3.3: Intervals in Eⁿ

- Last updated

-

Sep 5, 2021

-

Save as PDF

-

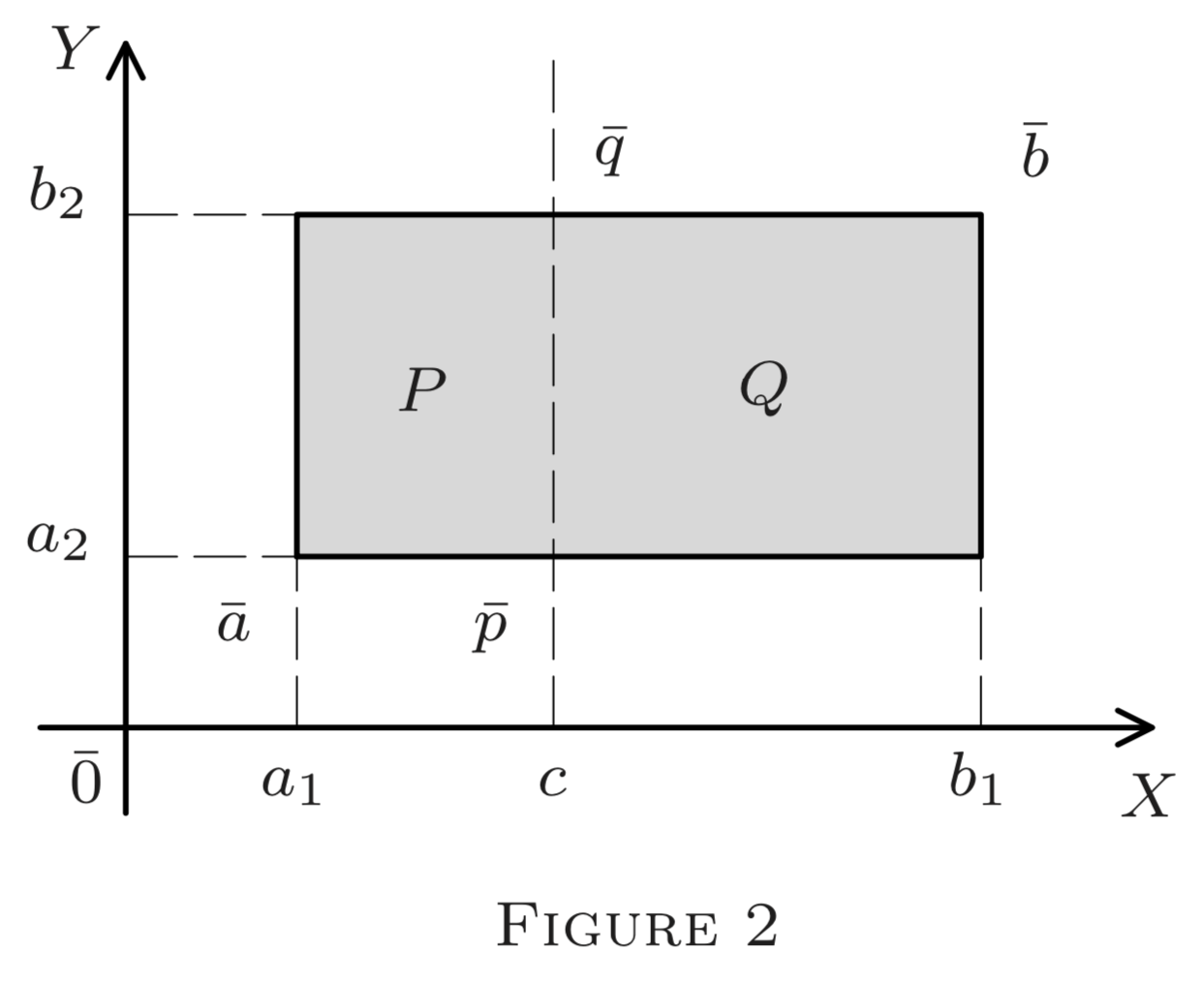

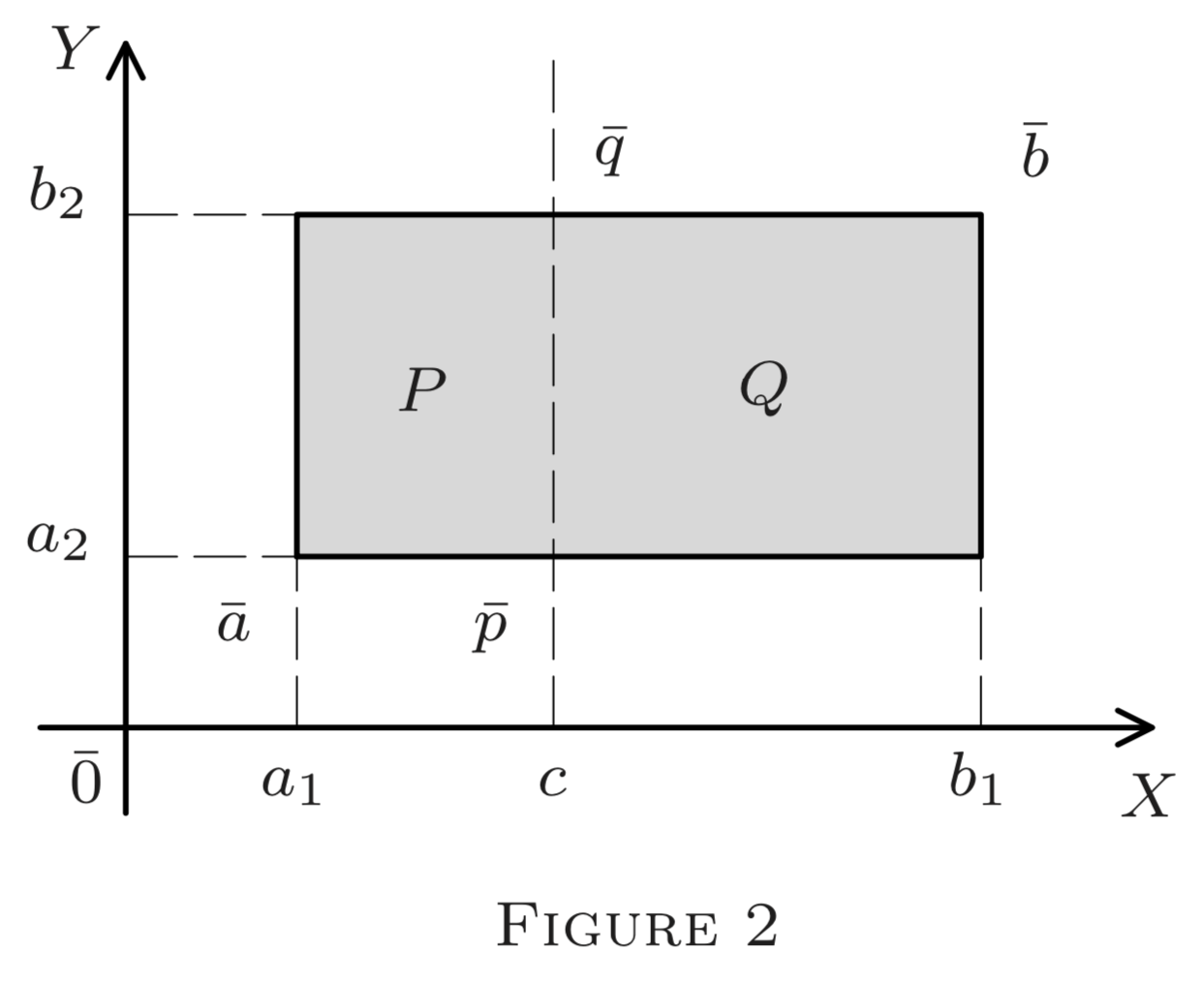

Consider the rectangle in shown in Figure 2. Its interior (without the perimeter consists of all points such that

i.e.,

Thus it is the Cartesian product of two line intervals, and To include also all or some sides, we would have to replace open intervals by closed, half-closed, or half-open ones. Similarly, Cartesian products of three line intervals yield rectangular parallelepipeds in We call such sets in intervals.

Definition

1. By an interval in we mean the Cartesian product of any intervals in (some may be open, some closed or half-open, etc.).

2. In particular, given

with

we define the open interval the closed interval the half-open interval and the half-closed interval as follows:

In all cases, and are called the endpoints of the interval. Their distance

is called its diagonal. The differences

are called its edge-lengths. Their product

is called the volume of the interval (in it is its area, in its length) .\) The point

is called its center or midpoint. The set difference

is called the boundary of any interval with endpoints and it consists of 2 "faces" defined in a natural manner. (How?)

We often denote intervals by single letters, e.g.. and write for "diagonal of and or vol for "volume of If all edge-lengths are equal, is called a cube (in a square). The interval is said to be degenerate iff for some in which case, clearly,

Note 1. We have iff the inequalities hold simultaneously for all This is impossible if for some similarly for the inequalities or . Thus a degenerate interval is empty, unless it is closed (in which case it contains and at least).

