3.5: Dividing Polynomials

- Page ID

- 34893

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Use long division to divide polynomials.

- Use synthetic division to divide polynomials.

Using Long Division to Divide Polynomials

We are familiar with the long division algorithm for ordinary arithmetic. We begin by dividing into the digits of the dividend that have the greatest place value. We divide, multiply, subtract, include the digit in the next place value position, and repeat. For example, let’s divide 178 by 3 using long division.

Another way to look at the solution is as a sum of parts. This should look familiar, since it is the same method used to check division in elementary arithmetic.

\[\begin{align*} \text{dividend}&=(\text{divisor}{\cdot}\text{quotient})+\text{remainder} \\ 178&=(3{\cdot}59)+1 \\ &=177+1 \\ &=178\end{align*}\]

We call this the Division Algorithm and will discuss it more formally after looking at an example.

Division of polynomials that contain more than one term has similarities to long division of whole numbers. We can write a polynomial dividend as the product of the divisor and the quotient added to the remainder. The terms of the polynomial division correspond to the digits (and place values) of the whole number division. This method allows us to divide two polynomials. For example, if we were to divide \(2x^3−3x^2+4x+5\) by \(x+2\) using the long division algorithm, it would look like this:

\( \begin{array}{ll}

\qquad \quad {\color{red}{2x^2}} \; {\color{orange}{-7x}} \; {\color{Bittersweet}{+18}} & {\color{red}{\text{Step 1. Divide: }} \frac{2x^3}{x}} \qquad {\color{orange}{\text{Step 4. Divide: }} \frac{-7x^2}{x}=-7x}\qquad {\color{Bittersweet}{\text{Step 7. Divide: }} \frac{18x}{x}=18}\\

x+2 \; / \overline{ 2x^3-3x^2+4x+5} & \text{Original problem}\\

\qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{2x^3+4x^2}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 2. Multiply: }}} 2x^2(x+2) \\

\qquad \qquad \quad {\color{Cerulean}{-7x^2+4x}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 3. Subtract and Bring Down }}} \\

\qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{-7x^2-14x}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 5. Multiply: }}} -7x(x+2) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{18x+5}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 6. Subtract and Bring Down }}} \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \;\; {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{18x+36}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 8. Multiply: }}} 18(x+2) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{-31}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 9. Subtract. }}} \text{This is the remainder}\\

\end{array} \)

The result is: \( \qquad \dfrac{2x^3−3x^2+4x+5}{x+2}=2x^2−7x+18−\dfrac{31}{x+2} \)

or \(\qquad 2x^3−3x^2+4x+5=(x+2)(2x^2−7x+18)−31 \)

We can identify the dividend, the divisor, the quotient, and the remainder.

Writing the result in this manner illustrates the Division Algorithm.

The Division Algorithm

The Division Algorithm states that, given a polynomial dividend \(f(x)\) and a non-zero polynomial divisor \(d(x)\) where the degree of \(d(x)\) is less than or equal to the degree of \(f(x)\), there exist unique polynomials \(q(x)\) and \(r(x)\) such that

\[f(x)=d(x)q(x)+r(x) \nonumber\]

\(q(x)\) is the quotient and \(r(x)\) is the remainder. The remainder is either equal to zero or has degree strictly less than \(d(x)\).

If \(r(x)=0\), then \(d(x)\) divides evenly into \(f(x)\). This means that, in this case, both \(d(x)\) and \(q(x)\) are factors of \(f(x)\).

![]() How to: Given a polynomial and a binomial, use long division to divide the polynomial by the binomial

How to: Given a polynomial and a binomial, use long division to divide the polynomial by the binomial

- Set up the division problem.

- Determine the first term of the quotient by dividing the leading term of the dividend by the leading term of the divisor.

- Multiply the answer by the divisor and write it below the like terms of the dividend.

- Subtract the bottom binomial from the top binomial.

- Bring down the next term of the dividend.

