3.8: Inverse Functions

- Page ID

- 33059

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Skills to Develop

- Verify inverse functions.

- Determine the domain and range of an inverse function, and restrict the domain of a function to make it one-to-one.

- Find or evaluate the inverse of a function.

- Use the graph of a one-to-one function to graph its inverse function on the same axes.

A reversible heat pump is a climate-control system that is an air conditioner and a heater in a single device. Operated in one direction, it pumps heat out of a house to provide cooling. Operating in reverse, it pumps heat into the building from the outside, even in cool weather, to provide heating. As a heater, a heat pump is several times more efficient than conventional electrical resistance heating.

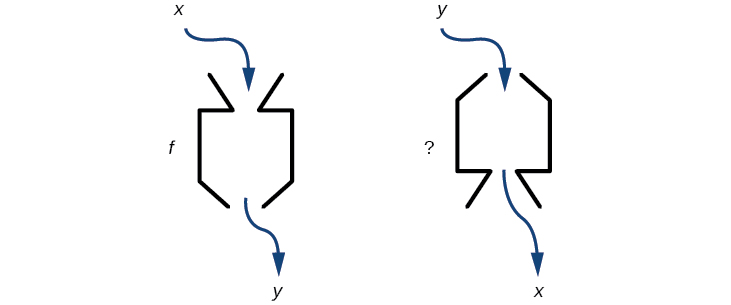

If some physical machines can run in two directions, we might ask whether some of the function “machines” we have been studying can also run backwards. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) provides a visual representation of this question. In this section, we will consider the reverse nature of functions.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Can a function “machine” operate in reverse?

Verifying That Two Functions Are Inverse Functions

Suppose a fashion designer traveling to Milan for a fashion show wants to know what the temperature will be. He is not familiar with the Celsius scale. To get an idea of how temperature measurements are related, he asks his assistant, Betty, to convert 75 degrees Fahrenheit to degrees Celsius. She finds the formula

\[C=\dfrac{5}{9}(F−32) \nonumber\]

and substitutes 75 for \(F\) to calculate

\[\dfrac{5}{9}(75−32)\approx24^{\circ} \nonumber\]

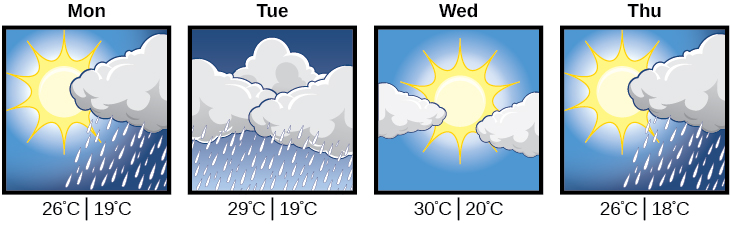

Knowing that a comfortable 75 degrees Fahrenheit is about 24 degrees Celsius, he sends his assistant the week’s weather forecast from Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) for Milan, and asks her to convert all of the temperatures to degrees Fahrenheit.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): A forecast of Monday’s through Thursday’s weather.

At first, Betty considers using the formula she has already found to complete the conversions. After all, she knows her algebra, and can easily solve the equation for \(F\) after substituting a value for \(C\). For example, to convert 26 degrees Celsius, she could write

\[\begin{align} 26&=\dfrac{5}{9}(F-32) \nonumber \\ 26⋅\dfrac{9}{5}&=F−32 \nonumber \\ F&=26⋅\dfrac{9}{5}+32\approx79^{\circ} \nonumber\end{align} \nonumber\]

After considering this option for a moment, however, she realizes that solving the equation for each of the temperatures will be awfully tedious. She realizes that since evaluation is easier than solving, it would be much more convenient to have a different formula, one that takes the Celsius temperature and outputs the Fahrenheit temperature.

The formula for which Betty is searching corresponds to the idea of an inverse function, a function for which the input of the original function becomes the output of the inverse function and the output of the original function becomes the input of the inverse function.

