16.3: Graphs of Functions

- Page ID

- 46404

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Use the vertical line test

- Identify graphs of basic functions

- Read information from a graph of a function

Before you get started, take this readiness quiz.

Use the Vertical Line Test

In the last section we learned how to determine if a relation is a function. The relations we looked at were expressed as a set of ordered pairs, a mapping or an equation. We will now look at how to tell if a graph is that of a function.

An ordered pair \((x,y)\) is a solution of a linear equation, if the equation is a true statement when the x- and y-values of the ordered pair are substituted into the equation.

The graph of a linear equation is a straight line where every point on the line is a solution of the equation and every solution of this equation is a point on this line.

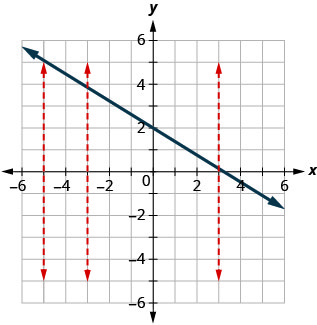

In Figure, we can see that, in graph of the equation \(y=2x−3\), for every x-value there is only one y-value, as shown in the accompanying table.

A relation is a function if every element of the domain has exactly one value in the range. So the relation defined by the equation \(y=2x−3\) is a function.

If we look at the graph, each vertical dashed line only intersects the line at one point. This makes sense as in a function, for every x-value there is only one y-value.

If the vertical line hit the graph twice, the x-value would be mapped to two y-values, and so the graph would not represent a function.

This leads us to the vertical line test. A set of points in a rectangular coordinate system is the graph of a function if every vertical line intersects the graph in at most one point. If any vertical line intersects the graph in more than one point, the graph does not represent a function.

VERTICAL LINE TEST

A set of points in a rectangular coordinate system is the graph of a function if every vertical line intersects the graph in at most one point.

If any vertical line intersects the graph in more than one point, the graph does not represent a function.

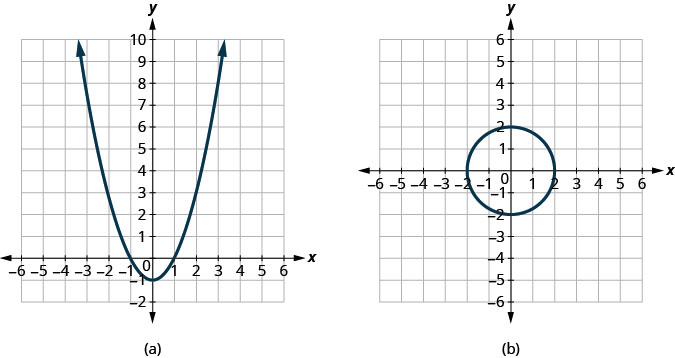

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Determine whether each graph is the graph of a function.

- Answer

-

ⓐ Since any vertical line intersects the graph in at most one point, the graph is the graph of a function.

ⓑ One of the vertical lines shown on the graph, intersects it in two points. This graph does not represent a function.

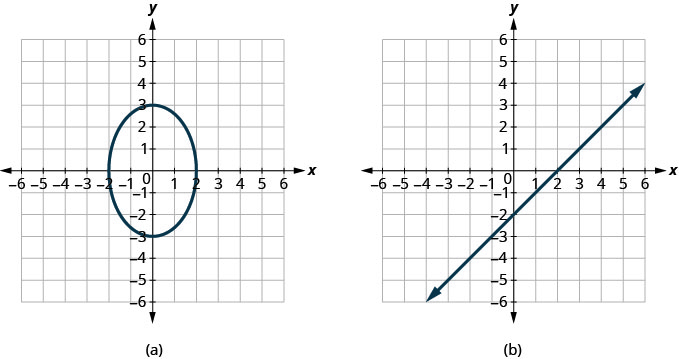

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Determine whether each graph is the graph of a function.

- Answer

-

ⓐ yes ⓑ no

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Determine whether each graph is the graph of a function.

