2.2: Multiplying Fractions

- Page ID

- 137904

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

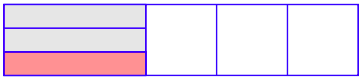

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Consider the image in Figure 4.5, where the vertical lines divide the rectangular region into three equal pieces. If we shade one of the three equal pieces, the shaded area represents 1/3 of the whole rectangular region.

We’d like to visualize taking 1/2 of 1/3. To do that, we draw an additional horizontal line which divides the shaded region in half horizontally. This is shown in Figure 4.6. The shaded region that represented 1/3 is now divided into two smaller rectangular regions, one of which is shaded with a different color. This region represents 1/2 of 1/3.

Next, extend the horizontal line the full width of the rectangular region, as shown in Figure 4.7.

Note that drawing the horizontal line, coupled with the three original vertical lines, has succeeded in dividing the full rectangular region into six smaller but equal pieces, only one of which (the one representing 1/2 of 1/3) is shaded in a new color. Hence, this newly shaded piece represents 1/6 of the whole region. The conclusion of our visual argument is the fact that 1/2 of 1/3 equals 1/6. In symbols,

\[ \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{3} = \frac{1}{6} .\nonumber \]

Example 1

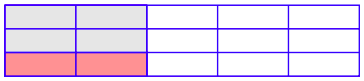

Create a visual argument showing that 1/3 of 2/5 is 2/15.

Solution

First, divide a rectangular region into five equal pieces and shade two of them. This represents the fraction 2/5.

Next, draw two horizontal lines that divide the shaded region into three equal pieces and shade 1 of the three equal pieces. This represents taking 1/3 of 2/5.

Next, extend the horizontal lines the full width of the region and return the original vertical line from the first image.

Note that the three horizontal lines, coupled with the five original vertical lines, have succeeded in dividing the whole region into 15 smaller but equal pieces, only two of which (the ones representing 1/3 of 2/5) are shaded in the new color. Hence, this newly shaded piece represents 2/15 of the whole region. The conclusion of this visual argument is the fact that 1/3 of 2/5 equals 2/15. In symbols,

\[ \frac{1}{3} \cdot \frac{2}{5} = \frac{2}{15}.\nonumber \]

Exercise

Create a visual argument showing that 1/2 of 1/4 is 1/8.

- Answer

-

Diagram:

Multiplication Rule

In Figure 4.7, we saw that 1/2 of 1/3 equals 1/6. Note what happens when we multiply the numerators and multiply the denominators of the fractions 1/2 and 1/3.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{3} = \frac{1 \cdot 1}{2 \cdot 3} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators; multiply denominators.}} \\ = \frac{1}{6} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Simplify numerators and denominators.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

We get 1/6!

Could this be coincidence or luck? Let’s try that again with the fractions from Example 1, where we saw that 1/3 of 2/5 equals 2/15. Again, multiply the numerators and denominators of 1/3 and 2/5.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{3} \cdot \frac{2}{5} = \frac{1 \cdot 2}{3 \cdot 5} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators; multiply denominators.}} \\ = \frac{2}{15} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Simplify numerators and denominators.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Again, we get 2/15!

These two examples motivate the following definition.

Definition: Multiplication Rule

To find the product of the fractions a/b and c/d, multiply their numerators and denominators. In symbols,

\[ \frac{a}{b} \cdot \frac{c}{d} = \frac{a \cdot c}{b \cdot d}\nonumber \]

Example 2

Multiply 1/5 and 7/9.

Solution

Multiply numerators and multiply denominators.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{5} \cdot \frac{7}{9} = \frac{1 \cdot 7}{5 \cdot 9} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators; multiply denominators.}} \\ = \frac{7}{45} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Simplify numerators and denominators.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Exercise

Multiply:

\[ \frac{1}{3} \cdot \frac{2}{5}\nonumber \]

- Answer

-

\( \frac{2}{15}\)

Example 3

Find the product of −2/3 and 7/9.