Given a function \(f(x)\), we represent its inverse as \(f^{−1}(x)\), read as “\(f\) inverse of \(x\).” The raised \(−1\) is part of the notation. It is not an exponent; it does not imply a power of \(−1\). In other words, \(f^{−1}(x)\) does not mean \(\frac{1}{f(x)}\) because \(\frac{1}{f(x)}\) is the reciprocal (or multiplicative inverse) of \(f\) and not the function inverse.

The “exponent-like” notation comes from an analogy between function composition and multiplication: just as \(a^{−1}a=1\) (1 is the identity element for multiplication) for any nonzero number \(a\), so \(f^{−1}{\circ}f\) equals the identity function; that is, if \(y=f(x)\), then

\[(f^{−1}{\circ}f)(x)=f^{−1}(f(x))=f^{−1}(y)=x. \nonumber\]

This holds for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f\). Informally, this means that an inverse function “undoes” the original function. However, just as zero does not have a reciprocal, some functions do not have inverses, as we will see later in this section.

For example, \(y=4x\) and \(y=\frac{1}{4}x\) are inverse functions.

\[(f^{−1}{\circ}f)(x)=f^{-1}(4x)=\dfrac{1}{4}(4x)=x \nonumber\]

and

\[(f{\circ}f^{−1})(x)=f\Big(\dfrac{1}{4}x\Big)=4\Big(\dfrac{1}{4}x\Big)=x \nonumber\]

A few coordinate pairs from the graph of the function \(y=4x\) are \((−2, −8)\), \((0, 0)\), and \((2, 8)\). A few coordinate pairs from the graph of the function \(y=\frac{1}{4}x\) are \((−8, −2)\), \((0, 0)\), and \((8, 2)\). If we interchange the input and output of each coordinate pair of a function, the interchanged coordinate pairs would appear on the graph of the inverse function.

Definition: Inverse Function

For any one-to-one function \(f(x)=y\), a function \(f^{−1}(x)\) is an inverse function of \(f\) if \(f^{−1}(y)=x\). This can also be written as \(f^{−1}(f(x))=x\) for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f\). It also follows that \(f(f^{−1}(x))=x\) for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f^{−1}\) .

Note that if a function \(f\) has an inverse \(f^{-1}\), then the inverse of \(f^{-1}\) is the function \(f\).

The notation \(f^{−1}\) is read “\(f\) inverse.” Like any other function, we can use any variable name as the input for \(f^{−1}\), so we will often write \(f^{−1}(x)\), which we read as “\(f\) inverse of \(x\).” Keep in mind that

\[f^{−1}(x)\neq\dfrac{1}{f(x)} \nonumber\]

and not all functions have inverses.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Identifying Inverse Function Values for a Given Input-Output Pair

If for a particular one-to-one function \(f(2)=4\) and \(f(5)=12\), what are the corresponding input and output values for the inverse function?

Solution

The inverse function reverses the input and output quantities, so if

\[f(2)=4, \text{ then } f^{-1}(4)=2 ;\\ f(5)=12, \text{ then }f^{-1}(12)=5 \nonumber\].

Alternatively, if we name the inverse function \(g\), then \(g(4)=2\) and \(g(12)=5\).

Analysis

Notice that if we show the coordinate pairs in a table form, the input and output are clearly reversed. See Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)

| \((x,f(x))\) | \((x,g(x))\) |

|---|---|

| \((2,4)\) | \((4,2)\) |

| \((5,12)\) | \((12,5)\) |

![]() \(\PageIndex{1}\)

\(\PageIndex{1}\)

Given that \(h^{-1}(6)=2\), what are the corresponding input and output values of the original function \(h\)?

- Answer

-

\(h(2)=6\)

![]() Given two functions \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\), test whether the functions are inverses of each other

Given two functions \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\), test whether the functions are inverses of each other

- Determine whether \(f(g(x))=x\).

- Determine whether \(g(f(x))=x\).

