5.6: Second order systems and applications

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Undamped Mass-Spring Systems

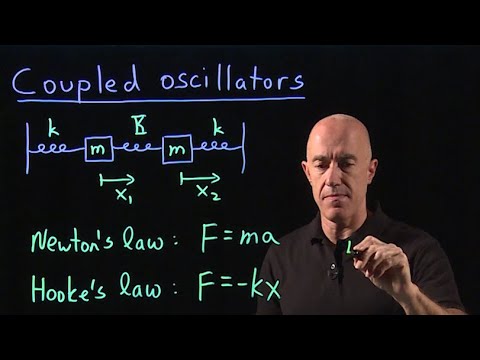

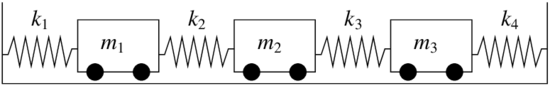

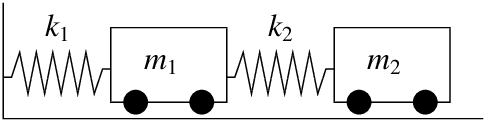

While we did say that we will usually only look at first order systems, it is sometimes more convenient to study the system in the way it arises naturally. For example, suppose we have 3 masses connected by springs between two walls. We could pick any higher number, and the math would be essentially the same, but for simplicity we pick 3 right now. Let us also assume no friction, that is, the system is undamped. The masses are m1,m2, and m3 and the spring constants are k1,k2,k3, and k4. Let x1 be the displacement from rest position of the first mass, and x2 and x3 the displacement of the second and third mass. We will make, as usual, positive values go right (as x1 grows, the first mass is moving right). See Figure 5.6.1.

This simple system turns up in unexpected places. For example, our world really consists of many small particles of matter interacting together. When we try the above system with many more masses, we obtain a good approximation to how an elastic material behaves. By somehow taking a limit of the number of masses going to infinity, we obtain the continuous one dimensional wave equation (that we study in Section 4.7). But we digress.

Let us set up the equations for the three mass system. By Hooke’s law we have that the force acting on the mass equals the spring compression times the spring constant. By Newton’s second law we have that force is mass times acceleration. So if we sum the forces acting on each mass and put the right sign in front of each term, depending on the direction in which it is acting, we end up with the desired system of equations.

m1x″1=−k1x1+k2(x2−x1)=−(k1+k2)x1+k2x2,m2x″2=−k2(x2−x1)+k3(x3−x2)=k2x1−(k2+k3)x2+k3x3,m3x″3=−k3(x3−x2)−k4x3=k3x2−(k3+k4)x3.

We define the matrices

M=[m1000m2000m3] and K=[−(k1+k2)k20k2−(k2+k3)k30k3−(k3+k4)].

We write the equation simply as

M→x″=K→x.

At this point we could introduce 3 new variables and write out a system of 6 first order equations. We claim this simple setup is easier to handle as a second order system. We call →x the displacement vector, M the mass matrix, and K the stiffness matrix.

Repeat this setup for 4 masses (find the matrices M and K). Do it for 5 masses. Can you find a prescription to do it for n masses?

As with a single equation we want to “divide by M.” This means computing the inverse of M. The masses are all nonzero and Mis a diagonal matrix, so comping the inverse is easy:

M−1=[1m10001m20001m3].

This fact follows readily by how we multiply diagonal matrices. As an exercise, you should verify that MM−1=M−1M=I.

Let A=M−1K. We look at the system →x″=M−1K→x, or

→x″=A→x.

Many real world systems can be modeled by this equation. For simplicity, we will only talk about the given masses-and-springs problem. We try a solution of the form

→x=→veαt.

We compute that for this guess, →x″=α2→veαt. We plug our guess into the equation and get

α2→veαt=A→veαt.

We divide by eαt to arrive at α2→v=A→v. Hence if α2 is an eigenvalue of A and →v is a corresponding eigenvector, we have found a solution.

In our example, and in other common applications, A has only real negative eigenvalues (and possibly a zero eigenvalue). So we study only this case. When an eigenvalue λ is negative, it means that α2=λ is negative. Hence there is some real number ω such that −ω2=λ. Then α=±iω. The solution we guessed was

→x=→v(cos(ωt)+isin(ωt)).

By taking the real and imaginary parts (note that →v is real), we find that →vcos(ωt) and →vsin(ωt) are linearly independent solutions.

If an eigenvalue is zero, it turns out that both →v and →vt are solutions, where →v is an eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue 0.

