9.2: Evaluate Logarithms and Graph Basic Logarithmic Equations

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Convert between exponential and logarithmic form

- Evaluate logarithmic expressions

- Graph basic logarithmic equations

- Solve logarithmic equations

- Use logarithmic models in applications

Before you get started, take this readiness quiz.

- Solve: x2=81.

- Evaluate: 3−2.

- Solve: 24=3x−5.

We have spent some time solving many basic equations. It works well to ‘undo’ an operation with another operation. Subtracting ‘undoes’ addition, multiplication ‘undoes’ division, taking the square root ‘undoes’ squaring.

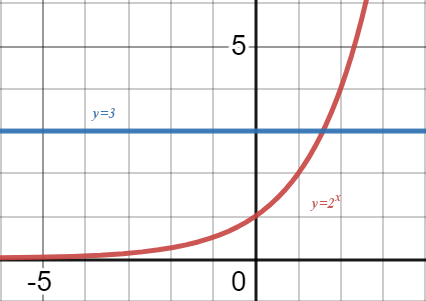

Because of the ono-to-one property of exponential expressions (for a≠1 and a>0, if ax=ay then x=y ), the equation ax=b has at most one solution. Also, it has a solution (as long as b>0 since ax>0 for all x). To see why this is so consider this (non-linear) system of equations

{y=by=ax.

The solution of this is also a solution to the equation ax=b and graphically it is seen as the intersection of the two curves, and they can be seen to intersect as long as b>0. Below is an example of such a situation.

We can approximate the solution by trial and error with a calculator. But this is time consuming. Sometimes, as we have seen, we can solve these equations by hand, and fortunately, in other cases, our calculator can provide us with an approximation (after a little work, depending on the calculator).

We use the standard notation for the solution to ax=b. The solution is written x=logab.

The solution to the equation x=ay is written

logax and is called the logarithm of x with base a, where a>0,x>0, and a≠1.

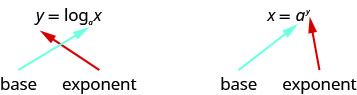

y=logax is equivalent to x=ay

Convert Between Exponential and Logarithmic Form

Since the equations y=logax and x=ay are equivalent, we can go back and forth between them. This will often be the method to solve some exponential and logarithmic equations. To help with converting back and forth let’s take a close look at the equations. See the figure below. Notice the positions of the exponent and base.

If we realize the logarithm is the exponent it makes the conversion easier. You may want to repeat, “base to the exponent give us the number.”

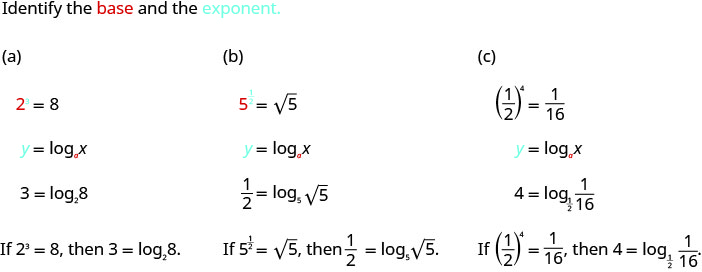

Convert to logarithmic form:

- 23=8

- 512=√5

- (12)x=116

Solution:

Convert to logarithmic form:

- 32=9

- 712=√7

- (13)x=127

- Answer

-

- log39=2

- log7√7=12

- log13127=x

Convert to logarithmic form:

- 43=64

- 413=3√4

- (12)x=132

- Answer

-

- log464=3

- log43√4=13

- log12132=x

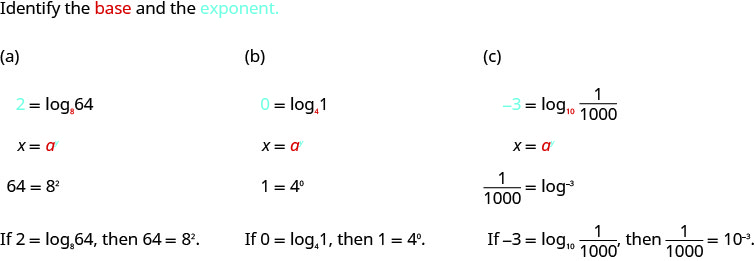

In the next example we do the reverse—convert logarithmic form to exponential form.

