19.1.3: Unit Circle Trigonometry

- Page ID

- 70068

- Understand unit circle, reference angle, terminal side, standard position.

- Find the exact trigonometric function values for angles that measure \(30^{\circ}\), \(45^{\circ}\), and \(60^{\circ}\) using the unit circle.

- Find the exact trigonometric function values of any angle whose reference angle measures \(30^{\circ}\), \(45^{\circ}\), or \(60^{\circ}\).

- Determine the quadrants where sine, cosine, and tangent are positive and negative.

Introduction

Mathematicians create definitions because they have a use in solving certain kinds of problems. For example, the six trigonometric functions were originally defined in terms of right triangles because that was useful in solving real-world problems that involved right triangles, such as finding angles of elevation. The domain, or set of input values, of these functions is the set of angles between \(0^{\circ}\) and \(90^{\circ}\). You will now learn new definitions for these functions in which the domain is the set of all angles. The new functions will have the same values as the original functions when the input is an acute angle. In a right triangle you can only have acute angles, but you will see the definition extended to include other angles.

One use for these new functions is that they can be used to find unknown side lengths and angle measures in any kind of triangle. These new functions can be used in many situations that have nothing to do with triangles at all.

Before looking at the new definitions, you need to become familiar with the standard way that mathematicians draw and label angles.

General Angles

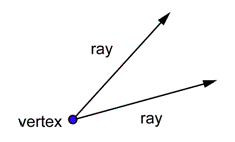

From geometry, you know that an angle is formed by two rays. The rays meet at a point called a vertex.

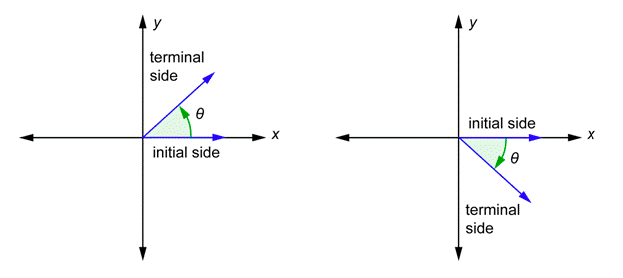

In trigonometry, angles are placed on coordinate axes. The vertex is always placed at the origin and one ray is always placed on the positive \(x\)-axis. This ray is called the initial side of the angle. The other ray is called the terminal side of the angle. This positioning of an angle is called standard position. The Greek letter theta (\(\theta\)) is often used to represent an angle measure. Two angles in standard position are shown below.

When an angle is drawn in standard position, it has a direction. There are little curved arrows in the above drawing. The one on the left goes counterclockwise and is defined to be a positive angle. The one on the right goes clockwise and is defined to be a negative angle. If you used a protractor to measure the angles, you would get \(50^{\circ}\) in both cases. We refer to the first one as a \(50^{\circ}\) angle, and we refer to the second one as a \(-50^{\circ}\) angle.

Why would you even have negative angles? As with all definitions, it is a matter of convenience. A spaceship in a circular orbit around Earth’s equator could be traveling in either of two directions. So you could say that it traveled through a \(-50^{\circ}\) angle to indicate that it went in the opposite direction of a spaceship that went through a \(50^{\circ}\) angle. Why is counterclockwise positive? This is just a convention, something that mathematicians have agreed on, because one way has to be positive and the other way negative.

Supplemental Interactive Activity

To understand how positive angles result from counterclockwise rotation and negative angles result from clockwise rotation, try the interactive exercise below. Either enter an angle measure in the box labeled Angle and hit enter or use the slider to move the terminal side of angle \(\theta\) through the quadrants.

*Insert Interactive Activity

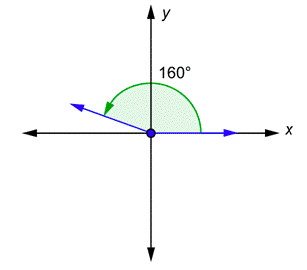

Problem: Draw a \(160^{\circ}\) angle in standard position.

Answer

The angle is positive, so you start at the \(x\)-axis and go \(160^{\circ}\) counterclockwise.

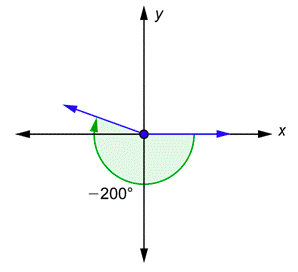

Problem: Draw a \(-200^{\circ}\) angle in standard position.

Answer

The angle is negative, so you start at the \(x\)-axis and go \(200^{\circ}\) clockwise. Remember that \(180^{\circ}\) is a straight line. That will bring you to the negative \(x\)-axis, and then you have to go \(20^{\circ}\) farther.

Notice that the terminal sides in the two examples above are the same, but they represent different angles. Such pairs of angles are said to be coterminal angles.

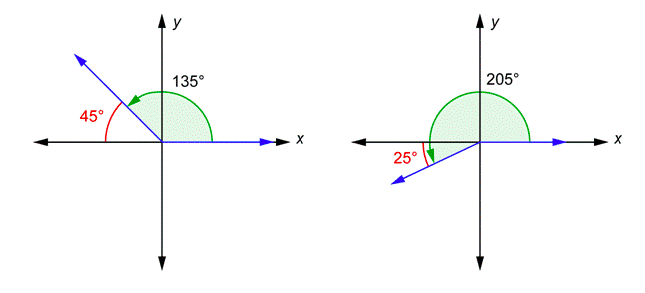

For each angle drawn in standard position, there is a related angle known as a reference angle. This is the angle formed by the terminal side and the \(x\)-axis. The reference angle is always considered to be positive, and has a value anywhere from \(0^{\circ}\) to \(90^{\circ}\). Two angles are shown below in standard position.

