1.4: Decimals

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 79411

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Round decimals

- Add and subtract decimals

- Multiply and divide decimals

- Convert decimals, fractions, and percents

- Simplify expressions with square roots

- Identify integers, rational numbers, irrational numbers, and real numbers

- Locate fractions and decimals on the number line

A more thorough introduction to the topics covered in this section can be found in the Elementary Algebra chapter, Foundations.

Round Decimals

Decimals are another way of writing fractions whose denominators are powers of ten.

\[\begin{array}{rcll} 0.1 & = & \dfrac{1}{10} & \text{is “one tenth”} \\ 0.01 & = & \dfrac{1}{100} & \text{is “one hundredth”} \\ 0.001 & = & \dfrac{1}{1000} & \text{is “one thousandth”} \\ 0.0001 & = & \dfrac{1}{10,000} & \text{is “one ten-thousandth”} \end{array}\]

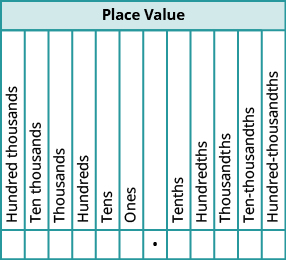

Just as in whole numbers, each digit of a decimal corresponds to the place value based on the powers of ten. Figure shows the names of the place values to the left and right of the decimal point.

When we work with decimals, it is often necessary to round the number to the nearest required place value. We summarize the steps for rounding a decimal here.

ROUND DECIMALS.

- Locate the given place value and mark it with an arrow.

- Underline the digit to the right of the place value.

- Is the underlined digit greater than or equal to 5?

- Yes: add 1 to the digit in the given place value.

- No: do not change the digit in the given place value

- Rewrite the number, deleting all digits to the right of the rounding digit.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Round \(18.379\) to the nearest ⓐ hundredth ⓑ tenth ⓒ whole number.

- Answer

-

Round \(18.379.\)

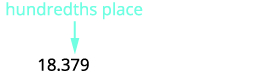

ⓐ to the nearest hundredth

Locate the hundredths place with an arrow.

Underline the digit to the right of the given place value.

Because 9 is greater than or equal to 5, add 1 to the 7.

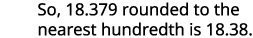

Rewrite the number, deleting all digits to the right of the rounding digit.

Notice that the deleted digits were NOT replaced with zeros.

ⓑ to the nearest tenth

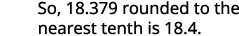

Locate the tenths place with an arrow.

Underline the digit to the right of the given place value.

Because 7 is greater than or equal to 5, add 1 to the 3.

Rewrite the number, deleting all digits to the right of the rounding digit.

Notice that the deleted digits were NOT replaced with zeros.

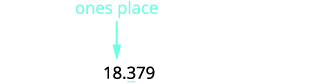

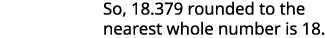

ⓒ to the nearest whole number

Locate the ones place with an arrow.

Underline the digit to the right of the given place value.

Since 3 is not greater than or equal to 5, do not add 1 to the 8.

Rewrite the number, deleting all digits to the right of the rounding digit.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Round \(6.582\) to the nearest ⓐ hundredth ⓑ tenth ⓒ whole number.

- Answer

-

ⓐ \(6.58\) ⓑ \(6.6\) ⓒ \(7\)

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Round \(15.2175\) to the nearest ⓐ thousandth ⓑ hundredth ⓒ tenth.

- Answer

-

ⓐ \(15.218\) ⓑ \(15.22\)

ⓒ \(15.2\)

Add and Subtract Decimals

To add or subtract decimals, we line up the decimal points. By lining up the decimal points this way, we can add or subtract the corresponding place values. We then add or subtract the numbers as if they were whole numbers and then place the decimal point in the sum.

ADD OR SUBTRACT DECIMALS.

- Determine the sign of the sum or difference.

- Write the numbers so the decimal points line up vertically.

- Use zeros as placeholders, as needed.