Convert to exponential form:

- 2=log864

- 0=log41

- −3=log1011000

Solution:

Convert to exponential form:

- 3=log464

- 0=logx1

- −2=log101100

- Answer

-

- 64=43

- 1=x0

- 1100=10−2

Convert to exponential form:

- 3=log327

- 0=logx1

- −1=log10110

- Answer

-

- 27=33

- 1=x0

- 110=10−1

Evaluate Logarithmic Expressions

We can solve and evaluate logarithmic equations by using the technique of converting the equation to its equivalent exponential equation.

Find the value of x:

a. logx36=2

b. log4x=3

c. log1218=x

Solution:

a.

logx36=2

Convert to exponential form.

x2=36

Solve the quadratic.

x=6,x=−6

The base of a logarithm must be positive, so we eliminate x=−6.

x=6 Therefore, log636=2

b.

log4x=3

Convert to exponential form.

43=x

Simplify.

x=64 Therefore ,log464=3

c.

log1218=x

Convert to exponential form.

(12)x=18

Rewrite 18 as (12)3.

(12)x=(12)3

With the same base, the exponents must be equal.

x=3 Therefore log1218=3

Find the value of x:

a. logx64=2

b. log5x=3

c. log1214=x

- Answer

-

a. x=8

b. x=125

c. x=2

Find the value of x:

a. logx81=2

b. log3x=5

c. log13127=x

- Answer

-

a. x=9

b. x=243

c. x=3

When see an expression such as log327, we can find its exact value two ways. By inspection we realize it means “3 to what power will be 27”? Since 33=27, we know log327=3. An alternate way is to set the expression equal to x and then convert it into an exponential equation.

Find the exact value of each logarithm without using a calculator:

a. log525

b. log93

c. log2116

Solution:

a.

log525

5 to what power will be 25?

log525=2

Or

Set the expression equal to x.

log525=x

Change to exponential form.

5x=25

Rewrite 25 as 52.

5x=52

With the same base the exponents must be equal.

x=2 Therefore ,log525=2.

b.

log93

Set the expression equal to x.

log93=x

Change to exponential form.

9x=3

Rewrite 9 as 32.

(32)x=31

Simplify the exponents.

32x=31

With the same base the exponents must be equal.

2x=1

Solve the equation.

x=12 Therefore ,log93=12.

c.

log2116

Set the expression equal to x.

log2116=x

Change to exponential form.

2x=116

Rewrite 16 as 24.

2x=124

2x=2−4

With the same base the exponents must be equal.

So, x=−4 and therefore log2116=−4

Find the exact value of each logarithm without using a calculator:

a. log12144

b. log42

c. log2132

- Answer

-

a. 2

b. 12

c. −5

Find the exact value of each logarithm without using a calculator:

a. log981

b. log82

c. log319

- Answer

-

a. 2

b. 13

c. −2

Optional: Graph Basic Logarithmic Equations

To graph a logarithmic equation y=logax, it is easiest to convert the equation to its exponential form, x=ay. Generally, when we look for ordered pairs for the graph of an equation, we usually choose an x-value and then determine its corresponding y-value. In this case you may find it easier to choose y-values and then determine its corresponding x-value.

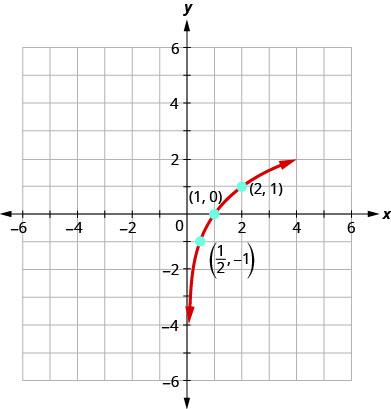

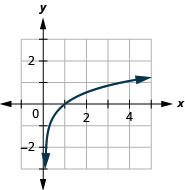

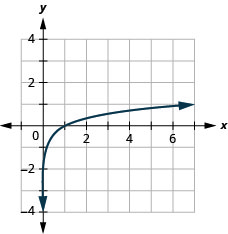

Graph y=log2x.

Solution:

To graph the equation, we will first rewrite the logarithmic equation, y=log2x, in exponential form, 2y=x. We can see that we have already graphed this (found the solutions to this equation, or rather the equation 2x=y from which we get the solutions by exchanging the order of the x−coordinate and the y−coordinate of each solution.)

