1.12: Test-Taking Strategy Specifics

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 87070

Dave Dillon

“By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.”

– Benjamin Franklin

Discipline, Preparation and Execution

From what I have seen in my own educational experiences, along with coaching and teaching at the college and university level for over 20 years, test taking (with few exceptions) comes down to discipline, preparation and execution. Students wanting to be successful have to have the self-discipline to schedule time to study well in advance of the exam. They have to actually do the work: the preparation needed in order to have the best opportunity for success on the exam. Then they must execute: they have to be able to apply their preparation accordingly and perform well on the exam.

Preparation for an exam is not glamorous. It’s easy to find other things to do that are more interesting and fun. Students need to keep themselves motivated with their “eyes on the prize.” Think of it like this: if the most important event of your life was coming up and you wanted to perform to the best of your ability in that event, you would likely spend some time preparing for it, rehearsing for it, practicing it, etc. A student may argue that an exam they will be taking would not be the most important event of their life, but think back to the chapter on Passion. If you’re already spending the time, effort, energy and money to attend college, why not do it to the best of your ability?

It would be beneficial to spread this preparation and practice out over time and prepare periodically rather than to wait until the last minute and binge study or cram. Your preparation would not be the same and this may affect your test score. Binge studying and cramming also are not healthy. Staying up late puts stress on our brain and body, and not getting adequate sleep places our bodies at risk for getting sick.

“One of the most important keys to success is having the discipline to do what you know you should do, even when you don’t feel like doing it.”

– Unknown

“The will to succeed is important, but what’s more important is the will to prepare.”

– Bobby Knight

Everyone wants to be successful. When the exam is passed out, everyone wants to perform well. But what often separates successful students and less successful students is the preparation time put in.

Studying the right thing is a process and a skill. As you gain more experience, you will learn how to become better at knowing what to study. It can be very frustrating to spend a lot of time preparing and studying and then finding out that what you studied was not on the exam. You will see a lot of variance with exams due to different instructors, classes and types of tests. The better you become at predicting what will be on the exam and study accordingly, the better you will perform on your exams. Try placing yourself in your instructor’s shoes and design questions you think your instructor would ask. It’s often an eye-opening experience for students and a great study strategy.

Preparation for Exam Strategies

Find out as much about the exam in advance as you can.

Some professors will tell you how many questions there will be, what format the exam will be in, how much time you will have, etc., and others will not. I encourage students to ask questions about the exam if there is not information given. I also encourage students to ask those questions before class, after class, in professors’ office hours or via e-mail rather than during class.

Know the test

If you know how many questions, what the format is, and/or how much time you will have, you can start to mentally prepare for the exam much more so than if you are coming in with no information. There are two more important aspects that you may or may not know: a) what will be covered or asked on the exam; b) how the exam will be scored. Obviously, the more you know about what will be covered, the easier it is for you to be able to prepare for the exam. Most exam scoring is standardized, but not always.

Look for opportunities where some areas of the exam are worth more points than others. For example: An exam consists of 21 questions, with 10 being True/False, 10 being multiple choice, and one essay question. The T/F questions are worth 1 point each (10 points), the multiple-choice questions are worth 2 points each (20 points), and the essay question is worth 30 points. We know that the essay question is the most valuable (it is worth half of the value of the exam). And we should allocate our time for it accordingly. I would advise starting with the essay question. Do a quick analysis of time to be able to spend your time on the exam wisely. You want to spend some time with the exam question since it is so valuable, without sacrificing adequate time to ensure the T/F and multiple-choice questions are answered.

Often, the order of the exam in this scenario will be: T/F first, multiple choice second and essay third. Most students will go in the chronological order of the exam, but a savvy student would start with the essay. If an exam were to last for 30 minutes with this format of questions, I might recommend a student spent 15 minutes on the essay question, ten minutes on the multiple choice, three minutes on the T/F and two minutes reviewing their answer.

Also, look for situations where exams penalize students for incorrectly answering a question. This does not occur very often, but is the case with some exams. With the SAT for example, students are awarded one point for a correct answer and ¼ of a point subtracted for an incorrect answer. Points are not awarded nor subtracted for leaving a question blank. Thus, the strategy for a multiple-choice question is: if you can narrow down the potentially correct answer to two rather than four or five, it is statistically advantageous to answer the question and guess between the two answers; however, if a student had no idea if any of the answers were correct or incorrect, it would be best to leave the answer blank. Remember, this is rare, but it is important to understand the strategy when students take these exams.

In conclusion, the more information you have about the exam, the better you can prepare for content, allocation of time spent on aspects of the exam, and the more confident you will be in knowing how and when to attempt to answer questions.

Take care of your body

Before the exam, it is important to prepare your brain and body for optimal performance for your exam. Do not cram the night before. Get a good night’s sleep. Make sure you eat (nutritiously) before the exam. I recommend exercising the day before and if possible a few hours before the exam.

