5.2: Right Triangle Trigonometry

- Page ID

- 34917

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Trigonometric Functions: Ratios of Sides of a Right Triangle

In this section we introduce right triangle trigonometry and explore right triangle applications of trigonometric functions. In later sections we will examine trigonometric functions as ratios of the sides of a triangle drawn inside a circle, and discuss the role of those functions in finding points on the circle.

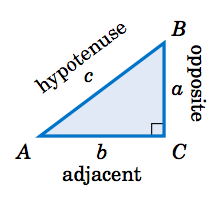

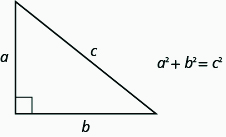

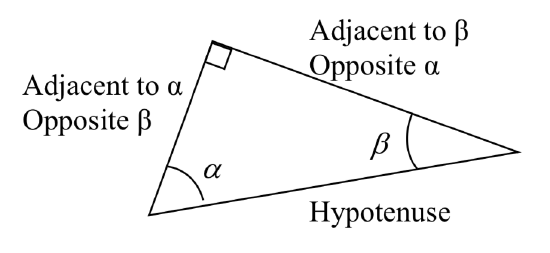

Trigonometric functions are ratios of two of the three sides of a right triangle. The longest side of the right triangle is the hypotenuse. The other two sides are defined in terms of their relationship to one of the acute angles in the right triangle -- the side opposite the chosen angle, and the side adjacent (next to) that angle.

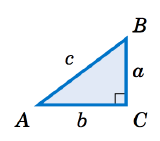

Angles in a right triangle are frequently designated with upper case letters like \(A,\) \(B,\) and \(C\) and the sides opposite each of these angles are labeled with the corresponding lower case letter. \(C\) is often the \(90^{\circ}\) angle, so side \(c\) would be the hypotenuse. Thus the side opposite angle \(A\) is side \(a\), and the side adjacent to angle \(A\) is side \(b\). These relationships and the naming convention is illustrated in the diagram on the right.

Angles in a right triangle are frequently designated with upper case letters like \(A,\) \(B,\) and \(C\) and the sides opposite each of these angles are labeled with the corresponding lower case letter. \(C\) is often the \(90^{\circ}\) angle, so side \(c\) would be the hypotenuse. Thus the side opposite angle \(A\) is side \(a\), and the side adjacent to angle \(A\) is side \(b\). These relationships and the naming convention is illustrated in the diagram on the right.

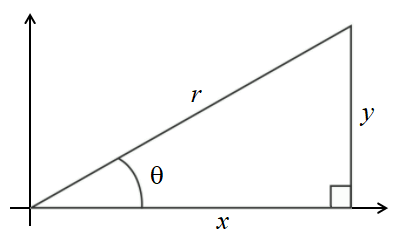

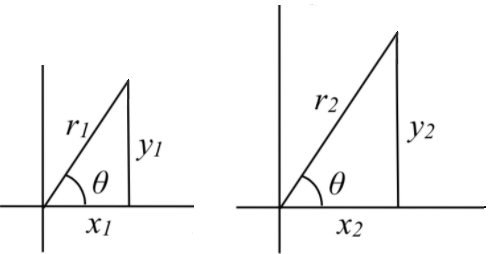

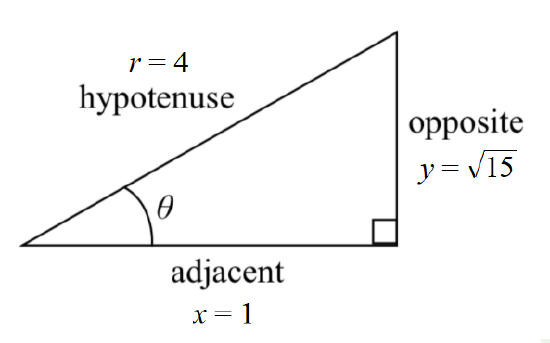

The triangle can be oriented any where in space, but when the triangle is placed in standard position with the chosen acute angle \( \theta\) at the origin, these sides can be expressed equivalently in terms of \(y\) for the opposite side, \(x\) for the adjacent side, and \(r\) for the hypotenuse. The point \( (x, y) \) is a point on the terminal side of the angle.