- Answer

-

ⓐ no ⓑ yes

Identify Graphs of Basic Functions

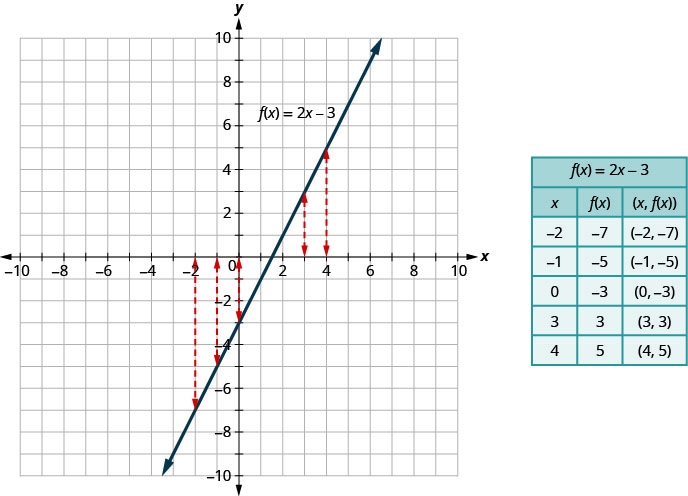

We used the equation \(y=2x−3\) and its graph as we developed the vertical line test. We said that the relation defined by the equation \(y=2x−3\) is a function.

We can write this as in function notation as \(f(x)=2x−3\). It still means the same thing. The graph of the function is the graph of all ordered pairs \((x,y)\) where \(y=f(x)\). So we can write the ordered pairs as \((x,f(x))\). It looks different but the graph will be the same.

Compare the graph of \(y=2x−3\) previously shown in Figure with the graph of \(f(x)=2x−3\) shown in Figure. Nothing has changed but the notation.

GRAPH OF A FUNCTION

The graph of a function is the graph of all its ordered pairs, (x,y)(x,y) or using function notation, (x,f(x))(x,f(x)) where y=f(x).y=f(x).

\[\begin{array} {ll} {f} &{\text{name of function}} \\ {x} &{\text{x-coordinate of the ordered pair}} \\ {f(x)} &{\text{y-coordinate of the ordered pair}} \\ \nonumber \end{array}\]

As we move forward in our study, it is helpful to be familiar with the graphs of several basic functions and be able to identify them.

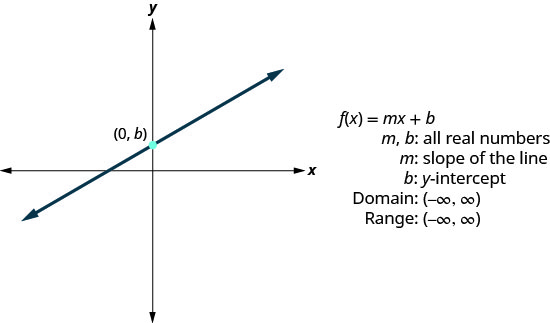

Through our earlier work, we are familiar with the graphs of linear equations. The process we used to decide if \(y=2x−3\) is a function would apply to all linear equations. All non-vertical linear equations are functions. Vertical lines are not functions as the x-value has infinitely many y-values.

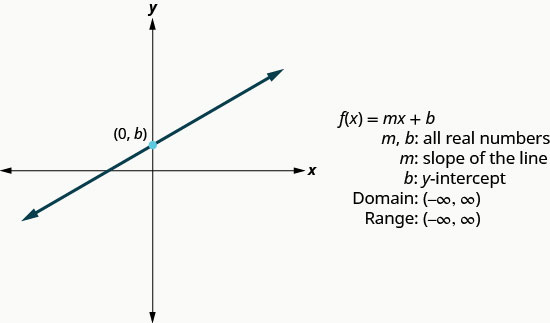

We wrote linear equations in several forms, but it will be most helpful for us here to use the slope-intercept form of the linear equation. The slope-intercept form of a linear equation is \(y=mx+b\). In function notation, this linear function becomes \(f(x)=mx+b\) where m is the slope of the line and b is the y-intercept.

The domain is the set of all real numbers, and the range is also the set of all real numbers.