- Repeat steps 2–5 until the degree of the remainder is less than the degree of the divisor.

- If the remainder is non-zero, express as a fraction using the divisor as the denominator.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Using Long Division to Divide a Second-Degree Polynomial

Divide \(5x^2+3x−2\) by \(x+1\).

Solution

\( \begin{array}{ll}

\qquad \quad {\color{red}{5x}} \; {\color{orange}{-2}} & {\color{red}{\text{Step 1. Divide: }} \frac{5x}{x}} \qquad {\color{orange}{\text{Step 4. Divide: }} \frac{-2}{x}=-7x} \\

x+1 \; / \overline{5x^2+3x-2} & \text{Original problem}\\

\qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{5x^2+5x}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 2. Multiply: }}} 5x(x+1) \\

\qquad \qquad \quad {\color{Cerulean}{-2x-2}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 3. Subtract and Bring Down }}} \\

\qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{-2x-2}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 5. Multiply: }}} -2(x+1) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{0}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 6. Subtract. }}} \text{There is no remainder} \\

\end{array} \)

The quotient is \(5x−2\). The remainder is 0. The result is \( \dfrac{5x^2+3x-2}{x+1} = 5x-2 \)

or \( \qquad 5x^2+3x−2=(x+1)(5x−2) \)

Analysis

This division problem had a remainder of 0. This tells us that the dividend is divided evenly by the divisor, and that the divisor is a factor of the dividend.

\(\PageIndex{2}\): Using Long Division to Divide a Third-Degree Polynomial

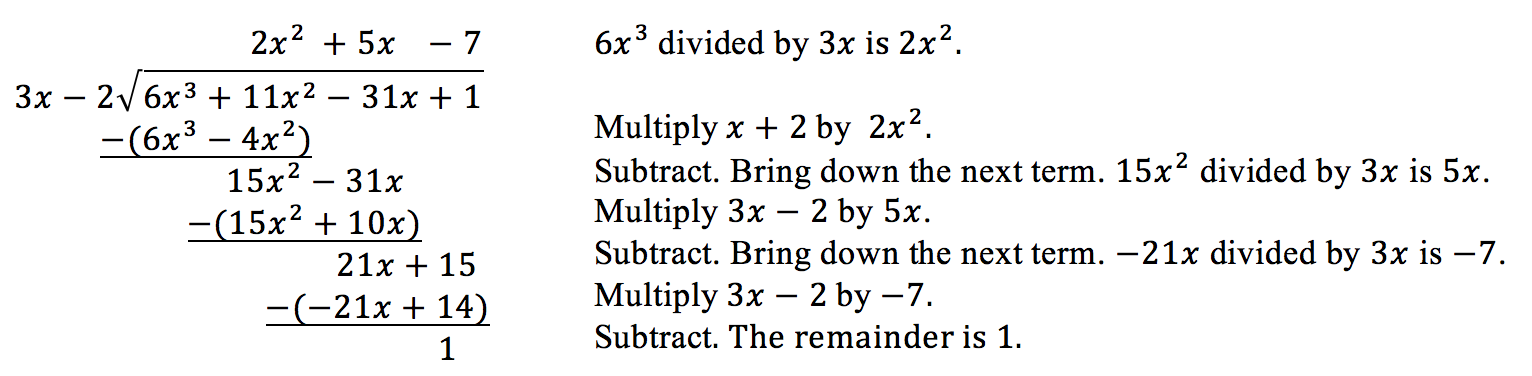

Divide \(6x^3+11x^2−31x+15\) by \(3x−2\).