RIGHT TRIANGLE RELATIONSHIPS

Given a right triangle with an angle of \(\theta\)

\( \begin{array}{rllrll}

\sin \theta &= \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}} &= \dfrac{y}{r} \qquad &\csc \theta &= \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{opposite}} &= \dfrac{r}{y} \\

\cos \theta &= \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}} &= \dfrac{x}{r} \qquad &\sec \theta &= \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{adjacent}} &= \dfrac{r}{x} \\

\tan \theta &= \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}} &= \dfrac{y}{x} \qquad &\cot \theta &= \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{opposite}} &= \dfrac{x}{y} \\

\end{array} \)

A common mnemonic for remembering these relationships is SohCahToa, formed from the first letters of “Sine is opposite over hypotenuse, Cosine is adjacent over hypotenuse, Tangent is opposite over adjacent.”

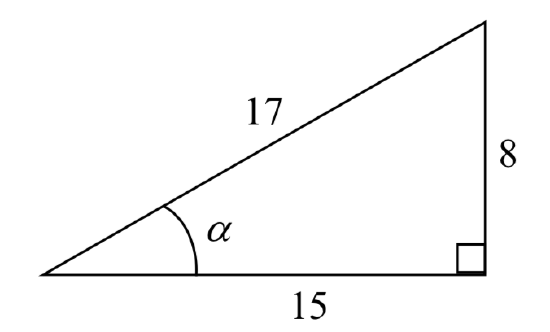

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Find trigonometric ratios given 3 sides of a right triangle

Given the triangle shown, find the value for \(\text{cos}(\alpha)\).

The side adjacent to the angle is 15, and the hypotenuse of the triangle is 17, so

\[\text{cos}(\alpha) = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}} = \dfrac{15}{17}\nonumber\]

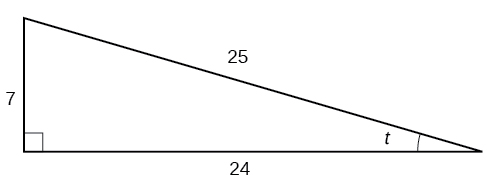

![]() Try It \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Try It \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Given the triangle shown, find the value of \(\sin t\).

Given the triangle shown, find the value of \(\sin t\).

- Answer

- \(\sin t = \dfrac{7}{25}\)

Given Two Sides, Find the 3rd Side and All Trigonometric Ratios

It is not necessary that the lengths of all three sides of the right triangle be known initially. The Theorem of Pythagoras can be used to find the third side if we are given the lengths of only two sides of a right triangle.

In any right triangle, where \(a\) and \(b\) are the lengths of the legs, and \(c\) is the length of the hypotenuse, the sum of the squares of the lengths of the two legs equals the square of the length of the hypotenuse.

We will use the Pythagorean Theorem in the next example.

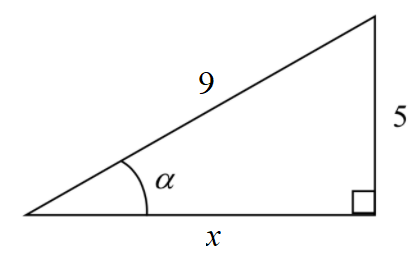

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Find trigonometric ratios given 2 sides of a right triangle

Given a triangle with a hypotenuse of \(9\) and side opposite to angle \( \alpha\) of \(5\), find the sine, cosine and tangent for angle \( \alpha\).

Solution.

Solution.

The triangle with the given information is illustrated on the right. The third side, which in this case is the "adjacent" side, can be found by using the Theorem of Pythagoras \( a^2 + b^2 = c^2\). Always remember that in the formula, \(c\) is the length of the hypotenuse. From \( x^2 + 5^2 = 9^2\) we obtain \(x^2 = 81-25 = 56\). So \(x = \sqrt{56} = 2\sqrt{14}\).

Now that all three sides have been found, values for the trigonometric functions can be calculated. Always remember to rationalize denominators!

