0.2: Relations

- Page ID

- 131014

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Definition: Binary Relation

Let \(S\) be a nonempty set. Then any subset \(R\) of \(S \times S\) is said to be a relation over \(S\). In other words, a relation is a rule that is defined between two elements in \(S\). Intuitively, if \(R\) is a relation over \(S\), then the statement \(a R b\) is either true or false for all \(a,b\in S\).

If the statement \(a R b\) is false, we denote this by \( a \not R b\).

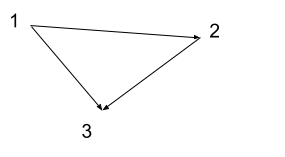

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Let \(S=\{1,2,3\}\). Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a < b\), for \(a, b \in S\).

Then \(1 R 2, 1 R 3, 2 R 3 \) and \( 2 \not R 1\).

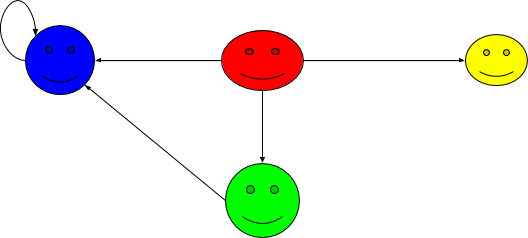

We can visualize the above binary relation as a graph, where the vertices are the elements of S, and there is an edge from \(a\) to \(b\) if and only if \(a R b\), for \(a b\in S\).

The following are some examples of relations defined on \(\mathbb{Z}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\):

- Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a < b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\).

- Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a >b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\).

- Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a \leq b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\).

- Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a \geq b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\).

- Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a = b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Definition: Divisor/Divides

Let \( a\) and \(b\) be integers. We say that \(a\) divides \(b\) is denoted \(a\mid b\), provided we have an integer \(m\) such that \(b=am\). In this case we can also say the following:

- \(b\) is divisible by \(a\)

- \(a\) is a factor of \(b\)

- \(a\) is a divisor of \(b\)

- \(b\) is a multiple of \(a\)

If \(a\) does not divide \(b\), then it is is denoted by \(a \not \mid b\).

Properties of binary relation:

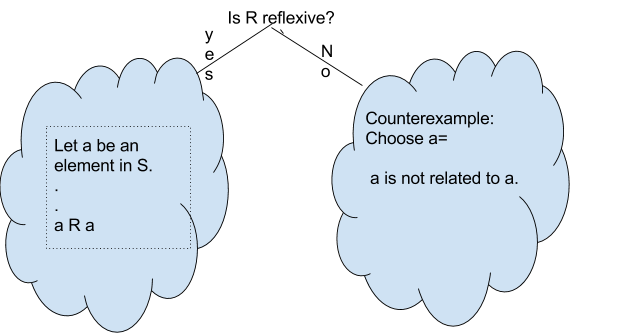

Definition: Reflexive

Let \(S\) be a set and \(R\) be a binary relation on \(S\). Then \(R\) is said to be reflexive if \( a R a, \forall a \in S.\)

We will follow the template below to answer the question about reflexive.

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\):

Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a < b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\). Is \(R\) reflexive?

Counter Example:

Choose \(a=2.\)

Since \( 2 \not< 2\), \(R\) is not reflexive.

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\):

Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a \mid b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\). Is \(R\) reflexive?

Proof:

Let \( a \in \mathbb{Z}\). Since \(a=(1) (a)\), \(a \mid a\).