Alternatively, we can use point plotting to graph the equation. It will be easier to start with values of y and then get x.

| y | 2y=x | (x,y) |

|---|---|---|

| −2 | 2−2=122=14 | (14,2) |

| −1 | 2−1=121=12 | (12,−1) |

| 0 | 20=1 | (1,0) |

| 1 | 21=2 | (2,1) |

| 2 | 22=4 | (4,2) |

| 3 | 23=8 | (8,3) |

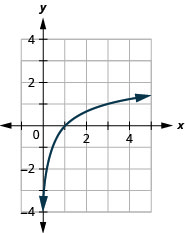

Graph: y=log3x.

- Answer

-

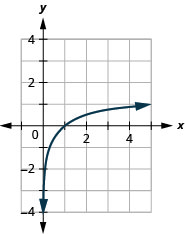

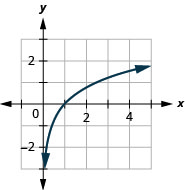

Graph: y=log5x.

- Answer

-

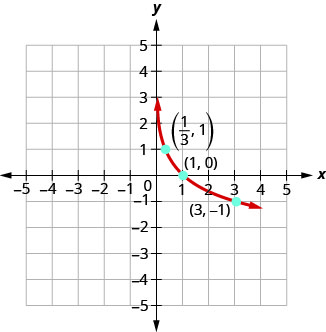

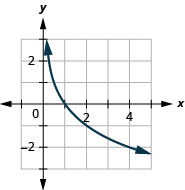

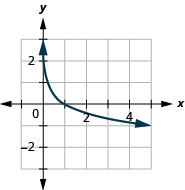

Graph y=log13x.

Solution:

To graph the equation, we will first rewrite the logarithmic equation, y=log13x, in exponential form, (13)y=x.

We will use point plotting to graph the equation. It will be easier to start with values of y and then get x.

| y | (13)y=x | (x,y) |

|---|---|---|

| −2 | (13)−2=32=9 | (9,−2) |

| −1 | (13)−1=31=3 | (3,−1) |

| 0 | (13)0=1 | (1,0) |

| 1 | (13)1=13 | (13,1) |

| 2 | (13)2=19 | (19,2) |

| 3 | (13)3=127 | (127,3) |

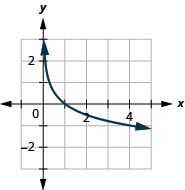

Graph: y=log12x.

- Answer

-

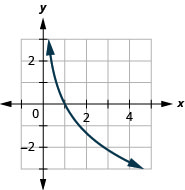

Graph: y=log14x.

- Answer

-

Solve Logarithmic Equations

When we talked about exponential expressions, we introduced the number e. Just as e was a base for an exponential expression, it can be used as a base for logarithms too. The logarithm with base e is called the natural logarithm. The expression logex is generally written lnx and we read it as “el en of x.”

logex=lnx is the natural logarithm where x>0.

y=lnx is equivalent to x=ey

When the base of the logarithm is 10, we call it the common logarithmic and the base is not shown. If the base a of a logarithm is not shown, we assume it is 10. Note that in some texts it is assumed to be e in this case.

log10x=logx is the common logarithm where x>0.

y=logx is equivalent to x=10y

To solve logarithmic equations, one strategy is to change the equation to exponential form and then solve the exponential equation as we did before. As we solve basic logarithmic equations, y=logax, we need to remember that for the base a, a>0 and a≠1. Also, x>0 since ay>0. Just as with radical equations, we must check our solutions to eliminate any extraneous solutions.

Solve:

a. loga49=2

b. lnx=3

Solution:

a. loga49=2

Rewrite in exponential form.

a2=49

Solve the equation using the square root property.

a=±7

The base cannot be negative, so we eliminate a=−7.

a=7,a=−7

Check. a=7

loga49=2log749?=272?=4949?=49 True

b.

lnx=3

Rewrite in exponential form.

e3=x

Check. x=e3

lnx=3lne3?=3e3?=e3 True

Solve:

a. loga121=2

b. lnx=7

- Answer

-

a. a=11

b. x=e7

Solve:

a. loga64=3

b. lnx=9

- Answer

-

a. a=4

b. x=e9

Solve:

a. log2(3x−5)=4

b. lne2x=4

Solution:

a.

log2(3x−5)=4

Rewrite in exponential form.

24=3x−5

Simplify.

16=3x−5

Solve the equation.

21=3x

7=x

Check. x=7

log2(3x−5)=4log2(3⋅7−5)?=4log2(16)?=424?=1616=16

b.

lne2x=4

Rewrite in exponential form.

e4=e2x

Since the bases are the same the exponents are equal.