- If both statements are true, then \(g=f^{-1}\) and \(f=g^{-1}\). If either statement is false, then both are false, and \(g \neq f^{-1}\) and \(f \neq g^{-1}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Testing Inverse Relationships Algebraically

If \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x+2}\) and \(g(x)=\frac{1}{x}−2\), is \(g=f^{-1}\)?

Solution

\[\begin{align} g(f(x))&=\dfrac{1}{\frac{1}{x+2}}−2 \nonumber \\ &=x+2−2 \nonumber \\&=x \nonumber \end{align} \nonumber \]

so

\[g=f^{-1} \text{ and } f=g^{-1} \nonumber\]

This is enough to answer yes to the question, but we can also verify the other formula.

\[\begin{align} f(g(x))&=\dfrac{1}{\frac{1}{x}-2+2} \nonumber \\[5pt] &= \dfrac{1}{\frac{1}{x}} \nonumber \\ &=x \nonumber \end{align} \nonumber\]

Analysis

Notice the inverse operations are in reverse order of the operations from the original function.

![]() \(\PageIndex{2}\)

\(\PageIndex{2}\)

If \(f(x)=x^3−4\) and \(g(x)=\sqrt[3]{x+4}\), is \(g=f^{-1}\)?

- Answer

-

Yes

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Determining Inverse Relationships for Power Functions

If \(f(x)=x^3\) (the cube function) and \(g(x)=\frac{1}{3}x\), is \(g=f^{-1}\)?

Solution

\[f(g(x))=\left(\dfrac{1}{3}x\right)^3=\dfrac{1}{27}x^3\neq x \nonumber\]

No, the functions are not inverses.

Analysis

The correct inverse to the cube is, of course, the cube root \(\sqrt[3]{x}=x^{\frac{1}{3}}\); that is, the one-third is an exponent, not a multiplier.

![]() \(\PageIndex{3}\)

\(\PageIndex{3}\)

If \(f(x)=(x−1)^3\) and \(g(x)=\sqrt[3]{x}+1\), is \(g=f^{-1}\)?

- Answer

-

Yes

Finding Domain and Range of Inverse Functions

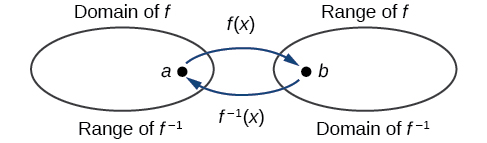

The outputs of the function \(f\) are the inputs to \(f^{-1}\), so the range of \(f\) is the domain of \(f^{-1}\). Likewise, because the outputs of \(f^{-1}\) are the inputs to \(f\), the domain of \(f\) is the range of \(f^{-1}\). We can visualize the situation as in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Domain and range of a function and its inverse.

However, not every function has an inverse. Consider the toolkit quadratic function \(f(x)=x^2\). If we want to construct an inverse to this function, the "wannabe" function is \(g(x) = \sqrt{x}\). However, we run into a problem, because for every given output of the quadratic function, there are two corresponding inputs (except when the input is 0). For example, the output 9 from the quadratic function corresponds to the inputs 3 and –3. But an output from a function is an input to its inverse; if this inverse input corresponds to more than one inverse output (input of the original function), then the “inverse” is not a function at all! To put it differently, the quadratic function is not a one-to-one function; it fails the horizontal line test, so it cannot have an inverse function. In order for a function to have an inverse, it must be a one-to-one function.

If a function is not one-to-one, it is possible to restrict the function to a part of its domain on which it is one-to-one. For example, we can make a restricted version of the square function \(f(x)=x^2\) with its range limited to \(\left[0,\infty\right)\), which is now a one-to-one function (it passes the horizontal line test) and which has an inverse; namely, the square-root function \(\sqrt{x}\).

If \(f(x)=(x−1)^2\) on \([1,∞)\), then the inverse function is \(f^{-1}(x)=\sqrt{x}+1\).