- Add or subtract the numbers as if they were whole numbers. Then place the

decimal point in the answer under the decimal points in the given numbers. - Write the sum or difference with the appropriate sign.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Add or subtract: ⓐ \(−23.5−41.38\) ⓑ \(14.65−20.\)

- Answer

-

ⓐ

\(\begin{array}{ll} \text{} & −23.5−41.38 \\ \\ \\ {\text{The difference will be negative. To subtract, we add the} \\ \text{numerals. Write the numbers so the decimal points line} \\ \text{up vertically.}} & { \; \; 23.5 \\ \underline{+41.38}} \\ \\ \\ { \text{Put 0 as a placeholder after the 5 in 23.5.} \\ \text{Remember, } \frac{5}{10}=\frac{50}{100} \text{ so } 0.5=0.50.} & { \; \; 23.50 \\ \underline{+41.38}} \\ \\ \\ {\text{Add the numbers as if they were whole numbers.} \\ \text{Then place the decimal point in the sum.}} & {\; \; 23.50 \\ \underline{+41.38} \\ \; \; 64.88 } \\ \\ \\ \text{ Write the result with the correct sign.} & 64.88−23.5−41.38=−64.88 \end{array}\)

ⓑ

\(\begin{array}{ll} \text{} & 14.65−20 \\ \\ \\ {\text{The difference will be negative. To subtract, we} \\ \text{subtract 14.65 from 20.}} \\ \\ \\ {\text{Write the numbers so the decimal points line up} \\ \text{vertically.}} & { \; \; 20 \\ \underline{−14.65}} \\ \\ \\ {\text{Remember, 20 is a whole number, so place the} \\ \text{decimal point after the 0.}} \\ \\ \\ \text{Put in zeros to the right as placeholders.} & { \; \; 20.00 \\ \underline{−14.65}} \\ \\ \\ \text{Subtract and place the decimal point in the answer.} & {\begin{array}{lcccc} {} & 9 & {} & 9 & {} \\ 1 & \cancel{10} & {} & \cancel{10} & 10 \\ 2 & 0 & . & 0 & 0 \\ −1 & 4 & . & 6 & 5 \end{array} \\ \text{______________________} \\ \begin{array}{lcccc} {\; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; } & 5 & . & 3 & 5 \end{array}} \\ \\ \\ \text{Write the result with the correct sign.} & 14.65−20=−5.35 \end{array} \)

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Add or subtract: ⓐ \(−4.8−11.69\) ⓑ\(9.58−10\).

- Answer

-

ⓐ \(−16.49\) ⓑ \(−0.42\)

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Add or subtract: ⓐ \(−5.123−18.47\) ⓑ\(37.42−50\).

- Answer

-

ⓐ \(−23.593\) ⓑ\(−12.58\)

Multiply and Divide Decimals

When we multiply signed decimals, first we determine the sign of the product and then multiply as if the numbers were both positive. We multiply the numbers temporarily ignoring the decimal point and then count the number of decimal points in the factors and that sum tells us the number of decimal places in the product. Finally, we write the product with the appropriate sign.

MULTIPLY DECIMALS.

- Determine the sign of the product.

- Write in vertical format, lining up the numbers on the right. Multiply the numbers as if they were whole numbers, temporarily ignoring the decimal points.

- Place the decimal point. The number of decimal places in the product is the sum of

the number of decimal places in the factors. - Write the product with the appropriate sign.

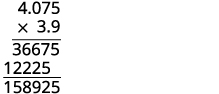

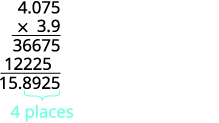

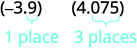

Multiply: \((−3.9)(4.075)\).

- Answer

-

\((−3.9)(4.075)\) The signs are different. The product

will be negative.The product will be negative. Write in vertical format, lining up the

numbers on the right.

Multiply.

Add the number of decimal places in

the factors (1 + 3). Place the decimal point 4 places from the right.

The signs are the different, so the product is negative. \((−3.9)(4.075)=−15.8925\)

Multiply: \(−4.5(6.107)\).