4=2x

Solve the equation.

2=x

Check. x=2

lne2x=4lne2⋅2?=4lne4?=4e4?=e4 True

Solve:

a. log2(5x−1)=6

b. lne3x=6

- Answer

-

a. x=13

b. x=2

Solve:

a. log3(4x+3)=3

b. lne4x=4

- Answer

-

a. x=6

b. x=1

Use Logarithmic Models in Applications

There are many applications that are modeled by logarithmic equations. We will first look at the logarithmic equation that gives the decibel (dB) level of sound. Decibels range from 0, which is barely audible to 160, which can rupture an eardrum. The 10−12 in the formula represents the intensity of sound that is barely audible.

Decibel Level of Sound

The loudness level, D, measured in decibels, of a sound of intensity, I, measured in watts per square inch is

D=10log(I10−12)

Extended exposure to noise that measures 85 dB can cause permanent damage to the inner ear which will result in hearing loss. What is the decibel level of music coming through ear phones with intensity 10−2 watts per square inch?

Solution:

|

D=10log(I10−12) |

|

| Substitute in the intensity level, I. |

D=10log(10−210−12) |

| Simplify. |

D=10log(1010) |

| Since log1010=10. |

D=10⋅10 |

| Multiply. |

D=100 |

| The decibel level of music coming through earphones is 100 dB. |

What is the decibel level of one of the new quiet dishwashers with intensity 10−7 watts per square inch?

- Answer

-

The quiet dishwashers have a decibel level of 50 dB.

What is the decibel level heavy city traffic with intensity 10−3 watts per square inch?

- Answer

-

The decibel level of heavy traffic is 90 dB.

The magnitude R of an earthquake is measured by a logarithmic scale called the Richter scale. The model is R=logI, where I is the intensity of the shock wave. This model provides a way to measure earthquake intensity.

The magnitude R of an earthquake is measured byR=logI, where I is the intensity of its shock wave.

In 1906, San Francisco experienced an intense earthquake with a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale. Over 80% of the city was destroyed by the resulting fires. In 2014, Los Angeles experienced a moderate earthquake that measured 5.1 on the Richter scale and caused $108 million dollars of damage. Compare the intensities of the two earthquakes.

Solution:

To compare the intensities, we first need to convert the magnitudes to intensities using the log formula. Then we will set up a ratio to compare the intensities.

Convert the magnitudes to intensities.

R=logI

1906 earthquake

7.8=logI

Convert to exponential form.

I=107.8

2014 earthquake

5.1=logI

Convert to exponential form.

I=105.1

Form a ratio of the intensities.

Intensity for 1906 Intensity for 2014

Substitute in the values.

107.8105.1

Divide by subtracting the exponents.

102.7

Evaluate.

501

The intensity of the 1906 earthquake was about 501 times the intensity of the 2014 earthquake.

In 1906, San Francisco experienced an intense earthquake with a magnitude of 7.8 on the Richter scale. In 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake also affected the San Francisco area, and measured 6.9 on the Richter scale. Compare the intensities of the two earthquakes.

- Answer

-

The intensity of the 1906 earthquake was about 8 times the intensity of the 1989 earthquake.

In 2014, Chile experienced an intense earthquake with a magnitude of 8.2 on the Richter scale. In 2014, Los Angeles also experienced an earthquake which measured 5.1 on the Richter scale. Compare the intensities of the two earthquakes.

- Answer

-

The intensity of the earthquake in Chile was about 1,259 times the intensity of the earthquake in Los Angeles.

Key Concepts

- Evaluation of logarithms

- (Optional) Basic shape of the graph of y=logax for various a values.

- Decibel Level of Sound: The loudness level, D, measured in decibels, of a sound of intensity, I, measured in watts per square inch is D=10log(I10−12).

- Earthquake Intensity: The magnitude R of an earthquake is measured by R=logI, where I is the intensity of its shock wave.

Glossary

- common logarithm

- log10x=logx is the common logarithm, where x>0.

y=logx is equivalent to x=10y

- logarithm

- For a>0,a≠1 and x>0, the solution to the equation ay=x is denoted logax is called the logarithm of x with base a. y=logax is equivalent to x=ay

- natural logarithm

- logex=lnx is the natural logarithm, where x>0.

y=lnx is equivalent to x=ey

Practice Makes Perfect

Note that even answers are provided in this section.

In the following exercises, convert from exponential to logarithmic form.