Strategies for Specific Exam Formats

True or False Questions

Look for qualifiers. A qualifier is a word that is absolute. Examples are: all, never, no, always, none, every, only, entirely. They are often seen in false statements. This is because it is more difficult to create a true statement using a qualifier like never, no, always, etc. For example, “All cats chase mice.” Cats may be known for chasing mice, but not all of them do so. The answer here is false and the qualifier “all” gave us a tip. Qualifiers such as: sometimes, many, some, most, often, and usually are commonly found in true statements. For example: “Most cats chase mice.” This is true and the qualifier “most” gave us a tip.

Make sure to read the entire statement. All parts of a sentence must be true if the whole statement is to be true. If one part of it is false, the whole sentence is false. Long sentences are often false for this reason.

Students should guess on True or False questions they do not know the answer to unless there is a penalty for an incorrect answer.

Multiple Choice Questions

Think of multiple choice questions as four (or five) true or false statements in one. One of the statements is true (the correct answer) and the others will be false. Apply the same strategy toward qualifiers. If you see an absolute qualifier in one of the answer choices, it is probably false and not the correct answer. Try to identify the true statement. If you can do this, you have the answer as there is only one. If you cannot do this at first, try eliminating answers you know to be false.

If there is no penalty for incorrect answers, my suggestion is to guess if you are not certain of the answer. If there is a penalty for incorrect answers, common logic is to guess if you can eliminate two of the answers as incorrect (pending what the penalty is). If there’s a penalty and you cannot narrow down the answers, it’s best to leave it blank. You may wish to ask your instructor for clarification.

Answers that are strange and unrelated to the question are usually false. If two answers have a word that looks or sounds similar, one of those is usually correct. For example: abductor/ adductor. If you see these as two of the four or five choices, one of them is usually correct. Also look for answers that are grammatically incorrect. These are usually incorrect answers. If you have to completely guess, choose B or C. It is statistically proven to be correct more than 25 percent of the time. If there are four answers for each question, and an exam had standardized the answers, each answer on the exam A, B, C and D would be equal. But most instructors do not standardize their answers, and more correct answers are found in the middle (B and C then the extremes A and D or E). “People writing isolated four-choice questions hide the correct answer in the two middle positions about 70% of the time.”[1] This is 20 percent more correct answers found in B or C than a standardized exam with equal correct answers for each letter.

Matching Questions

Although less common than the other types of exams, you will likely see some matching exams during your time in college. First, read the instructions and take a look at both lists to determine what the items are and their relationship. It is especially important to determine if both lists have the same number of items and if all items are to be used, and used only once.

Matching exams become much more difficult if one list has more items than the other or if items either might not be used or could be used more than once. If your exam instructions do not discern this, you may wish to ask your instructor for further clarification. I advise students to take a look at the whole list before selecting an answer because a more correct answer may be found further into the list. Mark items when you are sure you have a match (pending the number of items in the list this may eliminate answers for the future). Guessing (if needed) should take place once you have selected answers you are certain about.

Short-Answer Questions

Read all of the instructions first. Budget your time and then read all of the questions. Answer the ones you know best or feel the most confident with. Then go back to the other ones. If you do not know the answer and there is no penalty for incorrect answers, guess. Use common sense. Sometimes instructors will award partial credit for a logical answer that is related even if it is not the correct answer.

Essay Questions

Keep in mind that knowing the format of the exam can help you determine how to study. If I know that I am taking a True-False exam, I know that I will need to discern whether a statement is True or False. I will need to know subject content for the course. But if I am studying for short answer and especially for essay questions, I must know a lot more. For essay questions, I must have much greater content knowledge and be able to make a coherent argument that answers the question using information from textbooks, lectures or other course materials. I have to place a lot more time and thought into studying for an essay exam than for True-False or Multiple-Choice exams.

Read the essay question(s) and the instructions first. Plan your time wisely and organize your answer before you start to write. Address the answer to the question in your first or second sentence. It may help to restate the original question. Write clearly and legibly. Instructors have difficulty grading essays that they cannot read. Save some time for review when you have finished writing to check spelling, grammar and coherent thought in your answer. Make sure you have addressed all parts of the essay question.

During the Exam:

Always read the directions first. Read them thoroughly.

Preview the exam to help you allocate proper time for each area.

Skip questions if you do not know the answer but make a mark somewhere to ensure you are able to go back to those questions (you may need to reallocate your prepared time for this depending on how many there are).

Allocate some time to review your answers before submitting your exam or the exam time expiring.

One of the biggest mistakes that students make after they take an exam in a course is that they do not use the exam for the future. The exam contains a lot of information that can be helpful in studying for future exams. Students that perform well on an exam often put it away thinking they do not need it anymore. Students who do poorly on an exam often put it away, not wanting to think about it any further.

