5.1: Limits

- Page ID

- 22664

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Let \(A \subset \mathbb{R}\) and let \(x\) be a limit point of \(A .\) In the following, we will let \(S(A, x)\) denote the set of all convergent sequences \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I}\) such that \(x_{n} \in A\) for all \(n \in I, x_{n} \neq x\) for all \(n \in I,\) and \(\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} x_{n}=x .\) We will let \(S^{+}(A, x)\) be the subset of \(S(A, x)\) of sequences \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I}\) for which \(x_{n}>x\) for all \(n \in I\) and \(S^{-}(A, x)\) be the subset of \(S(A, x)\) of sequences \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I}\) for which \(x_{n}<x\) for all \(n \in I .\)

Let \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}, L \in \mathbb{R},\) and suppose \(a\) is a limit point of \(D .\) We say the limit of \(f\) as \(x\) approaches \(a\) is \(L,\) denoted

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L ,\]

if for every sequence \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I} \in S(D, a)\),

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=L .\]

If \(S^{+}(D, a) \neq \emptyset,\) we say the limit from the right of \(f\) as \(x\) approaches \(a\) is \(L,\) denoted

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a+} f(x)=L ,\]

if for every sequence \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I} \in S^{+}(D, a)\),

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=L ,\]

and, if \(S^{-}(D, a) \neq \emptyset,\) we say the limit from the left of \(f\) as \(x\) approaches \(a\) is \(L,\) denoted

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a-} f(x)=L ,\]

if for every sequence \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I} \in S^{-}(D, a)\),

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=L .\]

We may also denote

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\]

by writing

\[f(x) \rightarrow L \text { as } x \rightarrow a .\]

Similarly, we may denote

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a^{+}} f(x)=L\]

by writing

\[f(x) \rightarrow L \text { as } x \downarrow a\]

and

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a^{-}} f(x)=L\]

by writing

\[f(x) \rightarrow L \text { as } x \uparrow a\]

We also let

\[f(a+)=\lim _{x \rightarrow a^{+}} f(x)\]

and

\[f(a-)=\lim _{x \rightarrow a^{-}} f(x).\]

It should be clear that if \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\) and \(S^{+}(D, a) \neq \emptyset,\) then \(f(a+)=L\). Similarly, if \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\) and \(S^{-}(D, a) \neq \emptyset,\) then \(f(a-)=L\).

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(a\) is a limit point of \(D\). If \(f(a-)=f(a+)=L,\) then \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\).

- Proof

-

Suppose \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n=m}^{\infty} \in S(D, a) .\) Let

\[J^{-}=\left\{n: n \in \mathbb{Z}, x_{n}<a\right\}\]

and

\[J^{+}=\left\{n: n \in \mathbb{Z}, x_{n}>a\right\}.\]

Suppose \(J^{-}\) is empty or finite and let \(k=m-1\) if \(J^{-}=\emptyset\) and, otherwise, let \(k\) be the largest integer in \(J^{-} .\) Then \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n=k+1}^{\infty} \in S^{+}(D, a),\) and so

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=f(a+)=L.\]

A similar argument shows that if \(J^{+}\) is empty or finite, then

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=f(a-)=L.\]

If neither \(J^{-}\) nor \(J^{+}\) is finite or empty, then \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in J}-\) and \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in J}+\) are subsequences of \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n=m}^{\infty}\) with \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in J^{-}} \in S^{-}(D, a)\) and \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in J+} \in S^{+}(D, a) .\) Hence, given any \(\epsilon>0,\) we may find integers \(N\) and \(M\) such that

\[\left|f\left(x_{n}\right)-L\right|<\epsilon\]

whenever \(n \in\left\{j: j \in J^{-}, j>N\right\}\) and

\[\left|f\left(x_{n}\right)-L\right|<\epsilon\]

whenever \(n \in\left\{j: j \in J^{+}, j>M\right\} .\) Let \(P\) be the larger of \(N\) and \(M .\) Since \(J^{-} \cup J^{+}=\left\{j: j \in \mathbb{Z}^{+}, j \geq m\right\},\) it follows that

\[\left|f\left(x_{n}\right)-L\right|<\epsilon\]

whenever \(n>P .\) Hence \(\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=L,\) and so \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\). \(\quad\) Q.E.D.

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D,\) and \(f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). If \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\) and \(\alpha \in \mathbb{R},\) then

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a} \alpha f(x)=\alpha L.\]

- Proof

-

Suppose \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I} \in S(D, a) .\) Then

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} \alpha f\left(x_{n}\right)=\alpha \lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=\alpha L.\]

Hence \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} \alpha f(x)=\alpha L\). \(\quad\) Q.E.D.

