5.5: Amplitude and Period of the Sine and Cosine Functions

- Page ID

- 125054

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Amplitude

We have seen how the graphs of both the sine function, \(y={\mathrm{sin} \theta \ }\) and the cosine function \(y={\mathrm{cos} \theta \ }\), oscillate between \(-1\) and \(+1\). That is, the heights oscillate between –1 and 1.

The height from the horizontal axis to the peak (or through) of a sine or cosine function is called the amplitude of the function. Each of the curves \(y=\sin \theta\) and \(y=\cos \theta\) has amplitude 1.

If we were to multiply the sine function \(y={\mathrm{sin} \theta \ }\ \)by \(3\), getting \(y={3\mathrm{sin} \theta \ }\), each of the sine values would be multiplied by 3, making each value 3 times what it was. Each height would be tripled. The amplitude of \(y={3\mathrm{sin} \theta \ }\) is 3.

If we were to multiply the cosine function \(y=\mathrm{cos\ }\theta \ \ \)by \(1/3\), getting \(y={1/3\mathrm{cos} \theta \ }\),each of the cosine values would be multiplied by 1/3 making each value 1/3 of what it was. Each height of \(y=\mathrm{cos}\theta \ \)would be 1/3 of what it was.The amplitude of \(y={1/3\mathrm{cos} \theta \ }\) is 1/3.

The Amplitude of \(y=A\mathrm{sin}\theta\) and \(y=A\mathrm{cos}\theta\)

Suppose \(A\) represents a positive number. Then the amplitude of both \(y=A\mathrm{sin}\theta\) and \(y=A\mathrm{cos}\theta\) is \(A\) and it represents height from the horizontal axis to the peak of the curve.

The amplitude of \(y=5/8\mathrm{sin}\theta\) is 5/8. This means that the peak of the curve is 5/8 of a unit above the horizontal axis.

The amplitude of \(y=3\mathrm{sin}\theta\) is 3. This means that the peak of the curve is 3 units above the horizontal axis.

Period

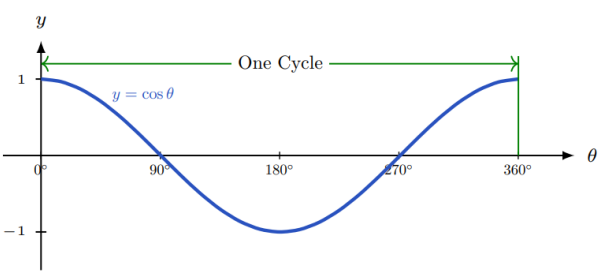

Both the sine function and cosine function, \(y=\mathrm{sin}\theta\) and \(y=\mathrm{cos}\theta ,\) go through exactly one cycle from 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 360\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\).

The period of the sine function and cosine functions, \(y=\mathrm{sin}\theta\) and \(y=\mathrm{cos}\theta ,\) is the “time” required for one complete cycle.

An interesting thing happens to the curves \(y=\mathrm{sin}\theta\) and \(y=\mathrm{cos}\theta\) when the angle \(\theta\) is multiplied by some positive number, \(B.\) If the number \(B\ \)is greater than 1, the number of cycles on 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 360\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) increases for both \(y=\mathrm{sin}\theta\) and \(y=\mathrm{cos}\theta\). That is, the peaks of the curve are closer together, meaning their periods decrease. If the number \(B\ \)is strictly between 0 and 1, the peaks of the curve are farther apart, meaning their periods increase.

The Period of \(y=\mathrm{sin}\left(B\theta \right)\) and \(y=\mathrm{cos}\left(B\theta \right)\)

Suppose \(B\) represents a positive number. Then the period of both \(y=\mathrm{sin}\left(B\theta \right)\) and \(y=\mathrm{cos}\left(\mathrm{B}\theta \right)\) is \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{B}.\) As B gets bigger, \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{B}\) gets smaller and the period increases.

If we were to multiply the angle in the sine function \(y={\mathrm{sin} \theta \ }\ \)by \(3\), getting \(y={\mathrm{sin} 3\theta \ }\), each of the angle’s values would be multiplied by 3 making each value 3 times what it was. Each angle would be tripled and there would be 3 cycles in the interval 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 360\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\).

The period of \(y={\mathrm{sin} 3\theta \ }\) is \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{3}=120{}^\circ\). The period of \(y={\mathrm{sin} 3\theta \ }\) is smaller than that of \(y={\mathrm{sin} \theta \ }\).

If we were to multiply the angle in the sine function \(y={\mathrm{sin} \theta \ }\ \)by \(1/3\), getting \(y=\mathrm{sin}\left(\frac{1}{3}\theta \right).\) Each of the angle’s values would be multiplied by 1/3 making each value 1/3 what it was and there would be only 1/3 of a cycle in the interval 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 360\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\).