\( \sin \alpha = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}} = \dfrac{5}{9} \) \( \qquad\) \( \cos \alpha = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}} =\dfrac{2\sqrt{14}}{9}\) \( \qquad\) \( \tan \alpha = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}} = \dfrac{5}{2\sqrt{14}} = \dfrac{5\sqrt{14}}{28} \)

![]() Try It \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Try It \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Given a triangle with the side adjacent to angle \(\theta\) being \(x=2\) and the side opposite angle \(\theta\) being \(x=5\), find the secant, cosecant, and cotangent for angle \(\theta\).

- Answer

-

From \(x^2 + y^2 = r^2\) we obtain \( r = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}\) and so \(r = \sqrt{29}\).

Therefore, \( \csc \theta = \dfrac{\sqrt{29}}{5} , \; \sec \theta = \dfrac{\sqrt{29}}{2}, \; \cot \theta = \dfrac{5}{2}, \)

Given One Trigonometric Ratio, find all others

One important point to make here is that it is only the angle that determines the values of these trigonometric ratios, not the size of the triangle being used. This is because triangles constructed with the same angles but different length sides are similar triangles, so their ratios will be the same.

Thus, \( \dfrac{y_{1} }{r_{1} } =\dfrac{y_{2} }{r_{2} } \qquad \dfrac{x_{1} }{r_{1} } =\dfrac{x_{2} }{r_{2} }\)

A trigonometric ratio is the ratio of two sides of a right triangle. Since right triangles that are similar can be used to establish values for trigonometric functions, the numerator of the trigonometric ratio can serve as the length of one of the sides; the denominator can serve as the length of another side. Whether these sides are the hypotenuse of the triangle or the side opposite or adjacent to the given angle depends on which trigonometric ratio is being used.

![]() How to: Find three sides of a right triangle, given one trigonometric ratio.

How to: Find three sides of a right triangle, given one trigonometric ratio.

Given a trigonometric ratio, \( \sin A = \frac{a}{c} \) or \( \cos A = \frac{b}{c} \) or \( \tan A = \frac{a}{b} \)

Given a trigonometric ratio, \( \sin A = \frac{a}{c} \) or \( \cos A = \frac{b}{c} \) or \( \tan A = \frac{a}{b} \)

- Draw a right triangle with angle \(A\) and the two known sides labeled according to the diagram on the right. If the trigonometric ratio has no denominator, use \(1\) for the value of the denominator.

- Use the Pythagorean Theorem \( a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \) to find the value of the missing 3rd side of the right triangle.

- Use the definitions to find the values of the other trigonometric ratios.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Find all trigonometric ratios given one ratio

Given \( \sec \theta = 4 \), find the other five trigonometric ratios for angle \( \theta \).

Solution

G iven \( \sec \theta = 4 \), we can construct the ratio \( \sec \theta = \dfrac{4}{1} = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{adjacent}} = \dfrac{r}{x} \).

iven \( \sec \theta = 4 \), we can construct the ratio \( \sec \theta = \dfrac{4}{1} = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{adjacent}} = \dfrac{r}{x} \).

Draw a triangle to help visualize the relationships represented by this trigonometric ratio.

Using the Theorem of Pythagoras \( x^2 +y^2 = r^2\) and knowing \(r = 4\), \(x = 1\), we obtain \( 1^2 + y^2 = 4^2\). Thus, \( y^2 = 16 - 1 = 15 \) and so \( y = \sqrt{15} \).

Now that all three sides of the right triangle are known, the definitions can be used to find the other five trigonometric ratios.

\( \sin \theta = \dfrac{y}{r} = \dfrac{\sqrt{15}}{4} \) \( \cos \theta = \dfrac{x}{r} = \dfrac{1}{4} \) \( \tan \theta = \dfrac{y}{x} = \sqrt{15} \)

\( \csc \theta = \dfrac{r}{y} = \dfrac{4}{\sqrt{15}} = \dfrac{4 \sqrt{15}}{15} \) \( \cot \theta = \dfrac{x}{y} = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{15}} = \dfrac{\sqrt{15}}{15} \)

![]() Try It \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Try It \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Given \( \tan \theta = \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \), find the other five trigonometric ratios for angle \( \theta \).

