6.2: Volumes Using Cylindrical Shells

- Page ID

- 8163

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Calculate the volume of a solid of revolution by using the method of cylindrical shells.

- Compare the different methods for calculating a volume of revolution.

In this section, we examine the method of cylindrical shells, the final method for finding the volume of a solid of revolution. We can use this method on the same kinds of solids as the disk method or the washer method; however, with the disk and washer methods, we integrate along the coordinate axis parallel to the axis of revolution. With the method of cylindrical shells, we integrate along the coordinate axis perpendicular to the axis of revolution. The ability to choose which variable of integration we want to use can be a significant advantage with more complicated functions. Also, the specific geometry of the solid sometimes makes the method of using cylindrical shells more appealing than using the washer method. In the last part of this section, we review all the methods for finding volume that we have studied and lay out some guidelines to help you determine which method to use in a given situation.

The Method of Cylindrical Shells

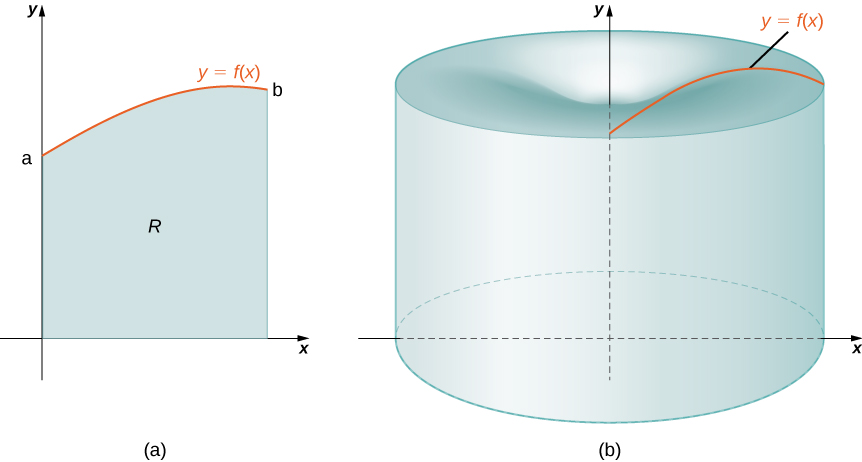

Again, we are working with a solid of revolution. As before, we define a region \(R\), bounded above by the graph of a function \(y=f(x)\), below by the \(x\)-axis, and on the left and right by the lines \(x=a\) and \(x=b\), respectively, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1a}\). We then revolve this region around the \(y\)-axis, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1b}\). Note that this is different from what we have done before. Previously, regions defined in terms of functions of \(x\) were revolved around the \(x\)-axis or a line parallel to it.