Solution

There is a remainder of 1. We can express the result as: \( \dfrac{6x^3+11x^2−31x+15}{3x−2}=2x^2+5x−7+\dfrac{1}{3x−2} \)

Analysis

We can check our work by using the Division Algorithm to rewrite the solution. Then multiply.

\[(3x−2)(2x^2+5x−7)+1=6x^3+11x^2−31x+15\nonumber \]

Notice, as we write our result,

- the dividend is \(6x^3+11x^2−31x+15\)

- the divisor is \(3x−2\)

- the quotient is \(2x^2+5x−7\)

- the remainder is \(1\)

![]() Try It \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Try It \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Divide \(16x^3−12x^2+20x−3\) by \(4x+5\).

- Solution

-

\(4x^2−8x+15−\dfrac{78}{4x+5}\)

The divisor can also be a higher degree polynomial.

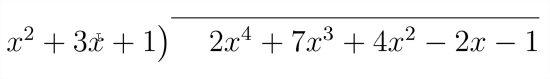

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Divide.

Solution

\( \begin{array}{ll}

\qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{red}{2x^2}} \; {\color{orange}{+x}} \; {\color{Bittersweet}{-1}} & {\color{red}{\text{Step 1. Divide: }} \frac{2x^4}{x^2}} \quad {\color{orange}{\text{Step 4. Divide: }} \frac{x^3}{x^2}}\quad {\color{Bittersweet}{\text{Step 7. Divide: }} \frac{-x^2}{x^2}}\\

x^2+3x+1 / \overline{ 2x^4+7x^3+4x^2-2x-1} & \text{Original problem}\\

\qquad \qquad \;\; {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{2x^4+6x^3+2x^2}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 2. Multiply: }}} 2x^2(x^2+3x+1) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \quad {\color{Cerulean}{x^3+2x^2-2x}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 3. Subtract and Bring Down }}} \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{x^3+3x^2+x}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 5. Multiply: }}} x(x^2+3x+1) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \quad {\color{Cerulean}{-x^2-3x-1}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 6. Subtract and Bring Down }}} \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{-x^2-3x-1}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 8. Multiply: }}} -1(x^2+3x+1) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad\; {\color{Cerulean}{0}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 9. Subtract. }}} \text{There is no remainder}\\

\end{array} \)

Because \(x^{2}+3 x+1\) divides evenly into \(2 x^{4}+7 x^{3}+4 x^{2}-2 x-1\) we have a zero remainder.

The final answer is \( \dfrac {2 x^{4}+7 x^{3}+4 x^{2}-2 x-1}{x^{2}+3 x+1} = 2x^2+x-1 \)

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Divide. \(\dfrac{3 x^{4}-8 x^{3}+19 x^{2}-15 x+10}{x^{2}-x+4}\)

Solution

\( \begin{array}{ll}

\qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{red}{3x^2}} \; {\color{orange}{-5x}} \; {\color{Bittersweet}{+2}} & {\color{red}{\text{Step 1. Divide: }} \frac{3x^4}{x^2}} \quad {\color{orange}{\text{Step 4. Divide: }} \frac{-5x^3}{x^2}}\quad {\color{Bittersweet}{\text{Step 7. Divide: }} \frac{2x^2}{x^2}}\\

x^2-x+4 / \overline{ 3x^4-8x^3+19x^2-15x+10} & \text{Original problem}\\

\qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{3x^4-3x^3+12x^2}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 2. Multiply: }}} x^2(x^2-x+4) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \quad {\color{Cerulean}{-5x^3+7x^2-15x}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 3. Subtract and Bring Down }}} \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{-5x^3+5x^2-20x}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 5. Multiply: }}} x(x^2-x+4) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \quad {\color{Cerulean}{2x^2+5x+10}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 6. Subtract and Bring Down }}} \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{ -( }} {\color{green}{ \underline{2x^2-2x+8}}} {\color{Cerulean}{ ) }} & {\color{green}{\text{Step 8. Multiply: }}} 2(x^2-x+4) \\

\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad {\color{Cerulean}{7x+2}}& {\color{Cerulean}{\text{Step 9. Subtract. }}} \text{This is the remainder}\\

\end{array} \)