- 42=16

- 25=32

- 33=27

- 53=125

- 103=1000

- 10−2=1100

- x12=√3

- x13=3√6

- 32x=4√32

- 17x=5√17

- (14)2=116

- (13)4=181

- 3−2=19

- 4−3=164

- ex=6

- e3=x

- Answer

-

2. log232=5

4. log5125=3

6. log1100=−2

8. logx3√6=13

10. log175√17=x

12. log13181=4

14. log4164=−3

16. lnx=3

In the following exercises, convert each logarithmic equation to exponential form.

- 3=log464

- 6=log264

- 4=logx81

- 5=logx32

- 0=log121

- 0=log71

- 1=log33

- 1=log99

- −4=log10110,000

- 3=log101,000

- 5=logex

- x=loge43

- Answer

-

18. 64=26

20. 32=x5

22. 1=70

24. 9=91

26. 1,000=103

28. 43=ex

In the following exercises, find the value of x in each logarithmic equation.

- logx49=2

- logx121=2

- logx27=3

- logx64=3

- log3x=4

- log5x=3

- log2x=−6

- log3x=−5

- log14116=x

- log1319=x

- log1464=x

- log1981=x

- Answer

-

30. x=11

32. x=4

34. x=125

36. x=1243

38. x=2

40. x=−2

In the following exercises, find the exact value of each logarithm without using a calculator.

- log749

- log636

- log41

- log51

- log164

- log273

- log122

- log124

- log2116

- log3127

- log4116

- log9181

- Answer

-

42. 2

44. 0

46. 13

48. −2

50. −3

52. −2

In the following exercises, graph each logarithmic function.

- y=log2x

- y=log4x

- y=log6x

- y=log7x

- y=log1.5x

- y=log2.5x

- y=log13x

- y=log15x

- y=log0.4x

- y=log0.6x

- Answer

-

54.

56.

58.

60.

62.

In the following exercises, solve each logarithmic equation.

- loga16=2

- loga81=2

- loga8=3

- loga27=3

- loga32=2

- loga24=3

- lnx=5

- lnx=4

- log2(5x+1)=4

- log2(6x+2)=5

- log3(4x−3)=2

- log3(5x−4)=4

- log4(5x+6)=3

- log4(3x−2)=2

- lne4x=8

- lne2x=6

- logx2=2

- log(x2−25)=2

- log2(x2−4)=5

- log3(x2+2)=3

- Answer

-

64. a=9

66. a=3

68. a=3√24

70. x=e4

72. x=5

74. x=17

76. x=6

78. x=3

80. x=−5√5,x=5√5

82. x=−5,x=5

In the following exercises, use a logarithmic model to solve.

- What is the decibel level of normal conversation with intensity 10−6 watts per square inch?

- What is the decibel level of a whisper with intensity 10−10 watts per square inch?

- What is the decibel level of the noise from a motorcycle with intensity 10−2 watts per square inch?

- What is the decibel level of the sound of a garbage disposal with intensity 10−2 watts per square inch?

- In 2014, Chile experienced an intense earthquake with a magnitude of 8.2 on the Richter scale. In 2010, Haiti also experienced an intense earthquake which measured 7.0 on the Richter scale. Compare the intensities of the two earthquakes.

- The Los Angeles area experiences many earthquakes. In 1994, the Northridge earthquake measured magnitude of 6.7 on the Richter scale. In 2014, Los Angeles also experienced an earthquake which measured 5.1 on the Richter scale. Compare the intensities of the two earthquakes.

- Answer

-

84. A whisper has a decibel level of 20 dB.

86. The sound of a garbage disposal has a decibel level of 100 dB.

88. The intensity of the 1994 Northridge earthquake in the Los Angeles area was about 40 times the intensity of the 2014 earthquake.

- Explain how to change an equation from logarithmic form to exponential form.

- Explain the difference between common logarithms and natural logarithms.

- Explain why logaax=x.

- Explain how to find the log732 on your calculator.

- Answer

-

90. Answers may vary

92. Answers may vary

Self Check

a. After completing the exercises, use this checklist to evaluate your mastery of the objectives of this section.

| I can... | Confidently | With some help | No- I don't get it! |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convert between exponential and logarithmic form. | |||

| Evaluate logarithms. | |||

| Graph basic logarithmic equations. | |||

| Solve logarithm equations. | |||

| Use logarithmic models in applications. |

b. After reviewing this checklist, what will you do to become confident for all objectives?