Show that if A has a zero eigenvalue and →v is a corresponding eigenvector, then →x=→v(a+bt) is a solution of →x″=A→x for arbitrary constants a and b.

Let A be an n×n matrix with n distinct real negative eigenvalues we denote by −ω21>−ω22>⋯>−ω2n, and corresponding eigenvectors by →v1,→v2,…,→vn. If A is invertible (that is, if ω1>0), then

→x(t)=n∑i=1→vi(aicos(ωit)+bisin(ωit)),

is the general solution of

→x″=A→x,

for some arbitrary constants ai and bi. If A has a zero eigenvalue, that is ω1=0, and all other eigenvalues are distinct and negative, then the general solution can be written as

→x(t)=→v1(a1+b1t)+n∑i=2→vi(aicos(ωit)+bisin(ωit)).

We use this solution and the setup from the introduction of this section even when some of the masses and springs are missing. For example, when there are only 2 masses and only 2 springs, simply take only the equations for the two masses and set all the spring constants for the springs that are missing to zero.

Suppose we have the system in Figure 5.6.2, with m1=2,m2=1,k1=4, and k2=2.

The equations we write down are

[2001]→x″=[−(4+2)22−2]→x,

or

→x″=[−312−2]→x.

We find the eigenvalues of A to be λ=−1,−4 (exercise). We find corresponding eigenvectors to be [12] and [1−1] respectively (exercise).

We check the theorem and note that ω1=1 and ω2=2. Hence the general solution is

→x=[12](a1cos(t)+b1sin(t))+[1−1](a2cos(2t)+b2sin(2t)).

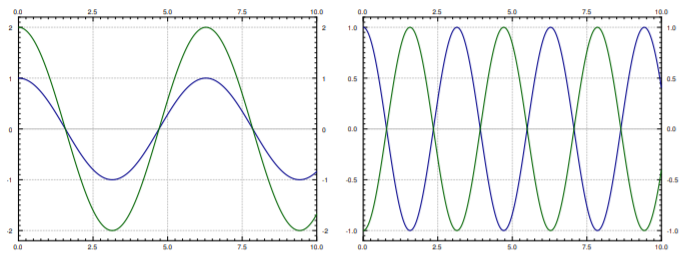

The two terms in the solution represent the two so-called natural or normal modes of oscillation. And the two (angular) frequencies are the natural frequencies. The first natural frequency is 1, and second natural frequency is 2. The two modes are plotted in Figure 5.6.3.

Let us write the solution as

→x=[12]c1cos(t−α1)+[1−1]c2cos(2t−α2).

The first term,

[12]c1cos(t−α1)=[c1cos(t−α1)2c1cos(t−α1)],

corresponds to the mode where the masses move synchronously in the same direction.

The second term,

[1−1]c2cos(2t−α2)=[c2cos(2t−α2)−c2cos(2t−α2)],

corresponds to the mode where the masses move synchronously but in opposite directions.

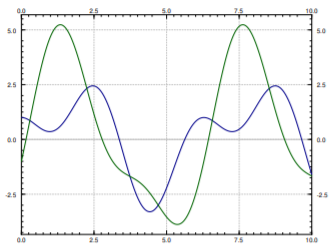

The general solution is a combination of the two modes. That is, the initial conditions determine the amplitude and phase shift of each mode. As an example, suppose we have initial conditions

→x(0)=[1−1],→x′(0)=[06].

We use the aj,bj constants to solve for initial conditions. First

[1−1]=→x(0)=[12]a1+[1−1]a2=[a1+a22a1−a2].

We solve (exercise) to find a1=0, a2=1. To find the b1 and b2, we differentiate first: →x′=[12](−a1sin(t)+b1cos(t))+[1−1](−2a2sin(2t)+2b2cos(2t)).

Now we solve: [06]=→x′(0)=[12]b1+[1−1]2b2=[b1+2b22b1−2b2].

Again solve (exercise) to find b1=2, b2=−1. So our solution is →x=[12]2sin(t)+[1−1](cos(2t)−sin(2t))=[2sin(t)+cos(2t)−sin(2t)4sin(t)−cos(2t)+sin(2t)].

The graphs of the two displacements, x1 and x2 of the two carts is in Figure 5.6.4.