- Answer

-

\(−27.4815\)

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Multiply: \(−10.79(8.12)\).

- Answer

-

\(−87.6148\)

Often, especially in the sciences, you will multiply decimals by powers of 10 (10, 100, 1000, etc). If you multiply a few products on paper, you may notice a pattern relating the number of zeros in the power of 10 to number of decimal places we move the decimal point to the right to get the product.

MULTIPLY A DECIMAL BY A POWER OF TEN.

- Move the decimal point to the right the same number of places as the

number of zeros in the power of 10. - Add zeros at the end of the number as needed.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{10}\)

Multiply: 5.63 by ⓐ 10 ⓑ 100 ⓒ 1000.

- Answer

-

By looking at the number of zeros in the multiple of ten, we see the number of places we need to move the decimal to the right.

ⓐ

There is 1 zero in 10, so move the decimal point 1 place to the right.

ⓑ

There are 2 zeroes in 100, so move the decimal point 2 places to the right.

ⓒ

There are 3 zeroes in 1,000, so move the decimal point 3 place to the right.

A zero must be added to the end.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{11}\)

Multiply 2.58 by ⓐ 10 ⓑ 100 ⓒ 1000.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 25.8 ⓑ 258 ⓒ 2,580

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{12}\)

Multiply 14.2 by ⓐ 10 ⓑ 100 ⓒ 1000.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 142 ⓑ 1,420 ⓒ 14,200

Just as with multiplication, division of signed decimals is very much like dividing whole numbers. We just have to figure out where the decimal point must be placed and the sign of the quotient. When dividing signed decimals, first determine the sign of the quotient and then divide as if the numbers were both positive. Finally, write the quotient with the appropriate sign.

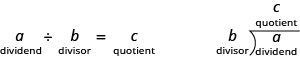

We review the notation and vocabulary for division:

We’ll write the steps to take when dividing decimals for easy reference.

DIVIDE DECIMALS.

- Determine the sign of the quotient.

- Make the divisor a whole number by “moving” the decimal point all the way to the right. “Move” the decimal point in the dividend the same number of places—adding zeros as needed.

- Divide. Place the decimal point in the quotient above the decimal point in the dividend.

- Write the quotient with the appropriate sign.

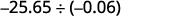

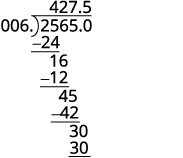

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{13}\)

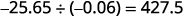

Divide: \(−25.65÷(−0.06)\).

- Answer

-

Remember, you can “move” the decimals in the divisor and dividend because of the Equivalent Fractions Property.

The signs are the same. The quotient is positive. Make the divisor a whole number by “moving” the decimal point all the way to the right. “Move” the decimal point in the dividend the same number of places.

Divide. Place the decimal point in the quotient above the decimal point in the dividend.

Write the quotient with the appropriate sign.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{14}\)

Divide: \(−23.492÷(−0.04)\).

- Answer

-

\(587.3\)

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{15}\)

Divide: \(−4.11÷(−0.12)\).

- Answer

-

\(34.25\)

Convert Decimals, Fractions, and Percents

In our work, it is often necessary to change the form of a number. We may have to change fractions to decimals or decimals to percent.

We convert decimals into fractions by identifying the place value of the last (farthest right) digit. In the decimal 0.03. the 3 is in the hundredths place, so 100 is the denominator of the fraction equivalent to 0.03.

\[0.03=\dfrac{3}{100}\]

The steps to take to convert a decimal to a fraction are summarized in the procedure box.

CONVERT A DECIMAL TO A PROPER FRACTION AND A FRACTION TO A DECIMAL.

- To convert a decimal to a proper fraction, determine the place value of the final digit.

- Write the fraction.

- numerator—the “numbers” to the right of the decimal point

- denominator—the place value corresponding to the final digit

- To convert a fraction to a decimal, divide the numerator of the fraction by the denominator of the fraction.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{16}\)

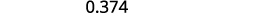

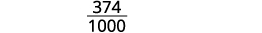

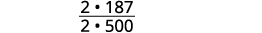

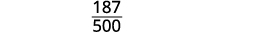

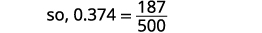

Write: ⓐ \(0.374\) as a fraction ⓑ \(−\frac{5}{8}\) as a decimal.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

Determine the place value of the final digit.