You can see that the terminal side of the \(135^{\circ}\) angle and the \(x\)-axis form a \(45^{\circ}\) angle (this is because the two angles must add up to \(180^{\circ}\)). This \(45^{\circ}\) angle, shown in red, is the reference angle for \(135^{\circ}\). The terminal side of the \(205^{\circ}\) angle and the \(x\)-axis form a \(25^{\circ}\) angle. It is \(25^{\circ}\) because \(205^{\circ} = 180^{\circ} + 25^{\circ}\). This \(25^{\circ}\) angle, shown in red, is the reference angle for \(205^{\circ}\).

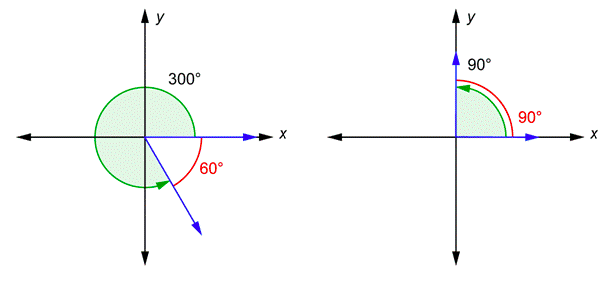

Here are two more angles in standard position.

The terminal side of the \(300^{\circ}\) angle and the \(x\)-axis form a \(60^{\circ}\) angle (this is because the two angles must add up to \(360^{\circ}\)). This \(60^{\circ}\) angle, shown in red, is the reference angle for \(300^{\circ}\). The terminal side of the \(90^{\circ}\) angle and the \(x\)-axis form a \(90^{\circ}\) angle. The reference angle is the same as the original angle in this case. In fact, any angle from \(0^{\circ}\) to \(90^{\circ}\) is the same as its reference angle.

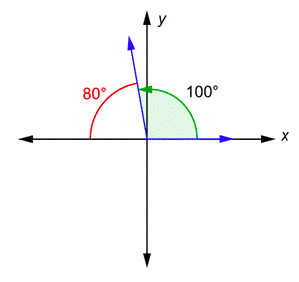

Problem: What is the reference angle for \(100^{\circ}\)?

Answer

The terminal side is in Quadrant II. The original angle and the reference angle together form a straight line along the \(x\)-axis, so their sum is \(180^{\circ}\).

Therefore, the reference angle is \(80^{\circ}\).

The reference angle for \(180^{\circ}\) is \(80^{\circ}\).

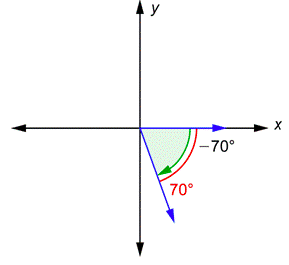

Problem: What is the reference angle for \(-70^{\circ}\)?

Answer

The terminal side and the \(x\)-axis form the “same” angle as the original. A reference angle is always a positive number, so the reference angle here is \(70^{\circ}\), shown in red.

The reference angle for \(-70^{\circ}\) is \(70^{\circ}\).

What is the reference angle for \(310^{\circ}\)?

- \(40^{\circ}\)

- \(50^{\circ}\)

- \(-40^{\circ}\)

- \(-50^{\circ}\)

- Answer

-

- \(40^{\circ}\). Incorrect. You may have correctly drawn the angle in standard position, turning counterclockwise and landing in the fourth quadrant. However, you may have looked at the angle formed by the terminal side and the \(y\)-axis, instead of the \(x\)-axis. The correct answer is \(50^{\circ}\).

- \(50^{\circ}\). Correct. In standard position, the angle will turn counterclockwise through the first, second, third, and into the fourth quadrant. The reference angle and the original angle together make one full circle, or \(360^{\circ}\). Therefore, the reference angle is \(360^{\circ}-310^{\circ}=50^{\circ}\).

- \(-40^{\circ}\). Incorrect. You may have correctly drawn the angle in standard position, turning counterclockwise and landing in the fourth quadrant. However, you may have looked at the angle formed by the terminal side and the \(y\)-axis, instead of the \(x\)-axis. Also, the reference angle is always positive. The correct answer is \(50^{\circ}\).

- \(-50^{\circ}\). Incorrect. You may have correctly drawn the angle in standard position, turning counterclockwise and landing in the fourth quadrant. However, you may have confused the reference angle with a coterminal angle. Remember that the reference angle is always positive. The correct answer is \(50^{\circ}\).

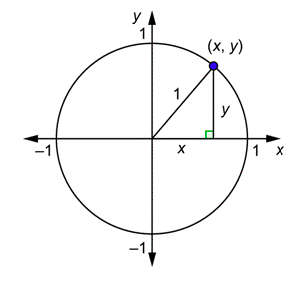

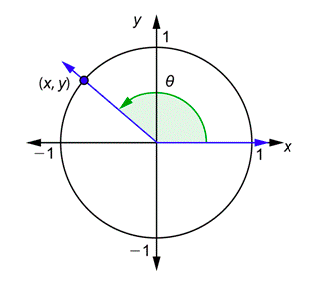

A unit circle is a circle that is centered at the origin and has radius 1, as shown below.

If \((x,y)\) are the coordinates of a point on the circle, then you can see from the right triangle in the drawing and the Pythagorean Theorem that \(x^2 + y^2 = 1\). This is the equation of the unit circle.