- Answer

-

\( \sin \theta = \dfrac{\sqrt{21}}{7} , \; \cos \theta = \dfrac{2\sqrt{7}}{7}, \; \csc \theta = \dfrac{\sqrt{21}}{3}, \; \sec \theta = \dfrac{\sqrt{7}}{2}, \; \cot \theta = \dfrac{2\sqrt{3}}{3} \)

Given One Side and an Angle, Find all Other Sides and Angles

In previous examples, we evaluated the sine and cosine in triangles where we knew all three sides. But the real power of right-triangle trigonometry emerges when we look at triangles in which we know an angle but do not know all the sides.

![]() How to: Given the side and one acute angle of a right triangle, find the remaining sides.

How to: Given the side and one acute angle of a right triangle, find the remaining sides.

- For each side, select the trigonometric function with the unknown side as either the numerator or the denominator and the known side as the corresponding denominator or the numerator.

- Write an equation setting the function value of the known angle equal to the ratio of the corresponding sides.

- Using the value of the trigonometric function and the known side length, solve for the missing side length.

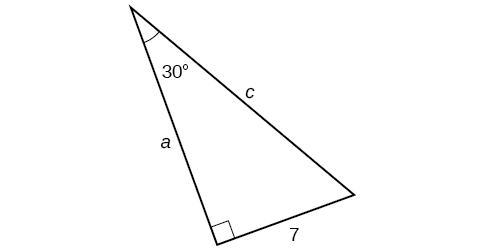

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Finding Missing Side Lengths Using Trigonometric Ratios

Find the unknown sides of the triangle below.

Solution

We are given the angle \(30^{\circ}\) and the opposite side (OPP).

To find the adjacent side (ADJ) choose the ratio that uses both OPP (given) and ADJ (unknown): \( \tan A = \frac{OPP}{ADJ}.\)

Write the equation with the given and unknown values: \( \qquad \tan (30°)= \dfrac{7}{a} \)

Rearrange to solve for \(a\). \( \qquad a =\dfrac{7}{ \tan (30°)} =12.1 \)

To find the hypotenuse (HYP), choose the ratio that uses both OPP (given) and HYP (unknown): \( \sin A = \frac{OPP}{HYP}.\)

Substitute: \( \qquad \sin (30°)= \dfrac{7}{c} \)

Rearrange to solve for \(c\). \( \qquad c = \dfrac{7}{\sin (30°)} =14 \)

Notice that if we know at least one of the non-right angles of a right triangle and one side, we can find the rest of the sides and angles.

![]() Try It \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Try It \(\PageIndex{4}\)

A right triangle has one angle of \(\dfrac{\pi }{3}\) (radians) and a hypotenuse of 20. Find the unknown sides and angles of the triangle.

- Answer

-

\[\text{cos} \left(\dfrac{\pi}{3} \right) = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypoteuse}} = \dfrac{\text{Adj}}{20} \quad \rightarrow \quad

\text{adjacent} = 20 \text{cos} \left(\dfrac{\pi}{3} \right) = 20 \left(\dfrac{1}{2} \right) = 10\nonumber\]\[\text{sin} \left(\dfrac{\pi}{3} \right) = \dfrac{\text{Opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}} = \dfrac{\text{Opp}}{20} \quad \rightarrow \quad

\text{opposite} = 20 \text{sin} \left(\dfrac{\pi}{3} \right) = 20 \left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \right) = 10\sqrt{3}\nonumber\]Missing angle = \( \frac{\pi}{2} - \frac{\pi}{3} = \frac{\pi}{6}\).