LINEAR FUNCTION

We will use the graphing techniques we used earlier, to graph the basic functions.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

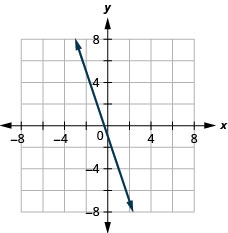

Graph: \(f(x)=−2x−4\).

- Answer

-

\(f(x)=−2x−4\) We recognize this as a linear function. Find the slope and y-intercept. \(m=−2\)

\(b=−4\)Graph using the slope intercept.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=−3x−1\)

- Answer

-

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=−4x−5\)

- Answer

-

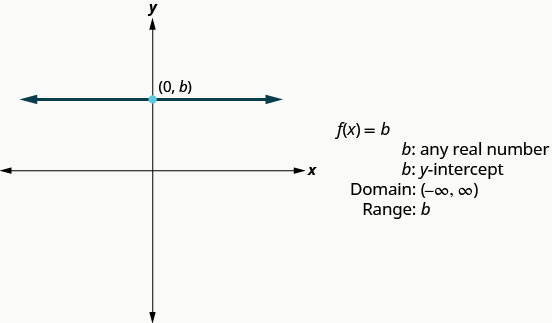

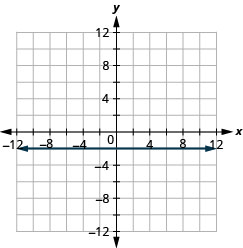

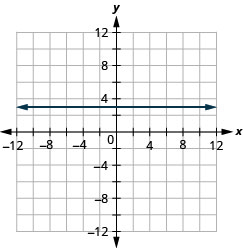

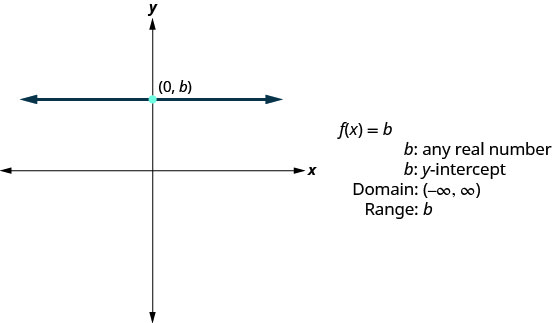

The next function whose graph we will look at is called the constant function and its equation is of the form \(f(x)=b\), where b is any real number. If we replace the \(f(x)\) with y, we get \(y=b\). We recognize this as the horizontal line whose y-intercept is b. The graph of the function \(f(x)=b\), is also the horizontal line whose y-intercept is b.

Notice that for any real number we put in the function, the function value will be b. This tells us the range has only one value, b.

CONSTANT FUNCTION

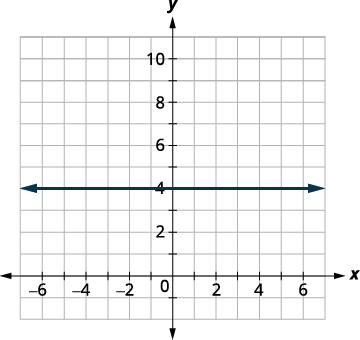

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=4\).

- Answer

-

\(f(x)=4\) We recognize this as a constant function. The graph will be a horizontal line through \((0,4)\).

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=−2\).

- Answer

-

Example \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=3\).

- Answer

-

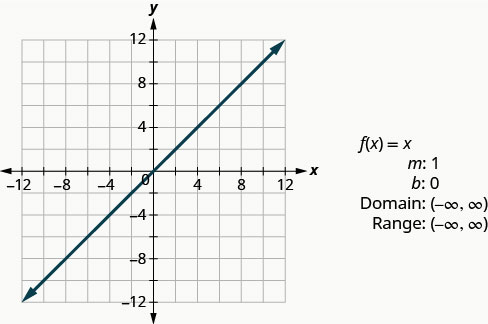

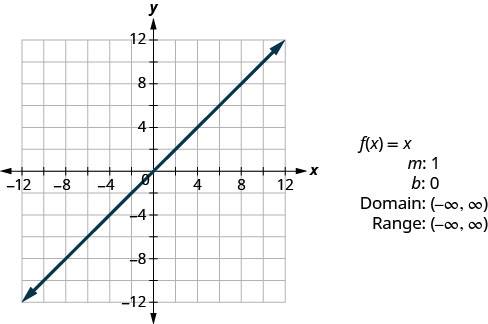

The identity function, \(f(x)=x\) is a special case of the linear function. If we write it in linear function form, \(f(x)=1x+0\), we see the slope is 1 and the y-intercept is 0.

