3.4: Separable Differential Equations

- Page ID

- 10319

This page is a draft and is under active development.

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Separable Differential Equations

A first order differential equation is \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{separable}} \) if it can be written as

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.1}

h(y)y' = g(x),

\end{equation}

where the left side is a product of \(y'\) and a function of \(y\) and the right side is a function of \(x\). Rewriting a separable differential equation in this form is called \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{separation of variables}} \). In Section 2.1 we used separation of variables to solve homogeneous linear equations. In this section we'll apply this method to nonlinear equations.

To see how to solve \eqref{eq:3.5.1}, let's first assume that \(y\) is a solution. Let \(G(x)\) and \(H(y)\) be antiderivatives of \(g(x)\) and \(h(y)\); that is,

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.2}

H'(y) = h(y) \quad \mbox{and} \quad G'(x) = g(x)

\end{equation}

Then, from the chain rule,

\begin{eqnarray*}

{d \over dx} H(y(x)) = H'(y(x)) y'(x) = h(y) y'(x).

\end{eqnarray*}

Therefore \eqref{eq:3.5.1} is equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

{d \over dx} H(y(x)) = {d \over dx} G(x).

\end{eqnarray*}

Integrating both sides of this equation and combining the constants of integration yields

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.3}

H(y(x)) = G(x) + c.

\end{equation}

Although we derived this equation on the assumption that \(y\) is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.1}, we can now view it differently: Any differentiable function \(y\) that satisfies \eqref{eq:3.5.3} for some constant \(c\) is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.1}. To see this, we differentiate both sides of \eqref{eq:3.5.3}, using the chain rule on the left, to obtain

\begin{eqnarray*}

H'(y(x)) y'(x) + G'(x),

\end{eqnarray*}

which is equivalent to

\begin{eqnarray*}

h(y(x))y'(x)=g(x)

\end{eqnarray*}

because of \eqref{eq:3.5.2}.

In conclusion, to solve \eqref{eq:3.5.1} it suffices to find functions \(G=G(x)\) and \(H=H(y)\) that satisfy \eqref{eq:3.5.2}. Then any differentiable function \(y=y(x)\) that satisfies \eqref{eq:3.5.3} is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.1}.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Solve the equation

\begin{eqnarray*}

y'=x(1+y^2).

\end{eqnarray*}

- Answer

-

Separating variables yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

{y'\over 1+y^2}=x.

\end{eqnarray*}Integrating yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

\tan^{-1}y={x^2\over2}+c

\end{eqnarray*}Therefore

\begin{eqnarray*}

y=\tan\left({x^2\over2}+c\right).

\end{eqnarray*}

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

(a) Solve the equation

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.4}

y'=-{x\over y}.

\end{equation}

(b) Solve the initial value problem

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.5}

y'=-{x\over y}, \quad y(1)=1.

\end{equation}

(c) Solve the initial value problem

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.6}

y'=-{x\over y}, \quad y(1)=-2.

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

(a) Separating variables in \ref{eq:3.5.4} yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

yy'=-x.

\end{eqnarray*}Integrating yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

{y^2\over2}=-{x^2\over2}+c, \quad \mbox{ or, equivalently, } \quad x^2+y^2=2c.

\end{eqnarray*}The last equation shows that \(c\) must be positive if \(y\) is to be a solution of \ref{eq:3.5.4} on an open interval. Therefore we let \(2c=a^2\) (with \(a > 0\)) and rewrite the last equation as

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.7}

x^2+y^2=a^2.

\end{equation}This equation has two differentiable solutions for \(y\) in terms of \(x\):

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.8}

y=\phantom{-} \sqrt{a^2-x^2}, \quad -a < x < a,

\end{equation}and

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.9}

y= - \sqrt{a^2-x^2}, \quad -a < x < a.

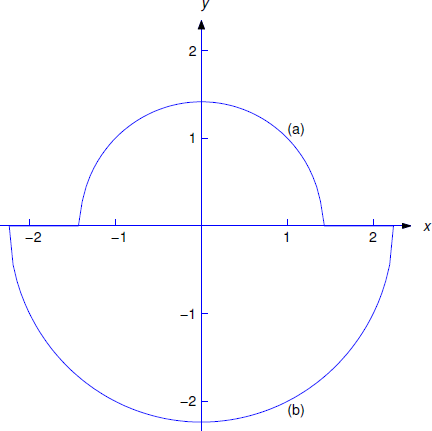

\end{equation}The solution curves defined by \ref{eq:3.5.8} are semicircles above the \(x\)-axis and those defined by \ref{eq:3.5.9} are semicircles below the \(x\)-axis (Figure \(3.5.1\)).