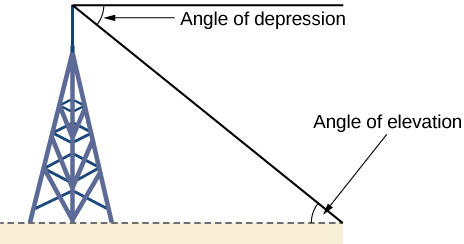

Right Triangle Trigonometry Used to Solve Applied Problems

Right-triangle trigonometry has many practical applications. For example, the ability to compute the lengths of sides of a triangle makes it possible to find the height of a tall object without climbing to the top or having to extend a tape measure along its height. We do so by measuring a distance from the base of the object to a point on the ground some distance away, where we can look up to the top of the tall object at an angle. The angle of elevation of an object above an observer is the angle between the horizontal and the line from the observer's eye to the object. The right triangle created in this way has sides that represent the unknown height, the measured distance from the base, and the angled line of sight from the ground to the top of the object. Knowing the measured distance to the base of the object and the angle of the line of sight, we can use trigonometric functions to calculate the unknown height. Similarly, we can form a triangle from the top of a tall object by looking downward. The angle of depression of an object below an observer is the angle between the horizontal and the line from the observer's eye to the object.

Right-triangle trigonometry has many practical applications. For example, the ability to compute the lengths of sides of a triangle makes it possible to find the height of a tall object without climbing to the top or having to extend a tape measure along its height. We do so by measuring a distance from the base of the object to a point on the ground some distance away, where we can look up to the top of the tall object at an angle. The angle of elevation of an object above an observer is the angle between the horizontal and the line from the observer's eye to the object. The right triangle created in this way has sides that represent the unknown height, the measured distance from the base, and the angled line of sight from the ground to the top of the object. Knowing the measured distance to the base of the object and the angle of the line of sight, we can use trigonometric functions to calculate the unknown height. Similarly, we can form a triangle from the top of a tall object by looking downward. The angle of depression of an object below an observer is the angle between the horizontal and the line from the observer's eye to the object.

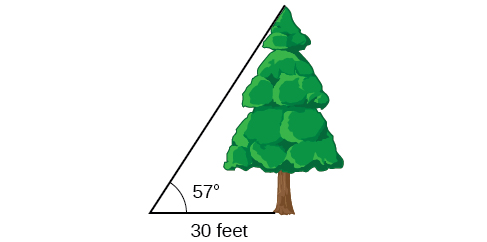

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

To find the height of a tree, a person walks to a point 30 feet from the base of the tree, and measures the angle from the ground to the top of the tree to be 57 degrees. Find the height of the tree.

Solution

We can introduce a variable, \(h\), to represent the height of the tree. The two sides of the triangle that are most important to us are the side opposite the angle, the height of the tree we are looking for, and the adjacent side, which is 30 feet long.

We can introduce a variable, \(h\), to represent the height of the tree. The two sides of the triangle that are most important to us are the side opposite the angle, the height of the tree we are looking for, and the adjacent side, which is 30 feet long.

The trigonometric function which relates the side opposite of the angle and the side adjacent to the angle is the tangent.

\(\text{tan} (57^{\circ}) = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}} = \dfrac{h}{30}\)

Solving for \(h\), \(h=30\tan (57{}^\circ )\)

Using a calculator, we can approximate a value for the height, \(h=30\tan (57{}^\circ )\approx 46.2\text{ feet}\)

The tree is approximately 46 feet tall.

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\)

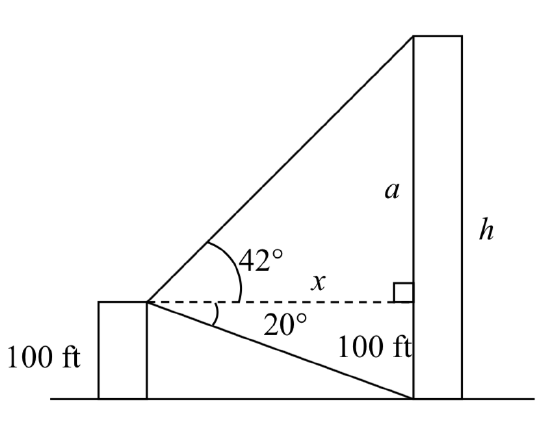

A person standing on the roof of a 100 foot tall building is looking towards a skyscraper a few blocks away, wondering how tall it is. The angle of declination from the roof of the building to the base of the skyscraper is observed to be 20 degrees and the angle of inclination to the top of the skyscraper is 42 degrees.

