7.2: The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

- Page ID

- 83953

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

In the last section we defined the definite integral, \(\int_a^b f(t)dt\text{,}\) the signed area under the curve \(y= f(t)\) from \(t=a\) to \(t=b\text{,}\) as the limit of the area found by approximating the region with thinner and thinner rectangles. We also saw that we can easily find a reasonable approximation to the area using Excel to find such a sum with a fairly large number of rectangles.

In the trivial case where we have a constant function \(f(t)=c\) we can find the area of the area with a simple formula, \(\int_a^b c\ dt=c(b-a)=cb-ca\text{.}\) If we define an area function, \(F(x)\text{,}\) as the area under the curve \(y=f(t)\) from \(t=0\) to \(t=x\text{,}\) then the area function in this case is \(F(x)=c*x\text{.}\) We would like to be able to evaluate more integrals with a process like this, where we have a simple area function.

We shifted the independent variable from \(t\) for the function \(f\) to \(x\) for the function \(F\) because we have two independent variables in our discussion and we want to keep them separate to avoid confusion. We will consider \(f\) as a function of \(t\text{,}\) and want to find the area under the graph of \(f(t)\text{.}\) We will consider \(F\) as a function of \(x\text{,}\) and understand it as the area under the curve \(y=f(t)\) from some starting point \(t=a\) to \(t=x\text{.}\)

We start by exploring cases where we can justify an area function without using calculus. We will then look at some cases where we can experimentally verify the area function with Excel. Finally we will give the general rule for the area function, the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, and will give some justification.

Let \(f(t)=c\text{.}\) For a constant function, \(f(t)=c\text{,}\) the area under the curve will be the area of a rectangle of height \(c\) and width \(b-a\text{.}\) The obvious area function is \(F(x)=c*x\text{.}\)

Solution

Then

\[ \int_a^b c dt=F(b)-F(a)=c*b-c*a=c(b-a). \nonumber \]

It is worth noting that this formula gives "signed area." If c or b-a is negative, the "area" is negative.

Let \(f(t) = c*t\text{.}\) For a linear function, \(f(t) = c*t\text{,}\) the area under the curve from 0 to \(b\) will be the area of a triangle of height \(c*b\) and width \(b\text{.}\)

Solution

The obvious area function is \(F(x)=c*x^2/2\text{.}\) If \(a\) is also nonzero, the area is the difference of the areas of two triangles.

\[ \int_a^b c*t dt=F(b)-F(a)= \frac{c*b^2}{2}-\frac{c*a^2}{2}=\frac{c (b^2-a^2 )}{2}. \nonumber \]

As we consider finding area with Excel and Riemann sums, rather than use a right-hand rule for the rectangles, we are going to use a midpoint rule where we find the area of rectangles evaluated at the middle of each interval.

The right-hand rule uses an easier formula, so we used it first. For the ith rectangle we evaluate at \(x_i=a+i\Delta x\text{.}\) For the midpoint formula, we evaluate at the midpoint of the interval, at \(mid_i=a+i\Delta x-\Delta x/2\text{.}\) As the picture suggests, the midpoint formula gives a better approximation. The right-hand rule always overestimates an increasing function. The midpoint rule is exact for linear functions where the midpoint is the average value.

In both of the examples we have examined the area function has the original function as its derivative. We would like to use Excel to test a few more cases. In the worksheets we set up in the last section, SumArea is the area function we are looking for. We will plot the area function and use a best-fit curve to find the equation of the area function.

Repeat the last example, finding the area under \(f(x)=6x\text{,}\) with Excel. With a linear function we have use the following to produce an area function.

Solution

Column C has our list of \(t\) values in the center of each interval. Column D has the value of \(f(t)\) evaluated at those points. The area of the rectangle is the height \(f(mid_n)\) times the width, Interval width. SumArea is our running area function. When we plot the area function we have something that seems to be quadratic with leading coefficient \(c/2\) and very small linear and constant coefficients. In fact the linear and constant coefficients are zero up to a rounding factor for numbers of the size we are using.

This matches the result we had solving the problem with geometry. However, we can repeat the process with Excel and use functions of higher order.

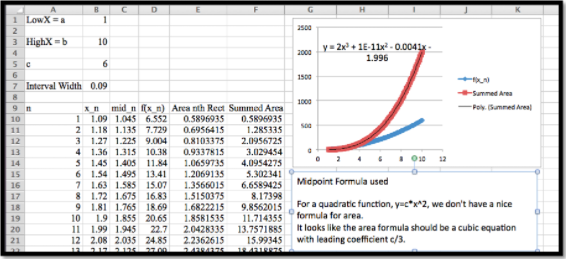

Find the area function when \(f(t) = 6t^2\text{.}\)

Solution

For this problem we essentially repeat the work of the previous example with a quadratic function for \(f(t)\text{.}\)

When we plot the area function we get a very good fit with a cubic function. Once again, allowing for the way best-fit curves may return small random values for coefficients that should be zero, we see that if \(f(t) =c*t^2\text{,}\) then the related area function is

\[ F(x)=c*t^3/3\text{.} \nonumber \]

Find the area when \(f(x)=6 x^3\text{.}\)

Solution

Once again, we can use Excel to produce an area function. The area function seems to be \(F(x)=1.5 x^4\text{.}\)