Write the fraction for 0.374: The numerator is 374. The denominator is 1,000.

Simplify the fraction.

Divide out the common factors.

ⓑ Since a fraction bar means division, we begin by writing the fraction \(\frac{5}{8}\) as \(8\sqrt{5}\). Now divide.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{17}\)

Write: ⓐ \(0.234\) as a fraction ⓑ \(−\frac{7}{8}\) as a decimal.

- Answer

-

ⓐ\(\frac{117}{500}\) ⓑ \(−0.875\)

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{18}\)

Write: ⓐ \(0.024\) as a fraction ⓑ \(−\frac{3}{8}\) as a decimal.

- Answer

-

ⓐ\(\frac{3}{125}\) ⓑ \(−0.375\)

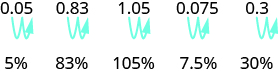

A percent is a ratio whose denominator is 100. Percent means per hundred. We use the percent symbol, %, to show percent. Since a percent is a ratio, it can easily be expressed as a fraction. Percent means per 100, so the denominator of the fraction is 100. We then change the fraction to a decimal by dividing the numerator by the denominator. After doing this many times, you may see the pattern.

To convert a percent number to a decimal number, we move the decimal point two places to the left.

To convert a decimal to a percent, remember that percent means per hundred. If we change the decimal to a fraction whose denominator is 100, it is easy to change that fraction to a percent. After many conversions, you may recognize the pattern.

To convert a decimal to a percent, we move the decimal point two places to the right and then add the percent sign.

CONVERT A PERCENT TO A DECIMAL AND A DECIMAL TO A PERCENT.

- To convert a percent to a decimal, move the decimal point two places to the left after removing the percent sign.

- To convert a decimal to a percent, move the decimal point two places to the right and then add the percent sign.

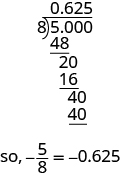

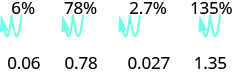

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{19}\)

Convert each:

ⓐ percent to a decimal: 62%, 135%, and 13.7%.

ⓑ decimal to a percent: 0.51, 1.25, and 0.093.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

Move the decimal point two places to the left.

ⓑ

Move the decimal point two places to the right.

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{20}\)

Convert each:

ⓐ percent to a decimal: 9%, 87%, and 3.9%.

ⓑ decimal to a percent: 0.17, 1.75, and 0.0825.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 0.09, 0.87, 0.039 ⓑ 17%, 175%, 8.25%

EXAMPLE \(\PageIndex{21}\)

Convert each:

ⓐ percent to a decimal: 3%, 91%, and 8.3%.

ⓑ decimal to a percent: 0.41, 2.25, and 0.0925.

- Answer

-

ⓐ 0.03, 0.91, 0.083 ⓑ 41%, 225%, 9.25%

Simplify Expressions with Square Roots

Remember that when a number \(n\) is multiplied by itself, we write \(n^2\) and read it “\(n\) squared.” The result is called the square of a number n. For example, \(\frac{8}{2}\) is read “8 squared” and 64 is called the square of 8. Similarly, 121 is the square of 11 because \(11^2\) is 121. It will be helpful to learn to recognize the perfect square numbers.

SQUARE OF A NUMBER

If \(n^2=m\), then m is the square of n.

What about the squares of negative numbers? We know that when the signs of two numbers are the same, their product is positive. So the square of any negative number is also positive.

\[(−3)^2=9 \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; (−8)^2=64 \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; (−11)^2=121 \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; (−15)^2=225\]

Because \(10^2=100\), we say 100 is the square of 10. We also say that 10 is a square root of 100. A number whose square is m is called a square root of a number m.

SQUARE ROOT OF A NUMBER

If \(n^2=m\), then n is a square root of m.