Thus \(3 x^{4}-8 x^{3}+19 x^{2}-15 x+10 =\left(x^{2}-x+4\right) \left(3 x^{2}-5 x+2\right) +(7 x+2) \)

The final Answer is: \( \dfrac{3 x^{4}-8 x^{3}+19 x^{2}-15 x+10}{x^2-x+4} = 3x^2-5x+2 + \dfrac{7 x+2}{x^2-x+4} \)

Using Synthetic Division to Divide Polynomials

As we’ve seen, long division of polynomials can involve many steps and be quite cumbersome. Synthetic division is a shorthand method of dividing polynomials for the special case of dividing by a linear factor whose leading coefficient is 1.

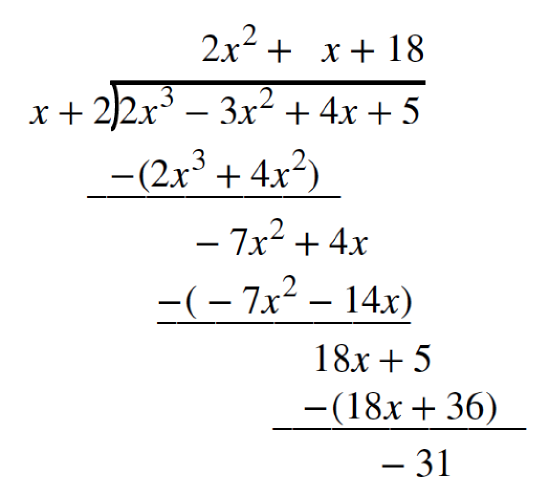

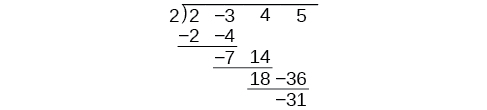

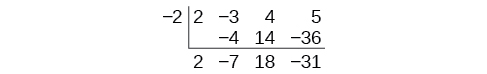

To illustrate the process, recall the example at the beginning of the section.

Divide \(2x^3−3x^2+4x+5\) by \(x+2\) using the long division algorithm.

The final form of the process looked like this:

There is a lot of repetition in the table. If we don’t write the variables but, instead, line up their coefficients in columns under the division sign and also eliminate the partial products, we already have a simpler version of the entire problem.

Synthetic division carries this simplification even a few more steps. Collapse the table by moving each of the rows up to fill any vacant spots. Also, instead of dividing by 2, as we would in division of whole numbers, then multiplying and subtracting the middle product, we change the sign of the “divisor” to –2, multiply and add. The process starts by bringing down the leading coefficient.

We then multiply it by the “divisor” and add, repeating this process column by column, until there are no entries left. The bottom row represents the coefficients of the quotient; the last entry of the bottom row is the remainder. In this case, the quotient is \(2x^2–7x+18\) and the remainder is –31.The process will be made more clear in the next example.

Synthetic Division

Synthetic division is a shortcut that can be used when the divisor is a binomial in the form \(x−k\). In synthetic division, only the coefficients are used in the division process.

![]() How to: Given two polynomials, use synthetic division to divide

How to: Given two polynomials, use synthetic division to divide

- Write \(k\) for the divisor.

- Write the coefficients of the dividend.

- Bring the lead coefficient down.

- Multiply the lead coefficient by \(k\). Write the product in the next column.

- Add the terms of the second column.

- Multiply the result by \(k\). Write the product in the next column.

- Repeat steps 5 and 6 for the remaining columns.

- Use the bottom numbers to write the quotient. The number in the last column is the remainder and has degree 0, the next number from the right has degree 1, the next number from the right has degree 2, and so on.

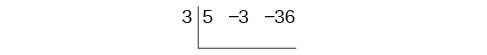

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Using Synthetic Division to Divide a Second-Degree Polynomial

Use synthetic division to divide \(5x^2−3x−36\) by \(x−3\).