Thus \(R\) is reflexive. \( \Box\)

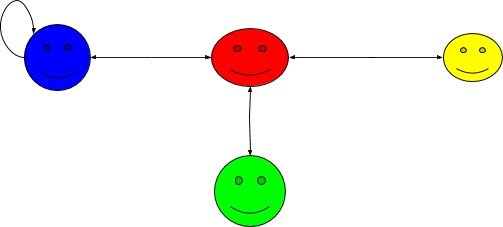

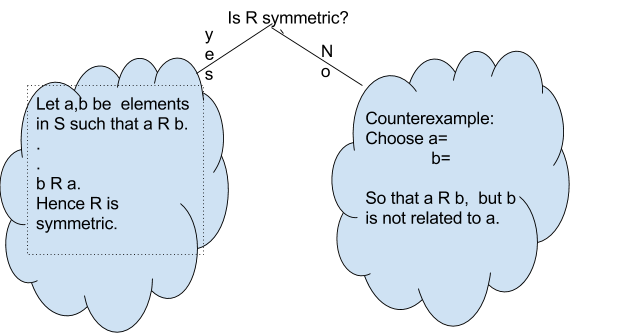

Definition: Symmetric

Let \(S\) be a set and \(R\) be a binary relation on \(S\). Then \(R\) is said to be symmetric if the following statement is true:

\( \forall a,b \in S\), if \( a R b \) then \(b R a\), in other words, \( \forall a,b \in S, a R b \implies b R a.\)

Example \(\PageIndex{8}\): Visually

\(\forall a,b \in S, a R b \implies b R a.\) holds!

We will follow the template below to answer the question about symmetric.

Example \(\PageIndex{9}\):

Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a < b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\). Is \(R\) symmetric?

Counter Example:

\(1<2\) but \(2 \not < 1\).

Example \(\PageIndex{10}\):

Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a \mid b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\). Is \(R\) symmetric?

Counter Example:

\(2 \mid 4\) but \(4 \not \mid 2\).

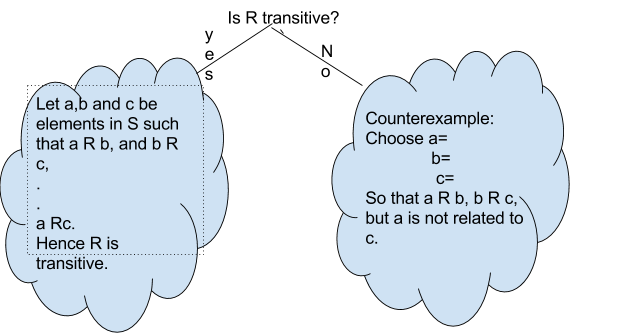

Definition: Transitive

Let \(S\) be a set and \(R\) be a binary relation on \(S\). Then \(R\) is said to be transitive if the following statement is true

\( \forall a,b,c \in S,\) if \( a R b \) and \(b R c\), then \(a R c\).

In other words, \( \forall a,b,c \in S\), \( a R b \wedge b R c \implies a R c\).

Example \(\PageIndex{14}\): VISUALLY

\( \forall a,b,c \in S\), \( a R b \wedge b R c \implies a R c\) holds!

We will follow the template below to answer the question about transitive.

Example \(\PageIndex{15}\):

Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a < b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\). Is \(R\) transitive?

Example \(\PageIndex{16}\):

Define \(R\) by \(a R b\) if and only if \(a \mid b\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z_+}\). Is \(R\) transitive?

Definition: Equivalence Relation

A binary relation is an equivalence relation on a nonempty set \(S\) if and only if the relation is reflexive(R), symmetric(S) and transitive(T).

Definition: Equivalence Relation

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): \(=\)

Let \(S=\mathbb{R}\) and \(R\) be =. Is the relation a) reflexive, b) symmetric, c) antisymmetric, d) transitive, e) an equivalence relation, f) a partial order.

Solution:

-

Yes \(R \) is reflexive.

Proof:

Let \(a \in \mathbb{R} \).

Then \(a=a \).

Hence \(R \) is reflexive. \(\blacksquare \)

Yes \(R \) is symmetric.

Proof:

Let \((a,b) \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(a=b.\)

Clearly \(b=a \).

Hence \(R \) is symmetric. \(\blacksquare \)

Yes \(R \) is antisymmetric.