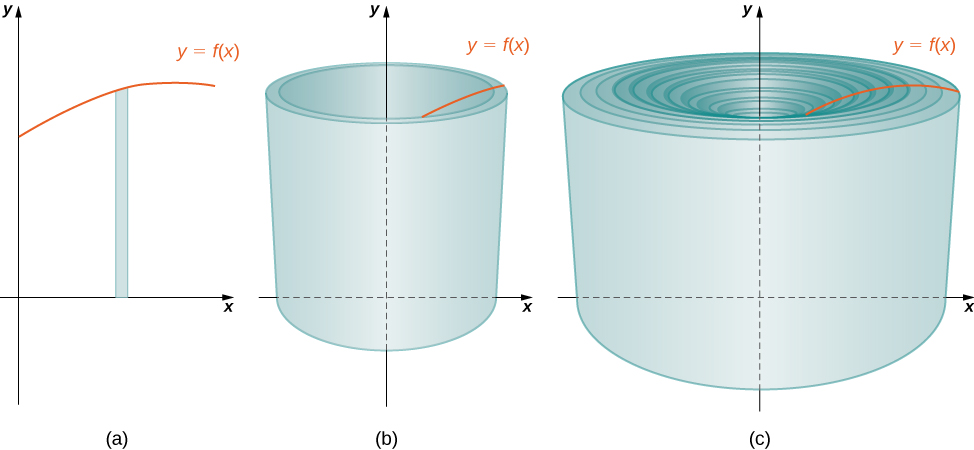

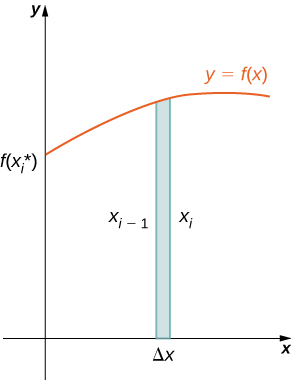

As we have done many times before, partition the interval \([a,b]\) using a regular partition, \(P={x_0,x_1,…,x_n}\) and, for \(i=1,2,…,n\), choose a point \(x^∗_i∈[x_{i−1},x_i]\). Then, construct a rectangle over the interval \([x_{i−1},x_i]\) of height \(f(x^∗_i)\) and width \(Δx\). A representative rectangle is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2a}\). When that rectangle is revolved around the \(y\)-axis, instead of a disk or a washer, we get a cylindrical shell, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

To calculate the volume of this shell, consider Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

The shell is a cylinder, so its volume is the cross-sectional area multiplied by the height of the cylinder. The cross-sections are annuli (ring-shaped regions—essentially, circles with a hole in the center), with outer radius \(x_i\) and inner radius \(x_{i−1}\). Thus, the cross-sectional area is \(πx^2_i−πx^2_{i−1}\). The height of the cylinder is \(f(x^∗_i).\) Then the volume of the shell is

\[ \begin{align*} V_{shell} =f(x^∗_i)(π\,x^2_{i}−π\,x^2_{i−1}) \\[4pt] =π\,f(x^∗_i)(x^2_i−x^2_{i−1}) \\[4pt] =π\,f(x^∗_i)(x_i+x_{i−1})(x_i−x_{i−1}) \\[4pt] =2π\,f(x^∗_i)\left(\dfrac {x_i+x_{i−1}}{2}\right)(x_i−x_{i−1}). \end{align*}\]

Note that \(x_i−x_{i−1}=Δx,\) so we have

\[V_{shell}=2π\,f(x^∗_i)\left(\dfrac {x_i+x_{i−1}}{2}\right)\,Δx. \nonumber \]

Furthermore, \(\dfrac {x_i+x_{i−1}}{2}\) is both the midpoint of the interval \([x_{i−1},x_i]\) and the average radius of the shell, and we can approximate this by \(x^∗_i\). We then have

\[V_{shell}≈2π\,f(x^∗_i)x^∗_i\,Δx. \nonumber \]

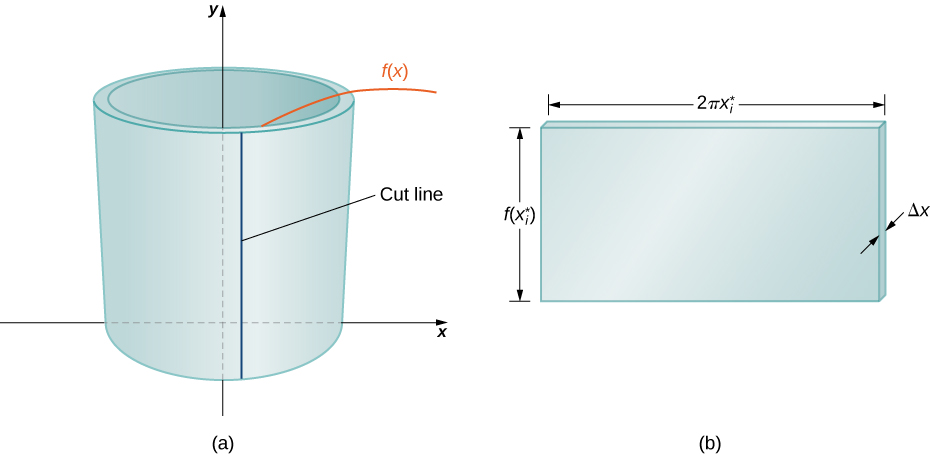

Another way to think of this is to think of making a vertical cut in the shell and then opening it up to form a flat plate (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

In reality, the outer radius of the shell is greater than the inner radius, and hence the back edge of the plate would be slightly longer than the front edge of the plate. However, we can approximate the flattened shell by a flat plate of height \(f(x^∗_i)\), width \(2πx^∗_i\), and thickness \(Δx\) (Figure). The volume of the shell, then, is approximately the volume of the flat plate. Multiplying the height, width, and depth of the plate, we get

\[V_{shell}≈f(x^∗_i)(2π\,x^∗_i)\,Δx, \nonumber \]

which is the same formula we had before.