- The domain of \(f\) = range of \(f^{-1} = \left[1,\infty\right)\).

- The domain of \(f^{-1}\) = range of \(f = \left[0,\infty\right)\).

![]() Is it possible for a function to have more than one inverse?

Is it possible for a function to have more than one inverse?

No. If two supposedly different functions, say \(g\) and \(h\), both meet the definition of being inverses of another function \(f\), then you can prove that \(g=h\). We have just seen that some functions only have inverses if we restrict the domain of the original function. In these cases, there may be more than one way to restrict the domain, leading to different inverses. However, on any one domain, the original function still has only one unique inverse.

Note: Domain and Range of Inverse Functions

The range of a function \(f(x)\) is the domain of the inverse function \(f^{-1}(x)\).

The domain of \(f(x)\) is the range of \(f^{-1}(x)\).

![]() Given a function, find the domain and range of its inverse

Given a function, find the domain and range of its inverse

- If the function is one-to-one, write the range of the original function as the domain of the inverse, and write the domain of the original function as the range of the inverse.

- If the domain of the original function needs to be restricted to make it one-to-one, then this restricted domain becomes the range of the inverse function.

![]() \(\PageIndex{4}\)

\(\PageIndex{4}\)

The domain of a one-to-one function \(f\) is \((1,\infty)\) and the range of function \(f\) is \((−\infty,−2)\). Find the domain and range of the inverse function.

- Answer

-

The domain of function \(f^{-1}\) is \((−\infty,−2)\) and the range of function \(f^{-1}\) is \((1,\infty)\).

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Finding the Inverses of Toolkit Functions

Identify which of the toolkit functions besides the quadratic function are not one-to-one, and find a restricted domain on which each function is one-to-one, if any. The toolkit functions are listed in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\).

We must restrict the domain in such a fashion that the function assumes all \(y\)-values exactly once.

| Constant | Identity | Quadratic | Cubic | Reciprocal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(f(x)=c\) | \(f(x)=x\) | \(f(x)=x^2\) | \(f(x)=x^3\) | \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\) |

| Reciprocal squared | Cube Root | Square Root | Absolute Value | |

| \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x^2}\) | \(f(x)=\sqrt[3]{x}\) | \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\) | \(f(x)=|x|\) |

Solution

The identity, cubic, reciprocal, cube root and square root functions are all one-to-one.

The constant function is not one-to-one, and the only domain on which it could be one-to-one is a set containing a single point, so the constant function has an inverse only if it has a restricted domain of a single input value.

The absolute value function can be restricted to the domain \(\left[0,\infty\right)\), where it is equal to the identity function.

The reciprocal-squared function can be restricted to the domain \((0,\infty)\).

Analysis

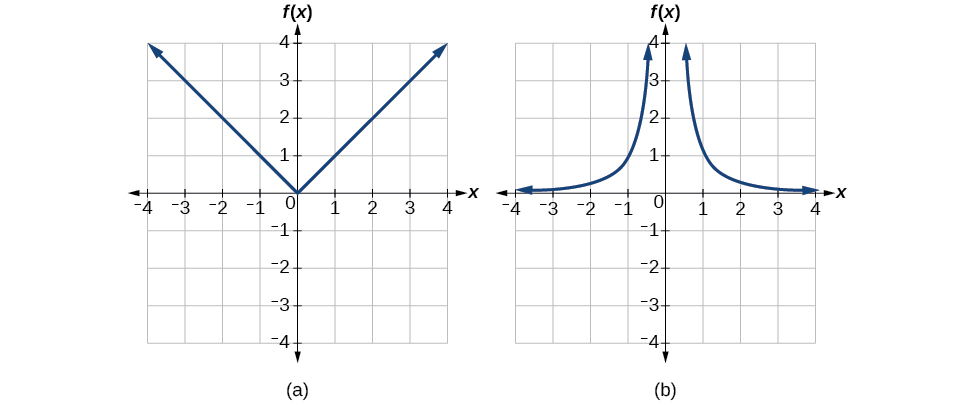

We can see that \(f(x) = |x|\) and \(f(x) = \frac{1}{x^2}\) (if unrestricted) are not one-to-one by looking at their graphs, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). They both would fail the horizontal line test. However, if a function is restricted to a certain domain so that it passes the horizontal line test, then in that restricted domain, it can have an inverse.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): (a) Absolute value (b) Reciprocal squared