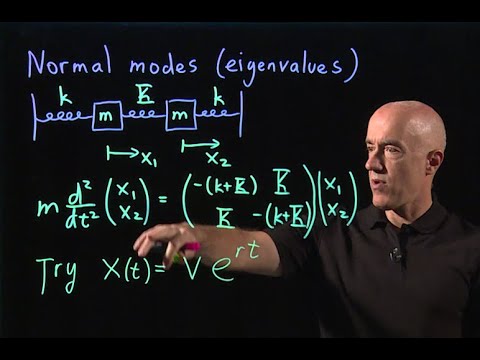

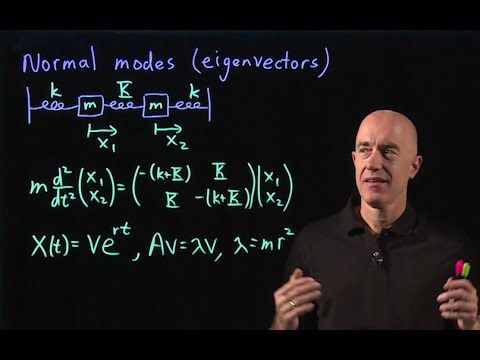

Below is a video on coupled oscillators.

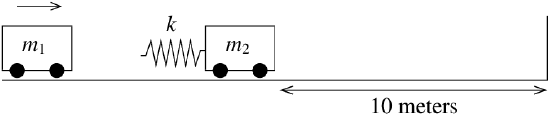

We have two toy rail cars. Car 1 of mass 2 kg is traveling at 3ms towards the second rail car of mass 1 kg. There is a bumper on the second rail car that engages at the moment the cars hit (it connects to two cars) and does not let go. The bumper acts like a spring of spring constant k=2Nm. The second car is 10 meters from a wall. See Figure 5.6.5.

We want to ask several questions. At what time after the cars link does impact with the wall happen? What is the speed of car 2 when it hits the wall?

OK, let us first set the system up. Let t=0 be the time when the two cars link up. Let x1 be the displacement of the first car from the position at t=0, and let x2 be the displacement of the second car from its original location. Then the time when x2(t)=10 is exactly the time when impact with wall occurs. For this t,x′2(t) is the speed at impact. This system acts just like the system of the previous example but without k1. Hence the equation is

[2001]→x″=[−222−2]→x.

or

→x″=[−112−2]→x.

We compute the eigenvalues of A. It is not hard to see that the eigenvalues are 0 and −3 (exercise). Furthermore, eigenvectors are [11] and [1−2] respectively (exercise). Then ω2=√3 and by the second part of the theorem we find our general solution to be

→x=[11](a1+b1t)+[1−2](a2cos(√3t)+b2sin(√3t))=[a1+b1t+a2cos(√3t)+b2sin(√3t)a1+b1t−2a2cos(√3t)−2b2sin(√3t)]

We now apply the initial conditions. First the cars start at position 0 so x1(0)=0 and x2(0)=0. The first car is traveling at 3ms, so x′1(0)=3 and the second car starts at rest, so x′2(0)=0. The first conditions says

→0=→x(0)=[a1+a2a1−2a2].

It is not hard to see that a1=a2=0. We set a1=0 and a2=0 in →x(t) and differentiate to get

→x′(t)=[b1+√3b2cos(√3t)b1−2√3b2cos(√3t)].

So

[30]=→x′(0)=[b1+√3b2b1−2√3b2].

Solving these two equations we find b1=2 and b2=1√3. Hence the position of our cars is (until the impact with the wall)

→x=[2t+1√3sin(√3t)2t−2√3sin(√3t)].

Note how the presence of the zero eigenvalue resulted in a term containing t. This means that the carts will be traveling in the positive direction as time grows, which is what we expect.

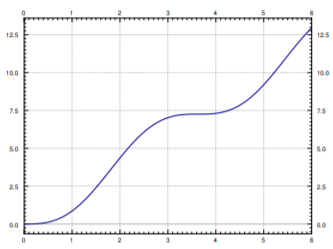

What we are really interested in is the second expression, the one for x2. We have x2(t)=2t−2√3sin(√3t). See Figure 5.6.6 for the plot of x2 versus time.

Just from the graph we can see that time of impact will be a little more than 5 seconds from time zero. For this we have to solve the equation 10=x2(t)=2t−2√3sin(√3t). Using a computer (or even a graphing calculator) we find that timpact≈5.22 seconds.

As for the speed we note that x′2=2−2cos(√3t). At time of impact (5.22 seconds from t=0) we get that x′2(timpact)≈3.85.

The maximum speed is the maximum of 2−2cos(√3t), which is 4. We are traveling at almost the maximum speed when we hit the wall.