To calculate the volume of the entire solid, we then add the volumes of all the shells and obtain

\[V≈\sum_{i=1}^n(2π\,x^∗_if(x^∗_i)\,Δx). \nonumber \]

Here we have another Riemann sum, this time for the function \(2π\,x\,f(x).\) Taking the limit as \(n→∞\) gives us

\[V=\lim_{n→∞}\sum_{i=1}^n(2π\,x^∗_if(x^∗_i)\,Δx)=\int ^b_a(2π\,x\,f(x))\,dx. \nonumber \]

This leads to the following rule for the method of cylindrical shells.

Let \(f(x)\) be continuous and nonnegative. Define \(R\) as the region bounded above by the graph of \(f(x)\), below by the \(x\)-axis, on the left by the line \(x=a\), and on the right by the line \(x=b\). Then the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(R\) around the \(y\)-axis is given by

\[V=\int ^b_a(2π\,x\,f(x))\,dx. \nonumber \]

Now let’s consider an example.

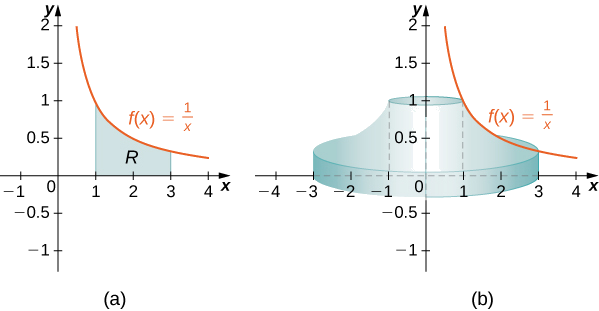

Define \(R\) as the region bounded above by the graph of \(f(x)=1/x\) and below by the \(x\)-axis over the interval \([1,3]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(R\) around the \(y\)-axis.

Solution

First we must graph the region \(R\) and the associated solid of revolution, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) (c) Visualizing the solid of revolution with CalcPlot3D.

Then the volume of the solid is given by

\[ \begin{align*} V =\int ^b_a(2π\,x\,f(x))\,dx \\ =\int ^3_1\left(2π\,x\left(\dfrac {1}{x}\right)\right)\,dx \\ =\int ^3_12π\,dx\\ =2π\,x\bigg|^3_1=4π\,\text{units}^3. \end{align*}\]

Define R as the region bounded above by the graph of \(f(x)=x^2\) and below by the \(x\)-axis over the interval \([1,2]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(R\) around the \(y\)-axis.

- Hint

-

Use the procedure from Example \(\PageIndex{1}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{15π}{2} \, \text{units}^3 \)

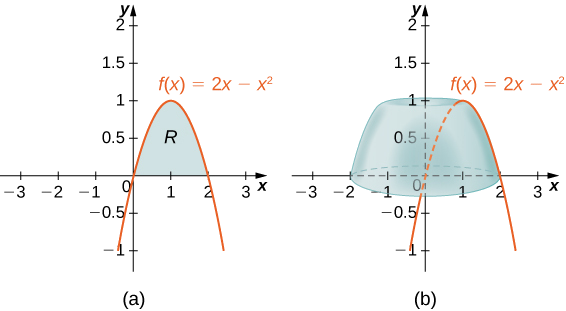

Define \(R\) as the region bounded above by the graph of \(f(x)=2x−x^2\) and below by the \(x\)-axis over the interval \([0,2]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(R\) around the \(y\)-axis.

Solution

First graph the region \(R\) and the associated solid of revolution, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Then the volume of the solid is given by

\[\begin{align*} V =\int ^b_a(2π\,x\,f(x))\,dx \\ =\int ^2_0(2π\,x(2x−x^2))\,dx \\ = 2π\int ^2_0(2x^2−x^3)\,dx \\ =2π \left. \left[\dfrac {2x^3}{3}−\dfrac {x^4}{4}\right]\right|^2_0 \\ =\dfrac {8π}{3}\,\text{units}^3 \end{align*}\]

Define \(R\) as the region bounded above by the graph of \(f(x)=3x−x^2\) and below by the \(x\)-axis over the interval \([0,2]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(R\) around the \(y\)-axis.

