5.5: Volumes: Tubes

- Page ID

- 212048

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In Section 5.2, we devised the “disk” method to find the volume swept out when a region is revolved about a line. To find the volume swept out when revolving a region about the \(x\)-axis:

we made cuts perpendicular to the \(x\)-axis so that each slice was (approximately) a “disk” with volume \(\pi\left(\mbox{radius}\right)^2\cdot\left(\mbox{thickness}\right)\). Adding the volumes of these slices together yielded a Riemann sum. Taking a limit as the thicknesses of the slices approached \(0\), we obtained a definite integral representation for the exact volume that had the form:\[\int_a^b \pi \left[f(x)\right]^2 \, dx\nonumber\nonumber\]The disk method, while useful in many circumstances, can be cumbersome if we want to find the volume when a region defined by a curve of the form \(y=f(x)\) is revolved about the \(y\)-axis or some other vertical line. To revolve the region about the \(y\)-axis, the disk method requires that we rewrite the original equation \(y = f(x)\) as \(x = g(y)\). Sometimes this is easy: if \(y = 3x\) then \(x = \frac{y}{3}\). But sometimes it is not easy at all: if \(y = x + e^x\), then we cannot solve for \(x\) as an elementary function of \(y\). (Refer to Examples 6(b) and 6(c) from Section 5.2 to refresh your memory.)

The “Tube” Method

Partition the \(x\)-axis (as we did in the “disk” method) to cut the region into thin, almost-rectangular vertical “slices.” When we revolve one of these slices about the \(y\)-axis (see below), we can approximate the volume of the resulting “tube” by cutting the “wall” of the tube and rolling it out flat:

to get a thin, solid rectangular box. The volume of the tube is approximately the same as the volume of the solid box: \begin{align*} V_{\mbox{tube}} \approx V_{\mbox{box}} &= \left(\mbox{length}\right)\cdot\left(\mbox{height}\right)\cdot\left(\mbox{thickness}\right) \\ &= \left(2\pi\cdot \left[\mbox{radius}\right]\right)\cdot\left(\mbox{height}\right)\cdot\left(\Delta x_k\right)\\ &= \left(2\pi c_k\right)\Big(f\left(c_k\right)\Big)\cdot \Delta x_k \end{align*} where \(c_k\) is (as usual) any point chosen from the interval \(\left[x_{k-1}, x_k\right]\).

The volume swept out when we revolve the whole region about the \(y\)-axis is (approximately) the sum of the volumes of these “tubes,” which is a Riemann sum that converges to a definite integral:\[\sum_{k=1}^n \, \left(2\pi c_k\right)\Big(f\left(c_k\right)\Big)\cdot \Delta x_k \ \longrightarrow \ \int_a^b 2\pi x \cdot f(x) \ dx\nonumber\nonumber\]

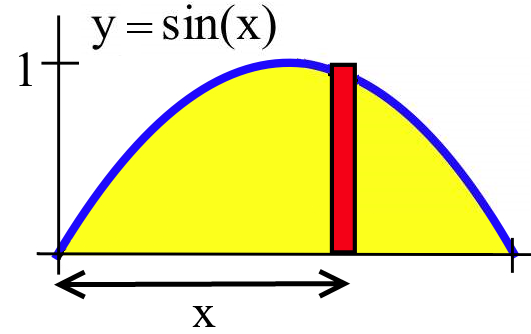

Use a definite integral to represent the volume of the solid generated by rotating the region between the graph of \(y = \sin(x)\) (for \(0 \leq x \leq \pi\)) and the \(x\)-axis around the \(y\)-axis.

Solution

Slicing this region vertically yields slices with width \(\Delta x\) and height \(\sin(x)\):

Rotating a slice located \(x\) units away from the \(y\)-axis results in a “tube” with volume:\[2\pi \left(\mbox{radius}\right)\left(\mbox{height}\right)\left(\mbox{thickness}\right) = 2\pi\left(x\right)\Big(\sin(x)\Big)\Delta x\nonumber\nonumber\]where the radius of the tube (\(x\)) is the distance from the slice to the \(y\)-axis and the height of the tube is the height of the slice (\(\sin(x)\)). Adding the volumes of all such tubes yields a Riemann sum that converges to a definite integral:\[\int_0^{\pi} 2\pi \left(\mbox{radius}\right)\left(\mbox{height}\right) \, dx = \int_0^{\pi} 2\pi x \sin(x) \, dx\nonumber\nonumber\]We don’t (yet) know how to find an antiderivative for \(x\sin(x)\) but we can use technology (or a numerical method from Section 4.9) to compute the value of the integral, which turns out to be \(2\pi^2 \approx 19.74\). (You’ll learn how to find an antiderivative for \(x\sin(x)\) in Section 8.2 or, for now, you can look for this pattern in Appendix I.)

