation techniques, but as with exponential functions, several transformations result in interesting relationships.

First recall the change of base property tells us that:

\[\log _{b} x=\dfrac{\log _{c} x}{\log _{c} b} =\dfrac{1}{\log _{c} b} \log _{c} x \nonumber\]

From this, we can see that \(\log _{b} x\) is a vertical stretch or compression of the graph of the \(\log _{c} x\) graph. This tells us that a vertical stretch or compression is equivalent to a change of base. For this reason, we typically represent all graphs of logarithmic functions in terms of the common or natural log functions.

Next, consider the effect of a horizontal compression on the graph of a logarithmic function. Considering \(f(x)=\log (cx)\), we can use the sum property to see

\[ \begin{align*} f(x) &=\log (cx) \\[4pt] &=\log (c)+\log (x) \end{align*}\]

Since log(\(c\)) is a constant, the effect of a horizontal compression is the same as the effect of a vertical shift.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

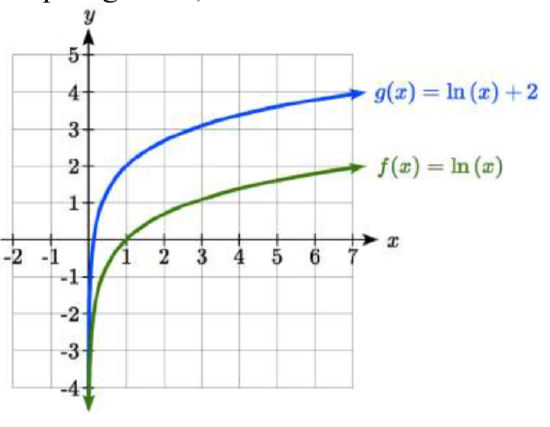

Sketch \(f(x)=\ln (x)\) and \(g(x)=\ln (x)+2\).

Solution

Graphing these,

Note that this vertical shift could also be written as a horizontal compression, since \(g(x)=\ln (x)+2=\ln (x)+\ln (e^{2} )=\ln (e^{2} x).\)

While a horizontal stretch or compression can be written as a vertical shift, a horizontal reflection is unique and separate from vertical shifting.

Finally, we will consider the effect of a horizontal shift on the graph of a logarithm.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

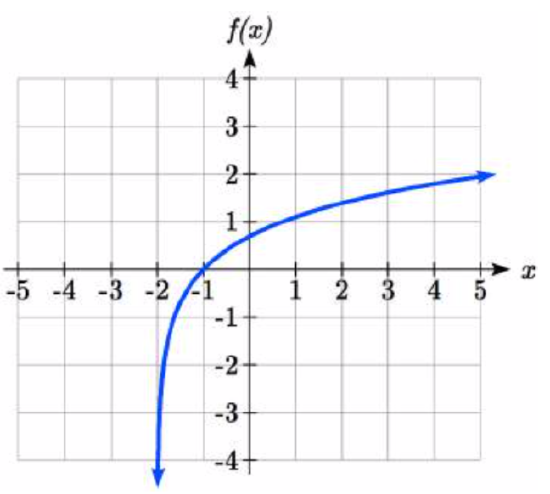

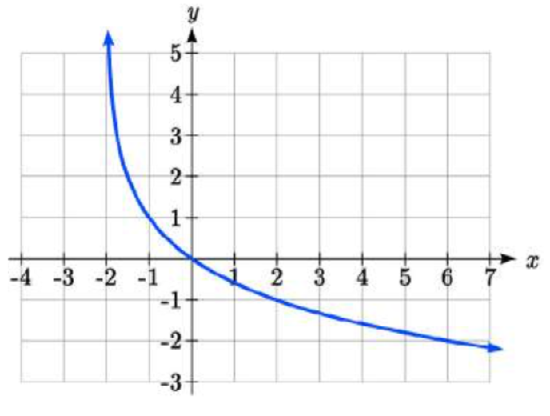

Sketch a graph of \(f(x)=\ln (x+2)\).

Solution

This is a horizontal shift to the left by 2 units. Notice that none of our logarithm rules allow us rewrite this in another form, so the effect of this transformation is unique. Shifting the graph,

Notice that due to the horizontal shift, the vertical asymptote shifted to \(x = -2\), and the domain shifted to \((-2,\infty )\).

Combining these transformations,

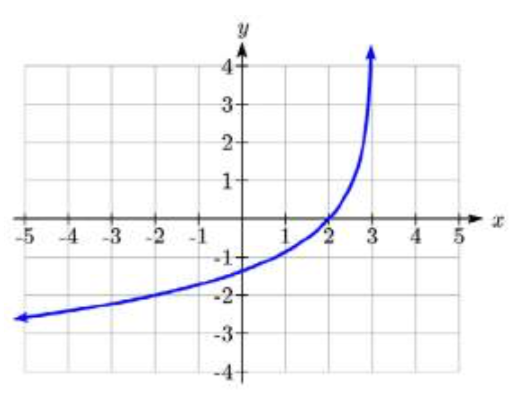

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Sketch a graph of \(f(x) = 5\log(-x + 2)\).