- Hint

-

Use the process from Example \(\PageIndex{2}\).

- Answer

-

\(8π \, \text{units}^3 \)

As with the disk method and the washer method, we can use the method of cylindrical shells with solids of revolution, revolved around the \(x\)-axis, when we want to integrate with respect to \(y\). The analogous rule for this type of solid is given here.

Let \(g(y)\) be continuous and nonnegative. Define \(Q\) as the region bounded on the right by the graph of \(g(y)\), on the left by the \(y\)-axis, below by the line \(y=c\), and above by the line \(y=d\). Then, the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(Q\) around the \(x\)-axis is given by

\[V=\int ^d_c(2π\,y\,g(y))\,dy. \nonumber \]

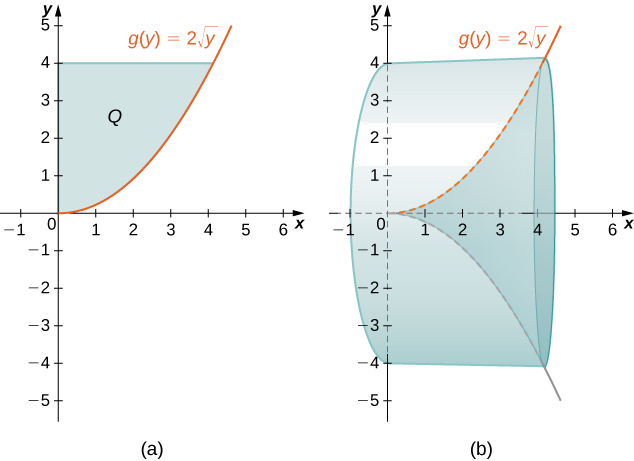

Define \(Q\) as the region bounded on the right by the graph of \(g(y)=2\sqrt{y}\) and on the left by the \(y\)-axis for \(y∈[0,4]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(Q\) around the \(x\)-axis.

Solution

First, we need to graph the region \(Q\) and the associated solid of revolution, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

Label the shaded region \(Q\). Then the volume of the solid is given by

\[ \begin{align*} V =\int ^d_c(2π\,y\,g(y))\,dy \\ =\int ^4_0(2π\,y(2\sqrt{y}))\,dy \\ =4π\int ^4_0y^{3/2}\,dy \\ =4π\left[\dfrac {2y^{5/2}}{5}\right]∣^4_0 \\ =\dfrac {256π}{5}\, \text{units}^3 \end{align*}\]

Define \(Q\) as the region bounded on the right by the graph of \(g(y)=3/y\) and on the left by the \(y\)-axis for \(y∈[1,3]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(Q\) around the \(x\)-axis.

- Hint

-

Use the process from Example \(\PageIndex{3}\).

- Answer

-

\(12π\) units3

For the next example, we look at a solid of revolution for which the graph of a function is revolved around a line other than one of the two coordinate axes. To set this up, we need to revisit the development of the method of cylindrical shells. Recall that we found the volume of one of the shells to be given by

\[\begin{align*} V_{shell} =f(x^∗_i)(π\,x^2_i−π\,x^2_{i−1}) \\[4pt] =π\,f(x^∗_i)(x^2_i−x^2_{i−1}) \\[4pt] =π\,f(x^∗_i)(x_i+x_{i−1})(x_i−x_{i−1}) \\[4pt] =2π\,f(x^∗_i)\left(\dfrac {x_i+x_{i−1}}{2}\right)(x_i−x_{i−1}).\end{align*}\]

This was based on a shell with an outer radius of \(x_i\) and an inner radius of \(x_{i−1}\). If, however, we rotate the region around a line other than the \(y\)-axis, we have a different outer and inner radius. Suppose, for example, that we rotate the region around the line \(x=−k,\) where \(k\) is some positive constant. Then, the outer radius of the shell is \(x_i+k\) and the inner radius of the shell is \(x_{i−1}+k\). Substituting these terms into the expression for volume, we see that when a plane region is rotated around the line \(x=−k,\) the volume of a shell is given by

\[\begin{align*} V_{shell} =2π\,f(x^∗_i)(\dfrac {(x_i+k)+(x_{i−1}+k)}{2})((x_i+k)−(x_{i−1}+k)) \\[4pt] =2π\,f(x^∗_i)\left(\left(\dfrac {x_i+x_{i−2}}{2}\right)+k\right)Δx.\end{align*}\]