Proof:

Let \(a,b \in \mathbb{R} \) s.t. \(a=b \) and \(b=a \). Then clearly \(a=b \; \forall a,b \in \mathbb{R} \). \(\blacksquare \)

Yes \(R \) is transitive.

Proof:

Let \(a,b,c \in \mathbb{R} \) s.t. \(a=b \) and \(b=c \).

We shall show that \(aRc \).

Since \(a=b \) and \(b=c \) it follows that \(a=c \)

Thus \(aRc \). \(\blacksquare \)

Yes \(R \) is an equivalence relation.

Proof:

Since \(R \) is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, it is an equivalence relation.

Yes \(R \) is a partial order.

Proof:

Since \(R \) is a partial order since \(R \) is reflexive, antisymmetric and transitive.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Less than or equal to

Let \(S=\mathbb{R}\) and \(R\) be \(\leq\). Is the relation a) reflexive, b) symmetric, c) antisymmetric, d) transitive, e) an equivalence relation, f) a partial order.

Solution

Proof:

Counterexample:

It is true that , but it is not true that

.

Proof:

We will show that given and

that

.

Proof:

We will show that given and

that

.

5. No, is not an equivalence relation on

since it is not symmetric.

6. Yes, is a partial order on

since it is reflexive, antisymmetric and transitive.

Definition: Equivalence Class

Given an equivalence relation \( R \) over a set \( S, \) for any \(a \in S \) the equivalence class of a is the set \( [a]_R =\{ b \in S \mid a R b \} \), that is

\([a]_R \) is the set of all elements of S that are related to \(a\).

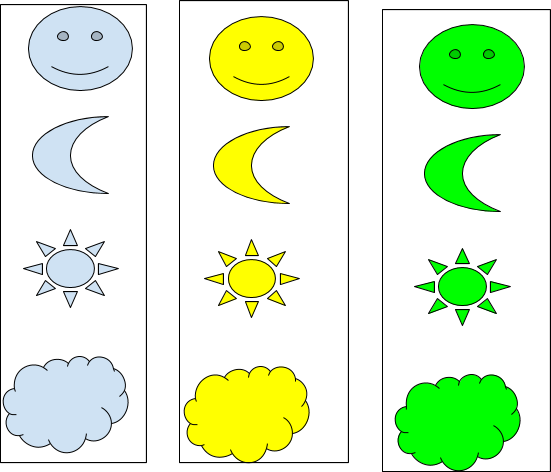

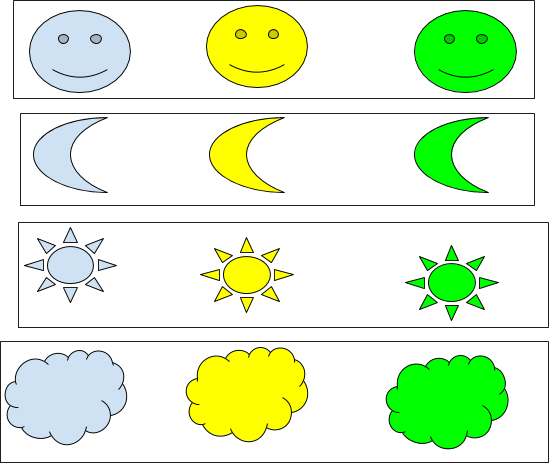

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Equivalence relation

Define a relation that two shapes are related iff they are the same color. Is this relation an equivalence relation?

Equivalence classes are:

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\):

Define a relation that two shapes are related iff they are similar. Is this relation an equivalence relation?

Equivalence classes are:

Let \(A\) be a nonempty set. A partition of \(A\) is a set of nonempty pairwise disjoint sets whose union is A.

Note

For every equivalence relation over a nonempty set \(S\), \(S\) has a partition.

Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\)

If \( \sim \) is an equivalence relation over a nonempty set \(S\). Then the set of all equivalence classes is denoted by \(\{[a]_{\sim}| a \in S\}\) forms a partition of \(S\).