In all the examples above we note that the area function, \(F(x)\text{,}\) has \(f(x)\text{,}\) the curve we are finding the area under, as its derivative. Thus, in these cases, the area is an anti-derivative of \(f(x)\text{.}\) This observation generalizes to the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, which has two versions:

Let \(f(x)\) be a continuous function on the interval \([a, b]\text{.}\) On that interval define an area function by \(F(x)=\int_a^x f(t) dt\text{.}\) Then \(\frac{d}{dx} F(x)=f(x)\text{.}\)

Let \(f(x)\) be a continuous function on the interval \([a, b]\text{.}\) Suppose \(F(x)\) is any continuous, differentiable function with \(\frac{d}{dx} F(x)=f(x)\text{.}\) Then \(\int_a^b f(t) dt=F(b)-F(a)\text{.}\)

In practice we use the second version of the fundamental theorem to evaluate definite integrals. We find a function \(F(x)\) whose derivative is the integrand \(f(x)\) and then evaluate \(F(x)\) at the endpoints. It is easier to prove or justify the first version of the fundamental theorem. The basic argument notes that is \(F(x)=\int_a^xf(t) \ dt\text{,}\) then formally

\[ \frac{d}{dx} F(x)=\lim_{h\to 0} \frac{(F(x+h)-F(x))}{h}. \nonumber \]

But if \(h\) is small, \(F(x+h)-F(x)\) is approximately the area of a rectangle of height \(f(x)\) and with \(h\text{,}\) so the \(F'(x) = f(x)\text{.}\) We then note that any two anti-derivatives of a function differ by a constant.

In example 7.1.4 in the previous section, we used Riemann sums with 100 and 1000 intervals to approximate the area under \(y = x*(4-x)\) with \(x\) between 0 and 4. Find the area using the fundamental theorem of calculus,

Solution

We rewrite the curve as \(f(x) = 4x – x^2\) and note that one anti-derivative of \(f(x)\) is \(F(x) = 2 x^2 - x^3/3\text{.}\) Then

\[ \int_0^4 f(x)\ dx=F(4)-F(0)=\left(32-\frac{64}{3}\right)-(0)=10 \frac{2}{3}. \nonumber \]

To get the same answer to 4 decimal places, we needed to use 1000 intervals with Riemann sums. Clearly, it is easier to solve this problem with the fundamental theorem of calculus than to make an approximation with that many intervals.

Let \(f(x)=x^2 e^{-x}\text{.}\) We are told \(F(x)=(x^2+2 x+2) (-e^{-x})\) is an anti-derivative of \(f(x)\text{.}\) Verify the anti-derivative and find the area under the curve with \(x\) between 0 and 2.

Solution

Using the product rule,

\[ F'(x)=(2x+2) (-e^{-x}) + (x^2+2x+2) (e^{-x})=x^2 e^{-x}=f(x) \nonumber \]

The area is

\[ F(2) – F(0) = 10(-e^{-2}) – 2(e^{0}) = -2 – 10/e^2 = -3.3534 \nonumber \]

We also want to revisit our first three examples in light of the fundamental theorem if calculus. In all of those examples we used Excel to find a best fitting curve for an area function. We can now check our work by taking the derivative, adjusting parameters as needed to find an anti-derivative. For constant and linear functions we have already done the adjusting because we could find the area function from geometry.

Example 3a: Find the area function when \(f(t) = 6t^2\text{.}\)

Solution

We have already used Excel to find a best fitting curve.

We are thus suspicious that the anti-derivative should be a cubic polynomial. We need

\[ 6t^2=d/dt (at^3+bt^2+ct+d)=3at^2+2bt+c. \nonumber \]

Setting coefficients equal for each power, we see \(a = 2\) and \(b = c = 0\text{.}\) Thus our area function has the form \(F(t) = 2 t^3 + d\text{.}\) Since \(F(0)\) is the area of a region between \(t = 0\) and \(t = 0\text{,}\) we conclude \(d = 0\) and our area function is \(F(t) = 2 t^3\text{.}\)

Find the area when \(f(x) = 6 x^3\text{.}\)

Solution

Using Excel we guessed the area function \(F(x) = 1.5 x^4\text{.}\) We can now verify that the derivative of \(F(x)\) is \(f(x)\text{,}\) so we have found an anti-derivative.

It is worth noting that using the fundamental theorem to evaluate integrals requires us to be able to find an anti-derivative of a function. Finding an anti-derivative may be quite hard or even an impossible task. The method we have just used is often referred to as the “guess and check” method of finding anti-derivatives. We will look at methods of finding anti-derivatives in the next several sections.

class="Exercises: The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Problems

Let \(f(x) = 4 x + 5\text{.}\) We are told that \(F(x) = 2 x^2 + 5 x + 7\) is an anti-derivative.

- Verify that \(f(x)\) is a derivative of \(F(x)\text{.}\)

- Use the fundamental theorem of calculus to evaluate \(\int_1^5 f(x)\ dx\text{.}\)

- Approximate \(\int_1^5 f(x)\ dx\text{,}\) using Riemann sums and 100 intervals.

- Answer

-

- \[ F' (x)=\frac{d}{dx} (2 x^2+ 5 x + 7)=4x+5 \nonumber \]