The period of \(y=\mathrm{sin}\left(\frac{1}{3}\theta \right)\) is \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{1/3}=\ 360{}^\circ \times \ 3\) = \(1080{}^\circ\). The period of \(y=\mathrm{sin}\left(\frac{1}{3}\theta \right)\) is greater than that of \(y={\mathrm{sin} \theta \ }.\)

Using Technology

We can use technology to help us construct the graph of a sine or cosine function.

Go to www.wolframalpha.com.

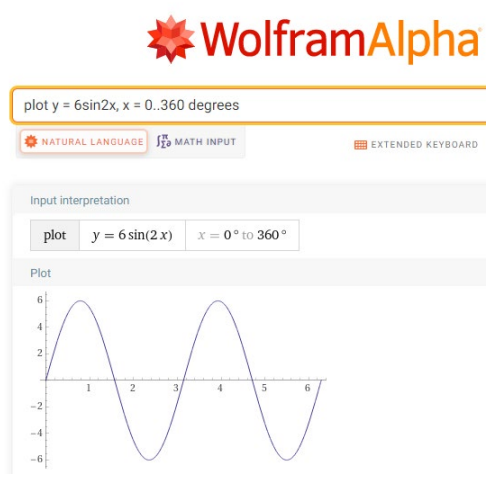

Plot two complete cycles of \(y={\mathrm{6sin} 2\theta \ }\) from 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 360\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\).

Solution

Type plot y = 6sin2x, x = 0..360 degrees in the entry field.

WolframAlpha tells you what it thinks you entered, then produces the graph.

You can see that WolframAlpha has plotted two complete cycles from 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 360\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) with amplitude 6.

Find the period of \(y={\mathrm{6sin} 8\theta \ }\).

Solution

We just need to evaluate \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{B}\) with \(B=8\).

\(\frac{360{}^\circ }{8}=45{}^\circ \)

The period of \(y={\mathrm{6sin} 8\theta \ }\) is \(45{}^\circ\)

The graph of \(y={\mathrm{6sin} 8\theta \ \ }\)helps us visualize this 45\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) period. You can see that the peaks differ by 45\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\).

Try these

Write the equation of each graph.

- Answer

-

- \(y=3\mathrm{sin}\mathrm{}(2x)\)

- \(y=2\mathrm{cos}(3x)\)

- \(y=7\mathrm{cos}\mathrm{}(x)\)

How many complete cycles are there in the graph of \(y=4 \cos (3 \theta)\) from 0° to 360°? What is the period and amplitude of this function?

- Answer

-

3 complete cycles. Period is \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{3}=120{}^\circ .\) Amplitude is 4.

How many complete cycles are there in the graph of \(y=5 \sin \left(\frac{4}{5} \theta\right)\) from 0° to 360°? What is the period and amplitude of this function?

- Answer

-

\(\frac{4}{5}\) of a complete cycle. Period is \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{4/5}=360{}^\circ \times \ \frac{5}{4}=450{}^\circ\). Amplitude is 5.

Write the equation of a sine curve that has amplitude 15 and period 50°. You need to specify both \(A\) and \(B\) in \(y=A \sin (B \theta)\). Keep in mind that the period of this function is \(\frac{360^{\circ}}{B}\).

- Answer

-

\(y=15\mathrm{sin}\left(7.2\theta \right)\), where \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{\ B}=50{}^\circ \to B=\ \frac{360{}^\circ }{\ 50{}^\circ }=7.2\)

Write the equation of a cosine curve that has amplitude 100 and period 12°. You need to specify both \(A\) and \(B\) in \(y=A \cos (B \theta)\). Keep in mind that the period of this function is \(\frac{360^{\circ}}{B}\).

- Answer

-

\(y=100\mathrm{cos}\left(30\theta \right)\), where \(\frac{360{}^\circ }{\ B}=12{}^\circ \to B=\ \frac{360{}^\circ }{\ 12{}^\circ }=30\)

Write the equation of a cosine function that has amplitude 3 and makes two complete cycles from 0° to 180°.

- Answer

-

\(y=3\mathrm{cos}\mathrm{}(4\theta )\) We need to specify both \(A\ \mathrm{and}\ B\) in \(y=A\mathrm{cos}\left(B\theta \right)\). Since the amplitude is 3\(,\ \ A=3.\) Since the curve makes two complete cycles from 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 180\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\), it must make 4 complete cycles from 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 360\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\). So, \(\ B=4.\)

Write the equation of a sine function that has amplitude 4 and makes three complete cycles from 0° to 90°.

- Answer

-

\(y=4\mathrm{sin}\mathrm{}(12\theta )\) We need to specify both \(A\ \mathrm{and}\ B\) in \(y=A\mathrm{cos}\left(B\theta \right)\). Since the amplitude is 4\(,\ \ A=4.\) Since the curve makes three complete cycles from 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 90\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\), it must make 12 complete cycles from 0\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\) to 360\(\mathrm{{}^\circ}\). So, \(B=12\).