Solution

To approach this problem, it would be good to start with a picture. Although we are interested in the height,  \(h\), of the skyscraper, it can be helpful to also label other unknown quantities in the picture – in this case the horizontal distance \(x\) between the buildings and \(a\), the height of the skyscraper above the person.

\(h\), of the skyscraper, it can be helpful to also label other unknown quantities in the picture – in this case the horizontal distance \(x\) between the buildings and \(a\), the height of the skyscraper above the person.

To start solving this problem, notice we have two right triangles. In the top triangle, we know one angle is 42 degrees, but we don’t know any of the sides of the triangle, so we don’t yet know enough to work with this triangle.

In the lower right triangle, we know one angle is 20 degrees, and we know the vertical height measurement of 100 ft. Since we know these two pieces of information, we can solve for the unknown distance \(x\).

\(\text{tan} (20^{\circ}) = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}} = \dfrac{100}{x}\)

Solving for \(x\)

\(x \text{ tan} (20^{\circ}) = 100\)

\(x = \dfrac{100}{\text{tan} (20^{\circ})}\)

Now that we have found the distance \(x\), we know enough information to solve the top right triangle.

\(\text{tan} (42^{\circ}) = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}} = \dfrac{a}{x} = \dfrac{a}{100/\text{tan}(20^{\circ})}\)

\(\text{tan} (42^{\circ}) = \dfrac{a\text{ tan} (20^{\circ})}{100} \quad \rightarrow \quad 100 \text{ tan} (42^{\circ}) = a\text{ tan} (20^{\circ}) \quad \rightarrow \quad \dfrac{100 \text{ tan} (42^{\circ})}{\text{ tan} (20^{\circ})} = a\)

Approximating, \(a=\dfrac{100\tan (42{}^\circ )}{\tan (20{}^\circ )} \approx 247.4\text{ feet}\)

Adding the height of the first building, we determine that the skyscraper is about 347 feet tall.

Find an angle given two sides of a right triangle.

Sometimes an angle that has a particular trigonometric ratio is desired. In this situation we use the inverse trigonometric functions \( \sin^{-1},\) \( \cos^{-1},\) and \( \tan^{-1}\) on a calculator to find an angle with a given trigonometric ratio.

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\)

Use a calculator to find the angle in degrees to the nearest tenth with the following trigonometric ratios.

a. \( \sin A = .3877\) b. \( \cos A = .6691\) \( \tan A = 4.6543\)

Solution

Use the inverse trigonometric function keys on a calculator. Be sure you are in degree mode in order to get an angle measurement in degrees!

a. \( A = \sin^{-1} (.3877) \approx 22.8^{\circ} \) b. \( A = \cos^{-1} (.6691) \approx 48.0^{\circ} \) c. \( A = \tan^{-1} (4.6543) \approx 77.9^{\circ} \)

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\)

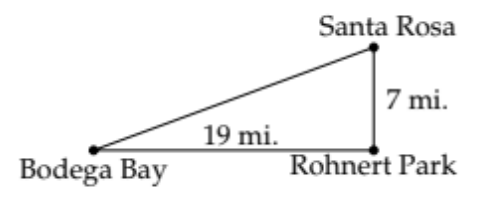

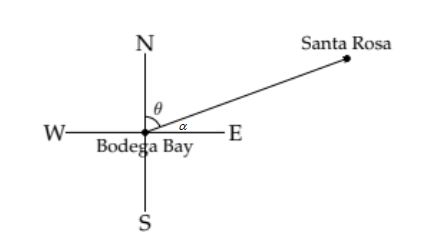

Santa Rosa, California is 7 miles due north of Rohnert Park. Bodega Bay is 19 miles due west of Rohnert Park (as the crow flies). What is the bearing of Santa Rosa from Bodega Bay?

Santa Rosa, California is 7 miles due north of Rohnert Park. Bodega Bay is 19 miles due west of Rohnert Park (as the crow flies). What is the bearing of Santa Rosa from Bodega Bay?

