16.8: The Divergence Theorem and a Unified Theory

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

When we looked at Green's Theorem, we saw that there was a relationship between a region and the curve that encloses it. This gave us the relationship between the line integral and the double integral. Now consider the following theorem:

Let Q be a solid region bounded by a closed surface oriented with outward pointing unit normal vector n, and let F be a differentiable vector field (i.e., components have continuous partial derivatives). Then

∬SF⋅ndS=∭Q∇⋅Fdv.

Find

∬SF⋅Nds

where

F(x,y,z)=y2ˆi+ex(1−cos(x2+z2)ˆj+(x+z)ˆk

and S is the unit sphere centered at the point (1,4,6) with outwardly pointing normal vector.

Solution

This seemingly difficult problem turns out to be quite easy once we have the divergence theorem. We have

∇⋅F=0+0+1=1

Now recall that a triple integral of the function 1 is the volume of the solid. Since the solid is a sphere of radius 1 we get 43π.

As usual, we will make some simplifying remarks and then prove part of the divergence theorem. We assume that the solid is bounded below by z=g1(x,y) and above by z=g2(x,y).

Notice that the outward pointing normal vector is upward on the top surface and downward for the bottom region. We also note that the divergence theorem can be written as

∬SF⋅NdS=∬S(Mˆi⋅N+Nˆj⋅N+Pˆk⋅N)dS=∭Q∇⋅Fdv=∭Q(Mx+Ny+Pz)dv.

We will show that

∬SPˆk⋅NdS=∭QPxdv.

We have on the top surface

Pˆk⋅ndS=Pˆk⋅((−g2)xˆi−(g2)yˆj+ˆk)=P(x,y,g2(x,y)).

On the bottom surface, we get

Pˆk⋅ndS=Pˆk⋅((g1)xˆi+(g1)yˆj−ˆk)=−P(x,y,g1(x,y)).

Putting these together we get

∬SPˆk⋅NdS=∬R[P(x,y,g2(x,y))−P(x,y,g1(x,y))]dydx.

For the triple integral, the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus tell us that

∭QPzdzdydx=∬R[P(x,y,z)]g2(x,y)g1(x,y)dydx=∬R[P(x,y,g2(x,y))−P(x,y,g1(x,y))]dydx.

◻

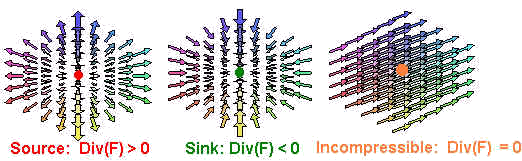

An Interpretation of Divergence

We have seen that the flux is the amount fluid flow per unit time through a surface. If the surface is closed, then the total flux will equal the flow out of the solid minus the flow in. Often in the solid there is a source (such as a star when the flow is electromagnetic radiation) or a sink (such as the earth collecting solar radiation). If we have a small solid S(P) containing a point P, then the divergence of the vector field is approximately constant, which leads to the approximation

∭Q∇⋅Fdv≈∇⋅F(P)Volume.

The divergence theorem expresses the approximation

Flux through S(P)≈∇⋅F(P)(Volume).

Dividing by the volume, we get that the divergence of F at P is the Flux per unit volume.

- If the divergence is positive, then the P is a source.

- If the divergence is negative, then P is a sink.

Contributors and Attributions

- Larry Green (Lake Tahoe Community College)

Integrated by Justin Marshall.