Use a definite integral to compute the volume of the solid generated by rotating the region in the first quadrant bounded by \(y = 4x-x^2\) about the \(y\)-axis.

- Answer

-

Graph the region:

and note that the curve \(y=4x-x^2\) intersects the \(x\)-axis where \(4x-x^2=0 \Rightarrow x(4-x)=0 \Rightarrow x = 0\) or \(x=4\). Rotating a vertical slice around the \(y\)-axis results in a tube with radius \(x\) (the distance between the slice and the \(y\)-axis) and height \(4x-x^2\) so the volume of the solid is:

\begin{align*}\int_0^4 2\pi x\left(4x-x^2\right)\, dx &= 2\pi\int_0^4\left[4x^2-x^3\right]\, dx \\

&= 2\pi\left[\frac43 x^3 -\frac14 x^4\right]_0^4 = \frac{128\pi}{3} \approx 134\end{align*}

If we had sliced the region in Example 1 horizontally instead of vertically, the rotated slices would have resulted in “washers”; applying the “washer” method from Section 5.2 yields the integral:\[\int_0^1 \pi\left[\left(\pi-\arcsin(y)\right)^2 - \left(\arcsin(y)\right)^2\right] \, dy\nonumber\nonumber\]The value of this integral is also \(2\pi^2\), but finding an antiderivative for this integrand will be much more challenging than finding an antiderivative for \(x\sin(x)\). (Furthermore, the washer-method integral in this situation is more challenging to set up than the integral using the tube method, so the tube method is the most efficient choice on all counts.)

Rotating About Other Axes

The “tube” method extends easily to solids generated by rotating a region about any vertical line (not just the \(y\)-axis).

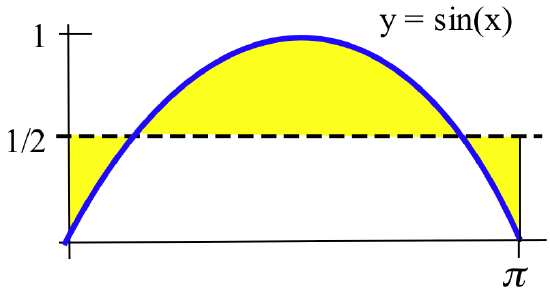

Use a definite integral to represent the volume of the solid generated by rotating the region between the graph of \(y = \sin(x)\) (for \(0 \leq x \leq \pi\)) and the \(x\)-axis around the line \(x = 4\).

Solution

The region is the same as the one in Example 1, but here we're rotating that region about a different vertical line:

Vertical slices again generate tubes when rotated about \(x=4\); the only difference here is that the radius for a slice located \(x\) units away from \(y\)-axis is now \(4-x\) (the distance from the axis of rotation to the slice). The volume integral becomes:\[\int_0^{\pi} 2\pi \left(\mbox{radius}\right)\left(\mbox{height}\right) \, dx = \int_0^{\pi} 2\pi (4-x) \cdot \sin(x) \, dx\nonumber\nonumber\]which turns out to be \(2\pi(8-\pi) \approx 4.8584\). (Use technology — or a table of integrals — to verify this numerical result.)

Use a definite integral to compute the volume of the solid generated by rotating the region in the first quadrant bounded by \(y = 4x-x^2\) about the line \(x = -7\).

- Answer

-

The region here is identical to the region in Practice 1, but we are now rotating a slice around the axis \(x=-7\), so the radius of the resulting tube is \(x-(-7) = x+7\) (the distance from the slice at location \(x\) to the axis of rotation). The volume of the solid is therefore:

\begin{align*}\int_0^4 2\pi (x+7)\left(4x-x^2\right)\, dx &= 2\pi\int_0^4\left[28x-3x^2-x^3\right]\, dx \\

&= 2\pi\left[14x^2 - x^3 -\frac14 x^4\right]_0^4 = 192\pi \approx 603\end{align*}

More General Regions

The “tube” method also extends easily to more general regions. (Many textbooks refer to this method as the “method of cylindrical shells” or the “shell method,” but “cylindrical shells” is a mouthful compared with “tube,” and “shell method” is not precise, as shells are not necessarily cylindrical.)

