0.3: Radicals and Rational Expressions

- Page ID

- 193543

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Evaluate square roots.

- Use the product rule to simplify square roots.

- Use the quotient rule to simplify square roots.

- Add and subtract square roots.

- Use rational roots.

A hardware store sells \(16\)-ft ladders and \(24\)-ft ladders. A window is located \(12\) feet above the ground. A ladder needs to be purchased that will reach the window from a point on the ground \(5\) feet from the building. To find out the length of ladder needed, we can draw a right triangle as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), and use the Pythagorean Theorem.

\[\begin{align*} a^2+b^2=c^2 \\[4pt] 5^2+12^2=c^2 \\[4pt] 169=c^2 \end{align*}\]

As you see, we are left with \(169\) is equal to the length of the ladder squared. How do we get the exponent away from the variable? To do this, we will take the square root of each side. In this section, we investigate the methods of finding solutions to problems such as this one.

Evaluating Square Roots

A square root tells you what number was multiplied by itself to get a certain number. For example, the square root of \(9\) is \(3\), because \(3 \cdot 3 = 9\). Since \(4^2=16\), then the square root of \(16\) equals \(16\). The square root is the inverse of the squaring function, just as subtraction is the inverse of addition. To undo squaring, we take the square root.

When taking the square root of a number, we actually get two results: a positive and a negative. For example, earlier we stated that the square root of \(9\) is \(3\), because \(3 \cdot 3 = 9\). But the square root of \(9 \) is also \(-3\) as \((-3) \cdot (-3) = 9\). Since we have two values, we will refer to the positive value as the principal square root. When using a calculator, it will always return the principal square root.

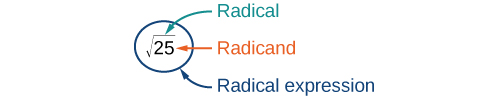

The principal square root of \(a\) is written as \(\sqrt{a}\). The symbol is called a radical, the term under the symbol is called the radicand, and the entire expression is called a radical expression.

Does \(\sqrt{25} = \pm 5\)?

Solution

No. Although both \(5^2\) and \((−5)^2\) are \(25\), the radical symbol implies only a nonnegative root, the principal square root. The principal square root of \(25\) is \(\sqrt{25}=5\).

The principal square root of \(a\) is the nonnegative number that, when multiplied by itself, equals \(a\). It is written as a radical expression, with a symbol called a radical over the term called the radicand: \(\sqrt{a}\).

Evaluate each expression.

- \(\sqrt{\sqrt{16}}\)

- \(\sqrt{49}\)-\(\sqrt{81}\)

Solution

- \(\sqrt{\sqrt{16}}= \sqrt{4} =2\) because \(4^2=16\) and \(2^2=4\)

- \(\sqrt{49} -\sqrt{81} =7−9 =−2\) because \(7^2=49\) and \(9^2=81\)

For \(\sqrt{25+144}\),can we find the square roots before adding?

Solution

No. \(\sqrt{25} + \sqrt{144} =5+12=17\). This is not equivalent to \(\sqrt{25+144}=13\). The order of operations requires us to add the terms in the radicand before finding the square root.

Evaluate each expression.

- \(\sqrt{\sqrt{81}}\)

- \(\sqrt{36} + \sqrt{121}\)

- Answer a

-

\(3\)

- Answer b

-

\(17\)

Using the Product Rule to Simplify Square Roots

To simplify a square root, we rewrite it such that there are no perfect squares in the radicand. There are several properties of square roots that allow us to simplify complicated radical expressions. The first rule we will look at is the product rule for simplifying square roots, which allows us to separate the square root of a product of two numbers into the product of two separate rational expressions. For instance, we can rewrite \(\sqrt{15}\) as \(\sqrt{3}\times\sqrt{5}\). We can also use the product rule to express the product of multiple radical expressions as a single radical expression.

If \(a\) and \(b\) are nonnegative, the square root of the product \(ab\) is equal to the product of the square roots of \(a\) and \(b\)

\[\sqrt{ab}=\sqrt{a}\times\sqrt{b}\]

- Factor any perfect squares from the radicand.

- Write the radical expression as a product of radical expressions.

- Simplify.

Simplify the radical expression.