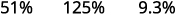

Notice \((−10)^2=100\) also, so −10 is also a square root of 100. Therefore, both 10 and −10 are square roots of 100. So, every positive number has two square roots—one positive and one negative. The radical sign, \(\sqrt{m}\), denotes the positive square root. The positive square root is called the principal square root. When we use the radical sign that always means we want the principal square root.

SQUARE ROOT NOTATION

\(\sqrt{m}\) is read “the square root of mm.”

If \(m=n^2\), then \(\sqrt{m}=n\), for \(n≥0\).

The square root of m, \(\sqrt{m}\), is the positive number whose square is m.

We know that every positive number has two square roots and the radical sign indicates the positive one. We write \(\sqrt{100}=10\). If we want to find the negative square root of a number, we place a negative in front of the radical sign. For example, \(−\sqrt{100}=−10\). We read \(−\sqrt{100}\) as “the opposite of the principal square root of 10.”

Exercise \(\PageIndex{22}\)

Simplify: ⓐ \(\sqrt{25}\) ⓑ \(\sqrt{121}\) ⓒ \(−\sqrt{144}\).

- Answer

-

ⓐ

\(\begin{array}{ll} \text{} & \sqrt{25} \\ \text{Since }5^2=25 & 5 \end{array}\)ⓑ

\(\begin{array}{ll} \text{} & \sqrt{121} \\ \text{Since }11^2=121 & 11 \end{array}\)

ⓒ

\(\begin{array}{ll} {} & −\sqrt{144} \\ \text{The negative is in front of} & −12 \\ \text{the radical sign.} \end{array}\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{23}\)

Simplify: ⓐ \(\sqrt{36}\) ⓑ \(\sqrt{169}\) ⓒ \(−\sqrt{225}\)

- Answer

-

ⓐ 6 ⓑ 13 ⓒ −15

Exercise \(\PageIndex{24}\)

Simplify: ⓐ \(\sqrt{16}\) ⓑ \(\sqrt{196}\) ⓒ \(−\sqrt{100}\)

- Answer

-

ⓐ 4 ⓑ 14 ⓒ −10

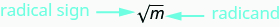

Identify Integers, Rational Numbers, Irrational Numbers, and Real Numbers

We have already described numbers as counting numbers, whole numbers, and integers. What is the difference between these types of numbers? Difference could be confused with subtraction. How about asking how we distinguish between these types of numbers?

\[\begin{array}{ll} \text{Counting numbers} & 1,2,3,4,….. \\ \text{Whole numbers} & 0,1,2,3,4,…. \\ \text{Integers} & ….−3,−2,−1,0,1,2,3,…. \end{array}\]

What type of numbers would we get if we started with all the integers and then included all the fractions? The numbers we would have form the set of rational numbers. A rational number is a number that can be written as a ratio of two integers.

In general, any decimal that ends after a number of digits (such as 7.3 or −1.2684) is a rational number. We can use the place value of the last digit as the denominator when writing the decimal as a fraction. The decimal for \(\frac{1}{3}\) is the number \(0.\overline{3}\). The bar over the 3 indicates that the number 3 repeats infinitely. Continuously has an important meaning in calculus. The number(s) under the bar is called the repeating block and it repeats continuously.

Since all integers can be written as a fraction whose denominator is 1, the integers (and so also the counting and whole numbers. are rational numbers.

Every rational number can be written both as a ratio of integers \(\frac{p}{q}\), where p and q are integers and \(q≠0\), and as a decimal that stops or repeats.

RATIONAL NUMBER

A rational number is a number of the form \(\frac{p}{q}\), where p and q are integers and \(q≠0\).

Its decimal form stops or repeats.

Are there any decimals that do not stop or repeat? Yes! The number ππ (the Greek letter pi, pronounced “pie”), which is very important in describing circles, has a decimal form that does not stop or repeat. We use three dots (…) to indicate the decimal does not stop or repeat.

\[π=3.141592654...\]

The square root of a number that is not a perfect square is a decimal that does not stop or repeat.

