8.6: Application - Treasury Bills and Commercial Papers

- Page ID

- 22115

Where does the government go to borrow money? The evening news you are watching announces that Canada’s national debt has ballooned from $458 billion in 2008 to over $654 billion in August 2012. This means the government has borrowed this money from somewhere. You begin to wonder where ... it can’t exactly walk into the country’s largest bank (RBC) and ask for a $654 billion loan! Although RBC is Canada's largest banking institution and in 2012 it ranked 70th on the Forbes Global 2000 list of the world's biggest public companies, it still does not have enough money to lend to the government. If a government cannot get a loan from a financial institution, then how do federal and provincial governments borrow money in such large amounts?

Treasury Bills: The Basics

The answer lies in treasury bills, better known as T-bills, which are short-term financial instruments that both federal and provincial governments issue with maturities no longer than one year. Approximately 27% of the national debt is borrowed through T-bills.

Who purchases these T-bills? It is a two-tiered process. First, major investment companies and banks purchase the T-bills in very large denominations (such as $1 million or $10 million). Then these organizations break the T-bills down into bite-size chunks (such as $1,000 denominations) and sell them to their customers and other investors like you and me, at a profit of course. In essence, it is you and I who finance the debt of Canada!

Here are some of the basics about T-bills:

- The Government of Canada regularly places T-bills up for auction every second Tuesday. Provincial governments issue them at irregular intervals.

- The most common terms for federal and provincial T-bills are 30 days, 60 days, 90 days, 182 days, and 364 days.

- T-bills do not earn interest. Instead, they are sold at a discount and redeemed at full value. This follows the principle of "buy low, sell high." The percentage by which the value of the T-bill grows from sale to redemption is called the yield or rate of return. From a mathematical perspective, the yield is calculated in the exact same way as an interest rate is calculated, and therefore the yield is mathematically substituted as the discount rate in all simple interest formulas. Up-to-date yields on T-bills can be found at www.bankofcanada.ca/en/rates/monmrt.html.

- The face value of a T-bill (also called par value) is the maturity value, payable at the end of the term. It includes both the principal and yield together.

- T-bills do not have to be retained by the initial investor throughout their entire term. At any point during a T-bill’s term, an investor is able to sell it to another investor through secondary financial markets. Prevailing yields on T-bills at the time of sale are used to calculate the price.

Commercial Papers - The Basics

A commercial paper (or paper for short) is the same as a T-bill except that it is issued by a large corporation instead of a government. It is an alternative to short-term bank borrowing for large corporations. Most of these large companies have solid credit ratings, meaning that investors bear very little risk that the face value will not be repaid upon maturity.

For a corporation, papers tend to be a cheaper source of financing than borrowing from a bank. The yields paid to investors are less than the interest rate the corporation is charged by the bank. The corporation can also make its financing even cheaper by offering the commercial paper directly to investors to avoid intermediary brokerage fees and charges. Finally, commercial papers are not subject to strict financial requirements and registration, such as stocks and bonds require; therefore, they pose easy access to funds in the short-term for a corporation.

Commercial papers carry the same properties as T-bills. The only fundamental differences lie in the term and the yield:

- The terms are usually less than 270 days but can range from 30 days to 364 days. The most typical terms are 30 days, 60 days, and 90 days.

- The yield on commercial papers tends to be slightly higher than on T-bills since corporations do carry a higher risk of default than governments.

How It Works

Mathematically, T-bills and commercial papers operate in the exact same way. The future value for both of these investment instruments is always known since it is the face value. Commonly, the two calculated variables are either the present value (price) or the yield (interest rate). The yield is explored later in this section. Follow these steps to calculate the price:

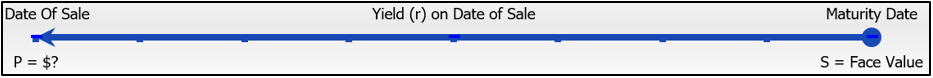

Step 1: The face value, yield, and time before maturity must be known. Draw a timeline if necessary, as illustrated below, and identify the following:

- The face value (\(S\)).

- The yield (\(r\)) on the date of the sale, which is always expressed annually. Remember that mathematically the yield is the same as the discount rate.

- The number of days (\(t\)) remaining between the date of the sale and the maturity date. Count the first day but not the last day. Express the number of days annually to match the annual yield.

Step 2: Apply Formula 8.2, rearranging and solving for the present value, which is the price of the T-bill or commercial paper. This price is always less than the face value.

Paths To Success

When you calculate the price of a T-bill or commercial paper, the only important pieces of information are the face value, the yield or discount rate on the date of sale, and how many days remain until maturity. Any prior history of the T-bill or commercial paper does not matter in any way. What the market rate was yesterday or last week or upon the date of issue does not impact today's price. Likewise, the number of days since the date of issue does not matter. What an investor paid for it three weeks ago is irrelevant. When calculating the price, pay attention only to the current market information and the future. Ignore the history!

- All other variables remaining stable, what happens to the price (present value) of a T-bill or commercial paper if the discount rate increases?