Suppose that Tiana is a tiny person sitting on car 2. Tiana has a Martini in her hand and would like not to spill it. Let us suppose Tiana would not spill her Martini when the first car links up with car 2, but if car 2 hits the wall at any speed greater than zero, Tiana will spill her drink. Suppose Tiana can move car 2 a few meters towards or away from the wall (he cannot go all the way to the wall, nor can she get out of the way of the first car). Is there a “safe” distance for her to be at? A distance such that the impact with the wall is at zero speed?

The answer is yes. Looking at Figure 5.6.6, we note the “plateau” between t=3 and t=4. There is a point where the speed is zero. To find it we need to solve x′2(t)=0. This is when cos(√3t)=1 or in other words when t=2π√3,4π√3,… and so on. We plug in the first value to obtain x2(2π√3)=4π√3≈7.26. So a “safe” distance is about 7 and a quarter meters from the wall.

Alternatively Tiana could move away from the wall towards the incoming car 2 where another safe distance is 8π√3≈14.51 and so on, using all the different t such that x′2(t)=0. Of course t=0 is always a solution here, corresponding to x2=0, but that means standing right at the wall.

Below is a video on normal modes.

Below is another video on normal modes.

Forced Oscillations

Finally we move to forced oscillations. Suppose that now our system is

→x″=A→x+→Fcos(ωt).

That is, we are adding periodic forcing to the system in the direction of the vector →F.

As before, this system just requires us to find one particular solution →xp, add it to the general solution of the associated homogeneous system →xc, and we will have the general solution to (???). Let us suppose that ω is not one of the natural frequencies of →x″=A→x, then we can guess

→xp=→ccos(ωt),

where →c is an unknown constant vector. Note that we do not need to use sine since there are only second derivatives. We solve for →c to find →xp. This is really just the method of undetermined coefficients for systems. Let us differentiate →xp twice to get

→x″p=−ω2→ccos(ωt).

Plug →xp and →x″p into the equation (???):

→xp″⏞−ω2→ccos(ωt)=A→xp⏞A→ccos(ωt)+→Fcos(ωt).

We cancel out the cosine and rearrange the equation to obtain

(A+ω2I)→c=−→F.

So

→c=(A+ω2I)−1(−→F).

Of course this is possible only if (A+ω2I)=(A−(−ω2)I) is invertible. That matrix is invertible if and only if −ω2 is not an eigenvalue of A. That is true if and only if ω is not a natural frequency of the system.

We simplified things a little bit. If we wish to have the forcing term to be in the units of force, say Newtons, then we must write M→x″=K→x+→Gcos(ωt).

If we then write things in terms of A=M−1K, we have →x″=M−1K→x+M−1→Gcos(ωt)or→x″=A→x+→Fcos(ωt),

where →F=M−1→G.

Let us take the example in Figure 5.6.2 with the same parameters as before: m1=2,m2=1,k1=4, and k2=2. Now suppose that there is a force 2cos(3t) acting on the second cart.

The equation is

[2001]→x″=[−422−2]→x+[02]cos(3t)or→x″=[−312−2]→x+[02]cos(3t).

We solved the associated homogeneous equation before and found the complementary solution to be

→xc=[12](a1cos(t)+b1sin(t))+[1−1](a2cos(2t)+b2sin(2t)).

The natural frequencies are 1 and 2. Hence as 3 is not a natural frequency, we can try →ccos(3t). We invert (A+32I):

([−312−2]+32I)−1=[6127]−1=[740−140−120320].

Hence,

→c=(A+ω2I)−1(−→F)=[740−140−120320][0−2]=[120−310].

Combining with what we know the general solution of the associated homogeneous problem to be, we get that the general solution to →x″=A→x+→Fcos(ωt) is

→x=→xc+→xp=[12](a1cos(t)+b1sin(t))+[1−1](a2cos(2t)+b2sin(2t))+[120−310]cos(3t).

The constants a1,a2,b1, and b2 must then be solved for given any initial conditions.

Note that given force →f, we write the equation as M→x″=K→x+→f to get the units right. Then we write →x″=M−1K→x+M−1→f. The term →g=M−1→f in →x″=A→x+→g is in units of force per unit mass.

If ω is a natural frequency of the system resonance occurs because we will have to try a particular solution of the form

→xp=→ctsin(ωt)+→dtcos(ωt).

That is assuming that the eigenvalues of the coefficient matrix are distinct. Next, note that the amplitude of this solution grows without bound as t grows.