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(g: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R} .\) If \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\) and \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} g(x)=M,\) then

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a}(f(x)+g(x))=L+M.\]

- Proof

-

Suppose \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I} \in S(D, a) .\) Then

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left(f\left(x_{n}\right)+g\left(x_{n}\right)\right)=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)+\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} g\left(x_{n}\right)=L+M.\]

Hence \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a}(f(x)+g(x))=L+M\). \(\quad\) Q.E.D.

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(g: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R} .\) If \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\) and \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} g(x)=M,\) then

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x) g(x)=L M.\]

Prove the previous proposition.

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), \(g: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(g(x) \neq 0\) for all \(x \in D .\) If \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L, \lim _{x \rightarrow a} g(x)=M,\) and \(M \neq 0,\) then

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}=\frac{L}{M}.\]

Prove the previous proposition.

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(f(x) \geq 0\) for all \(x \in D .\) If \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L,\) then

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a} \sqrt{f(x)}=\sqrt{L}.\]

Prove the previous proposition.

Given \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(A \subset D,\) we let

\[f(A)=\{y: y=f(x) \text { for some } x \in A\}.\]

In particular, \(f(D)\) denotes the range of \(f\).

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, E \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D, g: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), \(f: E \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(g(D) \subset E .\) Moreover, suppose \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} g(x)=b\) and, for some \(\epsilon>0\), \(g(x) \neq b\) for all \(x \in(a-\epsilon, a+\epsilon) \cap D .\) If \(\lim _{x \rightarrow b} f(x)=L,\) then

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f \circ g(x)=L.\]

- Proof

-

Suppose \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I} \in S(D, a) .\) Then

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} g\left(x_{n}\right)=b.\]

Let \(N \in \mathbb{Z}^{+}\) such that \(\left|x_{n}-a\right|<\epsilon\) whenever \(n>N .\) Then

\[\left\{g\left(x_{n}\right)\right\}_{n=N+1}^{\infty} \in S(E, b),\]

so

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(g\left(x_{n}\right)\right)=L.\]

Thus \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f \circ g(x)=L\). \(\quad\) Q.E.D.

Let

\[g(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{0,} & {\text { if } x \neq 0,} \\ {1,} & {\text { if } x=0.}\end{array}\right.\]

If \(f(x)=g(x),\) then

\[f \circ g(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{1,} & {\text { if } x \neq 0,} \\ {0,} & {\text { if } x=0.}\end{array}\right.\]

Hence \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} f \circ g(x)=1,\) although \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} g(x)=0\) and \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} f(x)=0\).

5.1.1 Limits of Polynomials and Rational Functions

If \(c \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is given by \(f(x)=c\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), then clearly \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=c\) for any \(a \in \mathbb{R}\).

Suppose \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is defined by \(f(x)=x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R} .\) If, for any \(a \in \mathbb{R},\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I} \in S(\mathbb{R}, a),\) then

\[\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} x_{n}=a.\]

Hence \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} x=a\).

Suppose \(n \in \mathbb{Z}^{+}\) and \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is defined by \(f(x)=x^{n}\). Then

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=\lim _{x \rightarrow a} x^{n}=\prod_{i=1}^{n} \lim _{x \rightarrow a} x=a^{n}.\]

If \(n \in \mathbb{Z}, n \geq 0,\) and \(b_{0}, b_{1}, \ldots, b_{n}\) are real numbers with \(b_{n} \neq 0,\) then we call the function \(p: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) defined by

\[p(x)=b_{n} x^{n}+b_{n-1} x^{n-1}+\cdots+b_{1} x+b_{0}\]

a polynomial of degree \(n\).

Show that if \(f\) is a polynomial and \(a \in \mathbb{R},\) then \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=f(a)\).

Suppose \(p\) and \(q\) are polynomials and

\[D=\{x: x \in \mathbb{R}, q(x) \neq 0\}.\]

We call the function \(r: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) defined by

\[r(x)=\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}\]

a rational function.

Show that if \(f\) is a rational function and \(a\) is in the domain of \(f,\) then \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=f(a)\).