If: the region constrained by the graphs of \(y = f(x)\) and \(y = g(x)\) and the interval \([a, b]\) is revolved about a vertical line \(x = c\) that does not intersect the region

then: the volume of the resulting solid is:\[V = \int_a^b 2\pi \cdot \left|x-c\right|\cdot \left|f(x)-g(x)\right|\, dx\nonumber\nonumber\]

The absolute values appear in the general formula because the radius and the height are both distances, hence both must be positive. You can ensure that these ingredients in your tube-method integral will be positive by always subtracting smaller values from larger values: think “\(\mbox{right}-\mbox{left}\)” for \(x\)-values and “\(\mbox{top}-\mbox{bottom}\)” for \(y\)-values.

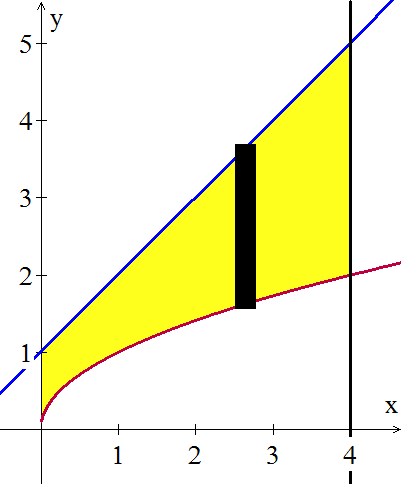

Compute the volume of the solid generated by rotating the region between the graphs of \(y = x\) and \(y = x^2\) for \(2 \leq x \leq 4\) around the \(y\)-axis using:

- vertical slices and

- horizontal slices.

Solution

- Vertical slices result in tubes when rotated about the \(y\)-axis:

![A red graph of y=x^2 and a blue graph of y=x are shown on a [0,4]X[0,15] grid with dashed-black vertical line segments extending up form the x-axis to through the red curve at x=2 and x=4. The region between the curves and the dashed lines is shaded yellow. Midway between the dashed lines, a thin black rectangle extends up from the blue line to the red curve.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/140845/fig505_5.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=303&height=268)

and a slice \(x\) units away from the \(y\)-axis results in a tube of radius \(x\) and height \(x^2-x\), so the volume of the solid is: \begin{align*} \int_2^4 2\pi x \left[x^2-x\right]\, dx &= 2\pi \int_2^4 \left[x^3-x^2\right]\, dx = 2\pi\left[\frac14 x^4 - \frac13 x^3\right]_2^4\\ &= 2\pi\left[\left(64-\frac{64}{3}\right)-\left(4-\frac83\right)\right] = \frac{248\pi}{3}\end{align*} or about \(259.7\). - Horizontal slices result in washers when rotated about the \(y\)-axis, but we have a new problem: the lower slices (where \(2 \leq y \leq 4\)) extend from the line \(x=2\) on the left to the line \(y=x\) on the right, while the upper slices (where \(4 \leq y \leq 16\)) extend from the parabola \(y=x^2\) on the left to the line \(x=4\) on the right.

![A red graph of y=x^2 and a blue graph of y=x are shown on a [0,4]X[0,15] grid with dashed-black vertical line segments extending up form the x-axis to through the red curve at x=2 and x=4. The region between the curves and the dashed lines is shaded yellow. A thin black rectangle extends from the left dashed line near (2,3) rightward to the blue line. Another such black rectangle extends from the red curve near (2.8,7.84) rightward to the right dashed line.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/140851/fig505_6.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=303&height=268)

This requires us to use two integrals to compute the volume:\[\int_{y=2}^{y=4} \pi\left[y^2-2^2\right]\, dy + \int_{y=4}^{y=16} \pi\left[4^2-\left(\sqrt{y}\right)^2\right]\, dy\nonumber\nonumber\]Evaluating these integrals also results in a volume of \(\frac{248\pi}{3} \approx 259.7\). (Evaluating these integrals is straightforward, but setting them up was more time-consuming than using the tube method.)

Find the volume of the solid formed by rotating the region between the graphs of \(y = x\) and \(y = x^2\) for \(2 \leq x \leq 4\) around \(x = 13\).