Solution

To answer the question we'll need another diagram:

If we knew the angle \(\theta\), then we could conclude that the bearing of Santa Rosa from Bodega Bay is \(\theta\) degrees East of North. From the previous diagram we can see that we can't find \(\theta\) directly, but we can find \( \alpha,\) the complement of \(\theta\)

\( \tan \alpha=\frac{7}{19} \) so \(\alpha = \tan^{-1} \frac{7}{19} \approx 20.2^{\circ}\)

\[ \text { Therefore, } \theta \approx 90^{\circ}-20.2^{\circ} \approx 69.8^{\circ} \nonumber \]

Thus the bearing of Santa Rosa from Bodega Bay is \(N 69.8^{\circ} E\), or \(69.8^{\circ}\) East of North.

Cofunction Identities

When working with general right triangles, the same rules apply regardless of the orientation of the triangle. In fact, we can evaluate the sine and cosine of either of the two acute angles in the triangle.

Example \(\PageIndex{9}\)

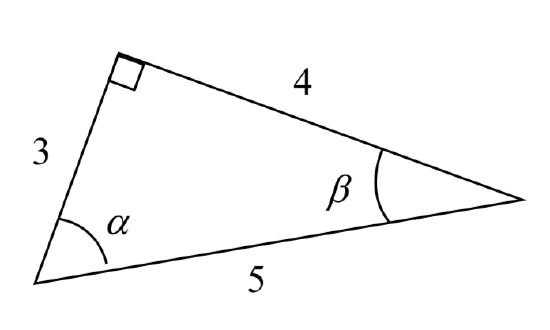

Using the triangle shown, evaluate \( \sin α, \cos α, \tan α, \sec α, \csc α,\) and \( \cot α\). Also evaluate sin(\(\beta\)) and cos(\(\beta\)).

Solution

\( \sin α = \dfrac{\text{opposite } α}{\text{hypotenuse}} = \dfrac{4}{5}

\; \qquad \cos α = \dfrac{\text{adjacent to }α}{\text{hypotenuse}}=\dfrac{3}{5}

\; \qquad \tan α = \dfrac{\text{opposite }α}{\text{adjacent to }α}=\dfrac{4}{3} \)

\( \csc α = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{opposite }α}=\dfrac{5}{4} \qquad \sec α = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{adjacent to }α}= \dfrac{5}{3} \qquad \cot α = \dfrac{\text{adjacent to }α}{\text{opposite }α}=\dfrac{3}{4} \)

\(\text{sin}(\beta) = \dfrac{\text{opposite } \beta}{\text{hypotenuse}} = \dfrac{3}{5}\) \( \;\; \text{cos}(\beta) = \dfrac{\text{adjacent to } \beta}{\text{hypotenuse}} = \dfrac{4}{5} \)

![]() Try It \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Try It \(\PageIndex{9}\)

A right triangle is drawn with angle \(\alpha\) opposite a side with length 33, angle \(\beta\) opposite a side with length 56, and hypotenuse 65. Evaluate \( \sin α, \cos α,\tan α, \sec α, \csc α,\) and \(\cot α\). Also, find the sine and cosine of \(\beta\)

- Answer

-

\( \sin α = \frac{33}{65}, \; \cos α= \frac{56}{65}, \; \tan α= \frac{33}{56}, \; \sec α = \frac{65}{56}, \; \csc α= \frac{65}{33}, \; \cot α= \frac{56}{33} \) \( \qquad \) \(\text{sin} (\beta) = \frac{56}{65}, \; \text{cos} (\beta) = \frac{33}{65}\)

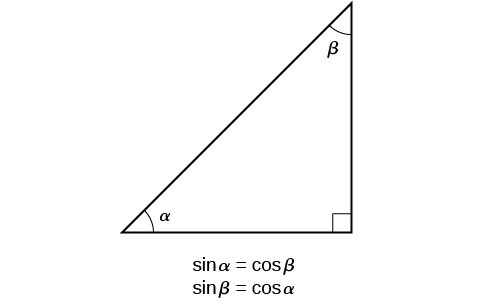

You may have noticed in the examples above that \(\cos (\alpha )=\sin (\beta )\) and \(\cos (\beta )=\sin (\alpha )\).

