1.2: Negative Numbers

- Page ID

- 153106

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Negative numbers are a fact of life, from winter temperatures to our bank accounts. (And occasionally elevators, if they go underground.)

Before we start calculating with negative numbers, we’ll take a look at absolute value. This will make it easier for us to talk about what we’re doing when we add, subtract, multiply, or divide signed numbers.

Absolute Value

The absolute value of a number is its distance from \(0\). You can think of it as the size of a number without identifying it as positive or negative. Numbers with the same absolute value but different signs, such as \(3\) and \(-3\), are called opposites. The absolute value of \(-3\) is \(3\), and the absolute value of \(3\) is also \(3\), because both numbers are \(3\) units away from \(0\).

We use a pair of straight vertical bars to indicate absolute value; for example, \(|-3|=3\) and \(|3|=3\).

Evaluate each expression.

- \(|-5|\)

- \(|5|\)

Adding Negative Numbers

To add two negative numbers, add their absolute values (i.e., ignore the negative signs) and make the final answer negative.

Perform each addition.

- \(–8+(–7)\)

- \(–13+(–9)\)

To add a positive number and a negative number, we subtract the smaller absolute value from the larger. If the positive number has the larger absolute value, the final answer is positive. If the negative number has the larger absolute value, the final answer is negative.

Perform each addition.

- \(7+(–3)\)

- \(–7+3\)

- \(14+(–23)\)

- \(–14+23\)

- The temperature at noon on a chilly Monday was \(–7\)°F. By the next day at noon, the temperature had risen \(25\)°F. What was the temperature at noon on Tuesday?

If an expression consists of only additions, we can break the rules for order of operations and add the numbers in whatever order we choose.

Evaluate each expression using any shortcuts that you notice.

- \(–10+4+(–4)+3+10\)

- \(–291+73+(–9)+27\)

Subtracting Negative Numbers

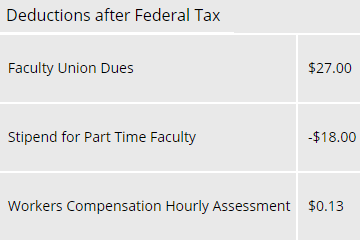

The following image shows part of a paystub in which an \($18\) payment needed to be made, but the payroll folks wanted to track the payment in the deductions category. Of course, a positive number in the deductions will subtract money away from the paycheck. Here, though, a deduction of negative \(18\) dollars has the effect of adding \(18\) dollars to the paycheck. Subtracting a negative amount is equivalent to adding a positive amount.

To subtract two signed numbers, we add the first number to the opposite of the second number.

Perform each subtraction.

- \(5–2\)

- \(2–5\)

- \(–2–5\)

- \(–5–2\)

- \(2–(–5)\)

- \(5–(–2)\)

- \(–2–(–5)\)

- \(–5–(–2)\)

Absolute Value, Revisited

Absolute value can be useful when we want to find the difference between two numbers but we want the result to be positive. For example, suppose that the temperature in Portland, Oregon is \(43\)°F, and the temperature in Portland, Maine is \(–12\)°F. What is the difference in temperature? The simplest way to find the difference is to do \(43–(–12)=43+12=55\), and you would report that as a difference of “fifty-five degrees Fahrenheit”. If you instead did \(–12–43=-55\), it would sound a bit strange to say the the difference is “negative fifty-five degrees Fahrenheit” and you would most likely ignore the negative sign when reporting the difference. To guarantee that the result of a subtraction is positive, we can put absolute value bars around the entire calculation. This is sometimes called the positive difference.

Evaluate each expression.

- \(|-12-43|\)

- \(|43-(-12)|\)

- The lowest point in Colorado is on the Arikaree River, with an elevation \(3,317\) feet above sea level. The highest point in Colorado is the peak of Mount Elbert, with an elevation \(14,440\) feet above sea level.[1] Find the positive difference between these elevations.

- The lowest point in Louisiana is in New Orleans, with an elevation \(8\) feet below sea level. The highest point in Louisiana is the peak of Driskill Mountain, with an elevation \(535\) feet above sea level.[2] Find the positive difference between these elevations.

Multiplying Negative Numbers

Suppose you spend \(3\) dollars on a coffee every day. We could represent spending 3 dollars as a negative number, \(-3\) dollars. Over the course of a \(5\)-day work week, you would spend \(15\) dollars, which we could represent as \(-15\) dollars. This shows that \(-3\cdot5=-15\), or \(5\cdot-3=-15\).

If two numbers with opposite signs are multiplied, the product is negative.

Find each product.

- \(-4\cdot3\)

- \(5(-8)\)

Going back to our coffee example, we saw that \(5(-3)=-15\). Therefore, the opposite of \(5(-3)\) must be positive \(15\). Because \(-5\) is the opposite of \(5\), this implies that \(-5(-3)=15\).

If two numbers with the same sign are multiplied, the product is positive.

WARNING! These rules are different from the rules for addition; be careful not to mix them up.

Find each product.

- \(-2(-9)\)

- \(-3(-7)\)

Recall that an exponent represents a repeated multiplication. Let’s see what happens when we raise a negative number to an exponent.

Evaluate each expression.

- \((-2)^2\)

- \((-2)^3\)

- \((-2)^4\)

- \((-2)^5\)

If a negative number is raised to an even power, the result is positive.

If a negative number is raised to an odd power, the result is negative.

Dividing Negative Numbers

Let’s go back to the coffee example we saw earlier: \(-3\cdot5=-15\). We can rewrite this fact using division and see that \(-15\div5=-3\); a negative divided by a positive gives a negative result. Also, \(-15\div-3=5\); a negative divided by a negative gives a positive result. This means that the rules for division work exactly like the rules for multiplication.

If two numbers with opposite signs are divided, the quotient is negative.

If two numbers with the same sign are divided, the quotient is positive.

Find each quotient.

- \(–42\div6\)

- \(32\div(–8)\)

- \(–27\div(–3)\)

- \(0\div4\)

- \(0\div(–4)\)

- \(4\div0\)

Go ahead and check those last three exercises with a calculator. Any surprises?

0 divided by another number is 0.

A number divided by 0 is undefined, or not a real number.

Here’s a quick explanation of why \(4\div0\) can’t be a real number. Suppose that there is a mystery number, which we’ll call \(n\), such that \(4\div0=n\). Then we can rewrite this division as a related multiplication, \(n\cdot0=4\). But because \(0\) times any number is \(0\), the left side of this equation is \(0\), and we get the result that \(0=4\), which doesn’t make sense. Therefore, there is no such number \(n\), and \(4\div0\) cannot be a real number.

Order of Operations with Negative Numbers

P: Work inside of parentheses or grouping symbols, following the order PEMDAS as necessary.

E: Evaluate exponents.

MD: Perform multiplications and divisions from left to right.

AS: Perform additions and subtractions from left to right.

Evaluate each expression using the order of operations.

- \((2–5)^2\cdot2+1\)

- \(2–5^2\cdot(2+1)\)

- \([7(–2)+16]\div2\)

- \(7(–2)+16\div2\)

- \(\dfrac{1-3^4}{2(5)}\)

- \(\dfrac{(1-3)^4}{2}\cdot5\)