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a \in D\) is a limit point of \(D,\) and \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\). If \(E=D \backslash\{a\}\) and \(g: E \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is defined by \(g(x)=f(x)\) for all \(x \in E,\) show that \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} g(x)=L .\)

Evaluate

\[\lim _{x \rightarrow 1} \frac{x^{5}-1}{x^{3}-1}.\]

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}, g: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), \(h: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(f(x) \leq h(x) \leq g(x)\) for all \(x \in D .\) If \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\) and \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} g(x)=L,\) show that \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} h(x)=L .\) (This is the squeeze theorem for limits of functions.)

Note that the above results which have been stated for limits will hold as well for the appropriate one-sided limits, that is, limits from the right or from the left.

Suppose

\[f(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{x+1,} & {\text { if } x<0,} \\ {4,} & {\text { if } x=0,} \\ {x^{2},} & {\text { if } x>0.}\end{array}\right.\]

Evaluate \(f(0), f(0-),\) and \(f(0+) .\) Does \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} f(x)\) exist?

5.1.2 Equivalent Definitions

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D,\) and \(f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). Then \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\) if and only if for every \(\epsilon>0\) there exists a \(\delta>0\) such that

\[|f(x)-L|<\epsilon \text { whenever } x \neq a \text { and } x \in(a-\delta, a+\delta) \cap D.\]

- Proof

-

Suppose \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L .\) Suppose there exists an \(\epsilon>0\) such that for every \(\delta>0\) there exists \(x \in(a-\delta, a+\delta) \cap D, x \neq a,\) for which \(|f(x)-L| \geq \epsilon\). For \(n=1,2,3, \ldots,\) choose

\[x_{n} \in\left(a-\frac{1}{n}, a+\frac{1}{n}\right) \cap D,\]

\(x_{n} \neq a,\) such that \(\left|f\left(x_{n}\right)-L\right| \geq \epsilon .\) Then \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n=1}^{\infty} \in S(D, a),\) but \(\left\{f\left(x_{n}\right)\right\}_{n=1}^{\infty}\) does not converge to \(L,\) contradicting the assumption that \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L\).

Now suppose that for every \(\epsilon>0\) there exists \(\delta>0\) such that \(|f(x)-L|<\epsilon\) whenever \(x \neq a\) and \(x \in(a-\delta, a+\delta) \cap D .\) Let \(\left\{x_{n}\right\}_{n \in I} \in S(D, a) .\) Given \(\epsilon>0\), let \(\delta>0\) be such that \(|f(x)-L|<\epsilon\) whenever \(x \neq a\) and \(x \in(a-\delta, a+\delta) \cap D .\) Choose \(N \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(\left|x_{n}-a\right|<\delta\) whenever \(n>N .\) Then \(\left|f\left(x_{n}\right)-L\right|<\epsilon\) for all \(n>N .\) Hence \(\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} f\left(x_{n}\right)=L,\) and so \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=L .\) \(\quad\) Q.E.D.

The proofs of the next two propositions are analogous.

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(S^{-}(D, a) \neq \emptyset .\) Then \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a^{-}} f(x)=L\) if and only if for every \(\epsilon>0\) there exists a \(\delta>0\) such that

\[|f(x)-L|<\epsilon \text { whenever } x \in(a-\delta, a) \cap D.\]

Suppose \(D \subset \mathbb{R}, a\) is a limit point of \(D, f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R},\) and \(S^{+}(D, a) \neq \emptyset .\) Then \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a^{+}} f(x)=L\) if and only if for every \(\epsilon>0\) there exists a \(\delta>0\) such that

\[|f(x)-L|<\epsilon \text { whenever } x \in(a, a+\delta) \cap D.\]

5.1.3 Examples

Define \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) by

\[f(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{1,} & {\text { if } x \text { is rational, }} \\ {0,} & {\text { if } x \text { is irrational. }}\end{array}\right.\]

Let \(a \in \mathbb{R} .\) Since every open interval contains both rational and irrational numbers, for any \(\delta>0\) and any choice of \(L \in \mathbb{R},\) there will exist \(x \in(a-\delta, a+\delta),\) \(x \neq a,\) such that

\[|f(x)-L| \geq \frac{1}{2}.\]

Hence \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)\) does not exist for any real number \(a\).

Define \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) by

\[f(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{x,} & {\text { if } x \text { is rational, }} \\ {0,} & {\text { if } x \text { is irrational. }}\end{array}\right.\]

Then \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} f(x)=0\) since, given \(\epsilon>0,|f(x)|<\epsilon\) provided \(|x|<\epsilon\).

Show that if \(f\) is as given in the previous example and \(a \neq 0\), then \(\lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)\) does not exist.