This makes sense since the side opposite \(\alpha\) is the same side that is adjacent to \(\beta\). Since the three angles in a right triangle need to add up to \(180^{\circ}\) (or \(\pi\) if angles are measured in radians), then the two acute angles in a right triangle must add to \(90^{\circ}\) (or \(\dfrac{\pi }{2}\) (radians). Therefore, \(\beta =90^{\circ} -\alpha\), and \(\alpha =90^{\circ} -\beta\). Since \(\cos (\alpha )=\sin (\beta )\), then \(\cos (\alpha )=\sin \left(90^{\circ} -\alpha \right)\).

So we may state a cofunction identity: If any two angles are complementary, the sine of one is the cosine of the other, and vice versa. This identity is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Using this identity, we can state without calculating, for instance, that \(\sin (15^{\circ}) = \cos (90^{\circ}- 15^{\circ}) = \cos (75^{\circ}) \), and that \(\sin (75^{\circ}) = \cos (90^{\circ}- 75^{\circ}) = \cos (15^{\circ}) \).

In a similar manner it can be shown that \(\sec (\alpha )=\csc (\beta )\) and \(\sec (\beta )=\csc (\alpha )\). It can also be shown that \(\cot (\alpha )=\tan (\beta )\) and \(\cot (\beta )=\tan (\alpha )\). These relationships are summarized below.

COFUNCTION IDENTITIES

Cofunctions of complementary angles are equal.

The angles \(d^{\circ}\) and \((90 ^{\circ}-d^{\circ})\) are complementary angles. Angles \(r\) and \(\left( \dfrac{π}{2} - r \right)\) are complementary angles.

Sine and cosine are cofunctions. Secant and cosecant are cofunctions. Tangent and cotangent are cofunctions.

The cofunction identities for an angle \(t\) in degrees are listed below. (If \(t\) is in radians, then use \( \dfrac{π}{2} \) in place of \(90^{\circ}).\)

| \( \sin t= \cos (90^{\circ}−t)\) | \( \sec t= \csc (90^{\circ}−t) \) | \( \tan t= \cot (90^{\circ}−t) \) |

| \( \cos t= \sin (90^{\circ}−t)\) | \( \csc t= \sec (90^{\circ}−t)\) | \( \cot t= \tan (90^{\circ}−t)\) |

![]() How to: Given the sine and cosine of an angle, find the sine or cosine of its complement.

How to: Given the sine and cosine of an angle, find the sine or cosine of its complement.

- To find the sine of the complementary angle, find the cosine of the original angle.

- To find the cosine of the complementary angle, find the sine of the original angle.

Example \(\PageIndex{10}\): Using Cofunction Identities

If \( \sin t = \dfrac{5}{12},\) find \( \cos (90^{\circ}−t)\).

Solution

According to the cofunction identities for sine and cosine, \( \sin t= \cos (90^{\circ}−t). \) So \( \cos (90^{\circ}−t)= \dfrac{5}{12}. \)

![]() Try It \(\PageIndex{10}\)

Try It \(\PageIndex{10}\)

If \(\csc (30^{\circ})=2,\) find \( \sec (60^{\circ}).\)

- Answer

-

\(2\)

Key Concepts

- We can define trigonometric functions as ratios of the side lengths of a right triangle.

- The same side lengths can be used to evaluate the trigonometric functions of either acute angle in a right triangle.

- Any two complementary angles could be the two acute angles of a right triangle.

- If two angles are complementary, the cofunction identities state that the sine of one equals the cosine of the other and vice versa.

- We can use trigonometric functions of an angle to find unknown side lengths. Select the trigonometric function representing the ratio of the unknown side to the known side.

- Right-triangle trigonometry permits the measurement of inaccessible heights and distances. The unknown height or distance can be found by creating a right triangle in which the unknown height or distance is one of the sides, and another side and angle are known.

Glossary

- adjacent side

- in a right triangle, the side between a given angle and the right angle

- angle of depression

- the angle between the horizontal and the line made by an observer’s eye looking at an object positioned lower than the observer

- angle of elevation

- the angle between the horizontal and the line made by an observer’s eye looking at an object positioned higher than the observer

- opposite side

- in a right triangle, the side most distant from a given angle

- hypotenuse

- the side of a right triangle opposite the right angle