In both cases, students are missing out on the value of reviewing their exams. It is wise to review exams for three reasons: 1) students should review the answers that were correct because they may see those questions on future exams and it is important to reinforce learning; 2) students should review the answers that were incorrect in order to learn what the correct answer was and why. These questions also may appear on a future exam. In addition, occasionally an answer is marked incorrect, when it should have been marked correct. The student would never know this if they didn’t review their exam; and 3) there is value in reviewing the exam to try to predict what questions or what format will be used by a professor for a future exam in the same course.

Author’s Story

What does it mean to be a “poor test taker?” Think about that. Does it mean that the student has put effort into studying but has difficulty under pressure? Does it mean that a student studies the wrong material? Is the student prepared but does not execute well? Could the student have a learning disability? Are they missing key strategies for taking tests? It could mean any of those things. And while I believe that it may be true that a student may be a “poor test taker,” it does not by any means mean it is permanent. Students willing to work hard and learn can improve their test taking skills and raise their confidence.

In high school chemistry, I earned a D grade. In microeconomics at UC Santa Cruz, I struggled and barely passed. Both of these classes had grading systems that were heavily weighted by exams. I was an above average student in my other classes in both high school and college, and so I was told (and believed for a long time) that I was not a “good test taker.” I no longer believe this. I will not make excuses. The responsibility for the grade I earned rests solely with me. I mention this because many students come to my office and complain that their professor grades in a way that is unfair to them because so much emphasis is on exams and that they understand the material but are “not good test takers.” It may be the case that my grade or another students’ grade would have been better had the course grade been determined with less weight levied to exams. That to me is irrelevant. It does not absolve me from being responsible for knowing what the grading metrics were at the beginning of the course and choosing to continue in the course after learning this knowledge. In the end, I realized I was not a poor test taker and that I needed to spend more time studying and preparing to perform well on exams. I changed my attitude from being afraid of exams to one of believing I was going to do well regardless of the class or the format of the exam. Once I had confidence that I had the necessary tools and was willing to work hard, it changed my entire perspective and experience with exams.

Note: if you think you may have a learning disability and would like to get assessed, contact your college to see what steps to follow to begin the assessment process.

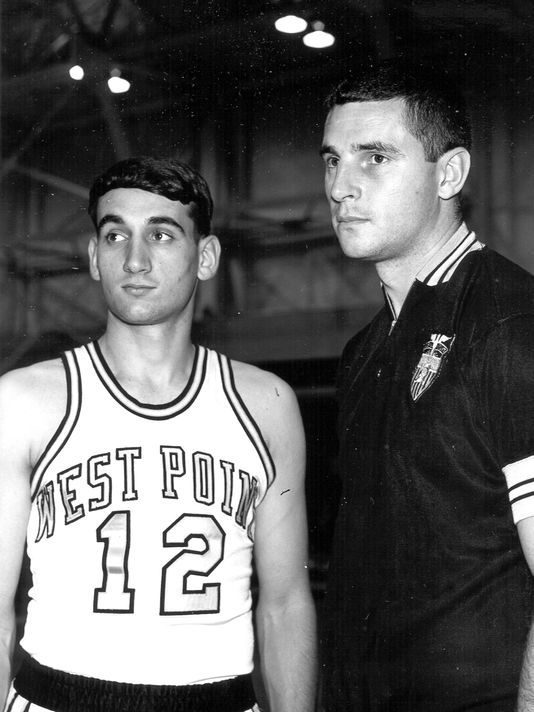

Thinking about excuses reminds me of a story about Mike Krzyzewski, the successful Duke University men’s basketball coach. Before Krzyzewski coached, he was a student at the United States Military Academy at West Point. One day in his first year, Krzyzweski and his roommate were walking and his roommate stepped in a puddle. Mud splashed onto Krzyzewski’s uniform. Immediately, an upperclassman screamed at Krzyzewski about not knowing the rules of wearing a clean uniform. Plebes (first-year students at military academies) are allowed three answers when asked a question: “Yes sir!” “No sir!” And “No excuse sir!” Krzyzewski repeated himself, “No excuse sir!” Despite wanting to explain what had happened and that it was not his fault, he realized that there was no excuse. It was his responsibility to keep a clean uniform.

Licenses and Attributions:

Content previously copyrighted, published in Blueprint for Success in College: Indispensable Study Skills and Time Management Strategies (by Dave Dillon), now licensed as CC BY Attribution.

- Yigal Attali and Maya Bar-Hillel, “Guess Where: The Position of Correct Answers in Multiple-Choice Test Items as a Psychometric Variable,” Journal of Educational Measurement 40 no. 2 (2003):109-128. ↵