Solution

Begin by setting up the synthetic division. Write \(k\) and the coefficients.

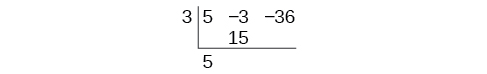

Bring down the lead coefficient. Multiply the lead coefficient by \(k\).

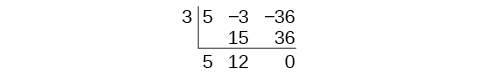

Continue by adding the numbers in the second column. Multiply the resulting number by \(k\). Write the result in the next column. Then add the numbers in the third column.

The result is \(5x+12\). The remainder is 0. So \(x−3\) is a factor of the original polynomial.

Analysis

Just as with long division, we can check our work by multiplying the quotient by the divisor and adding the remainder.

\[(x−3)(5x+12)+0=5x^2−3x−36\]

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\): Using Synthetic Division to Divide a Third-Degree Polynomial

Use synthetic division to divide \(4x^3+10x^2−6x−20\) by \(x+2\).

Solution

The binomial divisor is \(x+2\) so \(k=−2\). Add each column, multiply the result by –2, and repeat until the last column is reached.

\[ -2 \;\; \begin{array}{|rrrr} \;\; 4 & 10 & −6 & -20 \\ \text{} & -8 & -4 & 20 \\ \hline \end{array} \\ \begin{array}{rrrrrr} \qquad & 4\;\; & 2 & -10\;\;\; & \,0 & \nonumber \end{array} \]

The result is \(4x^2+2x−10\).

The remainder is 0. Thus, \(x+2\) is a factor of \(4x^3+10x^2−6x−20\).

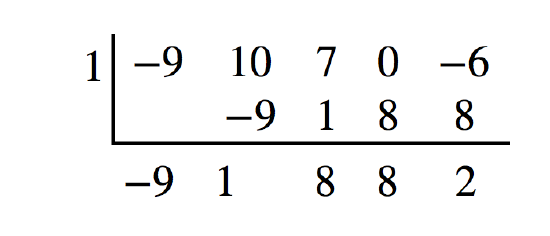

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\): Using Synthetic Division to Divide a Fourth-Degree Polynomial

Use synthetic division to divide \(−9x^4+10x^3+7x^2−6\) by \(x−1\).

Solution

Notice there is no x-term. We will use a zero as the coefficient for that term.

The result is \(−9x^3+x^2+8x+8+\dfrac{2}{x−1}\).

![]() \(\PageIndex{7}\)

\(\PageIndex{7}\)

Use synthetic division to divide \(3x^4+18x^3−3x+40\) by \(x+7\).

- Solution

-

\(3x^3−3x^2+21x−150+\frac{1,090}{x+7}\)

Key Equations

Division Algorithm \(f(x)=d(x)q(x)+r(x)\) where \(q(x){\neq}0\)

Key Concepts

- Polynomial long division can be used to divide a polynomial by any polynomial with equal or lower degree.

- The Division Algorithm tells us that a polynomial dividend can be written as the product of the divisor and the quotient added to the remainder.

- Synthetic division is a shortcut that can be used to divide a polynomial by a binomial in the form x−k.

- Polynomial division can be used to solve application problems, including area and volume.

Glossary

Division Algorithm

given a polynomial dividend \(f(x)\) and a non-zero polynomial divisor \(d(x)\) where the degree of \(d(x)\) is less than or equal to the degree of \(f(x)\), there exist unique polynomials \(q(x)\) and \(r(x)\) such that \(f(x)=d(x)q(x)+r(x)\) where \(q(x)\) is the quotient and \(r(x)\) is the remainder. The remainder is either equal to zero or has degree strictly less than \(d(x)\).

synthetic division

a shortcut method that can be used to divide a polynomial by a binomial of the form \(x−k\)

Contributors

Jay Abramson (Arizona State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at https://openstax.org/details/books/precalculus.