- \(\sqrt{300}\)

- \(\sqrt{162a^5b^4}\)

Solution

a. \(\sqrt{100\times3}\) Factor perfect square from radicand.

\(\sqrt{100}\times\sqrt{3}\) Write radical expression as product of radical expressions.

\(10\sqrt{3}\) Simplify

b. \(\sqrt{81a^4b^4\times2a}\) Factor perfect square from radicand

\(\sqrt{81a^4b^4}\times\sqrt{2a}\) Write radical expression as product of radical expressions

\(9a^2b^2\sqrt{2a}\) Simplify

- Express the product of multiple radical expressions as a single radical expression.

- Simplify.

Simplify the radical expression.

\(\sqrt{12}\times\sqrt{3}\)

Solution

\[\begin{align*} &\sqrt{12\times3}\qquad \text{Express the product as a single radical expression}\\ &\sqrt{36}\qquad \text{Simplify}\\ &6 \end{align*}\]

- Simplify \(\sqrt{50x}\times\sqrt{2x}\) assuming \(x>0\).

- Simplify \(\sqrt{50x^2y^3z}\)

- Answer a

-

\(10|x|\)

- Answer b

-

\(5|x||y|\sqrt{2yz}\)

Notice the absolute value signs around \(x\) and \(y\)? That’s because their value must be positive!

Using the Quotient Rule to Simplify Square Roots

Just as we can rewrite the square root of a product as a product of square roots, so too can we rewrite the square root of a quotient as a quotient of square roots, using the quotient rule for simplifying square roots. It can be helpful to separate the numerator and denominator of a fraction under a radical so that we can take their square roots separately. We can rewrite

\[\sqrt{\dfrac{5}{2}} = \dfrac{\sqrt{5}}{\sqrt{2}}. \nonumber \]

The square root of the quotient \(\dfrac{a}{b}\) is equal to the quotient of the square roots of \(a\) and \(b\), where \(b≠0\).

\[\sqrt{\dfrac{a}{b}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{b}}\]

- Write the radical expression as the quotient of two radical expressions.

- Simplify the numerator and denominator.

Simplify the radical expression.

\(\sqrt{\dfrac{5}{36}}\)

Solution

\[\begin{align*} &\dfrac{\sqrt{5}}{\sqrt{36}}\qquad \text{Write as quotient of two radical expressions}\\ &\dfrac{\sqrt{5}}{6}\qquad \text {Simplify denominator} \end{align*}\]

Simplify the radical expression.

\(\dfrac{\sqrt{234x^{11}y}}{\sqrt{26x^7y}}\)

Solution

\[\begin{align*} &\sqrt{\dfrac{234x^{11}y}{26x^7y}}\qquad \text{Combine numerator and denominator into one radical expression}\\ &\sqrt{9x^4}\qquad \text{Simplify fraction}\\ &3x^2\qquad \text{Simplify square root} \end{align*}\]

- Simplify \(\sqrt{\dfrac{2x^2}{9y^4}}\)

- Simplify \(\dfrac{\sqrt{9a^5b^{14}}}{\sqrt{3a^4b^5}}\)

- Answer

-

\(\dfrac{x\sqrt{2}}{3y^2}\)

We do not need the absolute value signs for \(y^2\) because that term will always be nonnegative.

- Answer

-

\(b^4\sqrt{3ab}\)

Adding and Subtracting Square Roots

We can add or subtract radical expressions only when they have the same radicand and when they have the same radical type such as square roots. For example, the sum of \(\sqrt{2}\) and \(3\sqrt{2}\) is \(4\sqrt{2}\). However, it is often possible to simplify radical expressions, and that may change the radicand. The radical expression \(\sqrt{18}\) can be written with a \(2\) in the radicand, as \(3\sqrt{2}\), so \(\sqrt{2}+\sqrt{18}=\sqrt{2}+3\sqrt{2}=4\sqrt{2}\)

- Simplify each radical expression.

- Add or subtract expressions with equal radicands.

Add \(5\sqrt{12}+2\sqrt{3}\).