This means

1. Either \([a] \cap [b] = \emptyset\) or \([a]=[b]\), for all \(a,b\in S\).

2. \(S= \cup_{a \in S} [a]\).

- Proof

-

Assume

is an equivalence relation on a nonempty set

.

Let

. If

, then we are done. Otherwise,

Let

be the common element between them.

Then

and

, which means that

and

.

Since

is an equivalence relation and

.

Since

and

(due to transitive property),

.

For the following examples, determine whether or not each of the following binary relations on the given set

is reflexive, symmetric, antisymmetric, or transitive. If a relation has a certain property, prove this is so; otherwise, provide a counterexample to show that it does not. If

is an equivalence relation, describe the equivalence classes of

.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\):

Let \(S = \{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9\}\). Define a relation \(R\) on \(A = S \times S \) by \((a, b) R (c, d)\) if and only if \(10a + b \leq 10c + d.\)

Solution

Proof:

Counter Example:

Since ,

is not symmetric on

.◻

Proof:

Thus is antisymmetric on

.◻

5. is transitive on .

Proof:

6. is not an equivalence relation since it is not reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\):

Let . Define a relation

on

, by

if and only if

Solution

Proof:

Clearly since

and a negative integer multiplied by a negative integer is a positive integer in

.

Since ,

is reflexive on

.◻

2. is symmetric on .

Proof:

Counter Example:

Since ,

is not antisymmetric on

.◻

Proof:

There are two cases to be examined:

Since in both possible cases

is transitive on

.◻

5. Since is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, it is an equivalence relation. Equivalence classes are

and

.

Note this is a partition since or

. So we have all the intersections are empty.

Recall:

Let \(m,n \in \mathbb{Z}\).

We say that \(m\) divides \(n\) (written as \(m|n\)) if \(n=mk\) for some \(k\in \mathbb{Z}\).

Let \(S= \mathbb{Z}, m\in \mathbb{Z}_+\). Define \(aRb\) if and only if \(m|(a-b), \forall a,b \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Note that \(m\) is a positive integer.

Let \(m=3\). Choose \(a=1\) and \(b=2\).

Are 1 and 2 related? i.e. does \(3|1-2\)? Does \(1-2=3k, k\in \mathbb{Z}\)? Since there is no integer \( k\) s.t. \(-1 = 3k\), ∴ \(1 \) is not related to \( 2\).

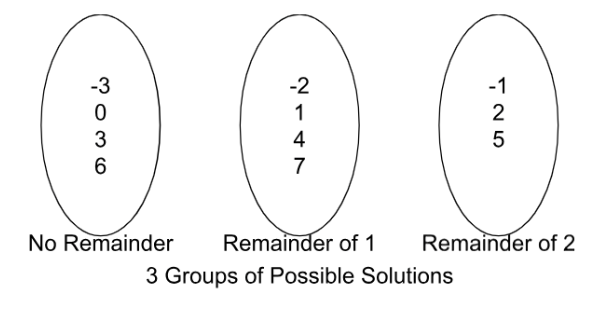

However, we can see that we have three groups, as shown in the image below:

Definition: Modulo

Let \(m\) \(\in\) \(\mathbb{Z_+}\).

\(a\) is congruent to \(b\) modulo \(m\) denoted as \( a \equiv b (mod \, n) \), if \(a\) and \(b\) have the remainder when they are divided by \(n\), for \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Properties

Let \(n \in \mathbb{Z_+}\). Then

Theorem 1 :

Two integers \(a \) and \(b\) are said to be congruent modulo \( n\), \(a \equiv b (mod \, n)\), if all of the following are true:

a) \(m\mid (a-b).\)

b) both \(a\) and \(b \) have the same remainder when divided by \(n.\)

c) \(a-b= kn\), for some \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\).