Solution

The usual rules of signs apply to products. Unlike signs yield a negative result.

\[ \begin{aligned} - \frac{2}{3} \cdot \frac{7}{9} = - \frac{2 \cdot 7}{3 \cdot 9} & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators; multiply denominators.}} \\ = - \frac{14}{27} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Simplify numerators and denominators.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

It is not required that you physically show the middle step. If you want to do that mentally, then you can simply write

\[ - \frac{2}{3} \cdot \frac{7}{9} = - \frac{14}{27}.\nonumber \]

Exercise

Multiply:

\[ - \frac{3}{5} \cdot \frac{2}{7}\nonumber \]

- Answer

-

\[ - \frac{6}{35}\nonumber \]

Multiply and Reduce

After multiplying two fractions, make sure your answer is reduced to lowest terms (see Section 4.1).

Example 4

Multiply 3/4 times 8/9.

Solution

After multiplying, divide numerator and denominator by the greatest common divisor of the numerator and denominator.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{8}{9} = \frac{3 \cdot 8}{4 \cdot 9} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators and denominators.}} \\ = \frac{24}{36} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Simplify numerator and denominator.}} \\ = \frac{24 \div 12}{36 \div 12} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Divide numerator and denominator by GCD.}} \\ = \frac{2}{3} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Simplify numerator and denominator.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Alternatively, after multiplying, you can prime factor both numerator and denominator, then cancel common factors.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{8}{9} = \frac{24}{36} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators and denominators.}} \\ = \frac{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdot 3} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Prime factor numerator and denominator.}} \\ = = \frac{\cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{2} \cdot 2 \cdot \cancel{3}}{\cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{2} \cdot 3 \cdot \cancel{3}} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Cancel common factors.}} \\ = \frac{2}{3} ~ \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Exercise

Multiply:

\[ \frac{3}{7} \cdot \frac{14}{9}\nonumber \]

- Answer

-

\[ \frac{2}{3}\nonumber \]

Multiply and Cancel or Cancel and Multiply

When you are working with larger numbers, it becomes a bit harder to multiply, factor, and cancel. Consider the following argument.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{18}{30} \cdot \frac{35}{6} = \frac{630}{180} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators; multiply denominators.}} \\ = \frac{2 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7}{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 5} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Prime factor numerators and denominators.}} \\ = \frac{ \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{5} \cdot 7}{2 \cdot \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{5}} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Cancel common factors.}} \\ = \frac{7}{2} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Remaining factors.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

There are a number of difficulties with this approach. First, you have to multiply large numbers, and secondly, you have to prime factor the even larger results.

One possible workaround is to not bother multiplying numerators and denominators, leaving them in factored form.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{18}{30} \cdot \frac{35}{6} = \frac{18 \cdot 35}{30 \cdot 6} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators; multiply denominators.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Finding the prime factorization of these smaller factors is easier.

\[ \begin{aligned} = \frac{(2 \cdot 3 \cdot 3) \cdot (5 \cdot 7)}{(2 \cdot 3 \cdot 5) \cdot (2 \cdot 3)} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Prime factor.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Now we can cancel common factors. Parentheses are no longer needed in the numerator and denominator because both contain a product of prime factors, so order and grouping do not matter.

\[ \begin{aligned} = \frac{ \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{5} \cdot \cancel{7}}{ \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{5} \cdot 2 \cdot \cancel{3}} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Cancel common factors.}} \\ = \frac{7}{2} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Remaining factors.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Another approach is to factor numerators and denominators in place, cancel common factors, then multiply.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{18}{30} \cdot \frac{35}{6} = \frac{2 \cdot 3 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 3 \cdot 5} \cdot \frac{5 \cdot 7}{2 \cdot 3} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Factor numerators and denominators.}} \\ = \frac{ \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{3}}{ \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{5}} \cdot \frac{ \cancel{5} \cdot 7}{2 \cdot \cancel{3}} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Cancel common factors.}} \\ = \frac{7}{2} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Remaining factors.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Note that this yields exactly the same result, 7/2.

Cancellation Rule

When multiplying fractions, cancel common factors according to the following rule: “Cancel a factor in a numerator for an identical factor in a denominator.”