The General Definition of the Trigonometric Functions

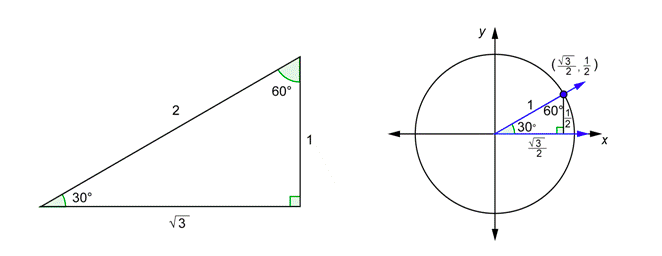

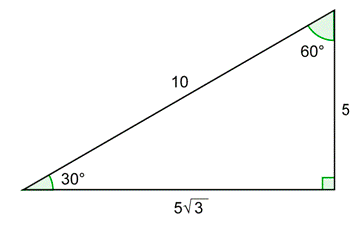

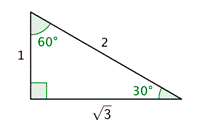

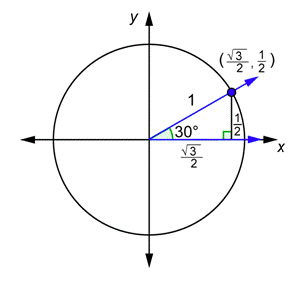

The \(30^{\circ}\) - \(60^{\circ}\) - \(90^{\circ}\) triangle is seen below on the left. Next to that is a \(30^{\circ}\) angle drawn in standard position together with a unit circle.

The two triangles have the same angles, so they are similar. Therefore, corresponding sides are proportional. The hypotenuse on the right has length 1 (because it is a radius). Since this is half of the hypotenuse on the left, all of the sides on the right are half of the corresponding sides on the left. For example, the side adjacent to the \(30^{\circ}\) angle on the left is \(\sqrt{3}\); therefore the corresponding side on the triangle on the right has to be half that, or \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\).

Look at the right triangle on the left. Using the definitions of sine and cosine:

\(\cos 30^{\circ}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \text { and } \sin 30^{\circ}=\frac{1}{2}\)

Now look at the point where the terminal side intersects the unit circle. The \(x\)-coordinate is equal to \(\cos 30^{\circ}\), and the \(y\)-coordinate is equal to \(\sin 30^{\circ}\). This is not a coincidence. Let’s look at a more general case.

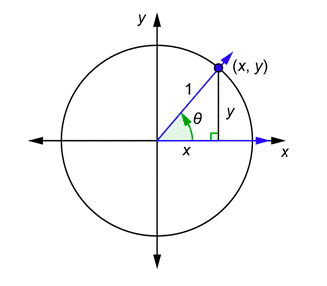

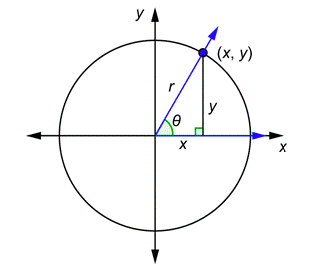

Suppose you draw any acute angle \(\theta\) in standard position together with a unit circle, as seen below.

The terminal side of the angle intersects the unit circle at the point \((x,y)\). Let’s write the definitions of the six trigonometric functions and then rewrite them by referring to the triangle above and using the variables \(x\) and \(y\).

\(\begin{array}{cc}

\sin \theta=\frac{\text { opposite }}{\text { hypotenuse }}=\frac{y}{1}=y & \csc \theta=\frac{\text { hypotenuse }}{\text { opposite }}=\frac{1}{y} \\

\cos \theta=\frac{\text { adjacent }}{\text { hypotenuse }}=\frac{x}{1}=x & \sec \theta=\frac{\text { hypotenuse }}{\text { adjacent }}=\frac{1}{x} \\

\tan \theta=\frac{\text { opposite }}{\text { adjacent }}=\frac{y}{x} & \cot \theta=\frac{\text { adjacent }}{\text { opposite }}=\frac{x}{y}

\end{array}\)

The first equation and the one below it, with the middle steps cut out, tell you:

\(\sin \theta=y \text { and } \cos \theta=x\)

Now you can see that the \(y\)-coordinate of this point is always equal to the sine of the angle, and the \(x\)-coordinate of this point is always equal to the cosine of the angle.

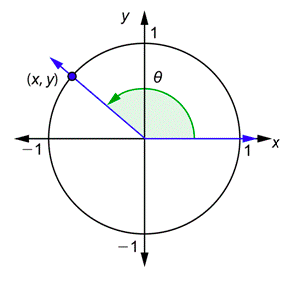

Now consider any angle \(\theta\) in standard position together with a unit circle. The terminal side will intersect the circle at some point \((x,y)\). Depending on the angle, that point could be in the first, second, third, or fourth quadrant.

The sine of the angle \(\theta\) is equal to the \(y\)-coordinate of this point and the cosine of the angle \(\theta\) is equal to the \(x\)-coordinate of this point. In fact, the six trigonometric functions for any angle \(\theta\) are now defined by the six equations listed above.

The next few examples will help you confirm that when \(\theta\) is an acute angle, these new definitions give you the same results as the original definitions.

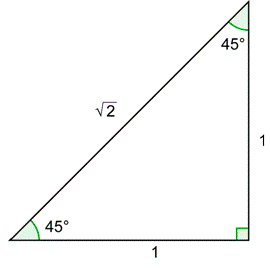

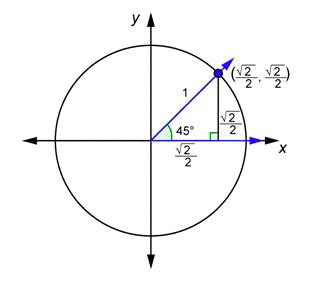

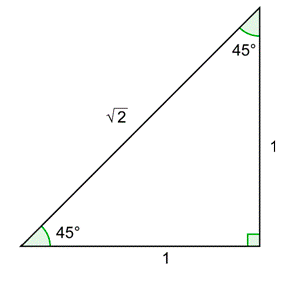

Problem: Draw a \(45^{\circ}\) angle in standard position together with a unit circle. Confirm that the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates of the point of intersection of the terminal side and the circle are equal to \(\cos 45^{\circ}\) and \(\sin 45^{\circ}\).