(b) The solution of \ref{eq:3.5.5} is positive when \(x=1\); hence, it is of the form \ref{eq:3.5.8}. Substituting \(x=1\) and \(y=1\) into \ref{eq:3.5.7} to satisfy the initial condition yields \(a^2=2\); hence, the solution of \ref{eq:3.5.5} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

y=\sqrt{2-x^2}, \quad - \sqrt{2}< x < \sqrt{2}.

\end{eqnarray*}(c) The solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.6} is negative when \(x=1\) and is therefore of the form \eqref{eq:3.5.9}. Substituting \(x=1\) and \(y=-2\) into \eqref{eq:3.5.7} to satisfy the initial condition yields \(a^2=5\). Hence, the solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.6} is

\begin{eqnarray*}

y=- \sqrt{5-x^2}, \quad -\sqrt{5} < x < \sqrt{5}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): (a) \(y=\sqrt{2-x^{2}}\), \(-\sqrt{2}<x<\sqrt{2}\); (b) \(y=-\sqrt{5-x^{2}}\), \(-\sqrt{5}<x<\sqrt{5}\)

Implicit Solutions of Separable Equations

In Examples \((3.5.1)\) and \((3.5.2)\) we were able to solve the equation \(H(y)=G(x)+c\) to obtain explicit formulas for solutions of the given separable differential equations. As we'll see in the next example, this isn't always possible. In this situation we must broaden our definition of a solution of a separable equation. The next theorem provides the basis for this modification. We omit the proof, which requires a result from advanced calculus called as the \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{implicit function theorem}} \).

Theorem \(\PageIndex{1}\): Implicit function theorem

Suppose \(g=g(x)\) is continuous on \((a,b)\) and \(h=h(y)\) are continuous on \((c,d).\) Let \(G\) be an antiderivative of \(g\) on \((a,b)\) and let \(H\) be an antiderivative of \(h\) on \((c,d).\) Let \(x_0\) be an arbitrary point in \((a,b),\) let \(y_0\) be a point in \((c,d)\) such that \(h(y_0)\ne0,\) and define

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.10}

c=H(y_0)-G(x_0).

\end{equation}

Then there's a function \(y=y(x)\) defined on some open interval \((a_1,b_1),\) where \(a\le a_1<x_0<b_1\le b,\) such that \(y(x_0)=y_0\) and

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.11}

H(y)=G(x)+c

\end{equation}

for \(a_1<x<b_1\). Therefore \(y\) is a solution of the initial value problem

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.12}

h(y)y'=g(x),\quad y(x_0)=x_0.

\end{equation}

It's convenient to say that \eqref{eq:3.5.11} with \(c\) arbitrary is an \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{implicit solution}} \) of \(h(y)y'=g(x)\). Curves defined by \eqref{eq:3.5.11} are integral curves of \(h(y)y'=g(x)\). If \(c\) satisfies \eqref{eq:3.5.10}, we'll say that \eqref{eq:3.5.11} is an \( \textcolor{blue}{\mbox{implicit solution of the initial value problem}} \) \eqref{eq:3.5.12}. However, keep these points in mind:

a. For some choices of \(c\) there may not be any differentiable functions \(y\) that satisfy \eqref{eq:3.5.11}.\

b. The function \(y\) in \eqref{eq:3.5.11} (not \eqref{eq:3.5.11} itself) is a solution of \(h(y)y'=g(x)\).

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

(a) Find implicit solutions of

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.13}

y'={2x+1\over5y^4+1}.

\end{equation}

(b) Find an implicit solution of

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.14}

y'={2x+1\over5y^4+1},\quad y(2)=1.

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

(a) Separating variables yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

(5y^4+1)y'=2x+1.

\end{eqnarray*}Integrating yields the implicit solution

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.15}

y^5+y=x^2+x+ c.

\end{equation}of \eqref{eq:3.5.13}.

(b) Imposing the initial condition \(y(2)=1\) in \eqref{eq:3.5.15} yields \(1+1=4+2+c\), so \(c=-4\). Therefore

\begin{eqnarray*}

y^5+y=x^2+x-4

\end{eqnarray*}is an implicit solution of the initial value problem \eqref{eq:3.5.14}. Although more than one differentiable function \(y=y(x)\) satisfies \ref{eq:3.5.13}) near \(x=1\), it can be shown that there's only one such function that satisfies the initial condition \(y(1)=2\).