A numbers whose decimal form does not stop or repeat cannot be written as a fraction of integers. We call this an irrational number.

IRRATIONAL NUMBER

An irrational number is a number that cannot be written as the ratio of two integers.

Its decimal form does not stop and does not repeat.

Let’s summarize a method we can use to determine whether a number is rational or irrational.

RATIONAL OR IRRATIONAL

If the decimal form of a number

- repeats or stops, the number is a rational number.

- does not repeat and does not stop, the number is an irrational number.

We have seen that all counting numbers are whole numbers, all whole numbers are integers, and all integers are rational numbers. The irrational numbers are numbers whose decimal form does not stop and does not repeat. When we put together the rational numbers and the irrational numbers, we get the set of real numbers.

REAL NUMBER

A real number is a number that is either rational or irrational.

Later in this course we will introduce numbers beyond the real numbers. Figure illustrates how the number sets we’ve used so far fit together.

Does the term “real numbers” seem strange to you? Are there any numbers that are not “real,” and, if so, what could they be? Can we simplify \(−\sqrt{25}\)? Is there a number whose square is \(−25\)?

\[()^2=−25?\]

None of the numbers that we have dealt with so far has a square that is \(−25\). Why? Any positive number squared is positive. Any negative number squared is positive. So we say there is no real number equal to \(\sqrt{−25}\). The square root of a negative number is not a real number.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{25}\)

Given the numbers \(−7,\frac{14}{5},8,\sqrt{5},5.9,−\sqrt{64}\), list the ⓐ whole numbers ⓑ integers ⓒ rational numbers ⓓ irrational numbers ⓔreal numbers.

- Answer

-

ⓐ Remember, the whole numbers are \(0,1,2,3,…,\) so 8 is the only whole number given.

ⓑ The integers are the whole numbers and their opposites (which includes 0). So the whole number 8 is an integer, and −7 is the opposite of a whole number so it is an integer, too. Also, notice that 64 is the square of 8 so \(−\sqrt{64}=−8\). So the integers are \(−7,8,\) and \(−\sqrt{64}\).

ⓒ Since all integers are rational, then \(−7,8,\) and \(−\sqrt{64}\) are rational. Rational numbers also include fractions and decimals that repeat or stop, so \(\frac{14}{5}\) and \(5.9\) are rational. So the list of rational numbers is \(−7,\frac{14}{5},8,5.9,\) and \(−\sqrt{64}\).

ⓓ Remember that 5 is not a perfect square, so \(\sqrt{5}\) is irrational.

ⓔ All the numbers listed are real numbers.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{26}\)

Given the numbers \(−3,−\sqrt{2},0.\overline{3},\frac{9}{5},4,\sqrt{49},\) list the ⓐ whole numbers ⓑ integers ⓒ rational numbers

ⓓ irrational numbers ⓔ real numbers.

- Answer

-

ⓐ \(4,\sqrt{49}\) ⓑ \(−3,4,\sqrt{49}\)

ⓒ \(−3,0.\overline{3},\frac{9}{5},4,\sqrt{49}\) ⓓ \(−\sqrt{2}\)ⓔ \(−3,−\sqrt{2},0.\overline{3},\frac{9}{5},4,\sqrt{49}\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{27}\)

Given numbers \(−\sqrt{25},−\frac{3}{8},−1,6,\sqrt{121},2.041975...,\) list the ⓐ whole numbers ⓑ integers ⓒ rational numbers ⓓ irrational numbers ⓔ real numbers.

- Answer

-

ⓐ \(6,\sqrt{121}\)

ⓑ \(−\sqrt{25},−1,6,\sqrt{121}\)

ⓒ \(−\sqrt{25},−\frac{3}{8},−1,6,\sqrt{121}\)

ⓓ \(2.041975...\)

ⓔ \(−\sqrt{25},−\frac{3}{8},−1,6,\sqrt{121},2.041975...\)

Locate Fractions and Decimals on the Number Line

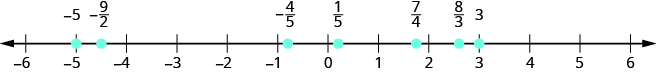

We now want to include fractions and decimals on the number line. Let’s start with fractions and locate \(\frac{1}{5},−\frac{4}{5},3,\frac{7}{4},−\frac{9}{2},−5\) and \(\frac{8}{3}\) on the number line.