Answer

Start with the \(45^{\circ}\) - \(45^{\circ}\) - \(90^{\circ}\) triangle. Then draw the \(45^{\circ}\) angle in standard position.

This unit circle triangle is similar to the \(45^{\circ}\) - \(45^{\circ}\) - \(90^{\circ}\) triangle. Each side length can be obtained by dividing the lengths of the \(45^{\circ}\) - \(45^{\circ}\) - \(90^{\circ}\) triangle by \(\sqrt{2}\). So each leg on the unit circle triangle is: \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\)

Look at the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates of the point on the unit circle, then use the triangle to find \(\cos 45^{\circ}\) and \(\sin 45^{\circ}\).

\(\begin{array}{l}

\text { From the coordinates on the }\\

\text { unit circle: } x=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}

\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}

\text { From the triangle: }\\

\cos 45^{\circ}=\frac{\text { adjacent }}{\text { hypotenuse }}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}

\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}

\text { From the coordinates on the }\\

\text { unit circle: } y=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}

\end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l}

\text { From the triangle: }\\

\sin 45^{\circ}=\frac{\text { opposite }}{\text { hypotenuse }}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}

\end{array}\)

The \(x\)-coordinate is equal to \(\cos 45^{\circ}\), and the \(y\)-coordinate is equal to \(\sin 45^{\circ}\).

\(\text { Yes, } x=\cos 45^{\circ} \text { and } y=\sin 45^{\circ} \text { . }\)

In the next two examples, the angle labels of \(37^{\circ}\) and \(53^{\circ}\) are actually very close approximations. The main idea of the examples (that those fractions involving \(x\) and \(y\) are equal to the various trigonometric functions) still holds true.

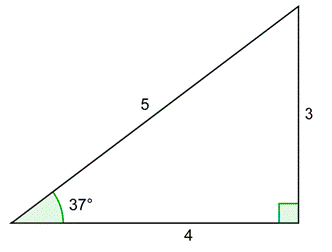

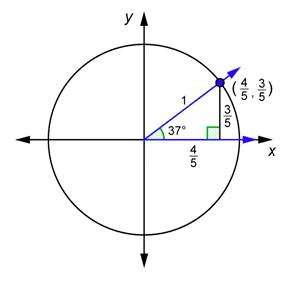

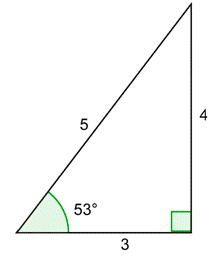

Problem: Draw a \(37^{\circ}\) angle in standard position together with a unit circle. Use the triangle below to find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates of the point of intersection of the terminal side and the circle. Compute \(\frac{y}{x}\) and \(\frac{x}{y}\). Confirm that they are equal to \(\tan 37^{\circ}\) and \(\cot 37^{\circ}\).

Answer

Draw the \(37^{\circ}\) angle in standard position. The unit circle triangle is similar to the 3 - 4 - 5 right triangle. Because this hypotenuse equals the original hypotenuse divided by 5, you can find the leg lengths by dividing the original leg lengths by 5.

Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates.

\(x=\frac{4}{5}, y=\frac{3}{5}\)

Compute the ratios. Compare the results to what you would get for \(\tan 37^{\circ}\) and \(\cot 37^{\circ}\) using the original triangle. They are the same!

\(\begin{array}{l}

\frac{y}{x}=\frac{\frac{3}{5}}{\frac{4}{5}}=\frac{3}{5} \cdot \frac{5}{4}=\frac{3}{4} \\

\tan 37^{\circ}=\frac{\text { opposite }}{\text { adjacent }}=\frac{3}{4} \\

\frac{x}{y}=\frac{\frac{4}{5}}{\frac{3}{5}}=\frac{4}{5} \cdot \frac{5}{3}=\frac{4}{3} \\

\cot 37^{\circ}=\frac{\text { adjacent }}{\text { opposite }}=\frac{4}{3}

\end{array}\)

\(\text { So yes, } \frac{y}{x}=\tan 37^{\circ} \text { and } \frac{x}{y}=\cot 37^{\circ}\)

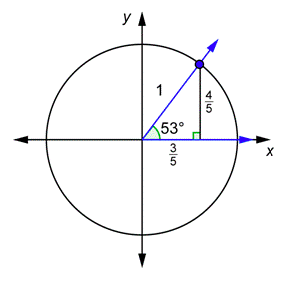

Problem: Draw a \(53^{\circ}\) angle in standard position together with a unit circle. Use the triangle below to find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates of the point of intersection of the terminal side and the circle. Compute \(\frac{1}{x}\) and \(\frac{1}{y}\). Confirm that they are equal to \(\sec 53^{\circ}\) and \(\csc 53^{\circ}\).

Answer

Draw the \(53^{\circ}\) angle in standard position. The unit circle triangle is similar to the 3 - 4 - 5 right triangle. Because this hypotenuse equals the original hypotenuse divided by 5, you can find the leg lengths by dividing the original leg lengths by 5.

Find the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates.

\(x=\frac{3}{5}, y=\frac{4}{5}\)

Compute the ratios. Compare the results to what you would get for \(\sec 53^{\circ}\) and \(\csc 53^{\circ}\) using the original triangle. They are the same!

\(\text { Yes, } \frac{1}{x}=\sec 53^{\circ} \text { and } \frac{1}{y}=\csc 53^{\circ}\)

The first three of our new definitions lead us to one more important identity:

\(\sin \theta=y, \cos \theta=x, \tan \theta=\frac{y}{x}\)

We can replace \(y\) by \(\sin \theta\) and \(x\) by \(\cos \theta\) in \(\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x}\) to get the trigonometry identity \(\tan \theta = \frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}\).