- An investor purchases a T-bill when the yield is 3%. A few months later, the investor sells the T-bill when the yield has dropped to 2%. Will the investor realize a yield of 3%, more than 3%, or less than 3% on the investment?

- Answer

-

- The price is lower because more yield must be realized on the investment.

- More than 3%. Since the T-bill yield is lower when sold, the price of the T-bill increases, resulting in the investor receiving more money on the investment. This raises the investor's return on investment

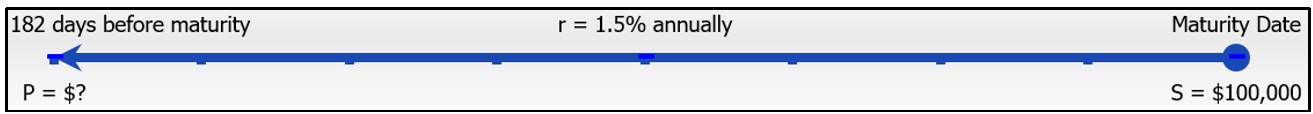

A Government of Canada 182-day issue T-bill has a face value of $100,000. Market yields on these T-bills are 1.5%. Calculate the price of the T-bill on its issue date.

Solution

Calculate the price that an investor will pay for the T-bill, or \(P\).

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The T-bill maturity value, term, and yield are known: \(S = \$100,000, r = 1.5\%, t = 182/365\)

How You Will Get There

Step 2:

Apply Formula 8.2, rearranging for \(P\).

Perform

Step 2:

\[\begin{align*} \$100,000 &= P\left (1 + 0.015 \times \dfrac{182}{365} \right )\\ P&= \dfrac{\$100,000}{1+(0.015)\left ( \dfrac{182}{365} \right )}\\ &= \$99,257.61 \end{align*} \nonumber \]

An investor will pay $99,257.61 for the T-bill. If the investor holds onto the T-bill until maturity, the investor realizes a yield of 1.5% and receives $100,000.

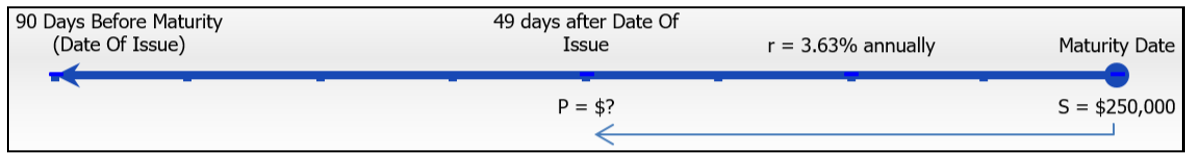

Pfizer Inc. issued a 90-day, $250,000 commercial paper on April 18 when the market rate of return was 3.1%. The paper was sold 49 days later when the market rate of return was 3.63%. Calculate the price of the commercial paper on its date of sale.

Solution

Calculate the price that an investor pays for the commercial paper on its date of sale, or \(P\).

What You Already Know

Step 1:

Note that the historical rate of return of 3.1% is irrelevant to the price of the commercial paper today. The number of days elapsed since the date of issue is also unimportant. The number of days before maturity is the key piece of information.

The commercial paper maturity value, term, and yield are: \(S = \$250,000, r = 3.63\%, t = 90 − 49 = 41\) days or 41/365

How You Will Get There

Step 2:

Apply Formula 8.2, rearranging for \(P\).

Perform

Step 2:

\[\begin{align*} \$250,000 &= P\left (1 + 0.0363 \times \dfrac{41}{365} \right )\\ P&= \dfrac{\$250,000}{1+(0.0363)\left ( \dfrac{41}{365} \right )}\\ &= \$248,984.76 \end{align*} \nonumber \]

An investor pays $248,984.76 for the commercial paper on the date of sale. If the investor holds onto the commercial paper for 41 more days (until maturity), the investor realizes a yield of 3.63% and receives $250,000.

How It Works

Calculating a Rate of Return: Sometimes the unknown value when working with T-bills and commercial papers is the yield, or rate of return. In these cases, follow these steps to solve the problem:

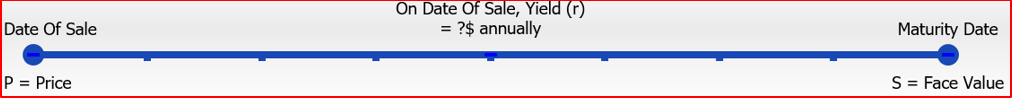

Step 1: The face value, price, and time before maturity must be known. Draw a timeline if necessary, as illustrated below, and identify:

- The face value (\(S\))

- The price on the date of the sale (\(P\))

- The number of days (\(t\)) remaining between the date of the sale and the maturity date. Count the first day but not the last day. Express the number of days annually so that the calculated yield will be annual.

Step 2: Apply Formula 8.3, \(I = S - P\), to calculate the interest earned during the investment.

Step 3: Apply Formula 8.1, \(I =Prt\), rearranging for \(r\) to solve for the interest rate (or yield or rate of return).