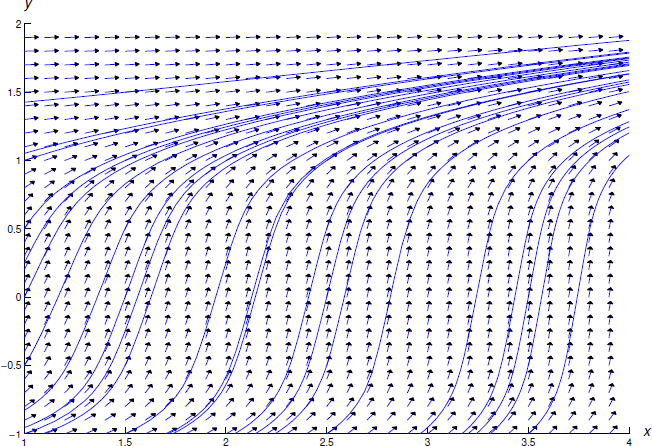

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows a direction field and some integral curves for \eqref{eq:3.5.13}.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): A direction field and integral curves for \(y'= {\frac{2x+1}{5y^{4}+1}}\)

Constant Solutions of Separable Equations

An equation of the form

\begin{eqnarray*}

y'=g(x)p(y)

\end{eqnarray*}

is separable, since it can be rewritten as

\begin{eqnarray*}

{1\over p(y)}y'=g(x).

\end{eqnarray*}

However, the division by \(p(y)\) is not legitimate if \(p(y)=0\) for some values of \(y\). The next two examples show how to deal with this problem.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Find all solutions of

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.16}

y'=2xy^2.

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

Here we must divide by \(p(y)=y^2\) to separate variables. This isn't legitimate if \(y\) is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.16} that equals zero for some value of \(x\). One such solution can be found by inspection: \(y \equiv 0\). Now suppose \(y\) is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.16} that isn't identically zero. Since \(y\) is continuous there must be an interval on which \(y\) is never zero. Since division by \(y^2\) is legitimate for \(x\) in this interval, we can separate variables in \eqref{eq:3.5.16} to obtain

\begin{eqnarray*}

{y'\over y^2}=2x.

\end{eqnarray*}Integrating this yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

-{1\over y}=x^2+c,

\end{eqnarray*}which is equivalent to

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.17}

y=-{1\over x^2+c}.

\end{equation}We've now shown that if \(y\) is a solution of \ref{eq:3.5.16} that is not identically zero, then \(y\) must be of the form \ref{eq:3.5.17}. By substituting \ref{eq:3.5.17} into \ref{eq:3.5.16}, you can verify that \ref{eq:3.5.17} is a solution of \ref{eq:3.5.16}. Thus, solutions of \ref{eq:3.5.16} are \(y\equiv0\) and the functions of the form \ref{eq:3.5.17}. Note that the solution \(y\equiv0\) isn't of the form \ref{eq:3.5.17} for any value of \(c\).

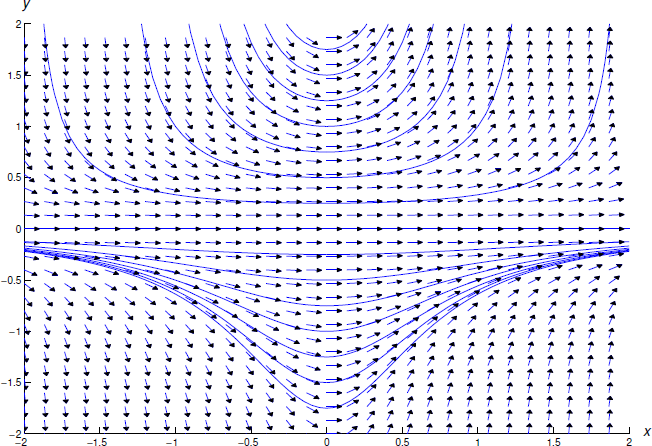

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows aa direction field and some integral curves for \ref{eq:3.5.16}

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): A direction field and integral curves for \(y'=2xy^{2}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Find all solutions of

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.18}

y'={1\over2}x(1-y^2).

\end{equation}

- Answer

-

Here we must divide by \(p(y)=1-y^2\) to separate variables. This isn't legitimate if \(y\) is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.18} that equals \(\pm1\) for some value of \(x\). Two such solutions can be found by inspection: \(y \equiv 1\) and \(y\equiv-1\). Now suppose \(y\) is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.18} such that \(1-y^2\) isn't identically zero. Since \(1-y^2\) is continuous there must be an interval on which \(1-y^2\) is never zero. Since division by \(1-y^2\) is legitimate for \(x\) in this interval, we can separate variables in \eqref{eq:3.5.18} to obtain

\begin{eqnarray*}

{2y'\over y^2-1}=-x.

\end{eqnarray*}A partial fraction expansion on the left yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[{1\over y-1}-{1\over y+1}\right]y'=-x,

\end{eqnarray*}and integrating yields

\begin{eqnarray*}

\ln\left|{y-1\over y+1}\right|=-{x^2\over2}+k;

\end{eqnarray*}hence,

\begin{eqnarray*}

\left|{y-1\over y+1}\right|=e^ke^{-x^2/2}.