We’ll start with the whole numbers 3 and −5 because they are the easiest to plot. See Figure.

The proper fractions listed are \(\frac{1}{5}\) and \(−\frac{4}{5}.\) We know the proper fraction \(\frac{1}{5}\) has value less than one and so would be located between 0 and 1. The denominator is 5, so we divide the unit from 0 to 1 into 5 equal parts \(\frac{1}{5},\frac{2}{5},\frac{3}{5},\frac{4}{5}\). We plot \(\frac{1}{5}\).

Similarly, \(−\frac{4}{5}\) is between 0 and −1. After dividing the unit into 5 equal parts we plot \(−\frac{4}{5}\).

Finally, look at the improper fractions \(\frac{7}{4},\frac{9}{2},\frac{8}{3}\). Locating these points may be easier if you change each of them to a mixed number.

\[\dfrac{7}{4}=1\dfrac{3}{4} \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; −\dfrac{9}{2}=−4\dfrac{1}{2} \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; \dfrac{8}{3}=2\dfrac{2}{3}\]

Figure shows the number line with all the points plotted.

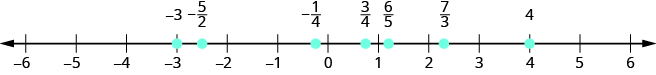

Exercise \(\PageIndex{28}\)

Locate and label the following on a number line: \(4,\frac{3}{4},−\frac{1}{4},−3,\frac{6}{5},−\frac{5}{2},\) and \(\frac{7}{3}\).

- Answer

-

Locate and plot the integers, \(4,−3.\)

Locate the proper fraction \(\frac{3}{4}\) first. The fraction \(\frac{3}{4}\) is between 0 and 1. Divide the distance between 0 and 1 into four equal parts, then we plot \(\frac{3}{4}\). Similarly plot \(−\frac{1}{4}\).

Now locate the improper fractions \(\frac{6}{5},−\frac{5}{2},\) and \(\frac{7}{3}\). It is easier to plot them if we convert them to mixed numbers and then plot them as described above: \(\frac{6}{5}=1\frac{1}{5},−\frac{5}{2}=−2\frac{1}{2},\frac{7}{3}=2\frac{1}{3}\).

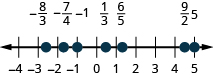

Exercise \(\PageIndex{29}\)

Locate and label the following on a number line: \(−1,\frac{1}{3},\frac{6}{5},−\frac{7}{4},\frac{9}{2},5,−\frac{8}{3}\).

- Answer

-

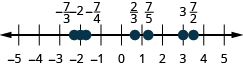

Exercise \(\PageIndex{30}\)

Locate and label the following on a number line: \(−2,\frac{2}{3},\frac{7}{5},−\frac{7}{4},\frac{7}{2},3,−\frac{7}{3}\).

- Answer

-

Exercise \(\PageIndex{31}\)

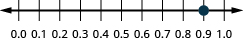

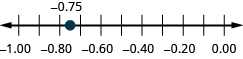

Since decimals are forms of fractions, locating decimals on the number line is similar to locating fractions on the number line.

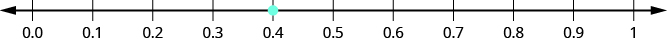

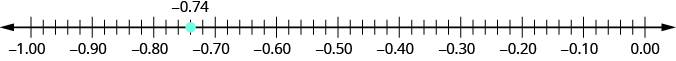

Locate on the number line: ⓐ 0.4 ⓑ −0.74.

- Answer

-

ⓐ The decimal number 0.4 is equivalent to \(\frac{4}{10}\), a proper fraction, so 0.4 is located between 0 and 1. On a number line, divide the interval between 0 and 1 into 10 equal parts. Now label the parts 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0. We write 0 as 0.0 and 1 as 1.0, so that the numbers are consistently in tenths. Finally, mark 0.4 on the number line.