As before, we notice that \(\dfrac {x_i+x_{i−1}}{2}\) is the midpoint of the interval \([x_{i−1},x_i]\) and can be approximated by \(x^∗_i\). Then, the approximate volume of the shell is

\[V_{shell}≈2π(x^∗_i+k)f(x^∗_i)Δx. \nonumber \]

The remainder of the development proceeds as before, and we see that

\[V=\int ^b_a(2π(x+k)f(x))dx. \nonumber \]

We could also rotate the region around other horizontal or vertical lines, such as a vertical line in the right half plane. In each case, the volume formula must be adjusted accordingly. Specifically, the \(x\)-term in the integral must be replaced with an expression representing the radius of a shell. To see how this works, consider the following example.

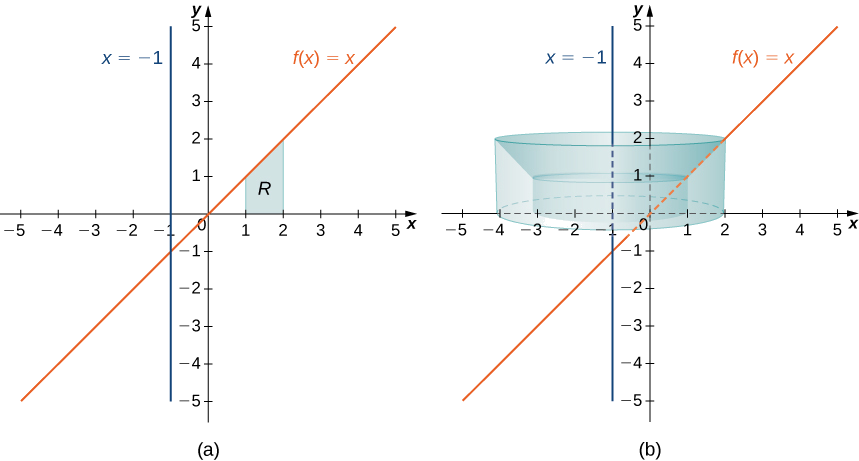

Define \(R\) as the region bounded above by the graph of \(f(x)=x\) and below by the \(x\)-axis over the interval \([1,2]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(R\) around the line \(x=−1.\)

Solution

First, graph the region \(R\) and the associated solid of revolution, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\).

Note that the radius of a shell is given by \(x+1\). Then the volume of the solid is given by

\[\begin{align*} V =\int ^2_1 2π(x+1)f(x)\, dx \\ =\int ^2_1 2π(x+1)x \, dx=2π\int ^2_1 x^2+x \, dx \\ =2π \left[\dfrac{x^3}{3}+\dfrac{x^2}{2}\right]\bigg|^2_1 \\ =\dfrac{23π}{3} \, \text{units}^3 \end{align*}\]

Define \(R\) as the region bounded above by the graph of \(f(x)=x^2\) and below by the \(x\)-axis over the interval \([0,1]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(R\) around the line \(x=−2\).

- Hint

-

Use the process from Example \(\PageIndex{4}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac {11π}{6}\) units3

For our final example in this section, let’s look at the volume of a solid of revolution for which the region of revolution is bounded by the graphs of two functions.