\(\tan \theta=\frac{y}{x}=\frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}\)

Since cotangent is the reciprocal of tangent, this gives you another trigonometric identity.

\(\tan \theta=\frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta} \text { and } \cot \theta=\frac{\cos \theta}{\sin \theta}\)

Remember, an identity is true for every possible value of the variable. So no matter what angle you are using, the values of tangent and cotangent are given by these quotients.

Although some textbooks give slightly different general definitions of the trigonometric functions, the important thing to know is that they end up giving you the same values as the definitions already given to you.

For example, start with a circle of radius \(r\) (in place of radius 1) and an angle \(\theta\) in standard position. The terminal side will intersect the circle at some point \((x,y)\). That point could be in any quadrant, but we show one in the first quadrant.

Now write down the original definitions and then rewrite them using the variables \(x\), \(y\), and \(r\).

\(\begin{array}{lr}

\sin \theta=\frac{\text { opposite }}{\text { hypotenuse }}=\frac{y}{r} & \csc \theta=\frac{\text { hypotenuse }}{\text { opposite }}=\frac{r}{y} \\

\cos \theta=\frac{\text { adjacent }}{\text { hypotenuse }}=\frac{x}{r} & \sec \theta=\frac{\text { hypotenuse }}{\text { adjacent }}=\frac{r}{x} \\

\tan \theta=\frac{\text { opposite }}{\text { adjacent }}=\frac{y}{x} & \cot \theta=\frac{\text { adjacent }}{\text { opposite }}=\frac{x}{y}

\end{array}\)

These six fractions are used as the general definitions of the trigonometric functions for any angle \(\theta\), in any quadrant.

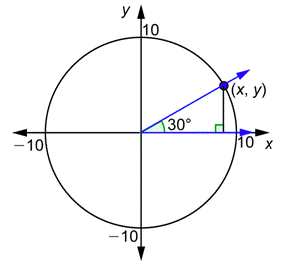

Problem: Compute \(\frac{y}{x}\) using the diagram below. Confirm that this is the same as the value of \(\tan 30^{\circ}\).

Answer

The above diagram contains a \(30^{\circ}\) - \(60^{\circ}\) - \(90^{\circ}\) triangle.

The hypotenuse equals the radius, so it is 10. The side opposite \(30^{\circ}\) is half of 10, or 5. The adjacent side is \(\sqrt{3}\) times the opposite side, or \(5\sqrt{3}\).

The sides of the triangle give you the values of \(x\) and \(y\) in the first diagram.

\(\begin{array}{c}

y=5 \\

x=5 \sqrt{3}

\end{array}\)

Substitute these into the definition.

\(\tan \theta=\frac{y}{x}=\frac{5}{5 \sqrt{3}}=\frac{5}{5 \sqrt{3}} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{3}}=\frac{5 \sqrt{3}}{5 \cdot 3}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}\)

Here is our standard \(30^{\circ}\) - \(60^{\circ}\) - \(90^{\circ}\) triangle.

Compute \(\tan 30^{\circ}\) using the right triangle definition.

\tan 30^{\circ}=\frac{\text { opposite }}{\text { adjacent }}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{3}}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}

\(\text { So yes, } \frac{y}{x}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}=\tan 30^{\circ}\)

Using the General Definitions of the Trigonometric Functions

You have been given new or “general” definitions of the six trigonometric functions and have seen that, when you compute these functions using acute angles, the result is the same as the result you would get from using the original definitions. Now you will learn how to apply these definitions to angles that are not acute and to negative angles.

Given any angle \(\theta\), draw it in standard position together with a unit circle. The terminal side will intersect the circle at some point (\(x,y\)), as shown below.

Here again are the general definitions of the six trigonometric functions using a unit circle.

| \(\sin \theta = y\) | \(\csc \theta = \frac{1}{y}\) |

| \(\cos \theta = x\) | \(\sec \theta = \frac{1}{x}\) |

| \(\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x}\) | \(\cot \theta = \frac{x}{y}\) |

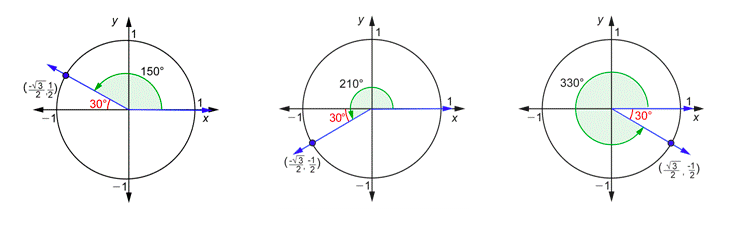

Now let’s use these definitions with the angles \(30^{\circ}\), \(150^{\circ}\), \(210^{\circ}\), and \(330^{\circ}\). You have already done this for \(30^{\circ}\). Here is that drawing:

The angles \(150^{\circ}\), \(210^{\circ}\), and \(330^{\circ}\) have something in common. Every one of them has a reference angle of \(30^{\circ}\), as you can see from the drawings below. Because of this, it is easy to find the coordinates of the points where the terminal sides intersect the unit circle using the drawing above.

- For the angle \(150^{\circ}\), this intersection point is the mirror image of \(\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\right)\) over the \(y\)-axis, so the coordinates for \(150^{\circ}\) are \(\left(\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\right)\).

- For the angle \(210^{\circ}\), this point is the mirror image of \(\left(\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\right)\) over the \(x\)-axis, so the coordinates for \(210^{\circ}\) are \(\left(\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}, -\frac{1}{2}\right)\).

- For the angle \(330^{\circ}\), this point is the mirror image of \(\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\right)\) over the \(x\)-axis, so the coordinates for \(330^{\circ}\) are \(\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, -\frac{1}{2}\right)\).

