4.2: Multiplicative Group of Complex Numbers

- Page ID

- 81051

The complex numbers are defined as

\[ {\mathbb C} = \{ a + bi : a, b \in {\mathbb R} \}\text{,} \nonumber \]

where \(i^2 = -1\text{.}\) If \(z = a + bi\text{,}\) then \(a\) is the real part of \(z\) and \(b\) is the imaginary part of \(z\text{.}\)

To add two complex numbers \(z=a+bi\) and \(w= c+di\text{,}\) we just add the corresponding real and imaginary parts:

\[ z + w=(a + bi ) + (c + di) = (a + c) + (b + d)i\text{.} \nonumber \]

Remembering that \(i^2 = -1\text{,}\) we multiply complex numbers just like polynomials. The product of \(z\) and \(w\) is

\[ (a + bi )(c + di) = ac + bdi^2 + adi + bci = (ac -bd) +(ad + bc)i\text{.} \nonumber \]

Every nonzero complex number \(z = a +bi\) has a multiplicative inverse; that is, there exists a \(z^{-1} \in {\mathbb C}^\ast\) such that \(z z^{-1} = z^{-1} z = 1\text{.}\) If \(z = a + bi\text{,}\) then

\[ z^{-1} = \frac{a-bi}{ a^2 + b^2 }\text{.} \nonumber \]

The complex conjugate of a complex number \(z = a + bi\) is defined to be \(\overline{z} = a- bi\text{.}\) The absolute value or modulus of \(z = a + bi\) is \(|z| = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}\text{.}\)

Let \(z = 2 + 3i\) and \(w = 1-2i\text{.}\)

Solution

Then

\[ z + w = (2 + 3i) + (1 - 2i) = 3 + i \nonumber \]

and

\[ z w = (2 + 3i)(1 - 2i ) = 8 - i\text{.} \nonumber \]

Also,

\begin{align*} z^{-1} & = \frac{2}{13} - \frac{3}{13}i\\ |z| & = \sqrt{13}\\ \overline{z} & = 2-3i\text{.} \end{align*}

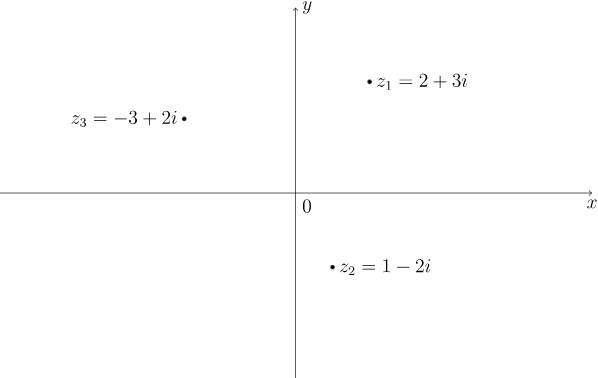

\(Figure \text { } 4.17.\) Rectangular coordinates of a complex number

There are several ways of graphically representing complex numbers. We can represent a complex number \(z = a +bi\) as an ordered pair on the \(xy\) plane where \(a\) is the \(x\) (or real) coordinate and \(b\) is the \(y\) (or imaginary) coordinate. This is called the rectangular or Cartesian representation. The rectangular representations of \(z_1 = 2 + 3i\text{,}\) \(z_2 = 1 - 2i\text{,}\) and \(z_3 = - 3 + 2i\) are depicted in \(Figure \text { } 4.17\).

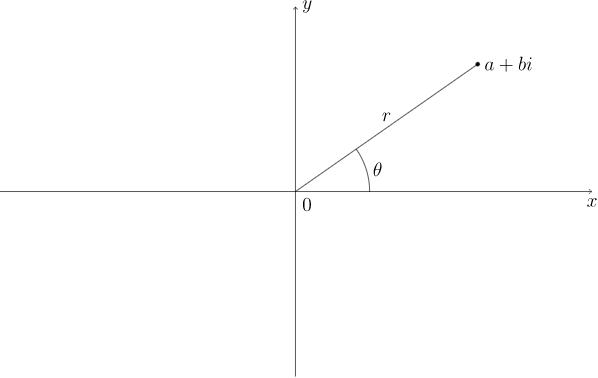

\(Figure \text { } 4.18.\) Polar coordinates of a complex number

Nonzero complex numbers can also be represented using polar coordinates. To specify any nonzero point on the plane, it suffices to give an angle \(\theta\) from the positive \(x\) axis in the counterclockwise direction and a distance \(r\) from the origin, as in \(Figure \text { } 4.18\). We can see that

\[ z = a + bi = r( \cos \theta + i \sin \theta)\text{.} \nonumber \]