Paths To Success

When you solve for yield, you will almost always find that the purchase price has been rounded to two decimals. This means the calculation of the yield is based on an imprecise number. The results are likely to show small decimals such as 3.4005%. In this example, the most likely yield is 3.40% with the 0.0005% appearing because of rounding. Yields on T-bills and commercial papers typically do not have more than two decimal places, which means that decimals in the third position or more are most likely caused by a rounding error and should be rounded off to two decimals accordingly.

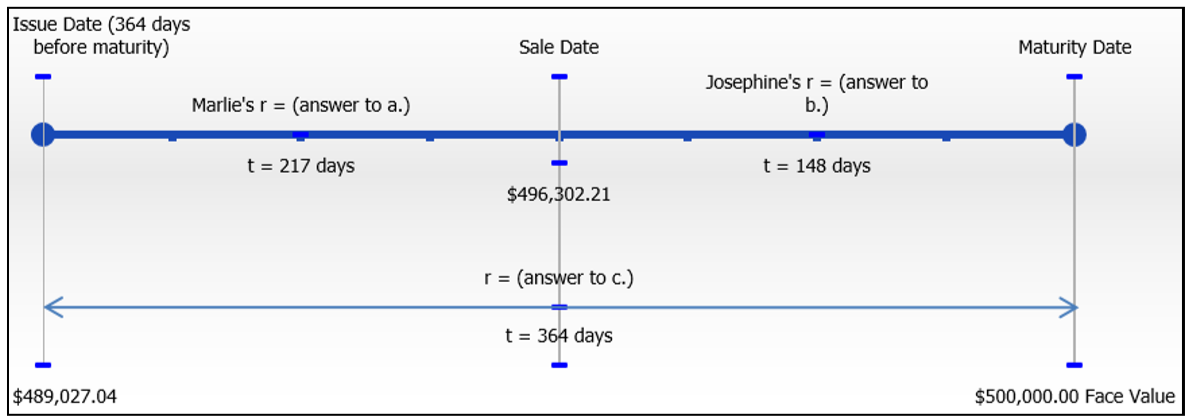

Marlie paid $489,027.04 on the date of issue for a $500,000 face value T-bill with a 364-day term. Marlie received $496,302.21 when he sold it to Josephine 217 days after the date of issue. Josephine held the T-bill until maturity. Determine the following:

- Marlie's actual rate of return

- Josephine's actual rate of return

- If Marlie held onto the T-bill for the entire 364 days instead of selling it to Josephine, what would his rate of return have been?

- Comment on the answers to (a) and (c).

Solution

Calculate three yields or rates of return (\(r\)) involving Marlie and the sale to Josephine, Josephine herself, and Marlie without the sale to Josephine. Afterwards, comment on the rate of return for Marlie with and without the sale.

What You Already Know

Step 1:

The present values, maturity value, and terms are known:

- Marlie with sale: \(P = \$489,027.04, S = \$496,302.21, t = 217/365\)

- Josephine: \(P = \$496,302.21, S = \$500,000.00, 364 − 217 = 147\) days remaining \(t = 147/365\)

- Marlie without sale: \(P = \$489,027.04, S = \$500,000.00, t = 364/365\)

How You Will Get There

Step 2:

For each situation, calculate the \(I\) by applying Formula 8.3.

Step 3:

For each situation, apply Formula 8.1, rearranging for \(r\).

Step 4:

Compare the answers for (a) and (c) and comment.

Perform

Step 2: Calculate \(I\)

- Marlie with sale to Josephine: \(I = \$496,302.21 − \$489,027.04 = \$7,275.17\)

- Josephine by herself: \(I = \$500,000.00 − \$496,302.21 = \$3,697.79\)

- Marlie without sale to Josephine: \(I = \$500,000.00 − \$489,027.04 = \$10,972.96\)

Step 3: Calculate \(r\)

- Marlie with sale to Josephine: \(r=\dfrac{\$ 7,275.17}{(\$ 489,027.04)\left(\dfrac{217}{365}\right)}=2.50 \%\)

- Josephine by herself: \(r=\dfrac{\$ 3,697.79}{(\$ 496,302.21)\left(\dfrac{147}{365}\right)}=1.85 \%\)

- Marlie without sale to Josephine: \(r=\dfrac{\$ 10,972.96}{(\$ 489,027.04)\left(\dfrac{364}{365}\right)}=2.25 \%\)

When Marlie sold the T-bill after holding it for 217 days, he realized a 2.50% rate of return. Josephine then held the T-bill for another 148 days to maturity, realizing a 1.85% rate of return. If Marlie hadn't sold the note to Josephine and instead held it for the entire 364 days, he would have realized a 2.25% rate of return.

Step 4:

The yield on the date of issue was 2.25%. Marlie realized a higher rate of return because the interest rates in the market decreased during the 217 days he held it (to 1.85%, which is what Josephine is able to obtain by holding it until maturity). This raises the selling price of the T-bill. If his investment of $489,027.04 grows by 2.25% for 217 days, he has $6,541.57 in interest. The additional $733.60 of interest (totaling $7,275.17) is due to the lower yield in the market, increasing his rate of return to 2.50% instead of 2.25%.