You can now find the values of all six trigonometric functions for \(150^{\circ}\), \(210^{\circ}\), and \(330^{\circ}\). Let’s pick a few trigonometric functions and evaluate them using these angles. For example, using the leftmost diagram above and the definition of cosine:

\(\begin{aligned}

\cos \theta &=x \\

\cos 150^{\circ} &=\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}

\end{aligned}\)

Using the middle diagram and the definition of cotangent:

\(\begin{array}{c}

\cot \theta=\frac{x}{y} \\

\cot 210^{\circ}=\frac{\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}}{-\frac{1}{2}}=\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2} \cdot \frac{2}{-1}=\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{-1}=\sqrt{3}

\end{array}\)

Using the rightmost diagram and the definition of cosecant:

\(\begin{array}{c}

\csc \theta=\frac{1}{y} \\

\csc 330^{\circ}=\frac{1}{-\frac{1}{2}}=-2

\end{array}\)

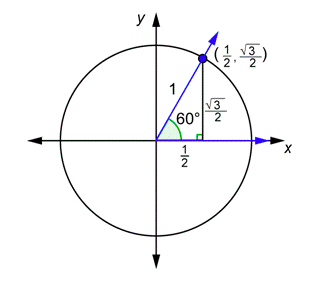

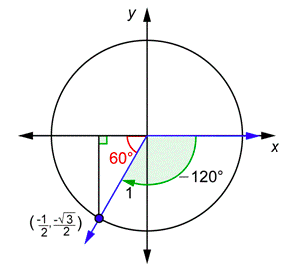

If you take the drawing above with the \(30^{\circ}\) angle in standard position, and turn the triangle so that the shorter leg is on the \(x\)-axis, you get a drawing of a \(60^{\circ}\) angle in standard position, as seen below.

You can use the information in this diagram to find the values of the six trigonometric functions for any angle that has a reference angle of \(60^{\circ}\).

Problem: Determine \(\cos (300^{\circ})\) and \(\sec (300^{\circ})\).

Answer

Draw \(300^{\circ}\) in standard position and find the reference angle. Find the \(x\)-coordinate of the point (\(x,y\)) where the terminal side intersects the unit circle. Because \(\cos 60^{\circ}=\frac{1}{2}\), we know \(x = \frac{1}{2}\).

Use the definition of cosine. Substitute the value of the \(x\)-coordinate that you found above.

\(\begin{array}{c}

\cos \theta=x \\

\cos 300^{\circ}=\frac{1}{2}

\end{array}\)

Use the definition of secant. Substitute the value of the \(x\)-coordinate that you found above. Note that, just as with acute angles, secant and cosine are reciprocals.

\(\begin{array}{c}

\sec \theta=\frac{1}{x} \\

\sec 300^{\circ}=\frac{1}{\frac{1}{2}}=2

\end{array}\)

\(\cos 300^{\circ}=\frac{1}{2}, \sec 300^{\circ}=2\)

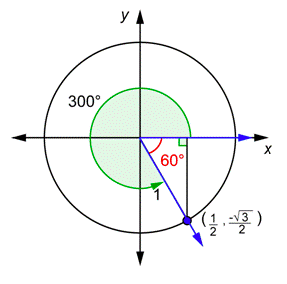

The procedure is the same even if the angle is negative. Remember that a negative angle is simply one whose direction is clockwise.

Problem: Find the values of \(\sin (-120^{\circ})\) and \(\csc (-120^{\circ})\).

Answer

Draw \(-120^{\circ}\) in standard position and find the reference angle. Find the \(y\)-coordinate of the point (\(x,y\)) where the terminal side intersects the unit circle.

Because \(\sin 60^{\circ}=\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) and we are in the third quadrant, we know \(y=-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\).

Use the definition of sine. Substitute the value of the \(y\)-coordinate that you found above.

\(\begin{array}{c}

\sin \theta=y \\

\sin \left(-120^{\circ}\right)=-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}

\end{array}\)

Use the definition of cosecant. Substitute the value of the \(y\)-coordinate that you found above. Rationalize the denominator. Note that, just as with acute angles, cosecant and sine are reciprocals.

\(\begin{aligned}

\csc \theta &=\frac{1}{y} \\

\csc \left(-120^{\circ}\right)=\frac{1}{\frac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}} &=-\frac{2}{\sqrt{3}} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{3}}{\sqrt{3}}=-\frac{2 \sqrt{3}}{3}

\end{aligned}\)

\(\sin \left(-120^{\circ}\right)=-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, \csc \left(-120^{\circ}\right)=-\frac{2 \sqrt{3}}{3}\)

Look at the results from the last two examples and observe the following:

In each case, the value of the trigonometric function was either the same as the value of that function for the reference angle (\(60^{\circ}\)), or the negative of the value of that function for the reference angle. Why did this happen? The computations for \(60^{\circ}\) were done using the point \(\left(\frac{1}{2}, \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\). The computations for \(300^{\circ}\) and \(-120^{\circ}\) were done using the points \(\left(\frac{1}{2}, -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\) and \(\left(-\frac{1}{2}, -\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)\). The \(x\)-coordinates have the same absolute value. The \(y\)-coordinates also have the same absolute value. When you substitute into the expressions \(x, \frac{1}{x}, y,\) and \(\frac{1}{y}\), the result will be the same, or have a negative sign.

You will get a similar result with other angles. So the procedure for finding the value of a trigonometric function simplifies to the following:

- Determine the reference angle.

- Calculate the trigonometric function value of the reference angle.

- Determine if the value of the function is positive or negative.

Let’s try this procedure in the following example.

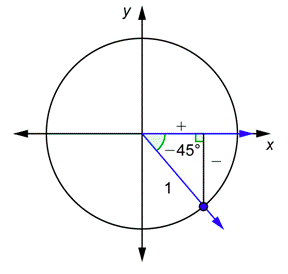

Problem: Compute \(\tan (-45^{\circ})\) and \(\cot (-45^{\circ})\).