Hence,

\[ r = |z| = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} \nonumber \]

and

\begin{align*} a & = r \cos \theta\\ b & = r \sin \theta\text{.} \end{align*}

We sometimes abbreviate \(r( \cos \theta + i \sin \theta)\) as \(r \cis \theta\text{.}\) To assure that the representation of \(z\) is well-defined, we also require that \(0^{\circ} \leq \theta \lt 360^{\circ}\text{.}\) If the measurement is in radians, then \(0 \leq \theta \lt2 \pi\text{.}\)

Suppose that \(z = 2 \cis 60^{\circ}\text{.}\) Then

\[ a = 2 \cos 60^{\circ} = 1 \nonumber \]

and

\[ b = 2 \sin 60^{\circ} = \sqrt{3}\text{.} \nonumber \]

Solution

Hence, the rectangular representation is \(z = 1+\sqrt{3}\, i\text{.}\)

Conversely, if we are given a rectangular representation of a complex number, it is often useful to know the number's polar representation. If \(z = 3 \sqrt{2} - 3 \sqrt{2}\, i\text{,}\) then

\[ r = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} = \sqrt{36 } = 6 \nonumber \]

and

\[ \theta = \arctan \left( \frac{b}{a} \right) = \arctan( - 1) = 315^{\circ}\text{,} \nonumber \]

so \(3 \sqrt{2} - 3 \sqrt{2}\, i=6 \cis 315^{\circ}\text{.}\)

The polar representation of a complex number makes it easy to find products and powers of complex numbers. The proof of the following proposition is straightforward and is left as an exercise.

Let \(z = r \cis \theta\) and \(w = s \cis \phi\) be two nonzero complex numbers. Then

\[ zw = r s \cis( \theta + \phi)\text{.} \end{equation*

If \(z = 3 \cis( \pi / 3 )\) and \(w = 2 \cis(\pi / 6 )\text{,}\)

Solution

then \(zw = 6 \cis( \pi / 2 ) = 6i\text{.}\)

Let \(z = r \cis \theta\) be a nonzero complex number. Then

\[ [r \cis \theta ]^n = r^n \cis( n \theta) \nonumber \]

for \(n = 1, 2, \ldots\text{.}\)

- Proof

-

We will use induction on \(n\text{.}\) For \(n = 1\) the theorem is trivial. Assume that the theorem is true for all \(k\) such that \(1 \leq k \leq n\text{.}\) Then

\begin{align*} z^{n+1} & = z^n z\\ & = r^n( \cos n \theta + i \sin n \theta ) r( \cos \theta + i\sin \theta )\\ & = r^{n+1} [( \cos n \theta \cos \theta - \sin n \theta \sin \theta ) + i ( \sin n \theta \cos \theta + \cos n \theta \sin \theta)]\\ & = r^{n+1} [ \cos( n \theta + \theta) + i \sin( n \theta + \theta) ]\\ & = r^{n+1} [ \cos( n +1) \theta + i \sin( n+1) \theta ]\text{.} \end{align*}

Suppose that \(z= 1+i\) and we wish to compute \(z^{10}\text{.}\)

Solution

Rather than computing \((1 + i)^{10}\) directly, it is much easier to switch to polar coordinates and calculate \(z^{10}\) using DeMoivre's Theorem:

\begin{align*} z^{10} & = (1+i)^{10}\\ & = \left( \sqrt{2} \cis \left( \frac{\pi }{4} \right) \right)^{10}\\ & = ( \sqrt{2}\, )^{10} \cis \left( \frac{5\pi }{2} \right)\\ & = 32 \cis \left( \frac{\pi }{2} \right)\\ & = 32i\text{.} \end{align*}

