1.1: Examples

- Page ID

- 2128

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Example 1.1.1:

\(u_y=0\), where \(u=u(x,y)\). All functions \(u=w(x)\) are solutions.

Example 1.1.2:

\(u_x=u_y\), where \(u=u(x,y)\). A change of coordinates transforms this equation into an equation of the first example. Set \(\xi=x+y,\ \eta=x-y\), then

$$

u(x,y)=u\left(\frac{\xi+\eta}{2},\frac{\xi-\eta}{2}\right)=:v(\xi,\eta).

$$

Assume \(u\in C^1\), then

$$

v_\eta=\frac{1}{2}(u_x-u_y).

$$

If \(u_x=u_y\), then \(v_\eta=0\) and vice versa, thus \(v=w(\xi)\) are solutions for arbitrary \(C^1\)-functions \(w(\xi)\). Consequently, we have a large class of solutions of the original partial differential equation: \(u=w(x+y)\) with an arbitrary \(C^1\)-function \(w\).

Example 1.1.3:

A necessary and sufficient condition such that for given \(C^1\)-functions \(M,\ N\) the integral

$$

\int_{P_0}^{P_1}\ M(x,y)dx+N(x,y)dy

$$

is independent of the curve which connects the points \(P_0\) with \(P_1\) in a simply connected domain \(\Omega\subset\mathbb{R}^2\) is that the partial differential equation (condition of integrability)

$$

M_y=N_x

$$

in \(\Omega\).

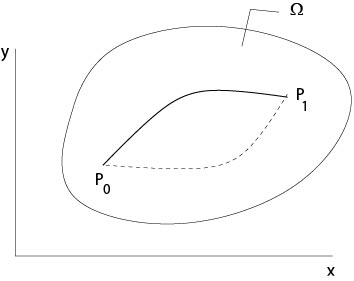

Figure 1.1.1: Independence of the path

This is one equation for two functions. A large class of solutions is given by \(M=\Phi_x,\ N=\Phi_y\), where \(\Phi(x,y)\) is an arbitrary \(C^2\)-function. It follows from Gauss theorem that these are all \(C^1\)-solutions of the above differential equation.

Example 1.1.4: Method of an integrating multiplier for an ordinary

differential

equation

Consider the ordinary differential equation

$$

M(x,y)dx+N(x,y)dy=0

$$

for given \(C^1\)-functions \(M,\ N\). Then we seek a \(C^1\)-function \(\mu(x,y)\) such that \(\mu Mdx+\mu Ndy\) is a total differential, i. e., that \((\mu M)_y=(\mu N)_x\) is satisfied. This is a linear partial differential equation of first order for \(\mu\):

$$

M\mu_y-N\mu_x=\mu (N_x-M_y).

\]

Example 1.1.5:

Two \(C^1\)-functions \(u(x,y)\) and \(v(x,y)\) are said to be functionally dependent if

$$

\det\left(\begin{array}{cc}u_x&u_y\\v_x&v_y\end{array}\right)=0,

$$

which is a linear partial differential equation of first order for \(u\) if \(v\) is a given \(C^1\)-function. A large class of solutions is given by

$$

u=H(v(x,y)),

$$

where \(H\) is an arbitrary \(C^1\)-function.

Example 1.1.6: Cauchy-Riemann equations

Set \(f(z)=u(x,y)+iv(x,y)\), where \(z=x+iy\) and \(u,\ v\) are given \(C^1(\Omega)\)-functions. Here \(\Omega\) is a domain in \(\mathbb{R}^2\). If the function \(f(z)\) is differentiable with respect to the complex variable \(z\) then \(u,\ v\) satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations

$$

u_x=v_y,\ \ u_y=-v_x.

$$

It is known from the theory of functions of one complex variable that the real part \(u\) and the imaginary part \(v\) of a differentiable function \(f(z)\) are solutions of the Laplace equation

$$

\triangle u=0,\ \ \triangle v=0,

$$

where \(\triangle u= u_{xx}+u_{yy}\).

Example 1.1.7: Newton Potential

The Newton potential

$$

u=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}}

$$

is a solution of the Laplace equation in \(\mathbb{R}^3\setminus{(0,0,0)}\), that is, of

$$

u_{xx}+u_{yy}+u_{zz}=0.

\]

Example 1.1.8: Heat equation

Let \(u(x,t)\) be the temperature of a point \(x\in\Omega\) at time \(t\), where \(\Omega\subset\mathbb{R}^3\) is a domain. Then \(u(x,t)\) satisfies in \(\Omega\times[0,\infty)\) the heat equation

$$

u_t=k\triangle u,

$$

where \(\triangle u= u_{x_1x_1}+u_{x_2x_2}+u_{x_3x_3}\) and \(k\) is a positive constant. The condition

$$

u(x,0)=u_0(x),\ \ x\in \Omega,

$$

where \(u_0(x)\) is given, is an initial condition associated to the above heat equation. The condition

$$

u(x,t)=h(x,t),\ \ x\in \partial\Omega,\ t\ge0,

$$

where \(h(x,t)\) is given, is a boundary condition for the heat equation.

If \(h(x,t)=g(x)\), that is, \(h\) is independent of \(t\), then one expects that the solution \(u(x,t)\) tends to a function \(v(x)\) if \(t\to\infty\). Moreover, it turns out that \(v\) is the solution of the boundary value problem for the Laplace equation

\begin{eqnarray*}

\triangle v&=&0\ \ \mbox{in}\ \Omega\\

v&=&g(x)\ \ \mbox{on}\ \partial\Omega.

\end{eqnarray*}

Example 1.1.9: Wave equation

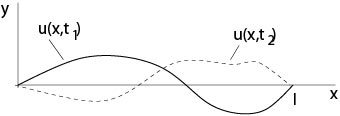

Figure 1.1.2: Oscillating string

The wave equation

$$

u_{tt}=c^2\triangle u,

$$

where \(u=u(x,t)\), \(c\) is a positive constant, describes oscillations of membranes or of three dimensional domains, for example. In the one-dimensional case

$$

u_{tt}=c^2 u_{xx}

$$

describes oscillations of a string.

Associated initial conditions are

$$

u(x,0)=u_0(x),\ \ u_t(x,0)=u_1(x),

$$

where \(u_0,\ u_1\) are given functions. Thus the initial position and the initial velocity are prescribed.

If the string is finite one describes additionally boundary conditions, for example

$$

u(0,t)=0,\ \ u(l,t)=0\ \ \mbox{for all}\ t\ge 0.

\]

Contributors and Attributions

Integrated by Justin Marshall.