IDENTITY FUNCTION

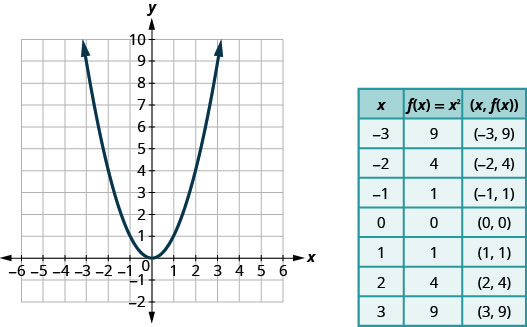

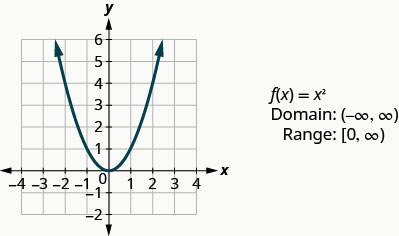

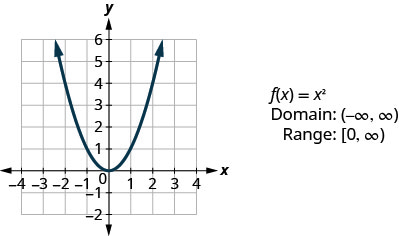

The next function we will look at is not a linear function. So the graph will not be a line. The only method we have to graph this function is point plotting. Because this is an unfamiliar function, we make sure to choose several positive and negative values as well as 0 for our x-values.

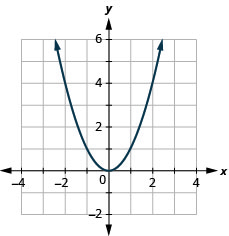

Graph: \(f(x)=x^2\).

- Answer

-

We choose x-values. We substitute them in and then create a chart as shown.

Example \(\PageIndex{11}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=x^2\).

- Answer

-

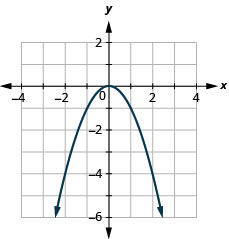

Example \(\PageIndex{12}\)

\(f(x)=−x^2\)

- Answer

-

Looking at the result in Example, we can summarize the features of the square function. We call this graph a parabola. As we consider the domain, notice any real number can be used as an x-value. The domain is all real numbers.

The range is not all real numbers. Notice the graph consists of values of y never go below zero. This makes sense as the square of any number cannot be negative. So, the range of the square function is all non-negative real numbers.

SQUARE FUNCTION

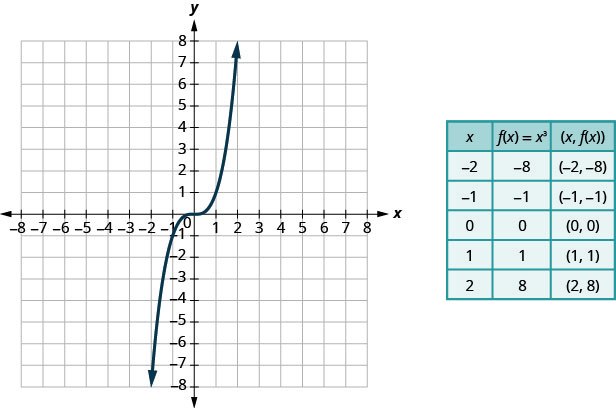

The next function we will look at is also not a linear function so the graph will not be a line. Again we will use point plotting, and make sure to choose several positive and negative values as well as 0 for our x-values.