Finding and Evaluating Inverse Functions

Once we have a one-to-one function, we can evaluate its inverse at specific inverse function inputs or construct a complete representation of the inverse function in many cases.

Inverting Tabular Functions

Suppose we want to find the inverse of a function represented in table form. Remember that the domain of a function is the range of the inverse and the range of the function is the domain of the inverse. So we need to interchange the domain and range.

Each row (or column) of inputs becomes the row (or column) of outputs for the inverse function. Similarly, each row (or column) of outputs becomes the row (or column) of inputs for the inverse function.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Interpreting the Inverse of a Tabular Function

A function \(f(t)\) is given in Table \(\PageIndex{3}\), showing distance in miles that a car has traveled in \(t\) minutes. Find and interpret \(f^{-1}(70)\)

|

\(t\) (minutes) |

30 | 50 | 70 | 90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

\(f(t)\) (miles) |

20 | 40 | 60 | 70 |

The inverse function takes an output of \(f\) and returns an input of \(f\). So in the expression \(f^{-1}(70)\), 70 is an output value of the original function, representing 70 miles. The inverse will return the corresponding input of the original function \(f\), 90 minutes, so \(f^{-1}(70)=90\). The interpretation of this is that, to drive 70 miles, it took 90 minutes.

Alternatively, recall that the definition of the inverse was that if \(f(a)=b\), then \(f^{-1}(b)=a\). By this definition, if we are given \(f^{-1}(70)=a\), then we are looking for a value \(a\) so that \(f(a)=70\). In this case, we are looking for a \(t\) so that \(f(t)=70\), which is when \(t=90\).

![]() \(\PageIndex{5}\)

\(\PageIndex{5}\)

Using Table \(\PageIndex{4}\), find and interpret (a) \(f(60)\),and (b) \(f^{-1}(60)\).

|

\(t\) (minutes) |

30 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

\(f(t)\) (miles) |

20 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 |

- Answer

-

\(f(60)=50\). In 60 minutes, 50 miles are traveled.

\(f^{-1}(60)=70\). To travel 60 miles, it will take 70 minutes.

Evaluating the Inverse of a Function, Given a Graph of the Original Function

We saw in Section 3.2 Functions and Function Notation that the domain of a function can be read by observing the horizontal extent of its graph. We find the domain of the inverse function by observing the vertical extent of the graph of the original function, because this corresponds to the horizontal extent of the inverse function. Similarly, we find the range of the inverse function by observing the horizontal extent of the graph of the original function, as this is the vertical extent of the inverse function. If we want to evaluate an inverse function, we find its input within its domain, which is all or part of the vertical axis of the original function’s graph.

![]() Given the graph of a function, evaluate its inverse at specific points

Given the graph of a function, evaluate its inverse at specific points

- Find the desired input on the \(y\)-axis of the given graph.

- Read the inverse function’s output from the \(x\)-axis of the given graph.