Note 2. In any interval ,

In we can split an interval into two subintervals and by drawing a line (see Figure 2 In this is done by a plane orthogonal to one of the axes of the form see §§4-6, Note 2 with In particular, if \right. the plane bisects the th edge of and so the th edge-length of and equals If is closed, so is or depending on our choice. (We may include the "partition" in or

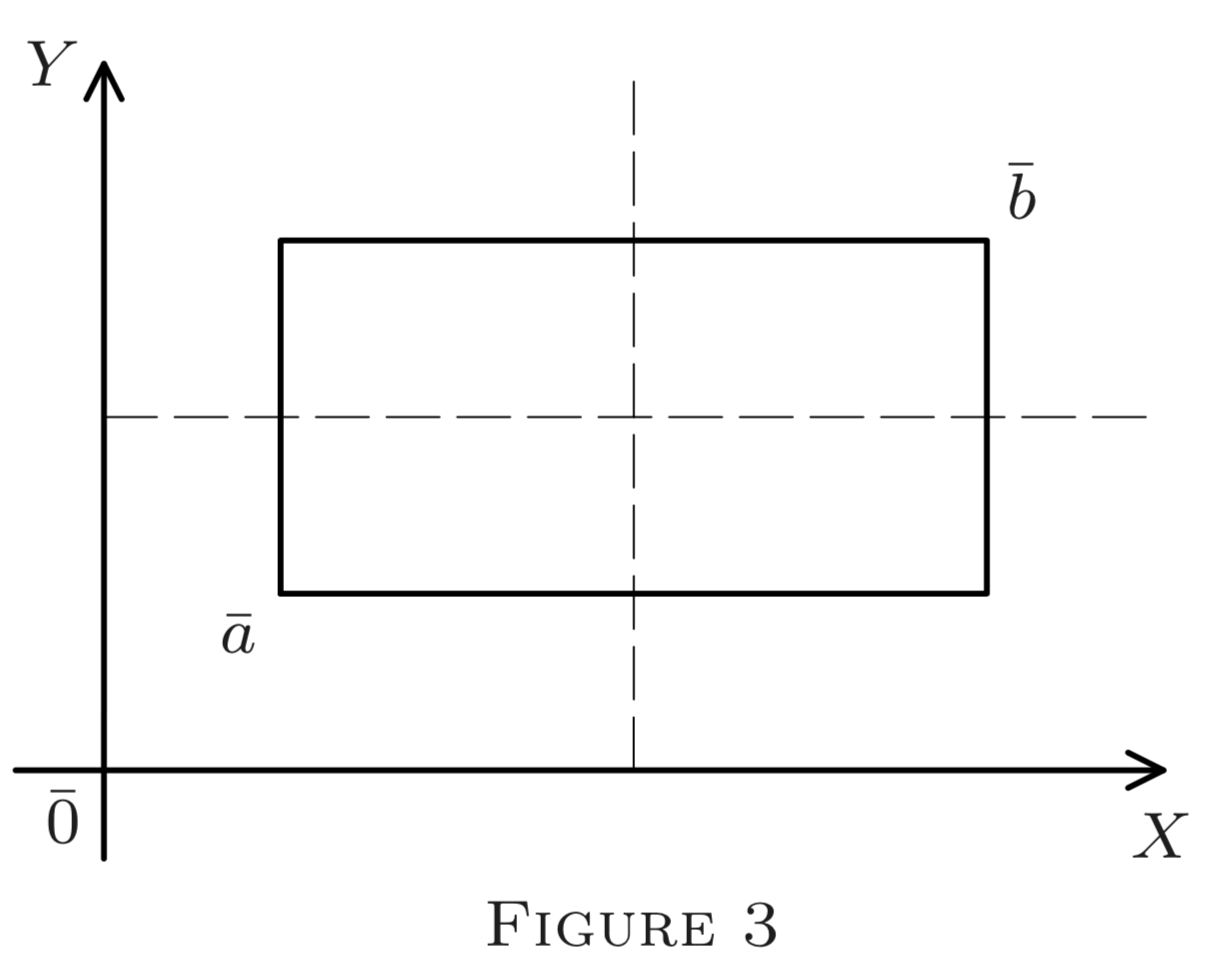

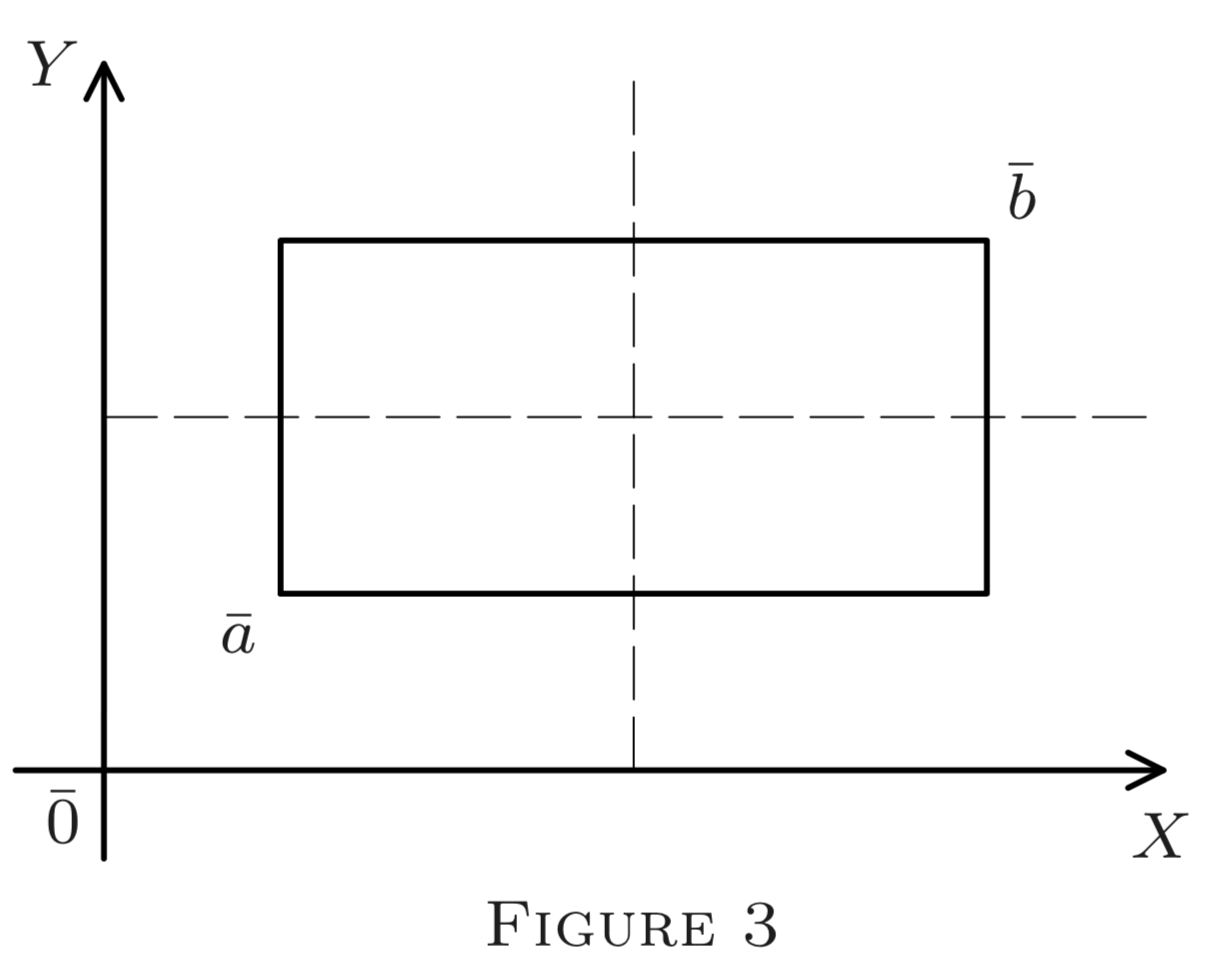

Now, successively draw planes The first plane bisects leaving the other edges of changed. The resulting two subintervals and then are cut by the plane bisecting the second edge in each of them. Thus we get four subintervals (see Figure 3 for . Each successive plane doubles the number of subintervals. After steps, we thus obtain disjoint intervals, with all edges bisected. Thus by Note the diagonal of each of them is

Note 3. If is closed then, as noted above, we can make any one (but only one of the subintervals closed by properly manipulating each step.

The proof of the following simple corollaries is left to the reader.

Corollary

No distance between two points of an interval exceeds its diagonal. That is,

Corollary

If an interval contains and then also .

corollary

Every nondegenerate interval in contains rational points, i.e., points whose coordinates are all rational.

(Hint: Use the density of rationals in for each coordinate separately.)