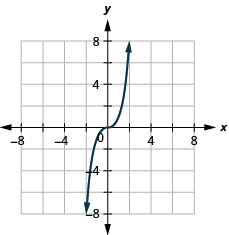

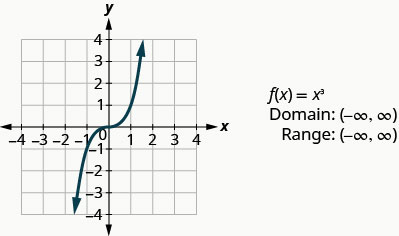

Graph: \(f(x)=x^3\).

- Answer

-

We choose x-values. We substitute them in and then create a chart.

Example \(\PageIndex{14}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=x^3\).

- Answer

-

Example \(\PageIndex{15}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=−x^3\).

- Answer

-

Looking at the result in Example, we can summarize the features of the cube function. As we consider the domain, notice any real number can be used as an x-value. The domain is all real numbers.

The range is all real numbers. This makes sense as the cube of any non-zero number can be positive or negative. So, the range of the cube function is all real numbers.

CUBE FUNCTION

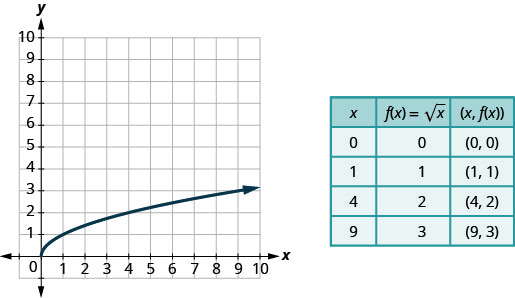

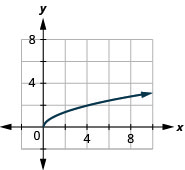

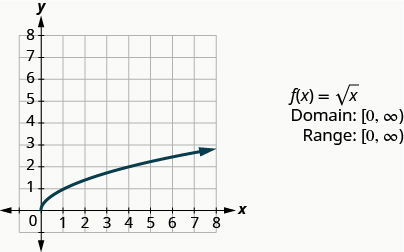

The next function we will look at does not square or cube the input values, but rather takes the square root of those values.

Let’s graph the function \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\) and then summarize the features of the function. Remember, we can only take the square root of non-negative real numbers, so our domain will be the non-negative real numbers.

Example \(\PageIndex{16}\)

\(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\)

- Answer

-

We choose x-values. Since we will be taking the square root, we choose numbers that are perfect squares, to make our work easier. We substitute them in and then create a chart.

Example \(\PageIndex{17}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=x\).

- Answer

-

Example \(\PageIndex{18}\)

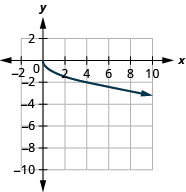

Graph: \(f(x)=−\sqrt{x}\).

- Answer

-

SQUARE ROOT FUNCTION

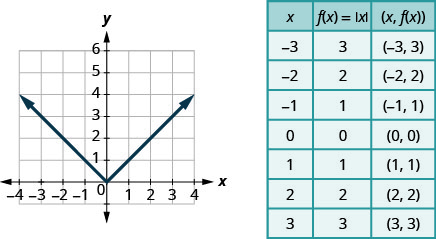

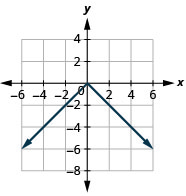

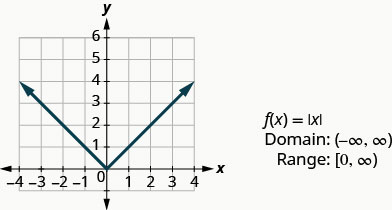

Our last basic function is the absolute value function, \(f(x)=|x|\). Keep in mind that the absolute value of a number is its distance from zero. Since we never measure distance as a negative number, we will never get a negative number in the range.

Graph: \(f(x)=|x|\).

- Answer

-

We choose x-values. We substitute them in and then create a chart.

Example \(\PageIndex{20}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=|x|\).