ⓑ The decimal \(−0.74\) is equivalent to \(−\frac{74}{100}\), so it is located between 0 and .−1. On a number line, mark off and label the hundredths in the interval between 0 and −1.

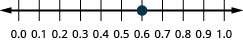

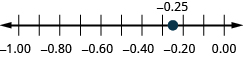

Exercise \(\PageIndex{32}\)

Locate on the number line: ⓐ \(0.6\) ⓑ \(−0.25.\)

- Answer

-

ⓐ

ⓑ

Exercise \(\PageIndex{33}\)

Locate on the number line: ⓐ 0.90.9 ⓑ −0.75.−0.75.

- Answer

-

ⓐ

ⓑ

Access this online resource for additional instruction and practice with decimals.

- Arithmetic Basics: Dividing Decimals

Key Concepts

- How to round decimals.

- Locate the given place value and mark it with an arrow.

- Underline the digit to the right of the place value.

- Is the underlined digit greater than or equal to 5?

- Yes: add 1 to the digit in the given place value.

- No: do not change the digit in the given place value

- Rewrite the number, deleting all digits to the right of the rounding digit.

- How to add or subtract decimals.

- Determine the sign of the sum or difference.

- Write the numbers so the decimal points line up vertically.

- Use zeros as placeholders, as needed.

- Add or subtract the numbers as if they were whole numbers. Then place the decimal point in the answer under the decimal points in the given numbers.

- Write the sum or difference with the appropriate sign

- How to multiply decimals.

- Determine the sign of the product.

- Write in vertical format, lining up the numbers on the right. Multiply the numbers as if they were whole numbers, temporarily ignoring the decimal points.

- Place the decimal point. The number of decimal places in the product is the sum of the number of decimal places in the factors.

- Write the product with the appropriate sign.

- How to multiply a decimal by a power of ten.

- Move the decimal point to the right the same number of places as the number of zeros in the power of 10.

- Add zeros at the end of the number as needed.

- How to divide decimals.

- Determine the sign of the quotient.

- Make the divisor a whole number by “moving” the decimal point all the way to the right. “Move” the decimal point in the dividend the same number of places—adding zeros as needed.

- Divide. Place the decimal point in the quotient above the decimal point in the dividend.

- Write the quotient with the appropriate sign.

- How to convert a decimal to a proper fraction and a fraction to a decimal.

- To convert a decimal to a proper fraction, determine the place value of the final digit.

- Write the fraction.

- numerator—the “numbers” to the right of the decimal point

- denominator—the place value corresponding to the final digit

- To convert a fraction to a decimal, divide the numerator of the fraction by the denominator of the fraction.

- How to convert a percent to a decimal and a decimal to a percent.

- To convert a percent to a decimal, move the decimal point two places to the left after removing the percent sign.

- To convert a decimal to a percent, move the decimal point two places to the right and then add the percent sign.

- Square Root Notation \(\sqrt{m}\) is read “the square root of m.” If \(m=n^2\), then \(\sqrt{m}=n\), for \(n≥0\). The square root of m, \(\sqrt{m}\), is the positive number whose square is m.

- Rational or Irrational If the decimal form of a number

- repeats or stops, the number is a rational number.

- does not repeat and does not stop, the number is an irrational number.

- Real Numbers

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=381&height=365)

Figure 4.

Glossary

- irrational number

- An irrational number is a number that cannot be written as the ratio of two integers. Its decimal form does not stop and does not repeat.

- percent

- A percent is a ratio whose denominator is 100.

- principal square root

- The positive square root is called the principal square root.

- rational number

- A rational number is a number of the form \(\frac{p}{q}\), where p and q are integers and \(q≠0\). Its decimal form stops or repeats.

- real number

- A real number is a number that is either rational or irrational.

- square of a number

- If \(n^2=m\), then m is the square of n.

- square root of a number

- If \(n^2=m\), then n is a square root of m.