Define \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) by

\[f(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{\frac{1}{q},} & {\text { if } x \text { is rational and } x=\frac{p}{q},} \\ {0,} & {\text { if } x \text { is irrational, }}\end{array}\right.\]

where \(p\) and \(q\) are taken to be relatively prime integers with \(q>0,\) and we take \(q=1\) when \(x=0 .\) Show that, for any real number \(a, \lim _{x \rightarrow a} f(x)=0\).

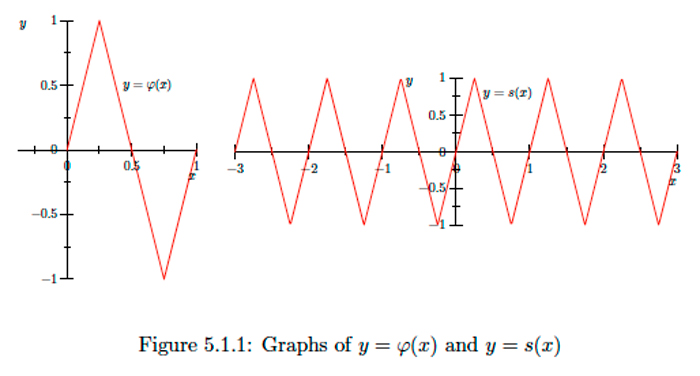

Define \(\varphi:[0,1] \rightarrow[-1,1]\) by

\[\varphi(x)=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{4 x,} & {\text { if } 0 \leq x \leq \frac{1}{4},} \\ {2-4 x,} & {\text { if } \frac{1}{4}<x<\frac{3}{4},} \\ {4 x-4,} & {\text { if } \frac{3}{4} \leq x \leq 1.}\end{array}\right.\]

Next define \(s: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) by \(s(x)=\varphi(x-\lfloor x\rfloor),\) where \(\lfloor x\rfloor\) denotes the largest integer less than or equal to \(x\) (that is, \(\lfloor x\rfloor\) is the floor of \(x\) ). The function \(s\) is an example of a sawtooth function. See the graphs of \(\varphi\) and \(s\) in Figure \(5.1 .1 .\) Note that for any \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\),

\[s([n, n+1])=[-1,1].\]

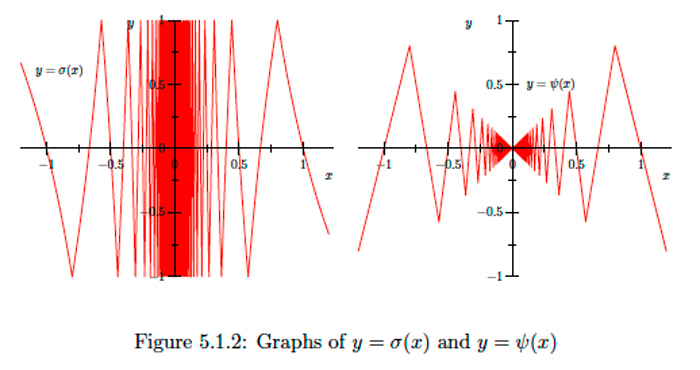

Now let \(D=\mathbb{R} \backslash\{0\}\) and define \(\sigma: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) by

\[\sigma(x)=s\left(\frac{1}{x}\right).\]

See the graph of \(\sigma\) in Figure \(5.1 .2 .\) Note that for any \(n \in \mathbb{Z}^{+}\),

\[\sigma\left(\left[\frac{1}{n+1}, \frac{1}{n}\right]\right)=s([n, n+1])=[-1,1].\]

Hence for any \(\epsilon>0, \sigma((0, \epsilon))=[-1,1],\) and so \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0^{+}} \sigma(x)\) does not exist. Similarly, neither \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0^{-}} \sigma(x)\) nor \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} \sigma(x)\) exist.

Let \(s\) be the sawtooth function of the previous example and let \(D=\mathbb{R} \backslash\{0\} .\) Define \(\psi: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) by

\[\psi(x)=x s\left(\frac{1}{x}\right).\]

See Figure 5.1 .2 for the graph of \(\psi .\) Then for all \(x \in D\),

\[-|x| \leq \psi(x) \leq|x|,\]

and so \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} \psi(x)=0\) by the squeeze theorem.

Let \(D \subset \mathbb{R}\) and \(f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{R} .\) We say \(f\) is bounded if there exists a real number \(B\) such that \(|f(x)| \leq B\) for all \(x \in D\).

Suppose \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is bounded. Show that \(\lim _{x \rightarrow 0} x f(x)=0\).