The Circle Group and the Roots of Unity

The multiplicative group of the complex numbers, \({\mathbb C}^*\text{,}\) possesses some interesting subgroups. Whereas \({\mathbb Q}^*\) and \({\mathbb R}^*\) have no interesting subgroups of finite order, \({\mathbb C}^*\) has many. We first consider the circle group,

\[ {\mathbb T} = \{ z \in {\mathbb C} : |z| = 1 \}\text{.} \nonumber \]

The following proposition is a direct result of Proposition 4.20.

The circle group is a subgroup of \({\mathbb C}^*\text{.}\)

Although the circle group has infinite order, it has many interesting finite subgroups. Suppose that \(H = \{ 1, -1, i, -i \}\text{.}\) Then \(H\) is a subgroup of the circle group. Also, \(1\text{,}\) \(-1\text{,}\) \(i\text{,}\) and \(-i\) are exactly those complex numbers that satisfy the equation \(z^4 = 1\text{.}\) The complex numbers satisfying the equation \(z^n=1\) are called the \(n\)th roots of unity.

If \(z^n = 1\text{,}\) then the \(n\)th roots of unity are

\[ z = \cis\left( \frac{2 k \pi}{n } \right)\text{,} \nonumber \]

where \(k = 0, 1, \ldots, n-1\text{.}\) Furthermore, the \(n\)th roots of unity form a cyclic subgroup of \({\mathbb T}\) of order \(n\)

- Proof

-

By DeMoivre's Theorem,

\[ z^n = \cis \left( n \frac{2 k \pi}{n } \right) = \cis( 2 k \pi ) = 1\text{.} \nonumber \]

The \(z\)'s are distinct since the numbers \(2 k \pi /n\) are all distinct and are greater than or equal to 0 but less than \(2 \pi\text{.}\) The fact that these are all of the roots of the equation \(z^n=1\) follows from from Corollary 17.9, which states that a polynomial of degree \(n\) can have at most \(n\) roots. We will leave the proof that the \(n\)th roots of unity form a cyclic subgroup of \({\mathbb T}\) as an exercise.

A generator for the group of the \(n\)th roots of unity is called a primitive \(n\)th root of unity.

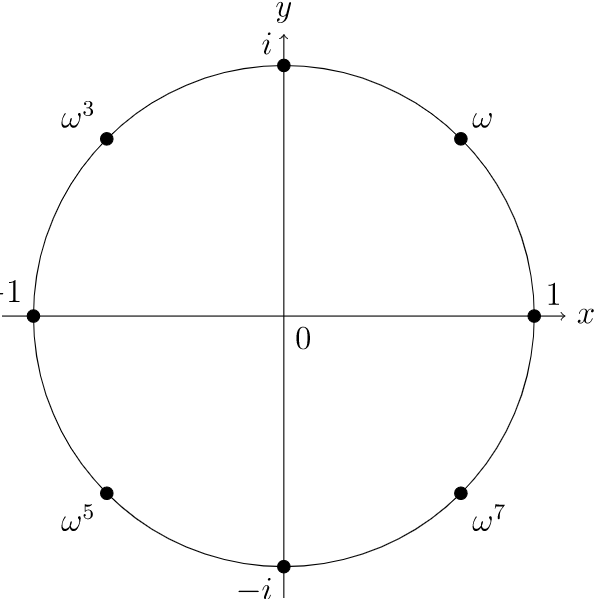

The 8th roots of unity can be represented as eight equally spaced points on the unit circle (\(Figure \text { } 4.27\)).

Solution

The primitive 8th roots of unity are

\begin{align*} \omega & = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} + \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} i\\ \omega^3 & = -\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} + \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} i\\ \omega^5 & = -\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} i\\ \omega^7 & = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} - \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}i\text{.} \end{align*}

\(Figure \text { } 4.27.\) 8th roots of unity