- Answer

-

Rotating a vertical slice about the line \(x=13\) results in a tube with radius \(13-x\) and height \(x^2-x\):

![A red graph of y=x^2 and a blue graph of y=x are shown on a [0,4]X[0,15] grid with dashed-black vertical line segments extending up form the x-axis to through the red curve at x=2 and x=4. The region between the curves and the dashed lines is shaded yellow. A thin black rectangle extends from the left dashed line near (2,3) rightward to the blue line. Another such black rectangle extends from the red curve near (2.8,7.84) rightward to the right dashed line.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/140851/fig505_6.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=303&height=268)

so the volume of the solid is:

\begin{align*}\int_2^4 & 2\pi(13-x)(x^2-x)\, dx = 2\pi\int_2^4 \left[-13x+14x^2-x^3\right]\, dx \\

&= 2\pi \left[-\frac{13}{2}x^2+\frac{14}{3}x^3-\frac14 x^4\right]_2^4 = 2\pi\left[\frac{392}{3}-\frac{10}{3}\right] = \frac{764\pi}{3} \approx 800\end{align*}

Compute the volume of the solid generated by rotating the region in the first quadrant bounded by the graphs of \(y = \sqrt{x}\), \(y = x+1\) and \(x = 4\) around:

- the \(y\)-axis

- the \(x\)-axis.

- Answer

-

Graph the region and draw a representative vertical slice:

(Horizontal slices would require splitting the region into two pieces — why?)

- Rotating the vertical slice about the \(y\)-axis results in a tube of radius \(x\) (the distance from the slice to the \(y\)-axis) and height \((x+1)-\sqrt{x}\), and the region sits between \(x=0\) and \(x=4\) so the volume of the solid is: \begin{align*}\int_0^4 2\pi x \left[x+1-x^{\frac12}\right]\, dx &= 2\pi \int_0^4 \left[x^2+x-x^{\frac32}\right]\, dx \\ &= 2\pi\left[\frac13 x^3 +\frac12 x^2 - \frac25 x^{\frac52}\right]_0^4 = \frac{496\pi}{15} \approx 104\end{align*}

- Rotating the vertical slice around the \(x\)-axis results in a washer with big radius \(x+1\) (the distance from the \(x\)-axis to the curve farthest from the \(x\)-axis) and small radius \(\sqrt{x}\) (the distance from the \(x\)-axis to the closer curve) so the volume of the solid is:\[\int_0^4 \pi\left[\left(x+1\right)^2-\left(\sqrt{x}\right)^2\right]\, dx = \pi \int_0^4 \left[x^2+x+1\right]\, dx = %\pi\left[\frac13 x^3 +\frac12 x^2 +x\right]_0^4 = \frac{100\pi}{3} \approx 105\nonumber\nonumber\]

Compute the volume of the solid swept out by rotating the region in the first quadrant between the graphs of \(\displaystyle y = \sqrt{\frac{x}{2}}\) and \(y = \sqrt{x-1}\) about the \(x\)-axis.

Solution

Graphing the region:

![The region between a blue graph of y=sqrt(x/2) and a red graph of y=sqrt(x-1) on the grid [0,2]X[0,1] is shaded shaded yellow. A thin black rectangle extends up from the x-axis to the blue curve near x=0.4 and another such rectangle extends up from the red curve to the blue curve near x=1.3.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/140844/fig505_7.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=313&height=188)

it is apparent that the curves intersect where:\[\sqrt{\frac{x}{2}} = \sqrt{x-1} \ \Rightarrow \ \frac{x}{2} = x-1 \ \Rightarrow \ x = 2\nonumber\nonumber\]Slicing the region vertically results in two cases: when \(0\leq x \leq 1\), the slice extends from the \(x\)-axis to the curve \(y = \sqrt{\frac{x}{2}}\); when \(1 \leq x \leq 2\), the slice extends from \(y = \sqrt{x-1}\) to \(y = \sqrt{\frac{x}{2}}\). Rotating the first type of slice about the \(x\)-axis results in a disk; rotating the second type of slice about the \(x\)-axis results in a washer. Using the disk method for the first interval and the washer method for the second interval, the volume of the solid is:\[\int_0^1 \pi\left[\sqrt{\frac{x}{2}}\right]^2 \ dx \ + \ \int_1^2 \pi\left[\left(\sqrt{\frac{x}{2}}\right)^2-\left(\sqrt{x-1}\right)^2\right]\, dx\nonumber\nonumber\](Both types of slices are perpendicular to the \(x\)-axis, so the width of each slice is of the form \(\Delta x\) and our integrals should involve \(dx\).) Evaluating these integrals is straightforward:\[\pi \int_0^1 \frac{x}{2} \, dx + \pi \int_1^2 \left[\frac{x}{2}-\left(x-1\right)\right]\, dx =\pi\left[\frac{x^2}{4}\right]_0^1 + \pi\left[x-\frac{x^2}{4}\right]_1^2 = \frac{\pi}{2}\nonumber\nonumber\]If you had instead sliced the region horizontally, you would only need one type of slice:

![The region between a blue graph of y=sqrt(x/2) and a red graph of y=sqrt(x-1) on the grid [0,2]X[0,1] is shaded shaded yellow. A thin black horizontal rectangle extends rightward from the blue curve near (0.32,0.4) to the red curve.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/140847/fig505_8.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=313&height=188)

Rotating a horizontal slice around the \(x\)-axis results in a tube. Because this slice is perpendicular to the \(y\)-axis, the thickness of the slice is of the form \(\Delta y\), so the tube-method integral will include a \(dy\) and we will need to formulate the radius and “height” of the tube in terms of \(y\). The radius of the slice is merely \(y\), the distance between the slice and the \(x\)-axis. The “height” of the slice is its length, which is the distance between the two curves. The left-hand curve is:\[y = \sqrt{\frac{x}{2}} \ \Rightarrow \ y^2 = \frac{x}{2} \ \Rightarrow x = 2y^2\nonumber\nonumber\]and the right-hand curve is:\[y = \sqrt{x-1} \ \Rightarrow \ y^2 = x -1 \ \Rightarrow \ x = y^2 + 1\nonumber\nonumber\]so the distance between the two curves is:\[\left(y^2+1\right)-\left(2y^2\right) = 1-y^2\nonumber\nonumber\]The curves intersect where: \(y^2+1 = 2y^2 \Rightarrow y^2 = 1 \Rightarrow y = \pm 1\); from the graph we can see that the bottom of the region corresponds to \(y = 0\) and the top of the region is at \(y=1\). Applying the tube method, the volume of the solid is:\[\int_{y=0}^{y=1} 2\pi y \cdot \left[1-y^2\right]\, dy = 2\pi \int_0^1 \left[y-y^3\right]\, dy = 2\pi\left[\frac{y}{2} - \frac{y^4}{4}\right]_0^1 = \frac{\pi}{2}\nonumber\nonumber\]which agrees with the result above from the disk\(+\)washer method.

(This application of the tube method rotates a horizontal slice around a horizontal axis; in previous tube-method applications we have only rotated a vertical slice about a vertical axis. Either option results in a tube, and the general formula on page 433 can be further extended to this new situation — as we have done here — by swapping the roles of \(x\) and \(y\).)

Compute the volume of the solid swept out by rotating the region in the first quadrant between the graphs of \(\displaystyle y = \sqrt{\frac{x}{2}}\) and \(y = \sqrt{x-1}\) about:

- the line \(x = 5\)

- the line \(y=5\).

- Answer

-

This region is the same as the one in Example 4, where it was apparent that slicing horizontally resulted in a single type of slice (compared with vertical slices, which required us to split the region into two pieces):

![The region between a blue graph of y=sqrt(x/2) and a red graph of y=sqrt(x-1) on the grid [0,2]X[0,1] is shaded shaded yellow. A thin black horizontal rectangle extends rightward from the blue curve near (0.32,0.4) to the red curve.](https://math.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/140847/fig505_8.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=313&height=188)

- Rotating a horizontal slice around the vertical line \(x=5\) results in washers with thickness \(\Delta y\) (so our integral will involve \(dy\)), big radius \(5-2y^2\) (the distance between the axis of rotation and the farthest curve) and small radius \(5-\left(y^2+1\right) = 4-y^2\) (the distance between the axis of rotation and closest curve). Applying the washer method, the volume of the solid is:\[\int_0^1 \pi\left[\left(5-2y^2\right)^2-\left(4-y^2\right)^2\right]\, dy = \frac{14\pi}{5} \approx 8.8\nonumber\nonumber\]

- Rotating a horizontal slice around the horizontal line \(y=5\) results in a tube of radius \(5-y\) (the distance between the slice and the axis of rotation) and “height” \(1-y^2\) (the length of the slice). Applying the tube method, the volume of the solid is:\[\int_0^1 2\pi(5-y)\left(1-y^2\right)\, dy = \frac{37\pi}{6} \approx 19.4\nonumber\nonumber\]

Which Method Is Best?

In theory, both the washer method and the tube method will work for any volume-of-revolution problem involving a horizontal or vertical axis. (We will investigate a method for computing volumes of solids formed by rotating a region around “tilted” axes in Section 5.6.)