Example 6

Find the product of 14/15 and 30/140.

Solution

Multiply numerators and multiply denominators. Prime factor, cancel common factors, then multiply.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{14}{15} \cdot \frac{30}{140} = \frac{14 \cdot 30}{15 \cdot 140} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators; multiply denominators.}} \\ = \frac{(2 \cdot 7) \cdot (2 \cdot 3 \cdot 5)}{(3 \cdot 5) \cdot (2 \cdot 2 \cdot 5 \cdot 7)} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Prime factor numerators and denominators.}} \\ = \frac{ \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{7} \cdot \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{3} \cdot \cancel{5}}{ \cancel{3} \cdot 5 \cdot \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{2} \cdot \cancel{5} \cdot \cancel{7}} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Cancel common factors.}} \\ = \frac{1}{5} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Note: Everything in the numerator cancels because you’ve divided the numerator by itself. Hence, the answer has a 1 in its numerator.

Exercise

Multiply:

\[ \frac{6}{35} \cdot \frac{70}{36}\nonumber \]

- Answer

-

\(\frac{1}{3}\)

When Everything Cancels

When all the factors in the numerator cancel, this means that you are dividing the numerator by itself. Hence, you are left with a 1 in the numerator. The same rule applies to the denominator. If everything in the denominator cancels, you’re left with a 1 in the denominator.

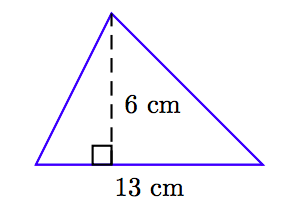

Area of a Triangle

A triangle having base b and height h has area A = (1/2)bh. That is, to find the area of a triangle, take one-half the product of the base and height.

Example 9

Find the area of the triangle pictured below.

Solution

To find the area of the triangle, take one-half the product of the base and height.

\[ \begin{aligned} A = \frac{1}{2} bh ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Area of a triangle formula.}} \\ = \frac{1}{2} (13 \text{ cm}) (6 \text{ cm}) ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Substitute: 13 cm for } b,~ \text{6 cm for } h.} \\ = \frac{78 \text{ cm}^2}{2} ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Multiply numerators; multiply denominators.}} \\ = 39 \text{ cm}^2. ~ & \textcolor{red}{ \text{ Simplify.}} \end{aligned}\nonumber \]

Therefore, the area of the triangle is 39 square centimeters.

Exercise

The base of a triangle measures 15 meters. The height is 12 meters. What is the area of the triangle?

- Answer

-

90 square meters

Exercises

Multiply the fractions and simplify your result.

1. \(\frac{21}{4} \cdot \frac{2}{7}\)

2. \(\frac{−9}{2} \cdot \frac{6}{7}\)

3. \(\frac{2}{15} \cdot \frac{-9}{8}\)

4. \(\frac{-21}{20} \cdot \frac{−20}{21}\)

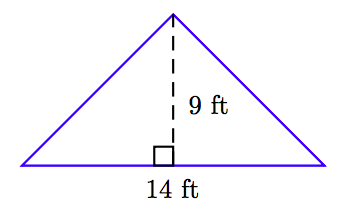

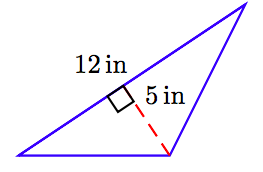

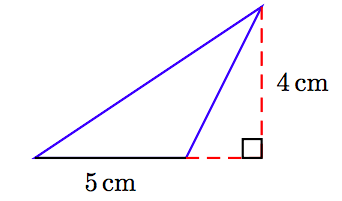

Find the area of the triangle shown in the figure. (Note: Figures are not drawn to scale.)

5.

6.

7.

8. Weight on the Moon. On the moon, you would only weigh 1/6 of what you weigh on earth. If you weigh 138 pounds on earth, what would your weight on the moon be?

Answers

1. \(\frac{3}{2}\)

2. \(\frac{−27}{7}\)

3. \(\frac{−3}{20}\)

4. 1

5. 63 ft2

6. 30 in2

7. 10 cm2

8. 23 pounds