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\): Evaluating a Function and Its Inverse from a Graph at Specific Points

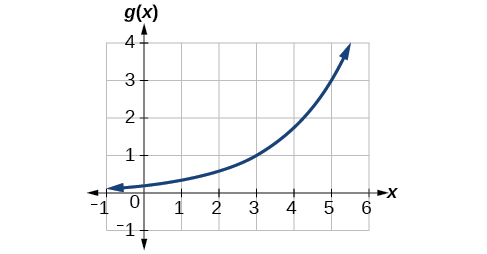

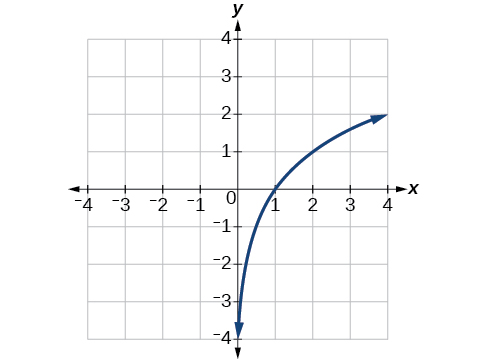

A function \(g(x)\) is given in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\). Find \(g(3)\) and \(g^{-1}(3)\).

.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Graph of \(g(x)\)

Solution

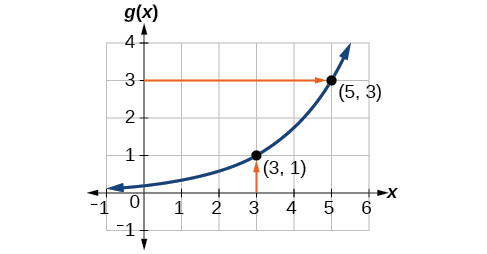

To evaluate \(g(3)\), we find 3 on the \(x\)-axis and find the corresponding output value on the \(y\)-axis. The point \((3,1)\) tells us that \(g(3)=1\).

To evaluate \(g^{-1}(3)\), recall that by definition, \(g^{-1}(3)\) means the value of \(x\) for which \(g(x)=3\). By looking for the output value 3 on the vertical axis, we find the point \((5,3)\) on the graph, which means \(g(5)=3\), so by definition, \(g^{-1}(3)=5.\) See Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Graph of \(g(x)\).

![]() \(\PageIndex{6}\)

\(\PageIndex{6}\)

Using the graph in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), (a) find \(g^{-1}(1)\), and (b) estimate \(g^{-1}(4)\).

- Answer

-

(a) 3

(b) about 5.6

Finding Inverses of Functions Represented by Formulas

Sometimes we will need to know an inverse function for all elements of its domain, not just a few. If the original function is given as a formula — for example, \(y\) as a function of \(x\) — we can often find the inverse function by solving to obtain \(x\) as a function of \(y\).

![]() Given a function represented by a formula, find the inverse.

Given a function represented by a formula, find the inverse.

- Make sure \(f\) is a one-to-one function.

- Solve for \(x\).

- Interchange \(x\) and \(y\).

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\): Inverting the Fahrenheit-to-Celsius Function

Given the function \(C=\dfrac{5}{9}(F−32)\) that gives Celsius temperature as a function of Fahrenheit temperature, find a formula for the inverse function that gives Fahrenheit temperature as a function of Celsius temperature.

Solution

\[\begin{align} C&=\frac{5}{9}(F-32) \nonumber \\ C{\cdot}\frac{9}{5}&=F−32 \nonumber \\ F&=\frac{9}{5}C+32 \nonumber \end{align} \nonumber\]

By solving in general, we have uncovered the inverse function. If\[C=h(F)=\dfrac{5}{9}(F−32), \nonumber\]

then

\[F=h^{-1}(C)=\dfrac{9}{5}C+32. \nonumber\]

In this case, we introduced a function \(h\) to represent the conversion because the input and output variables are descriptive, and writing \(C^{-1}\) could get confusing.

![]() \(\PageIndex{7}\)

\(\PageIndex{7}\)

Solve for \(x\) in terms of \(y\), given \(y=\frac{1}{3}(x−5)\).

- Answer

-

\(x=3y+5\)

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\): Solving a Formula to Find an Inverse Function

Find the inverse of the function \(f(x)=\frac{2}{x−3}+4\).