NOTE: Possible remainders of \( n\) are \(0, ..., n-1.\)

Reflexive Property

Theorem 2:

The relation " \(\equiv\) " over \(\mathbb{Z}\) is reflexive.

Proof: Let \(a \in \mathbb{Z} \).

Then \(a-a=0(n)\), and \( 0 \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Hence \(a \equiv a (mod \, n)\).

Thus congruence modulo n is Reflexive.

Symmetric Property

Theorem 3:

The relation " \(\equiv\) " over \(\mathbb{Z}\) is symmetric.

Proof: Let \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z} \) such that \(a \equiv b\) (mod n).

Then \(a-b=kn, \) for some \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Now \( b-a= (-k)n \) and \(-k \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Hence \(b \equiv a(mod \, n)\).

Thus the relation is symmetric.

Antisymmetric Property

Is the relation " \(\equiv\) " over \(\mathbb{Z}\) antisymmetric?

Counter Example: \(n\) is fixed

choose: \(a= n+1, b= 2n+1\), then

\(a \equiv b(mod \, n)\) and \( b \equiv a (mod \, n)\)

but \( a \ne b.\)

Thus the relation " \(\equiv\) "on \(\mathbb{Z}\) is not antisymmetric.

Transitive Property

Theorem 4 :

The relation " \(\equiv\) " over \(\mathbb{Z}\) is transitive.

Proof: Let \(a, b, c \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\), such that \(a \equiv b (mod n)\) and \(b \equiv c (mod n).\)

Then \(a=b+kn, k \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\) and \(b=c+hn, h \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\).

We shall show that \(a \equiv c (mod \, n)\).

Consider \(a=b+kn=(c+hn)+kn=c+(hn+kn)=c+(h+k)n, h+k \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\).

Hence \(a \equiv c (mod \, n)\).

Thus congruence modulo \(n\) is transitive.

Theorem 5:

The relation " \(\equiv\) " over \(\mathbb{Z}\) is an equivalence relation.

Modulo classes

Let . The relation \( \equiv \) on

by \( a \equiv b \) if and only if

, is an equivalence relation. The Classes of

have the following equivalence classes:

Example of writing equivalence classes:

Modulo Arithmetic

In this section, we will explore arithmetic operations in a modulo world.

Let \( n \in \mathbb{Z_+}\).

Theorem 5 :

Let \( a, b, c,d, \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(a \equiv b (mod\,n) \) and \(c \equiv d (mod\, n). \) Then \((a+c) \equiv (b+d)(mod\, n).\)

- Proof:

-

Let \(a, b, c, d \in\mathbb{Z}\), such that \(a \equiv b (mod\, n) \) and \(c \equiv d (mod \,n). \)

We shall show that \( (a+c) \equiv (b+d) (mod\, n).\)

Since \(a \equiv b (mod\, n) \) and \(c \equiv d (mod\, n), n \mid (a-b)\) and \(n \mid (c-d)\)

Thus \( a= b+nk, \) and \(c= d+nl,\) for \(k \) and \( l \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Consider\( (a+c) -( b+d)= a-b+c-d=n(k+l), k+l \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Hence \((a+c)\equiv (b+d) (mod \,n).\Box\)

Theorem 6:

![]()

Let \( a, b, c,d, \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(a \equiv b (mod \, n) \) and \(c \equiv d (mod \,n). \) Then \((ac) \equiv (bd) (mod \,n).\)

- Proof:

-

Let \(a, b, c, d \in \mathbb{Z}\), such that \(a \equiv b (mod\, n) \) and \(c \equiv d (mod \, n). \)

We shall show that \( (ac) \equiv (bd) (mod\, n).\)

Since \(a \equiv b (mod \,n) \) and \(c \equiv d (mod\, n), n \mid (a-b)\) and \(n \mid (c-d)\)