- Answer

-

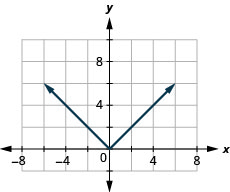

Example \(\PageIndex{21}\)

Graph: \(f(x)=−|x|\).

- Answer

-

ABSOLUTE VALUE FUNCTION

Read Information from a Graph of a Function

In the sciences and business, data is often collected and then graphed. The graph is analyzed, information is obtained from the graph and then often predictions are made from the data.

We will start by reading the domain and range of a function from its graph.

Remember the domain is the set of all the x-values in the ordered pairs in the function. To find the domain we look at the graph and find all the values of x that have a corresponding value on the graph. Follow the value x up or down vertically. If you hit the graph of the function then x is in the domain.

Remember the range is the set of all the y-values in the ordered pairs in the function. To find the range we look at the graph and find all the values of y that have a corresponding value on the graph. Follow the value y left or right horizontally. If you hit the graph of the function then y is in the range.

Example \(\PageIndex{22}\)

Use the graph of the function to find its domain and range. Write the domain and range in interval notation.

![This figure has a curved line segment graphed on the x y-coordinate plane. The x-axis runs from negative 4 to 4. The y-axis runs from negative 4 to 4. The curved line segment goes through the points (negative 3, negative 1), (1.5, 3), and (3, 1). The interval [negative 3, 3] is marked on the horizontal axis. The interval [negative 1, 3] is marked on the vertical axis.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/22958/CNX_IntAlg_Figure_03_06_021_img_new.jpg?revision=1)

- Answer

-

To find the domain we look at the graph and find all the values of x that correspond to a point on the graph. The domain is highlighted in red on the graph. The domain is \([−3,3]\).

To find the range we look at the graph and find all the values of y that correspond to a point on the graph. The range is highlighted in blue on the graph. The range is \([−1,3]\).

Example \(\PageIndex{23}\)

Use the graph of the function to find its domain and range. Write the domain and range in interval notation.

![This figure has a curved line segment graphed on the x y-coordinate plane. The x-axis runs from negative 6 to 6. The y-axis runs from negative 6 to 6. The curved line segment goes through the points (negative 5, negative 4), (0, negative 3), and (1, 2). The interval [negative 5, 1] is marked on the horizontal axis. The interval [negative 4, 2] is marked on the vertical axis.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/22776/CNX_IntAlg_Figure_03_06_022_img_new.jpg?revision=1)

- Answer

-

The domain is \([−5,1]\). The range is \([−4,2]\).

Example \(\PageIndex{24}\)

Use the graph of the function to find its domain and range. Write the domain and range in interval notation.

![This figure has a curved line segment graphed on the x y-coordinate plane. The x-axis runs from negative 4 to 5. The y-axis runs from negative 6 to 4. The curved line segment goes through the points (negative 2, 1), (0, 3), and (4, negative 5). The interval [negative 2, 4] is marked on the horizontal axis. The interval [negative 5, 3] is marked on the vertical axis.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/22921/CNX_IntAlg_Figure_03_06_023_img_new.jpg?revision=1)

- Answer

-

The domain is \([−2,4]\). The range is \([−5,3]\).

Access this online resource for additional instruction and practice with graphs of functions.

Key Concepts

- Vertical Line Test

- A set of points in a rectangular coordinate system is the graph of a function if every vertical line intersects the graph in at most one point.

- If any vertical line intersects the graph in more than one point, the graph does not represent a function.

- Graph of a Function

- The graph of a function is the graph of all its ordered pairs, (x,y)(x,y) or using function notation, (x,f(x))(x,f(x)) where y=f(x).y=f(x).

fxf(x)name of functionx-coordinate of the ordered pairy-coordinate of the ordered pairfname of functionxx-coordinate of the ordered pairf(x)y-coordinate of the ordered pair

- The graph of a function is the graph of all its ordered pairs, (x,y)(x,y) or using function notation, (x,f(x))(x,f(x)) where y=f(x).y=f(x).

- Linear Function

- Constant Function

- Identity Function

- Square Function

- Cube Function

- Square Root Function

- Absolute Value Function