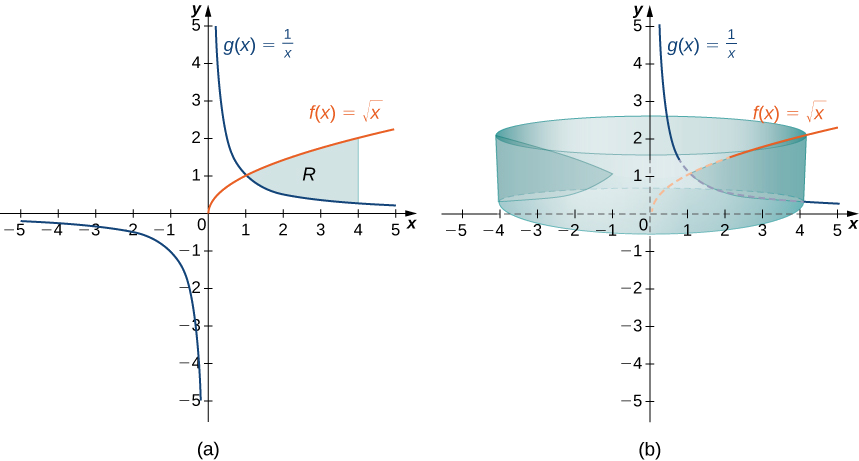

Define \(R\) as the region bounded above by the graph of the function \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\) and below by the graph of the function \(g(x)=1/x\) over the interval \([1,4]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution generated by revolving \(R\) around the \(y\)-axis.

Solution

First, graph the region \(R\) and the associated solid of revolution, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\).

Note that the axis of revolution is the \(y\)-axis, so the radius of a shell is given simply by \(x\). We don’t need to make any adjustments to the x-term of our integrand. The height of a shell, though, is given by \(f(x)−g(x)\), so in this case we need to adjust the \(f(x)\) term of the integrand. Then the volume of the solid is given by

\[\begin{align*} V =\int ^4_1(2π\,x(f(x)−g(x)))\,dx \\[4pt] = \int ^4_1(2π\,x(\sqrt{x}−\dfrac {1}{x}))\,dx=2π\int ^4_1(x^{3/2}−1)dx \\[4pt] = 2π\left[\dfrac {2x^{5/2}}{5}−x\right]\bigg|^4_1=\dfrac {94π}{5} \, \text{units}^3. \end{align*}\]

Define \(R\) as the region bounded above by the graph of \(f(x)=x\) and below by the graph of \(g(x)=x^2\) over the interval \([0,1]\). Find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving \(R\) around the \(y\)-axis.

- Hint

-

Hint: Use the process from Example \(\PageIndex{5}\).

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac {π}{6}\) units3

Which Method Should We Use?

We have studied several methods for finding the volume of a solid of revolution, but how do we know which method to use? It often comes down to a choice of which integral is easiest to evaluate. Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) describes the different approaches for solids of revolution around the \(x\)-axis. It’s up to you to develop the analogous table for solids of revolution around the \(y\)-axis.

![This figure is a table comparing the different methods for finding volumes of solids of revolution. The columns in the table are labeled “comparison”, “disk method”, “washer method”, and “shell method”. The rows are labeled “volume formula”, “solid”, “interval to partition”, “rectangles”, “typical region”, and “rectangle”. In the disk method column, the formula is given as the definite integral from a to b of pi times [f(x)]^2. The solid has no cavity in the center, the partition is [a,b], rectangles are vertical, and the typical region is a shaded region above the x-axis and below the curve of f(x). In the washer method column, the formula is given as the definite integral from a to b of pi times [f(x)]^2-[g(x)]^2. The solid has a cavity in the center, the partition is [a,b], rectangles are vertical, and the typical region is a shaded region above the curve of g(x) and below the curve of f(x). In the shell method column, the formula is given as the definite integral from c to d of 2pi times yg(y). The solid is with or without a cavity in the center, the partition is [c,d] rectangles are horizontal, and the typical region is a shaded region above the x-axis and below the curve of g(y).](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/2735/CNX_Calc_Figure_06_03_009.jpeg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=974&height=732)

Let’s take a look at a couple of additional problems and decide on the best approach to take for solving them.

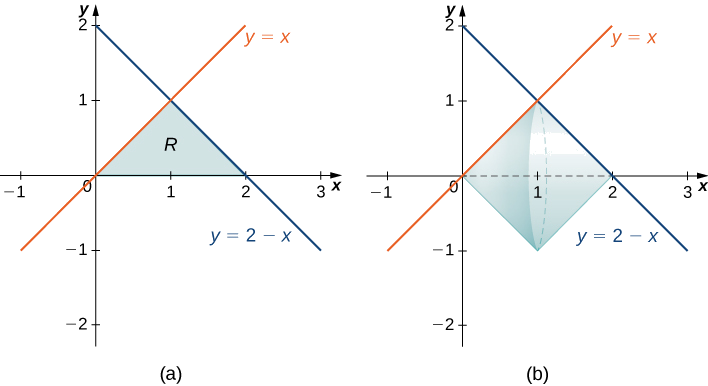

For each of the following problems, select the best method to find the volume of a solid of revolution generated by revolving the given region around the \(x\)-axis, and set up the integral to find the volume (do not evaluate the integral).