Answer

Draw the angle in standard position. The reference angle is \(45^{\circ}\).

Use the \(45^{\circ}\) - \(45^{\circ}\) - \(90^{\circ}\) triangle. The value of \(\tan 45^{\circ}\) is 1.

In the first diagram, we put a + sign to indicate that \(x\) is positive, and a - sign to indicate that \(y\) is negative. Use this to determine the sign of \(\tan (-45^{\circ})\).

\(\tan \left(-45^{\circ}\right)=\frac{y}{x}=\frac{(-)}{(+)}=(-)\)

Since the result was negative, the value of \(\tan (-45^{\circ})\) is negative.

\(\tan \left(-45^{\circ}\right)=-\tan 45^{\circ}=-1\)

You can go through a similar procedure with cotangent or use the fact that it is the reciprocal of tangent.

\(\cot \left(-45^{\circ}\right)=\frac{1}{\tan \left(-45^{\circ}\right)}=\frac{1}{-1}=-1\)

\(\begin{array}{l}

\tan \left(-45^{\circ}\right)=-1 \\

\cot \left(-45^{\circ}\right)=-1

\end{array}\)

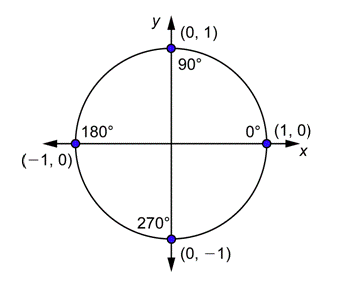

The angles whose measures are a multiple of \(90^{\circ}\) have terminal sides on the axes. This can be confusing, because the terminal side is not in one quadrant, but rather on a border between quadrants. So let’s look at these angles separately. The drawing below shows the points of intersection of the terminal sides of \(0^{\circ}\), \(90^{\circ}\), \(180^{\circ}\), and \(270^{\circ}\) with the unit circle.

You can use this drawing and the definitions to find the trigonometric functions for (0^{\circ}\), \(90^{\circ}\), \(180^{\circ}\), and \(270^{\circ}\). For example:

\(\begin{array}{c}

\sin \theta=y \\

\sin 0^{\circ}=0 \\

\sin 90^{\circ}=1 \\

\sin 180^{\circ}=0 \\

\sin 270^{\circ}=-1

\end{array}\)

For all six functions, you substitute the values of \(x\) and \(y\) as you did earlier. However, what happens if you try to compute \(\tan 90^{\circ}\) using the definition \(\tan \theta=\frac{y}{x}\)?

\(\begin{array}{c}

\tan \theta=\frac{y}{x} \\

\tan 90^{\circ}=? \frac{1}{0}

\end{array}\)

You cannot divide by 0, so \(\tan 90^{\circ}\) is simply undefined. Similarly, \(\csc 180^{\circ}\) is undefined, because if you try to apply the definition, you will end up dividing by 0. The same is true any time one of the definitions leads to division by 0: the trigonometric function is undefined for that angle.

What are the values of \(\cos 90^{\circ}\) and \(\cot 180^{\circ}\)?

- \(\cos 90^{\circ}=0 \text { and } \cot 180^{\circ}=0\)

- \(\cos 90^{\circ}=0 \text { and } \cot 180^{\circ}=\text { undefined }\)

- \(\cos 90^{\circ}=1 \text { and } \cot 180^{\circ}=0\)

- \(\cos 90^{\circ}=1 \text { and } \cot 180^{\circ}=\text { undefined }\)

- Answer

-

- \(\cos 90^{\circ}=0 \text { and } \cot 180^{\circ}=0\). Incorrect. The value for cosine is correct. However, when evaluating cotangent, you may have switched the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates. The correct answer is B.

- \(\cos 90^{\circ}=0 \text { and } \cot 180^{\circ}=\text { undefined }\). Correct. Since \(\cos \theta = x\) and \(90^{\circ}\) corresponds to the point (0,1), \(\cos 90 = 0\). Now \(\cot \theta=\frac{x}{y}\) and \(180^{\circ}\) corresponds to the point (-1,0). If you tried to apply the definition you would be dividing by 0, because \(y = 0\). This means that \(\cot 180^{\circ}\) is undefined.

- \(\cos 90^{\circ}=1 \text { and } \cot 180^{\circ}=0\). Incorrect. When evaluating both of these functions, you may have switched the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates. The correct answer is B.

- \(\cos 90^{\circ}=1 \text { and } \cot 180^{\circ}=\text { undefined }\). Incorrect. The value for cotangent is correct. However, when evaluating cosine, you may have switched the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates. The correct answer is B.

You can use the following charts to help you remember the values of the trigonometric functions for the reference angles \(0^{\circ}\), \(30^{\circ}\), \(45^{\circ}\), \(60^{\circ}\), and \(90^{\circ}\) for sine and cosine. Once you have these, you can get the value of tangent from the identity \(\tan \theta=\frac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}\), and the values of the other three trigonometric functions using reciprocals.