Thus \( a= b+nk, \) and \(c= d+nl,\) for \(k\) and \( l \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Consider \( (ac) -( bd)= ( b+nk) ( d+nl)-bd= bnl+dnk+n^2lk=n (bl+dk+nlk), \) where \((bl+dk+nlk) \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Hence \((ac) \equiv (bd) (mod \,n).\Box\)

Theorem 7:

Let \(a, b \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\) such that \(a \equiv b (mod \, n) \). Then \(a^2 \equiv b^2 (mod \, n).\)

- Proof:

-

Let \(a, b \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\), and n \(\in\) \(\mathbb{Z_+}\), such that \(a \equiv b (mod \, n).\)

We shall show that \(a^2 \equiv b^2 (mod \, n).\)

Since \( a \equiv b (mod \, n), n\mid (a-b).\)

Thus \( (a-b)= nx,\) where \(x \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\).

Consider \((a^2 - b^2) = (a+b)(a-b)=(a+b)(nx), = n(ax+bx), ax+bx \in \mathbb{Z}\).

Hence \(n \mid a^2 - b^2,\) therefore \(a^2 \equiv b^2 (mod \, n).\) \(\Box\)

Theorem 8:

Let \(a, b \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\) such that \(a \equiv b (mod \, n)\). Then \(a^m \equiv b^m (mod \, n)\), \(\forall \in\) \(\mathbb{Z}\).

- Proof:

-

Exercise.

By using the above result, we can solve many problems. Some of them are discussed below:

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): \( mod\, 3\) Arithmetic

Let \(n = 3\).

Addition

| + | [0] | [1] | [2] |

| [0] | [0] | [1] | [2] |

| [1] | [1] | [2] | [0] |

| [2] | [2] | [0] | [1] |

Multiplication

| x | [0] | [1] | [2] |

| [0] | [0] | [0] | [0] |

| [1] | [0] | [1] | [2] |

| [2] | [0] | [2] | [1] |

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): \( mod\, 4\) Arithmetic

Let \(n=4\).

| x | [0] | [1] | [2] | [3] |

| [0] | [0] | [0] | [0] | [0] |

| [1] | [0] | [1] | [2] | [3] |

| [2] | [0] | [2] | [0] | [2] |

| [3] | [0] | [3] | [2] | [1] |

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\):

Find the remainder when \((101)(103)(107)(109)\) is divided by \( 11.\)

- Answer

-

\(101 \equiv 2 (mod \, 11)\)

\(103 \equiv 4 (mod \, 11)\)

\(107 \equiv 8 (mod \, 11)\)

\(109 \equiv 10 (mod \,11)\).

Therefore,

\((101)(103)(107)(109) \equiv (2)(4)(8)(10) (mod \,11) \equiv 2 (mod \,11)\).

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\):

Find the remainder when\( 7^{1453}\) is divided by \( 8.\)

- Answer

-

\(7^0 \equiv 1 (mod \, 8)\)

\(7^1 \equiv 7 (mod \, 8)\)

\(7^2 \equiv 1 (mod \, 8)\)

\(7^3 \equiv 7 (mod \, 8)\),

As there is a consistent pattern emerging and we know that \(1453\) is odd, then \(7^{1453} \equiv 7 (mod \, 8)\). Thus the remainder is \(7.\)

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\):

Find the remainder when \(7^{2020}\) is divided by \(18.\)

- Answer

-

\(7^0 \equiv 1 (mod \, 18)\)

\(7^1 \equiv 7 (mod \, 18)\)

\(7^2 \equiv 13 (mod \, 18)\)

\(7^3 \equiv 1 (mod \, 18)\),

As there is a consistent pattern emerging and we know that \(2020=(673)3+1\), \(7^{2020}= 7^{(673)3+1}=\left( 7^3\right)^{673}7^1 \equiv 7 (mod \, 18).\) Thus the remainder is \(7.\)

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\):

Find the remainder when \( 26^{1453} \) is divided by \( 3.\)