Solution

We can rewrite \(5\sqrt{12}\) as \(5\sqrt{4\times3}\). According the product rule, this becomes \(5\sqrt{4}\sqrt{3}\). The square root of \(\sqrt{4}\) is \(2\), so the expression becomes \(5\times2\sqrt{3}\), which is \(10\sqrt{3}\). Now we can the terms have the same radicand so we can add.

\[10\sqrt{3}+2\sqrt{3}=12\sqrt{3} \nonumber\]

Subtract \(20\sqrt{72a^3b^4c}-14\sqrt{8a^3b^4c}\)

Solution

Rewrite each term so they have equal radicands.

\[\begin{align*} 20\sqrt{72a^3b^4c} &= 20\sqrt{9}\sqrt{4}\sqrt{2}\sqrt{a}\sqrt{a^2}\sqrt{(b^2)^2}\sqrt{c}\\ &= 20(3)(2)|a|b^2\sqrt{2ac}\\ &= 120|a|b^2\sqrt{2ac} \end{align*}\]

\[\begin{align*} 14\sqrt{8a^3b^4c} &= 14\sqrt{2}\sqrt{4}\sqrt{a}\sqrt{a^2}\sqrt{(b^2)^2}\sqrt{c}\\ &= 14(2)|a|b^2\sqrt{2ac}\\ &= 28|a|b^2\sqrt{2ac} \end{align*}\]

Now the terms have the same radicand so we can subtract.

\[120|a|b^2\sqrt{2ac}-28|a|b^2\sqrt{2ac}=92|a|b^2\sqrt{2ac}\]

- Add \(\sqrt{5}+6\sqrt{20}\)

- Subtract \(3\sqrt{80x}-4\sqrt{45x}\)

- Answer a

-

\(13\sqrt{5}\)

- Answer b

-

\(0\)

Using Rational Roots

Although square roots are the most common rational roots, we can also find cube roots, \(4^{th}\) roots, \(5^{th}\) roots, and more. Just as the square root function is the inverse of the squaring function, these roots are the inverse of their respective power functions.

Understanding \(n^{th}\) Roots

Suppose we know that \(a^3=8\). We want to find what number raised to the \(3^{rd}\) power is equal to \(8\). Since \(2^3=8\), we say that \(2\) is the cube root of \(8\).

The \(n^{th}\) root of \(a\) is a number that, when raised to the \(n^{th}\) power, gives a. For example, \(−3\) is the \(5^{th}\) root of \(−243\) because \({(-3)}^5=-243\). If \(a\) is a real number with at least one \(n^{th}\) root, then the principal \(n^{th}\) root of \(a\) has the same sign as \(a\).

The principal \(n^{th}\) root of \(a\) is written as \(\sqrt[n]{a}\), where \(n\) is a positive integer greater than or equal to \(2\). In the radical expression, \(n\) is called the index of the radical. Notice that when the index is not written, we know the index must be \(2\).

If \(a\) is a real number with at least one \(n^{th}\) root, then the principal \(n^{th}\) root of \(a\), written as \(\sqrt[n]{a}\), is the number with the same sign as \(a\) that, when raised to the \(n^{th}\) power, equals \(a\). The index of the radical is \(n\).

Simplify each of the following:

- \(\sqrt[5]{-32}\)

- \(\sqrt[4]{4}\times\sqrt[4]{1024}\)

- \(-\sqrt[3]{\dfrac{8x^6}{125}}\)

Solution

a. \(\sqrt[5]{-32}=-2\) because \((-2)^5=-32\)

b. First, express the product as a single radical expression. \(\sqrt[4]{4096}=8\) because \(8^4=4096\)

c. \[\begin{align*} &\dfrac{-\sqrt[3]{8x^6}}{\sqrt[3]{125}}\qquad \text{Write as quotient of two radical expressions}\\ &\dfrac{-2x^2}{5}\qquad \text{Simplify} \end{align*}\]

Simplify

- \(\sqrt[3]{-216}\)

- \(\dfrac{3\sqrt[4]{80}}{\sqrt[4]{5}}\)

- Answer a

-

\(-6\)

- Answer b

-

\(6\)

Using Rational Exponents

Radical expressions can also be written without using the radical symbol. To do this, we must change the radical symbols into fractional (rational) exponents.

We can also have rational exponents with numerators other than \(1\). The numerator of the exponent comes from the power of the radicand and the denominator is the index or \(n^{th}\) root.