In practice, however, one of these methods is usually easier to use than the other — but which one is easier depends on the particular region and type of axis. As we have seen, challenges may include:

- The necessity to split the region into two (or more) pieces, resulting in two (or more) integrals.

- The difficulty (or impossibility) of solving an equation of the form \(y = f(x)\) for \(x\) or an equation of the form \(x = g(y)\) for \(y\).

- The difficulty (or impossibility) of finding an antiderivative for the resulting integrand.

With experience (and lots of practice) you will begin to develop an intuition for which method might be the best choice for a particular situation. Sketching the region along with representative horizontal and vertical slices is a vital first step.

The method that avoids the need to split the region up into more than one piece is often — but not always — the superior choice. Avoiding the need to find an inverse function for a boundary curve should also be a priority. Finally, if you need an exact value and one method results in a challenging antiderivative search, start over and try the other method.

Problems

In Problems 1–6, sketch the region and calculate the volume swept out when the region is revolved about the specified vertical line.

- The region in the first quadrant between the curve \(\displaystyle y = \sqrt{1 - x^2}\) and the \(x\)-axis is rotated about the \(y\)-axis.

- The region in the first quadrant between the curve \(y = 2x - x^2\) and the \(x\)-axis is rotated about the \(y\)-axis.

- The region in the first quadrant between between \(y = 2x\) and \(y = x^2\) for \(0 \leq x \leq 3\) is rotated about the line \(x = 4\).

- The region in the first quadrant between the curve \(\displaystyle y = \frac{1}{1 + x^2}\), the \(x\)-axis and the line \(x=3\) is rotated about the \(y\)-axis.

- The region between \(\displaystyle y = \frac{1}{x}\), \(\displaystyle y = \frac13\) and \(x = 1\) is rotated about the line \(x = 5\).

- The region between \(y = x\), \(y = 2x\), \(x = 1\) and \(x = 3\) is rotated about the line \(x = 1\).

In Problems 7–11, use a definite integral to represent the volume swept out when the given region is revolved about the \(y\)-axis, then use technology to evaluate the integral.

- The region in the first quadrant between the graphs of \(y = \ln(x)\), \(y = x\) and \(x = 4\).

- The region in the first quadrant between the graphs of \(y = e^x\), \(y = x\) and \(x = 2\).

- The region between \(y = x^2\) and \(y = 6 - x\) for \(1 \leq x \leq 4\).

- The shaded region in the figure below:

- The shaded region in the figure below:

In Problems 12–30, set up an integral to calculate the volume swept out when the region between the given curves is rotated about the specified axis, using any appropriate method (disks, washers, tubes). If possible, work out an exact value of the integral; otherwise, use technology to find an approximate numerical value.

- \(y=x\), \(y=x^4\), about the \(y\)-axis

- \(y=x^2\), \(y=x^4\), about the \(y\)-axis

- \(y=x^2\), \(y=x^4\), about the \(x\)-axis

- \(y=\sin(x^2)\), \(y=0\), \(x=0\), \(x=\sqrt{\pi}\), about \(x=0\)

- \(y=\cos(x^2)\), \(y=0\), \(x=0\), \(x=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\), about \(x=0\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\), \(y=0\), \(x=0\), \(x=\frac12\), about \(x=0\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\), \(y=0\), \(x=0\), \(x=\frac12\), about \(y=0\)

- \(y=x\), \(y=x^4\), about \(x=3\)

- \(y=x\), \(y=x^4\), about \(y=3\)

- \(y=x\), \(y=x^4\), about \(y=-3\)

- \(y=x\), \(y=x^4\), about \(x=-3\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\frac{1}{1+x^2}\), \(y=0\), \(x=0\), \(x=1\) about \(x=2\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\frac{1}{1+x^2}\), \(y=0\), \(x=1\), \(x=\sqrt{3}\), about \(x=2\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\frac{1}{1+x^2}\), \(y=1\), \(x=1\), about \(x=-2\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\frac{1}{1+x^2}\), \(y=\frac12\), about \(x=1\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\sqrt{x-2}\), \(y=\sqrt{x-1}\), \(y=0\), \(x=3\), about \(x=4\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\sqrt{x-2}\), \(y=\sqrt{x-1}\), \(y=0\), \(x=3\), about \(x=-4\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\sqrt{x-2}\), \(y=\sqrt{x-1}\), \(y=0\), \(x=3\), about \(y=4\)

- \(\displaystyle y=\sqrt{x-2}\), \(y=\sqrt{x-1}\), \(y=0\), \(x=3\), about \(y=-4\)