\end{eqnarray*}Since \(y(x)\ne\pm1\) for \(x\) on the interval under discussion, the quantity \((y-1)/(y+1)\) can't change sign in this interval. Therefore we can rewrite the last equation as

\begin{eqnarray*}

{y-1\over y+1}=ce^{-x^2/2},

\end{eqnarray*}where \(c=\pm e^k\), depending upon the sign of \((y-1)/(y+1)\) on the interval. Solving for \(y\) yields

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.19}

y={1+ce^{-x^2/2}\over 1-ce^{-x^2/2}}.

\end{equation}We've now shown that if \(y\) is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.18} that is not identically equal to \(\pm1\), then \(y\) must be as in \eqref{eq:3.5.19}. By substituting \eqref{eq:3.5.19} into \eqref{eq:3.5.18} you can verify that \eqref{eq:3.5.19} is a solution of \eqref{eq:3.5.18}. Thus, the solutions of \eqref{eq:3.5.18} are \(y\equiv1\), \(y\equiv-1\) and the functions of the form \eqref{eq:3.5.19}. Note that the constant solution \(y \equiv 1\) can be obtained from this formula by taking \(c=0\); however, the other constant solution, \(y \equiv -1\), can't be obtained in this way.

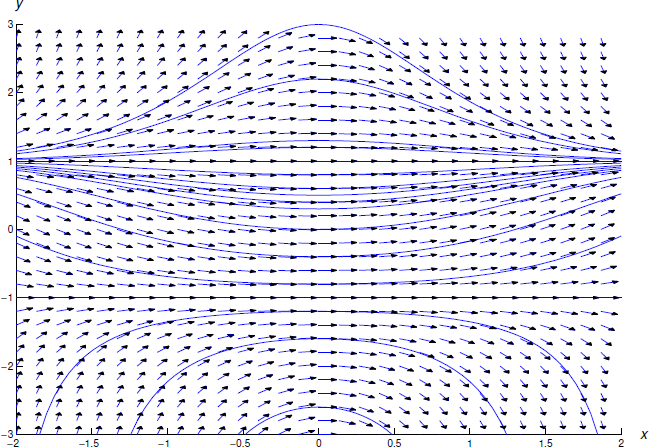

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows a direction field and some integrals for \eqref{eq:3.5.18}.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): A direction field and integral curves for \(y'= {\frac{x(1-y^2)}{2}}\)

Differences Between Linear and Nonlinear Equations

Theorem \(3.4.2\) states that if \(p\) and \(f\) are continuous on \((a,b)\) then every solution of

\begin{eqnarray*}

y'+p(x)y=f(x)

\end{eqnarray*}

on \((a,b)\) can be obtained by choosing a value for the constant \(c\) in the general solution, and if \(x_0\) is any point in \((a,b)\) and \(y_0\) is arbitrary, then the initial value problem

\begin{eqnarray*}

y'+p(x)y=f(x),\quad y(x_0)=y_0

\end{eqnarray*}

has a solution on \((a,b)\).

The not true for nonlinear equations. First, we saw in Examples \((3.5.4)\) and \((3.5.5)\) that a nonlinear equation may have solutions that can't be obtained by choosing a specific value of a constant appearing in a one-parameter family of solutions. Second, it is in general impossible to determine the interval of validity of a solution to an initial value problem for a nonlinear equation by simply examining the equation, since the interval of validity may depend on the initial condition. For instance, in Example \((3.5.2)\) we saw that the solution of

\begin{eqnarray*}

{dy\over dx}=-{x\over y},\quad y(x_0)=y_0

\end{eqnarray*}

is valid on \((-a,a)\), where \(a=\sqrt{x_0^2+y_0^2}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Solve the initial value problem

\begin{eqnarray*}

y'=2xy^2, \quad y(0)=y_0

\end{eqnarray*}

and determine the interval of validity of the solution.

- Answer

-

First suppose \(y_0\ne0\). From Example \((3.5.4)\), we know that \(y\) must be of the form

\begin{equation} \label{eq:3.5.20}

y=-{1\over x^2+c}.

\end{equation}Imposing the initial condition shows that \(c=-1/y_0\). Substituting this into \eqref{eq:3.5.20} and rearranging terms yields the solution

\begin{eqnarray*}

y= {y_0\over 1-y_0x^2}.

\end{eqnarray*}This is also the solution if \(y_0=0\). If \(y_0<0\), the denominator isn't zero for any value of \(x\), so the the solution is valid on \((-\infty,\infty)\). If \(y_0>0\), the solution is valid only on \((-1/\sqrt{y_0},1/\sqrt{y_0})\).