Notice that the location of the power does not matter; it can be inside or outside of the radical since all of the properties of exponents that we learned for integer exponents also hold for rational exponents.

Rational exponents are another way to express principal \(n^{th}\) roots. The general form for converting between a radical expression with a radical symbol and one with a rational exponent is

\[a^{\tfrac{m}{n}}=(\sqrt[n]{a})^m=\sqrt[n]{a^m}\]

- Determine the power by looking at the numerator of the exponent.

- Determine the root by looking at the denominator of the exponent.

- Using the base as the radicand, raise the radicand to the power and use the root as the index.

Write \(343^{\tfrac{2}{3}}\) as a radical. Simplify.

Solution

The \(2\) tells us the power and the \(3\) tells us the root.

\(343^{\tfrac{2}{3}}={(\sqrt[3]{343})}^2=\sqrt[3]{{343}^2}\)

We know that \(\sqrt[3]{343}=7\) because \(7^3 =343\). Because the cube root is easy to find, it is easiest to find the cube root before squaring for this problem. In general, it is easier to find the root first and then raise it to a power.

\[343^{\tfrac{2}{3}}={(\sqrt[3]{343})}^2=7^2=49\]

Write \(\dfrac{4}{\sqrt[7]{a^2}}\) using a rational exponent.

Solution

The power is \(2\) and the root is \(7\), so the rational exponent will be \(\dfrac{2}{7}\). We get \(\dfrac{4}{a^{\tfrac{2}{7}}}\). Using properties of exponents, we get \(\dfrac{4}{\sqrt[7]{a^2}}=4a^{\tfrac{-2}{7}}\)

Simplify:

a. \(5(2x^{\tfrac{3}{4}})(3x^{\tfrac{1}{5}})\)

b. \(\left(\dfrac{16}{9}\right)^{-\tfrac{1}{2}}\)

Solution

a.

\[\begin{align*} &30x^{\tfrac{3}{4}}\: x^{\tfrac{1}{5}}\qquad \text{Multiply the coefficients}\\ &30x^{\tfrac{3}{4}+\tfrac{1}{5}}\qquad \text{Use properties of exponents}\\ &30x^{\tfrac{19}{20}}\qquad \text{Simplify} \end{align*}\]

b.

\[\begin{align*} &{\left(\dfrac{9}{16}\right)}^{\tfrac{1}{2}}\qquad \text{Use definition of negative exponents}\\ &\sqrt{\dfrac{9}{16}}\qquad \text{Rewrite as a radical}\\ &\dfrac{\sqrt{9}}{\sqrt{16}}\qquad \text{Use the quotient rule}\\ &\dfrac{3}{4}\qquad \text{Simplify} \end{align*}\]

- Write \(9^{\tfrac{5}{2}}\) as a radical. Simplify.

- Simplify \({(8x)}^{\tfrac{1}{3}}\left(14x^{\tfrac{6}{5}}\right)\)

- Write \(x\sqrt{{(5y)}^9}\) using a rational exponent.

- Answer a

-

\({(\sqrt{9})}^5=3^5=243\)

- Answer b

-

\(28x^{\tfrac{23}{15}}\)

- Answer c

-

\(x(5y)^{\dfrac{9}{2}}\)

Key Concepts

- The principal square root of a number \(a\) is the nonnegative number that when multiplied by itself equals \(a\).

- If \(a\) and \(b\) are nonnegative, the square root of the product \(ab\) is equal to the product of the square roots of \(a\) and \(b\).

- If \(a\) and \(b\) are nonnegative, the square root of the quotient \(\dfrac{a}{b}\) is equal to the quotient of the square roots of \(a\) and \(b\).

- We can add and subtract radical expressions if they have the same radicand and the same index.

- Radical expressions written in simplest form do not contain a radical in the denominator. To eliminate the square root radical from the denominator, multiply both the numerator and the denominator by the conjugate of the denominator.

- The principal \(n^{th}\) root of \(a\) is the number with the same sign as \(a\) that when raised to the \(n^{th}\) power equals \(a\). These roots have the same properties as square roots.

- Radicals can be rewritten as rational exponents and rational exponents can be rewritten as radicals.

- The properties of exponents apply to rational exponents.