Make a table as follows:

| \(0^{\circ}\) | \(30^{\circ}\) | \(45^{\circ}\) | \(60^{\circ}\) | \(90^{\circ}\) | |

| sine | |||||

| cosine |

As an initial step, put the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 in the “sine” row and 4, 3, 2, 1, and 0 in the “cosine” row. Do this in pencil. You are going to replace these numbers!

| \(0^{\circ}\) | \(30^{\circ}\) | \(45^{\circ}\) | \(60^{\circ}\) | \(90^{\circ}\) | |

| sine | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| cosine | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Now replace the numbers 0 through 4 by taking their square roots and dividing by 2. The rows now contain the correct, but unsimplified, values for sine and cosine.

| \(0^{\circ}\) | \(30^{\circ}\) | \(45^{\circ}\) | \(60^{\circ}\) | \(90^{\circ}\) | |

| sine | \(\frac{\sqrt{0}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{1}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{4}}{2}\) |

| cosine | \(\frac{\sqrt{4}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{1}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{0}}{2}\) |

You can simplify \(\sqrt{0}\) to 0, \(\sqrt{1}\) to 1, and \(\sqrt{4}\) to 2, and then divide by 2. This will give you the final table with the correct values of sine and cosine at these angles.

| \(0^{\circ}\) | \(30^{\circ}\) | \(45^{\circ}\) | \(60^{\circ}\) | \(90^{\circ}\) | |

| sine | 0 | \(\frac{1}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) | 1 |

| cosine | 1 | \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) | \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) | \(\frac{1}{2}\) | 0 |

Determining the Sign of the Trigonometric Functions

First you learned the definitions for the trigonometric functions of an acute angle. Then you learned the general definitions of these functions, which can be used for any angle, and the method for applying them. Finally, you learned a simpler procedure for finding the values of trigonometric functions:

- Determine the reference angle.

- Calculate the trigonometric function value of the reference angle.

- Determine if the value of the function is positive or negative.

Now you’ll learn an easy way to remember where the trigonometric functions are positive and where they are negative.

The sine function: since \(\sin \theta = y\), sine is positive when \(y > 0\). This occurs in Quadrants I and II.

The cosine function: since \(\cos \theta = x\), cosine is positive when \(x > 0\). This occurs in Quadrants I and IV.

The tangent function: since \(\tan \theta=\frac{y}{x}\), tangent is positive when \(x\) and \(y\) are both positive or both negative. This occurs in Quadrants I and III.

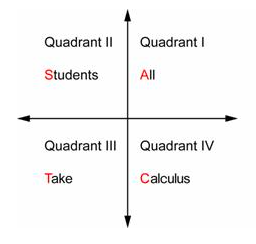

We can summarize this information by quadrant:

Quadrant I: sine, cosine, and tangent are positive.

Quadrant II: sine is positive (cosine and tangent are negative).

Quadrant III: tangent is positive (sine and cosine are negative).

Quadrant IV: cosine is positive (sine and tangent are negative).

Let A stand for all (three functions, sine, cosine, and tangent), S stand for sine, T stand for tangent, and C stand for cosine. Now you can use these single letters to remember in which quadrant sine, cosine, and tangent are positive. The final step is to replace each letter by a word to give you a phrase that’s easy to remember: “All Students Take Calculus.” Going counterclockwise, place these words in the four quadrants.

Now if you look in Quadrant II, for example, you see the word Students. The S tells you that sine is positive (while cosine and tangent are negative).

Problem: What signs are \(\tan 200^{\circ}\) and \(\cos 200^{\circ}\)?

Answer

Since \(200^{\circ} = 180^{\circ} + 20^{\circ}\), is in Quadrant III.

The word “Take” represents the fact that tangent is positive, so \(\tan 200^{\circ}\) is positive.

Sine and cosine are negative in Quadrant III, so \(\cos 200^{\circ}\) is negative.

\(\begin{array}{l}

\tan 200^{\circ} \text { is positive and }\\

\cos 200^{\circ} \text { is negative. }

\end{array}\)

Problem: In which quadrant must an angle lie if its sine is positive and its tangent is negative?

Answer

The words “All” and “Students” tell us that sine is positive in Quadrants I and II.

Tangent is positive in Quadrant I, but negative in Quadrant II.

Quadrant II

This device applies to the functions sine, cosine, and tangent. The other three trigonometric functions are reciprocals of these three. Recall the basic fact that the reciprocal of a positive number is positive, and the reciprocal of a negative number is negative. This implies that sine and cosecant have the same sign, cosine and secant have the same sign, and tangent and cotangent have the same sign. So if you want to know the sign of cosecant, secant, or cotangent, find the sign of sine, cosine, or tangent, respectively.

What signs are \(\cos (-25^{\circ})\) and \(\sec (-25^{\circ})\)?

- They are both positive.

- They are both negative.

- \(\cos (-25^{\circ})\) > 0 and \(\sec (-25^{\circ})\) < 0

- \(\cos (-25^{\circ})\) < 0 and \(\sec (-25^{\circ})\) > 0

- Answer

-

- They are both positive. Correct. Angle \(-25^{\circ}\) is in Quadrant IV. The word “Calculus” tells you that cosine is positive. Since secant is the reciprocal of cosine, it is also positive.

- They are both negative. Incorrect. Perhaps you thought that because the angle is negative, the values of these functions would be negative. The values depend on the quadrant in which the angle lies. Angle \(-25^{\circ}\) lies in Quadrant IV. The correct answer is A.

- \(\cos (-25^{\circ})\) > 0 and \(\sec (-25^{\circ})\) < 0. Incorrect. The sign of cosine is correct. Perhaps you thought that when you take a reciprocal, the sign changes, but the sign doesn’t change. Therefore, secant and cosine have the same sign. The correct answer is A.

- \(\cos (-25^{\circ})\) < 0 and \(\sec (-25^{\circ})\) > 0. Incorrect. The sign of secant is correct. Perhaps you thought that because the angle is negative, the value of cosine would be negative. The values depend on the quadrant in which the angle lies. Angle \(-25^{\circ}\) lies in Quadrant IV. The correct answer is A.

Summary

The trigonometric functions were originally defined for acute angles. There are general definitions of these functions, which apply to angles of any size, including negative angles. Values of trigonometric functions are computed by finding the reference angle, determining the value of the trigonometric function of the reference angle, and then determining if the value of the function is positive or negative. A useful way to remember this last step is “All Students Take Calculus.”