- The region bounded by the graphs of \(y=x, y=2−x,\) and the \(x\)-axis.

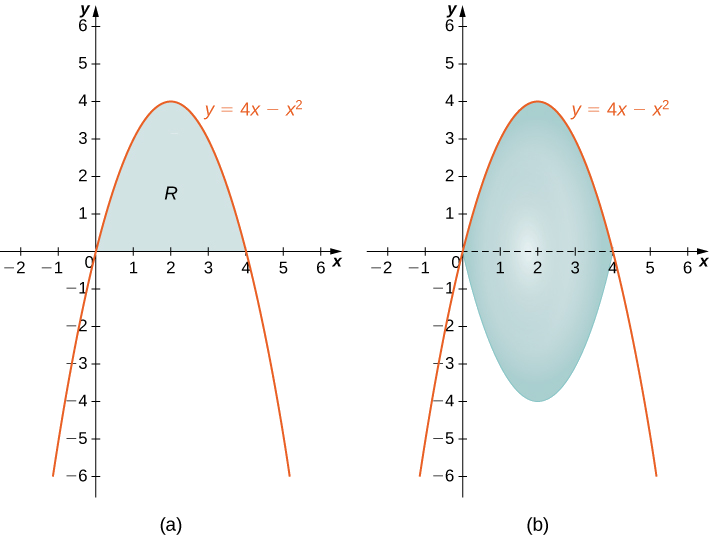

- The region bounded by the graphs of \(y=4x−x^2\) and the \(x\)-axis.

Solution

a.

First, sketch the region and the solid of revolution as shown.

Looking at the region, if we want to integrate with respect to \(x\), we would have to break the integral into two pieces, because we have different functions bounding the region over \([0,1]\) and \([1,2]\). In this case, using the disk method, we would have

\[V=\int ^1_0 π\,x^2\,dx+\int ^2_1 π(2−x)^2\,dx. \nonumber \]

If we used the shell method instead, we would use functions of y to represent the curves, producing

\[V=\int ^1_0 2π\,y[(2−y)−y] \,dy=\int ^1_0 2π\,y[2−2y]\,dy. \nonumber \]

Neither of these integrals is particularly onerous, but since the shell method requires only one integral, and the integrand requires less simplification, we should probably go with the shell method in this case.

b.

First, sketch the region and the solid of revolution as shown.

Looking at the region, it would be problematic to define a horizontal rectangle; the region is bounded on the left and right by the same function. Therefore, we can dismiss the method of shells. The solid has no cavity in the middle, so we can use the method of disks. Then

\[V=\int ^4_0π\left(4x−x^2\right)^2\,dx \nonumber \]

Select the best method to find the volume of a solid of revolution generated by revolving the given region around the \(x\)-axis, and set up the integral to find the volume (do not evaluate the integral): the region bounded by the graphs of \(y=2−x^2\) and \(y=x^2\).

- Hint

-

Sketch the region and use Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) to decide which integral is easiest to evaluate.

- Answer

-

Use the method of washers; \[V=\int ^1_{−1}π\left[\left(2−x^2\right)^2−\left(x^2\right)^2\right]\,dx \nonumber \]

Key Concepts

- The method of cylindrical shells is another method for using a definite integral to calculate the volume of a solid of revolution. This method is sometimes preferable to either the method of disks or the method of washers because we integrate with respect to the other variable. In some cases, one integral is substantially more complicated than the other.

- The geometry of the functions and the difficulty of the integration are the main factors in deciding which integration method to use.

Key Equations

- Method of Cylindrical Shells

\(\displaystyle V=\int ^b_a\left(2π\,x\,f(x)\right)\,dx\)

Glossary

- method of cylindrical shells

- a method of calculating the volume of a solid of revolution by dividing the solid into nested cylindrical shells; this method is different from the methods of disks or washers in that we integrate with respect to the opposite variable