Solution

\[\begin{align} y&=\dfrac{2}{x−3}+4 &\text{Set up an equation.} \nonumber \\[3pt] y−4&=\dfrac{2}{x−3} &\text{Subtract 4 from both sides.} \nonumber \\[3pt] x−3&=\dfrac{2}{y−4} &\text{Multiply both sides by x−3 and divide by y−4.} \nonumber \\[3pt] x&=\dfrac{2}{y−4}+3 &\text{Add 3 to both sides.} \nonumber \end{align} \nonumber\]

So \(f^{-1}(y)=\frac{2}{y−4}+3\) or \(f^{-1}(x)=\frac{2}{x−4}+3\).

Extra Credit: The domain of \(f\) is \(\{x \;|\;x \neq 3\}\), while the domain of \(f^{-1}\) is \(\{x \;|\; x \neq 4\}\). What is the range of \(f\), and what is the range of \(f^{-1}\)? If you think you know the answer, explain your reasoning, and hand it in to your instructor.

Example \(\PageIndex{9}\): Solving a Formula to Find an Inverse with Radicals

Find the inverse of the function \(f(x)=2+\sqrt{x−4}\).

Solution

\[ \begin{align} y&=2+\sqrt{x-4} \nonumber\\ (y-2)^2&=x-4 \nonumber\\ x&=(y-2)^2+4 \nonumber\end{align} \nonumber\]

So \(f^{-1}(x)=(x−2)^2+4\).

The domain of \(f\) is \(\left[4,\infty\right)\). Notice that the range of \(f\) is \(\left[2,\infty\right)\), so this means that the domain of the inverse function \(f^{-1}\) is also \(\left[2,\infty\right)\).

Analysis

The formula we found for \(f^{-1}(x)\) looks like it would be valid for all real \(x\). However, \(f^{-1}\) itself must have an inverse (namely, \(f\)) so we have to restrict the domain of \(f^{-1}\) to \(\left[2,\infty\right)\) in order to make \(f^{-1}\) a one-to-one function. This domain of \(f^{-1}\) is exactly the range of \(f\).

![]() \(\PageIndex{8}\)

\(\PageIndex{8}\)

What is the inverse of the function \(f(x)=2-\sqrt{x}\)? State the domains of both the function and the inverse function.

- Answer

-

\(f^{-1}(x)=(2−x)^2\); domain of \(f\): \(D=\left[0,\infty\right)\); domain of \(f^{-1}\): \(D=\left(−\infty,2\right]\)

Finding Inverse Functions and Their Graphs

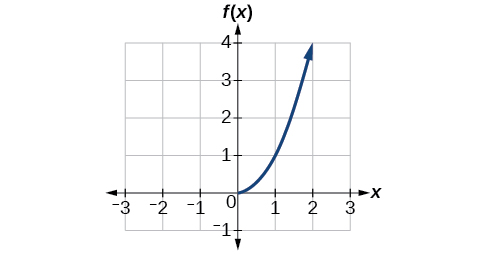

Now that we can find the inverse of a function, we will explore the graphs of functions and their inverses. Let us return to the quadratic function \(f(x)=x^2\) restricted to a domain \(\left[0,\infty\right)\), on which this function is one-to-one, and consider its graph, in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Quadratic function with domain restricted to \([0, \infty)\).

Restricting the domain to \(\left[0,\infty\right)\) makes the function one-to-one (it obviously passes the horizontal line test), so it has an inverse on this restricted domain.

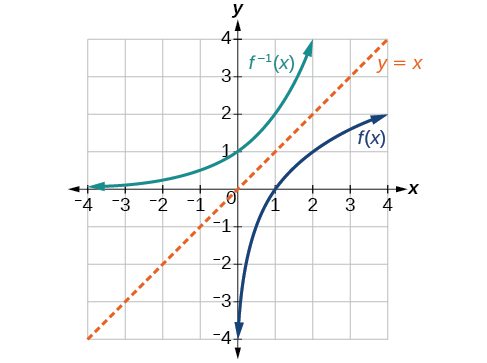

We already know that the inverse of the toolkit quadratic function is the square root function; that is, \(f^{-1}(x)=\sqrt{x}\). What happens if we graph both \(f\) and \(f^{-1}\) on the same set of axes, using the \(x\)-axis for the input to both \(f\) and \(f^{-1}\)?