Solution

Factoring the inside as \(f (x) = 5\log(−(x − 2))\) reveals that this graph is that of the common logarithm, horizontally reflected, vertically stretched by a factor of 5, and shifted to the right by 2 units.

The vertical asymptote will be shifted to \(x = 2\) and the graph will have domain \((\infty, 2)\). A rough sketch can be created by using the vertical asymptote along with a couple points on the graph, such as

\[ \begin{align*} (f (1) &= 5\log(−1+ 2) = 5\log(1) = 0 \\[4pt] f (−8) &= 5\log(−(−8) + 2) = 5\log(10) = 5 \end{align*}\]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Sketch a graph of the function \(f(x)=-3\log (x-2)+1\).

- Answer

-

transormations of logs

Any transformed logarithmic function can be written in the form

\[f(x)=a\log (x-b)+k\text{ ,or }f(x)=a\log \left(-\left(x-b\right)\right)+k\] if horizontally reflected,

where \(x = b\) is the vertical asymptote.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

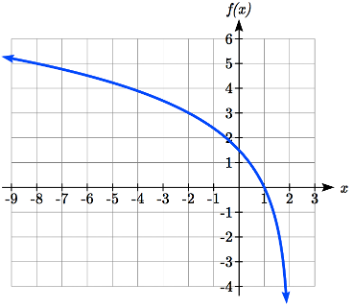

Find an equation for the logarithmic function graphed.

Solution

This graph has a vertical asymptote at \(x = –2\) and has been vertically reflected. We do not know yet the vertical shift (equivalent to horizontal stretch) or the vertical stretch (equivalent to a change of base). We know so far that the equation will have form

\[f(x)=-a\log (x+2)+k\nonumber\]

It appears the graph passes through the points (–1, 1) and (2, –1). Substituting in (–1, 1),

\[\begin{array}{l} {1=-a\log (-1+2)+k} \\ {1=-a\log (1)+k} \\ {1=k} \end{array}\nonumber\]

Next, substituting in (2, –1),

\[\begin{array}{l} {-1=-a\log (2+2)+1} \\ {-2=-a\log (4)} \\ {a=\dfrac{2}{\log (4)} } \end{array}\nonumber\]

This gives us the equation

\[f(x)=-\dfrac{2}{\log (4)} \log (x+2)+1. \nonumber\]

This could also be written as

\[f(x)=-2\log _{4} (x+2)+1. \nonumber\]

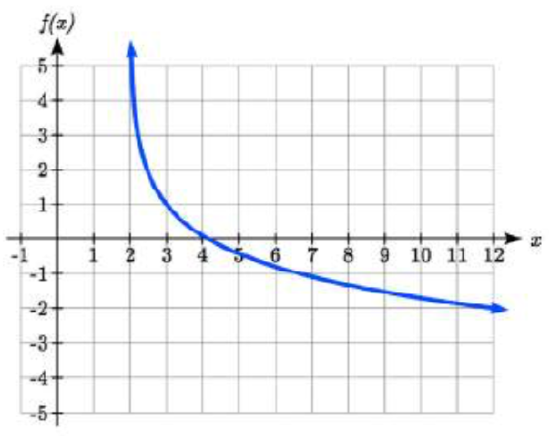

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Write an equation for the function graphed here.

- Answer

-

The graph is horizontally reflected and has a vertical asymptote at \(x = 3\), giving form \(f(x)=a\log \left(-\left(x-3\right)\right)+k\). Substituting in the point (2,0) gives \(0=a\log \left(-\left(2-3\right)\right)+k\), simplifying to \(k = 0\). Substituting in (-2,-2), \[-2=a\log \left(-\left(-2-3\right)\right)\nonumber\] so \[\dfrac{-2}{\log (5)} =a\nonumber\]The equation is \[f(x)=\dfrac{-2}{\log (5)} \log \left(-\left(x-3\right)\right)\nonumber\] or \[f(x)=-2\log _{5} \left(-\left(x-3\right)\right)\nonumber\]

flashback

Write the domain and range of the function graphed in Example 5, and describe its long run behavior.

- Answer

-

Domain: {\(x\) | \(x\) > -2}, Range: all real numbers; As \(x\to -2^{+} ,f(x)\to \infty\)and as \(x\to \infty ,f(x)\to -\infty\).

Important Topics of this Section

- Graph of the logarithmic function (domain and range)

- Transformation of logarithmic functions

- Creating graphs from equations

- Creating equations from graphs