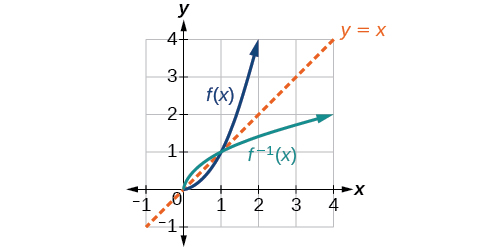

We notice a distinct relationship: The graph of \(f^{-1}(x)\) is the graph of \(f(x)\) reflected across the diagonal line \(y=x\), which we will call the identity line, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\).

.

.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Square and square-root functions on the non-negative domain

This graphical relationship holds true for all one-to-one functions and their inverses, because it is a result of the function and its inverse swapping inputs and outputs. This is equivalent to interchanging the roles of the vertical and horizontal axes.

Example \(\PageIndex{10}\): Finding the Inverse of a Function Using Reflection about the Identity Line

Given the graph of \(f(x)\) in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\), sketch a graph of \(f^{-1}(x)\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Graph of \(f(x)\).

This is a one-to-one function, so we will be able to sketch an inverse. Note that the graph shown has an apparent domain of \((0,\infty)\) and range of \((−\infty,\infty),\) so the inverse will have a domain of \((−\infty,\infty)\) and range of \((0,\infty)\).

If we reflect this graph over the line \(y=x\), the point \((1,0)\) reflects to \((0,1)\) and the point \((2,1)\) reflects to \((1,2)\). Sketching the inverse on the same axes as the original graph gives Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): The function and its inverse, showing reflection about the identity line

![]() \(\PageIndex{9}\)

\(\PageIndex{9}\)

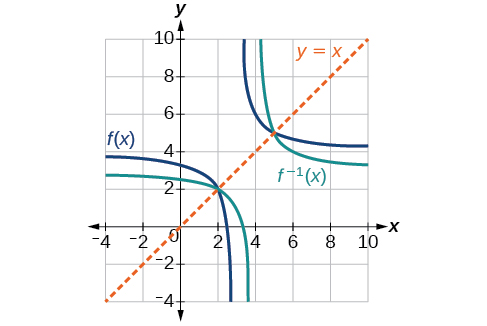

Draw graphs of the functions \(f\) and \(f^{-1}\) from Example \(\PageIndex{8}\).

- Answer

-

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\): Graph of \(f(x)\) and \(f^{-1}(x)\).

![]() Is there any function that is equal to its own inverse?

Is there any function that is equal to its own inverse?

Yes. If \(f=f^{-1}\), then \(f(f(x))=x\), and there are several functions that have this property. The identity function

does, and so does the reciprocal function, because

\[\dfrac{1}{\frac{1}{x}}=x. \nonumber\]

Any function \(f(x)=c−x\), where \(c\) is a constant, is also equal to its own inverse.

Note: Can you show that for \(f(x) = c-x,\; f(f(x)) = x\)? If you can, show your work carefully, and hand it in to your instructor for Extra Credit.

Key Concepts

- If \(g(x)\) is the inverse of \(f(x)\), then \(g(f(x))=f(g(x))=x\).

- For a function to have an inverse, it must be one-to-one (pass the horizontal line test).

- A function that is not one-to-one over its entire domain may be one-to-one on part of its domain.

- For a one-to-one tabular function, exchange the input and output rows to obtain the inverse.

- To find the inverse of a formula, solve the equation \(y=f(x)\) for \(x\) as a function of \(y\). Then exchange the labels \(x\) and \(y\).

- The graph of an inverse function is the reflection of the graph of the original function across the line \(y=x\).

Contributors

Jay Abramson (Arizona State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/precalculus.